Note: This essay was originally published to my Tiny Barber, Post Office pop-up newsletter in December 2021, towards the end of my ten-city walking tour. I often think of Den, and frequently want to link to the story of Den. The full archive of TBPO is available to SPECIAL PROJECTS members (and it is those same members and memberships that enabled the walk and this essay itself), but I wanted to pull this one entry out, make it public, give a home on the wider web. So here it is — edited and updated with more photos and links.

Hello, Den

Den Ōkōchi loves to have his photo taken. I say, Den, mind if I take a few? and up he jumps yelling, hold on a sec, as he runs into his room and puts on his signature tangzhuang shirt — a boxy button-down of dark linen, flat-hemmed, straight collar, very Chinese. What do you call those in Japanese? I ask, those shirts I’ve always seen Den in when he’s performing his duty as kaicho of the inn. He laughs and says, You know … I don’t know!

Den poses for me but Den has always posed well. If you look through his many, many albums of photographs covering some of the previous seventy years, there he is: Often in a skinny dark suit, dark tie, hair pomade’d back slick, sometimes serious, sometimes a toothy smile, always the same floppy ears sticking out. You can’t miss Den in a group. He radiates Den. There he is at the lip of the Grand Canyon. Now at Harvard. Now around St. Mark’s Place in the East Village. It’s 1968 and Den has concocted one of the craziest travel itineraries I’ve ever heard of, all the more miraculous considering the time, his finances, the vibrancy of his experience.

Post war, it was tough to get passports, to even get government permission go abroad. It wasn’t until the 1964 Olympics that the idea of a common Japanese person traveling for leisure outside of the country was fully realized. But before Den would travel, the itch to do so had to be seeded.

Den was born into the Yōyokaku Inn’s family, middle child of five boys and one girl, grew up around the town of Karatsu, on the Japan Sea coast off the northern edge of Kyushu. Born in 1934, Japan was then nearly seventy years past the Meiji Restoration — where it opened its borders to outsiders after some four hundred years of Edo-era solitude. So when Den popped out, the country was well-acquainted with the notion of a foreign tourist. One major vector: ex-pat Brits living in Shangahi looking to get away. Kyushu was an easy landing port. Stiff-lipped Brits would boat over to Nagasaki or Beppu or Karatsu where a smattering of low-slung hotels were ready for them — seaside things with porches to lounge on, many nestled right inside the great coastal pine grove down the road from the inn.

You could just run up to them, the Brits, Den tells me. Could blabber in English, practice that English being learned in middle school. How are you? I’m fine thank you. This is a pen. And you? Nobody’s family had much. Den’s family had chickens, so they brought eggs as presents. The Ōkōchi gaggle would come running up to some British shack and the Brits would yell, Oh here come the egg boys! That’s how many eggs they were distributing.

Den’s father was originally a Nagai. But he fell in love — “real” love as they say, not arranged love — with the only daughter of Yōyokaku, an Ōkōchi. They married. Since the daughter wasn’t “able” (being a woman) to take over the inn, and the Ōkōchis had no sons, Den’s dad was adopted into the family to keep the inn going, to keep the stronger blood (the more successful blood, the blood that “owned” the inn) explicitly named and flowing and recognized in offspring. When you hear about inns in Japan being run for twenty generations by “the same family,” this is usually the case — frequent adult adoption. Sometimes the blood is or isn’t broken. Eventually — usually — it is. In the end, who cares? Blood is so silly. Everyone so close anyway. Most neighbors in these towns are probably first cousins. Heck, you out there reading this are probably my fourth cousin. The obsession with blood and so-called purity is a weird old affectation brought forward to modern times. Any DNA that’s made it this far is, in a way, the best of the best. Regardless, this notion is critical to the story of Den, so here it is: love, a man marries a woman, and in doing so changes his name, becomes the head of an inn.

Tokyo

Den went to university in Tokyo. His oldest brother went to Todai. The second to Keio. And he was supposed to do the same but it took him three years of life as a rōnin — a student failing entrance exams — before he passed, and when he passed he got into Waseda. I also went to Waseda, which delights Den. He pulls out his old yearbooks, we talk about Takadanobaba, where he used to drink, places he used to frequent, walks he took. His dormitory was in Shoto, the toniest of tony neighborhoods in Tokyo — up on the hill behind the classical music kissa icon Meikyoku Lion (founded 1926; would have been there when Den was a student) and the sex-filled Dogenzaka of Shibuya.

Shoto: Home to politicians and prime ministers and all that jazz. Now, tony in Tokyo isn’t American Exuberance Tony — we’re not talking Bel Air mansions, seventeen bedroom, four swimming pools, a bowling alley, nothing like that. Demure, but well maintained single family homes. A beautiful little park. For some reason his dormitory was there, and so whenever he told anyone where he lived they would go, Oh, we got a Bocchan on our hands here — bocchan being a rich, spoiled brat, made famous by Natsume Sōseki’s novel of the same name. Den cracks up — You should have seen the place, he says. No bocchan could have ever lived there.

At Waseda he joined the kanko gakkai — the tourist society, a student club. They go on reconnaissance trips to understand how tourism is developing. They go to Hakone and someone tells Den to check out of Fujiya Hotel and report back. He goes. He goes and his mind is blown.

Fujiya Hotel

Fujiya is one of the first “western” style hotels in Japan. It was built, and then quickly burnt down, and was rebuilt largely as it stands today. Den crossed the Fujiya threshold the first time in 1955. A mixture of western and Meiji and Taisho Era architecture — western wood ornamentation and vaulted, expansive ceilings, but with a Japanese sense of proportion, some sliding doors, one of the first indoor swimming pools in Japan, finely considered details throughout.

Japan’s early twentieth century — a moment where the flood of new ideas and technologies from abroad was relentless, and the efforts of integration were — if not always successful — inspired, funky, exciting, charming — is a fascinating period for almost all aspects of culture: literature, art, food, fashion and, of course, architecture.

So Den passes through and sees all this — this foreign otherness in the building itself — but also sees the Americans. So many Americans. Mostly Americans. Hardly any Japanese at this hotel. It’s like going abroad. The Fujiya as international portal. Cultural holodeck. That was it, he had to work here. Done and done. He reported back to the kanko gakkai — amazements! bewitching! — and upon graduation applied to work at the Fujiya. (Well, actually, he first applied to work for Japan Airlines, to be “close to the metal” of travel, but he failed the interview.) So he and a buddy show up at the Fujiya, together. The interview lasted all of a minute and they said, Sure, you’re in, show up next week.

The Fujiya didn’t train, just threw you in the pit, Den tells me, chuckling. Six months working the bar, six months as a waiter, six months as a cleaner. To get to the front desk was a long road of lifting things — beds, sheets, irons, tumblers. Actually more strict than a ryokan, Den says. Up at five in the morning to start prepping for a seven or eight am open. The bar opened at 11am but you had to start scrubbing the bathroom by eight. Miss anything and you get chewed out. But, Den says to me, you know, I didn’t dislike this work at all!

Den doesn’t say it explicitly, but I believe this is where Den became Den — where Den stepped into the skin he has worn for the last sixty years. Where he began cultivation of the Den that is boisterous and generous and extroverted, unreserved, loquacious, open and curious to all. I mean, sure, these qualities were there in Den, were seeded as a child, but they flourished at the Fujiya in his interactions with the guests.

Working the bar he met and instantly befriended — as he’d go on to do for so many friendships over the rest of his life — Arthur Shane. Guy from Hawaii. Maybe you’ve heard of my son? Art says and runs back up to his room. He returns with a record — The Kingston Trio. Bob Shane is his son.

Months later, the Trio, en route to Australia, sponsored by Time Magazine, does a small tour of Japan. Den gets a call: Hey, my dad says you’re the man; take the next two weeks off, you’re coming with us. It’s Bob. Den drops everything and becomes the interpreter, guide, guru for these young yodeling folkboys as they make their way around the country. While doing this Den is able to reveal bits of Japan otherwise inaccessible to non-Japanese visitors. He bring them into restaurants they wouldn’t have gotten into. They stay at the Three Sisters Ryokan in Kyoto. Layer by layer, he unpeels the country for these clean cut kids singing about murder in Tennessee.

Back to Yōyokaku

Den thinks: What the hell am I doing at the Fujiya? We got an inn back in Karatsu. Maybe a little shoddy, sure, a little rough around the edges, could use scrub, but an inn none the less. Den saw Yōyokaku as a curated and controlled entryway for foreigners to come and experience “real” Japan at a time when doing so was still a somewhat wild notion, and, quite frankly, difficult. No “real” ryokan was foreigner-welcoming. Everyone assumed: Westerners can’t sleep on tatami, only want to eat piles of steak, are loud and stinky (not entirely untrue, of course). But Den had seen the inquisitiveness, had befriended folks, and saw — not to put a cold business angle on it, because I don’t think Den was thinking of it in this way, but it is there, was there — a tremendous business opportunity to offer something nowhere else offered: Authenticity.

Den’s mother had passed away when he was fifteen. His dad didn’t like running the inn. Den wrote a passionate letter to his dad: Lemme run Yōyokaku! And his dad was all like: Hell yeah, I can’t stand it. Get back here ASAP, little man.

Post-war, traditional inns didn’t have many guests. Japanese folks didn’t have the cash to burn. So they were mostly used for special events — weddings and fancy business dinners and things like that. And if post-war Japanese folks went anywhere, they wanted a “hotel,” not some fussy, old-world “ryokan.” Yuck. It’s around this time when a bunch of onsen-town-based ryokans began to flip their names, slap on “hotel,” raze the wood, pour some concrete.

But Den wasn’t concerned with any of this, didn’t want classic guests. To get customers Den — now in his late 20s — would head up to Hakata and scout bars where foreigners hung out. Mostly these were US Navy folk. You have to understand, though, they were post-war intelligence folks (and then later, many were based here for the Vietnam war), many stationed at Sasebo, near Nagasaki. A lot of intelligence folks. Strangely high proportion of Ivy League kids, still in school, partially paying for school with service. So, you know, more cultured than you might be imagining, than the stereotype might indicate. Not front-line grunts floating through the jungles on opium. Code breakers and ballistics specialists. Anyway, he’d go to these bars and say: Hey, you boys, I’ll let you all stay for free at my Authentic Japanese Inn, and if you like it, you promise to bring friends next time?

Oh, you should have seen them, Den says, laughing. All these boys, twenty of them, showed up terrified. Didn’t know what to do. Den doubles over: When we greeted them at the genkan they got on their knees and put their foreheads on the ground. Ha ha! All dressed in their best suits and ties. Ho ho! Ohhh, it was ridiculous. They had no idea what to do and wanted to make the best impression and not offend us. I shoved them all in rooms together, four or five to a room. They loved it. We cooked up a storm and I hired a band and some hostesses from town to come and entertain and pour drinks and these boys had never experienced anything like this before.

Den, the original guerrilla marketer, original “do the thing that doesn’t scale” product-market-fit finder. Word got out — there’s this beautiful old inn with a zany young owner who speaks English and is a marvel and will welcome you with open arms. Den lists for me (with no small dollop of well-earned pride) the ever-increasing grade of enlisted man — ensign, commander, admiral — that arrived in groups with their wives and families.

Eventually, word and reputation spread so wide that in 1962, a young, newly married Franklin Rosevelt III and his wife came to stay. They adored it, adored Den. Everyone adored Den. The inn was great but the aura of Den — the barely five-foot-tall conductor, orchestrating the enchantment of all guests — made it greater. The sempiternal vibe of Den is, and has always been: love, connection, inclusivity.

Back in 2015, when I first interviewed Den — glass of red wine in hand, having changed out of his work clothes into a well-worn corduroy jacket — when he was a spritely eighty-one, he said this about that moment in the country’s history: You can’t buy time with money. Meaning old inns were tearing themselves down and rebuilding with concrete. An inn like Yōyokaku had an unassailable, priceless asset: The history embedded in the very wood, the floors, the earthen walls, the cat urine stains (as Den mentions multiple times) and Den saw the value in that in a moment when others couldn’t shed the old fast enough.

So it went for years.

The Great United States Trip

The Olympics came and that notion of going abroad — really going and traveling and tasting whatever it was on the other side of the ocean — was seeded, and Den set to mind how to go on an adventure.

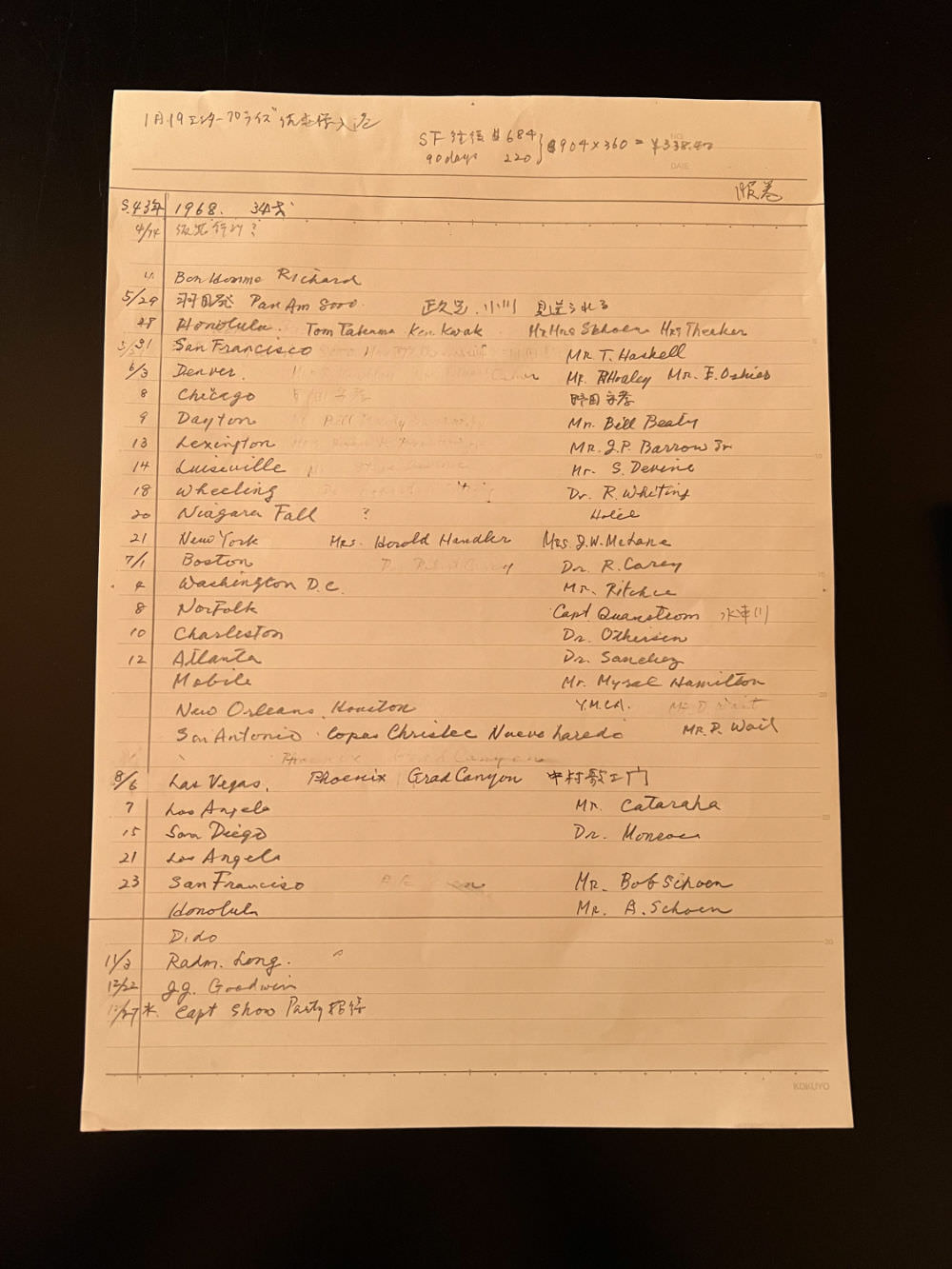

Problem was, he didn’t have any cash. His dad took all the inn’s earning. And didn’t pay him a salary. Finally, in 1968 he managed to finagle a bank loan for ¥500,000. Promised to pay it back ¥10,000 a month. Then, a United States Silver Dollar got you ¥360. So Den’s loan was $1,400, but in 2021 bucks: $11,000+. Den used $900 (2021: $7,500) on an open ended plane ticket he nabbed from JTB. And with $500 (2021: $4,100) in his pocket — the maximum amount you were allowed to take out of the country then (although, Den says, if you had friends abroad and were rich, there were ways to get money over there before you left) — off he went.

How long do you think I travelled for?, Den asks, his entire face twinkling with delight. Uh, two weeks? I say. Ha!, he says. One hundred days. Can you believe it?! I travelled on five bucks (forty in 2021 bucks) a day for a hundred days.

Den’s been working on something of a memoirs. He walks over to his desk and brings back the full itinerary — recently collated in neat handwriting from his copious travel notes, day by day, person by person — of that trip some sixty years back. Den travelled west to east and back again leaning on the hundreds of American customers he had befriended over the years. Called them just two days in advance: Hey! Den incoming! And if they were around, he’d arrive. Stayed with that famous Trio, dentists, upper-tier US Navy folk. He stayed with one guy with a prop plane who flew him to his next destination over midwestern fields bigger than Karatsu. He stayed in a YMCA in New Orleans and he made his way under those mega-sized Texas skies, across landscapes as wide as the whole of Japan.

Pure, scintillating love.

Back then, when you went abroad, before you left everyone gave you “senbetsu” — a farewell present — the implication being, you’d bring something back of much greater value from abroad. I asked Den what he brought and he said: Ponchos! Like, rain ponchos? No, like Mexican ponchos. He said he was able to buy them in bulk. Seventy cents a pop.

Back then planes couldn’t make it all the way from the west coast to Japan in one hop, so they all stopped in Hawai’i. Suited Den just fine. Prime mover Art Shane lived there. Suitcases full of ponchos, Den spent a few weeks eating pineapple, hanging out with his old buddy from the Fujiya.

Upon return, ponchos for all, he slid back to running the inn. Foreigners came, and a few Japanese came as well. But it wasn’t until pottery entered the picture that Yōyokaku entered the next phase of its life.

Pottery — Karatsu Yaki

Yōyokaku has had a long and close relationship with Nakazato Takashi, the famed potter. He grew up in Karatsu, twelfth generation potter under his father, Nakazato Muan, who was designated a living national treasure. Takashi is a bit of a strange cat, though, has shunned labels and titles his entire life. Largely recognized as one of the best living Japanese potters, he resolutely refuses anything like a living national treasure designation.

Den and Takashi had been friends since childhood. It was Takashi, who first traveled widely and wildly around the states in 1967. On return he inspired Den to finally get his act together and head out in ’68.

I don’t know much anything about pottery in Japan, but it seems that the general flow is something like: Eldest son follows in father’s footsteps, takes the father’s name, a name that has been passed down for generations, essentially “inhabits” the soul or manifestation of the father, carrying on the unbroken legacy of craft. If you aren’t the eldest son? You go indie.

Takashi wasn’t the eldest, so when Takashi went indie, he asked Den to be his manager, asked Yōyokaku to be his gallery.

I ask Den what was in the gallery space before he turned it into a Nakazato shrine and sales office? A ping pong table! he says, wistfully. Man, we loved ping pong.

Everything for me is luck, says Den. This friendship, the trust of Takashi is what put us on the map for Japanese visitors. Without his work and his commitment, I don’t know where the inn would be today.

Den doesn’t say it explicitly, but I suspect the financial boon of the pottery sales — of such an up and coming, and ultimately revered artist — may bring in more revenue than the work of the inn alone. Which is helpful, because sometimes a storm comes and blows the roofs off.

In 1990, or maybe 1991, a huge group of Germans was set to descend upon Yōyokaku. One problem: The biggest storm the area had seen in decades was heading straight for Karatsu.

Den called the head of the German group the morning of the day they were supposed to arrive. Guys, he said, this storm of all storms is heading our way. I’m so sorry but we can’t take you.

Turns out they had already checked out of their hotel in Fukuoka. Were about to get on the train to head down. Storm? the German leader said. We love storms! We’ve never seen a real Japanese storm! We want to watch it up close!

Oh, Germans.

So they came.

And so did the storm.

Pieces of roof began to fly off. Huge panes of glass fell in. Den shuffled the Germans from one once-safe room to another room, only for that next room to start leaking, for the windows to break. All night, this shuffle for life. In the morning, when the skies cleared and sun shone down on the shattered old inn, the Germans woke and greeted Den with huge smiles. Wunderbar! Amazing! they shouted. What an experience! Thank you, Den!

Den shakes his head, tells me, I couldn’t believe it. They loved it. Oh, Germans.

The Rebuild

Once again, luck, connections. Den’s cousin, Nagai Keiji is a famous chair collector. Go to the new Muji Hotel in Ginza and there’s a floor with chairs from his collection on it. Den pats a chair next to him in his home — a heavy looking modernist metal skeleton with a leather skin. How much do you think this costs? His cousin gave it to him. I have no idea. A small car, Den says, cackling.

It was this cousin he turned to in the early 90s, after the storm, when they had to rebuild the inn. Connected Den with the architect Schri Kakinuma (student of the famed Seiichi Shirai). They spent seven years rebuilding Yōyokaku with a menacing exactitude. I didn’t know the specifics of this history or the architect or of the storm when I first arrived. And yet here was my initial impression of the inn, written years back:

Over the years I’ve stayed in many ryokans. Why did this one impress? Because it was a faultless object. In so much as the experience of staying at an inn can be a singular, bounded thing. That is, the interface to the place itself — all of its surfaces — were, as far as I could tell, perfect. I couldn’t imagine better versions of them: The silken hardwood floors smoothed under a century of stockinged feet and slippers. The large glass panes, still original, mostly, and of that precisely imperfect turn-of-the-century cut, shimmering and making the garden do a watery dreamscape dance. And then the garden itself! The dozen matsu pines kept up, despite the high gardening costs. The proportions of the old rooms — visible wooden beams embedded into sunakabe earthen walls — creating that pleasing sense of thirds and fifths and golden ratios wherever you happen to look.

But all of that paled in the shadow of the locks and door knobs.

The irony of the Yōyokaku of today is that it is such a “flawless” gem in that it was essentially rebuilt in the early 90s. But you’d never know it. Den may have said, “Money can’t buy time,” but it can buy a helluva great carpenter, with exquisite sensibilities in wood selection, and an architect that is obsessed with shadow play.

And his cousin, the chair maniac, the design aficionado, told Den you’ve got one choice and only one choice of lock: Hori. Same as was used in the Okra Hotel at the time.

Here’s what I wrote about Hori locks:

Though they look beautiful, most of the awe of the user experience of the Hori lock is internal — the magic is in the feel of the mechanism. The keys themselves aren’t much special: They look like any old key. And yet, perchance they are lost, taken home by accident, dropped in a drain, eaten by a kite, their replacement requires considerable hand wringing and hemming and hawing as you can’t just cut a new copy but instead have to send Hori the serial number to have them forge a new one in their special furnaces. So, they are more unique than they seem at first blush. And then — then — you stick it in that pretty old lock and your life changes.

Even on my most recent trip, each time I locked and unlocked the door to my room: Abject delight.

The Hori key enters a Hori lock in such a way as to affirm your suspicion that every key you’ve ever inserted into every lock throughout your entire life was a sham. A false combination — jittery, sticky, imprecise. You realize how badly cut, forged by shoddy means, all the keys you own currently are. Using this Hori key and lock combination is similar to how you might have felt the first time you ever touched a masterfully finished piece of wood — shock at that glassy smoothness you didn’t think could be brought out from the material.

The key enters. Within perfectly milled chambers, the driver pins — attenuated by precisely tensioned springs — push against the key pins as the key slides forward in the keyway. The driver pins align to a dead-straight shear line and you feel the key settle with a satisfaction of a meticulously-measured thing spooning its Platonic opposite. Then you twist. The movement of the bolt away from the frame is so smooth — the door having been hung by some god of carpentry with the accuracy of a proton collision path — that you gasp, actually gasp, at the mechanism.

Through the luck of Takashi’s friendship, the luck of Takashi’s domestic and international recognition and pottery sales, the luck of jolly Germans (not dying) combined with the unexpected opportunity-luck of a storm, Den was gifted the chance to build back more refined than ever, but without ever letting on that anything was corrected. Yōyokaku feels as old and authentic a thing as you can imagine — and the bones and garden most certainly are — but all of it has been updated, refined, iterated upon. Knowing this makes it even more impressive of a place, and it’s tough not to look at Den as not a man of great luck, but a man who — through force of vibrancy and life — wills the movement of his universe in the direction of a greater-seeming luckiness. Excellent door knobs are just along for the ride.

Den shared most of this story with me in 2021, in his home, situated on the very grounds of the inn itself. From the living room, the single-story home — a hiraya — commands a panoramic view of the 450+ year old garden, the two main wings off the inn.

When I ask about the house, Den says, My philosophy was that the owner of the inn is not allowed to live in a place better than that in which the guests stay. But, he continues, then I retired.

He smirks, shrugs.

“Retirement”

The restrained structure he commissioned feels like sitting in silence and safety itself. The home, like an enlarged version of a small, perfectly milled wooden box made by a single master craftsman in a fabled mountain studio. Like a box you’d use to keep a single diamond, a cyanide capsule, a classic Rolex, a tampon, and an Oreo. A box of complete refinement, capable of elevating anything within it to some higher plane. It’s a home so well-hewn that multiple people have begged Den to introduce them to his carpenter, have fired architects they were currently mid-project working with to hire the Den crew.

His carpenter — the dude of the local dialect, “the” carpenter, who ended up driving me around with Den since Den was eager to show me so many of the local sights and can no longer drive — his carpenter walked me through the surprisingly varied woods in use in the living room alone: Straight teak floors, African teak for the bookshelves, a chestnut tree for the main beam. Consideration of tones and hue shifts. No knots in any of the supporting beams, grain all facing the same direction. It’s a set of details you’d never consciously notice, but once pointed out, you begin to feel the humming holistic harmony, and start to intuit that the absoluteness of these rooms is born from this detail obsession.

They take me into the back room, a tatami room. Look at the ceiling, they say. I look. I’m not sure what I’m looking for, and then I see it — Was this all cut from the same piece of wood? Yes, they say. Sliced, you could pile each board of the ceiling back onto each other and reconsistute the tree. Anyone who comes into this room, Den says, and points out the ceiling — I think to myself, Ah, a wealthy man. Only an idiot with money, he says, does things like this. And Den only did it because his carpenter was able to wiggle this out of his stockist on the cheap.

Over my days at the inn, Den and I ended up spending over ten hours together. Time expands and contracts with Den. You fly backwards and forward through a life — both in story and physicality. The inn, the neighborhood, the smattering of local shops are historic, and as you walk the streets with Den he points out this fading history, connects the dots. Of course, he is also stopped — Den! someone yells, Oh I’m so glad you’re doing OK. We can’t go anywhere without him being recognized. The carpenter drives us to the literal edge of the island and — in a tiny snail shack; that is, a place grilling up snails — a well-known politician walks past and says, Den? Den!

Leaving Yōyokaku is never an easy feat. I mean, emotionally. I am always sad to go.

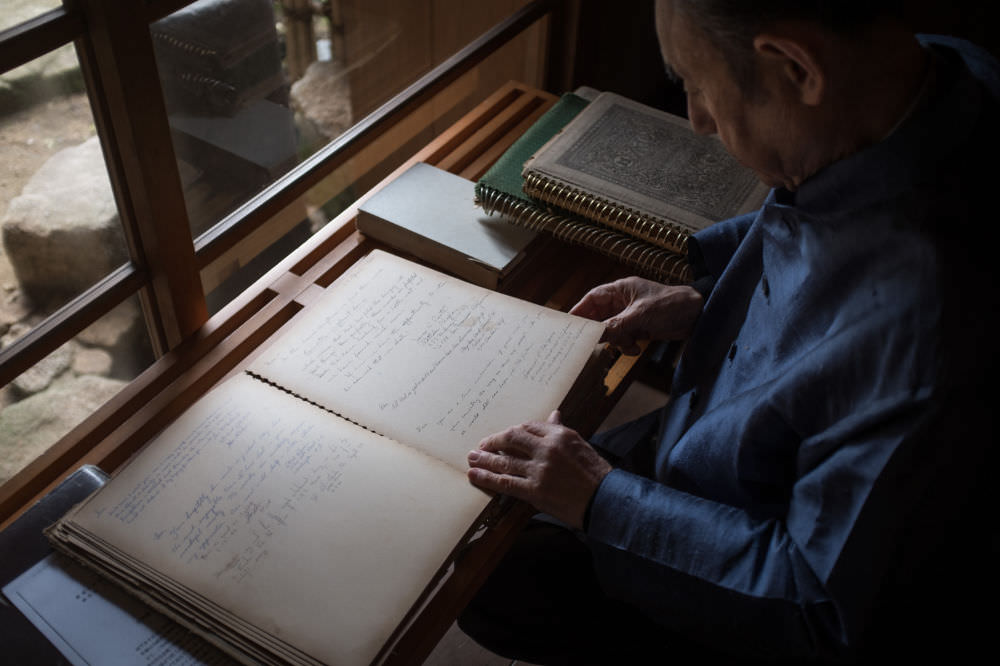

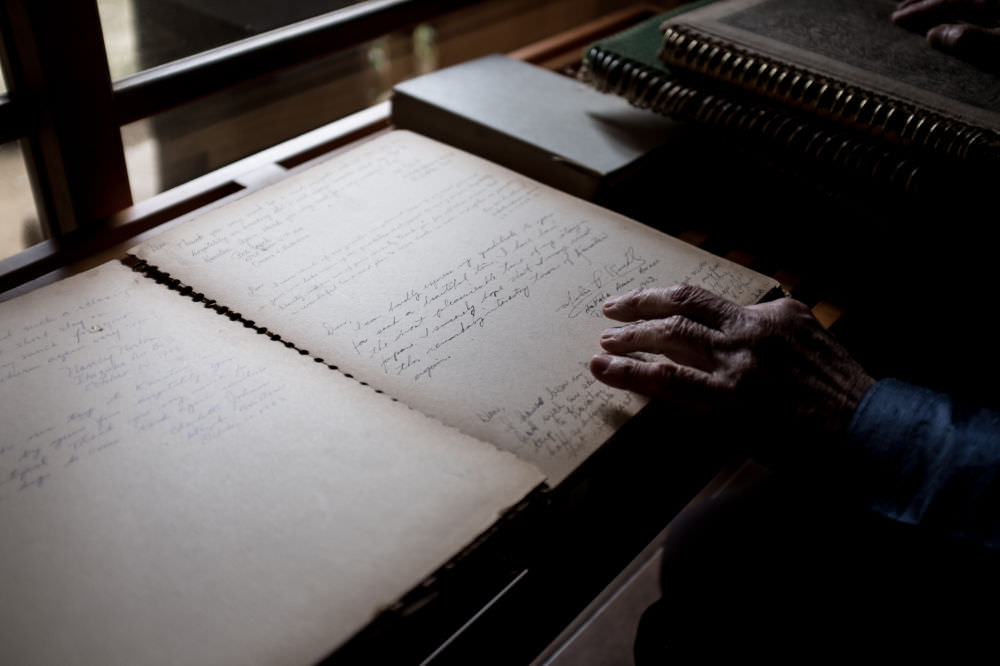

Back in 2015, when I first really sat with Den, he gestured for me to join him down a secret hallway. It was there he had stashed all of Yōyokaku’s logs. Dozens of fat, copper-ring-bound books. He laid them out, flipped through the pages. Not with a wistfulness, but a fullness. Here, on no uncertain terms was the legacy of his work, of bridging cultures, connecting folks, all rendered in elegant, swooping scripts: messages, notes, paeans to a place and man. “To the glorious days as we lived as you should live in Japan,” writes a Margret from Hawaii in blue pen on the thick guestbook paper. “Your hospitality and friendship have been unequaled in our travels. — May 15, 1964”

I’m often asked, Why walk? Why walk a country, chatting with folks, listening to their stories, taking their photos? Because you eventually land at Yōyokaku, and recognize — in a singular space — the piecemeal goodness of life that can be made visible and palpable through the medium of a walk. The walk becomes a platform, contains an activation energy, generates a richness often lost in the day-to-day.

Den Den Den All the Way Down

Den the man becomes Den the idea, reminds me not only of Den and Yōyokaku, but also so many others from along my Tiny Barber adventures: The fruit stand woman in Hakodate, the gentle barber in Morioka, the many, many coffee shop owners everywhere, the temple potter in Yamaguchi, the pizzaiolo and ramen masters in Matsumoto, the moms and their children in Onomichi, the world’s most popular tendon in Tsuruga, the sad son of the inventor of the Yuki Guni cocktail in Sakata, the owner of that bakery in Matsuyama. These people, their shops, the conversations we had are amplified by looking closely at someone like Den and what he built and how he built it.

Time spent in the orbit of a Den triggers a voice in the back of the mind: Ah, that’s what we felt along the road, elsewhere; some element of his universal inquisitiveness, his openness, his desire to bond. Amidst it all, a map for how to see and be seen with the very kindness Den himself holds — and has held — for his entire, inspiring life.

Take that map, shove it somewhere safe, somewhere close to the chest, and set off on your next walk.

But before you do, Den will pose, will always pose, for just one more shot.