Unbindings and Edges

Consider the magazine

On January 1, 2013, Newsweek goes unbound, but perhaps more interestingly, it becomes unbounded: Diffuse … Etherial … Digital!1

It’s worth taking a moment to meditate on this — the unbinding. It’s a phenomenon particular to our liminal stage in digital publishing. One in which we move from physical to digital. It hasn’t really happened before — there was no digital to move to.2 And, in a few years, it probably won’t happen very often, if ever — all publications will start with digital.

I wrote an op-ed over on CNN last week called, How magazines will be changed forever.3

The intent wasn’t to wax overly nostalgic,4 but instead to focus our attention on the one quality inherent to physical that I believe is underrepresented in digital: edges.

#Outer limits

The CNN piece begins:

Forget everything we know and love about physical magazines. Forget their length. Forget their size. Forget their weekly or monthly publishing schedule. Forget all these qualities except for one: What it’s like to come to an end, and to take a deep breath.

What does a bookend — an edge — mean for narrative arc? Broadly, it helps define the shape of the arc. The experience of a bundle of content changes depending on how it’s packaged.

Storify exemplifies this: By bookending a cohort of tweets, you remove them from the firehose and create a coherent, consumable narrative.

In other words: It’s difficult to shape a narrative without a pause, just as it’s hard to craft a beautiful page without whitespace. Possible, but unlikely.

Related: Is Gangnam Style as potent if it never resolves itself?

#Rigorous form

Nicholas Carr (The Shallows) posted a followup to my CNN piece on his blog. It begins:

One of the advantages of embedding culture in nature, of requiring that works of reason and imagination be given physical shape, is that it imposes on artists and thinkers the rigor of form, particularly the iron constraints of a beginning and an ending, and it gives to the rest of us the aesthetic, intellectual, and psychological satisfactions of having a rounded experience, of seeing the finish line in the distance, approaching it, arriving at it.

The ‘rigor of form’ is part and parcel of physical output, but it is something we have to work harder for in digital.

#Data

You can apply rigor of form beyond creative output — to all data.

Facebook, for example, works really hard to shave down your ~10,000+ daily newsfeed items to a high-signal:low-noise ratio stream. It tells an eminently consumable version of the story of your friends’ lives over the past day. And if you don’t like how the algorithm is working, Facebook offers users a host of manual levers to further increase signal. All of these levers and tunnels in the algorithm manifest as edges. And those edges make the unconsumable, consumable.

#Apps

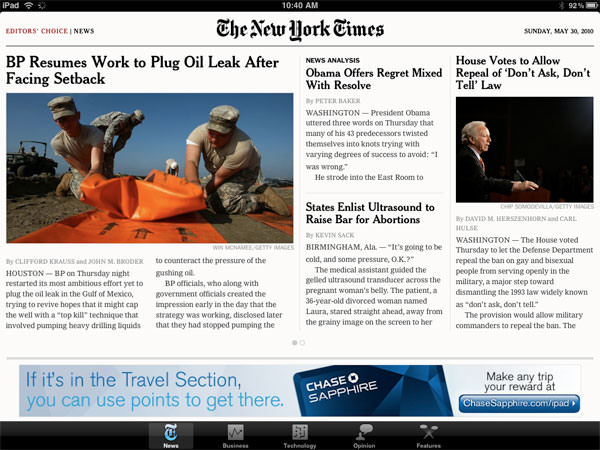

In 2010, the New York Times showcased an app during the iPad launch event. It was called “Editors Choice” and was available when iPad went on sale. Editors Choice was simple. Delightful, even. It contained just a few dozen articles. Selected daily by — one would assume — a cadre of Times editors. This limited selection made it feel handpicked. Filtered by a higher power that said, “This! This is all you need today!”

As you read each article, it turned grey. Once they were all grey, you were done. You could breathe.

#More

Ask us if we want more and we often say yes. More timeline. More newsfeed. More articles.

iOS star developer Loren Brichter (creator of the original OS X and iOS Twitter clients) is credited with inventing the now ubiquitous pull-to-refresh. In some ways it’s a near perfect gesture — attuned to our endless appetite.

We pull a lever. We get more [insert delicious content]. Pull pull pull. More more more.

The New York Times app has long since been replaced with its current version containing all of the newspaper. And while I understand the need for a completely inclusive reading space — especially across a news machine as big as The Times — I still admire the short lived — if, possibly, accidental — philosophical stand taken in Editor’s Choice.

There’s a reason Most Emailed and Top Ten article lists are so very popular: They’re one of the few bounded datasets on a newspaper home page. They’re high-signal lists, infrequently updated, that you know you can complete.

In the CNN piece I continue:

Linda Stone created the term “e-mail apnea” to describe holding your breath as you traverse the horrors of your inbox. I find myself experiencing digital apnea of all sorts. Google News apnea. Twitter apnea. Facebook newsfeed apnea. RSS reader apnea. In the face of endless content streams, it’s hard to stop and take a breath.

*pause*

There is no print apnea. Perhaps, at worst, one may experience library apnea – standing before the vast greatness of the reading room in the British Museum, for example. But even then, it’s different. There’s the cozy smell of old books and the softness of the aged pages. It’s more akin to basking in grandeur than to suffocating under information overload. It’s hard to feel the same reverence for our 24/7 Twitter feeds.

It’s easy for conversations around these topics to devolve into diatribes against information overload, self control, 32oz sodas, etc. Ignoring lurking moral quagmires, there’s certainly a time and place for the endless slurping of tweets. But, generally, I also think most of us would be grateful for less noise and more signal. For clearer narratives around amorphous data blobs.

Bringing the ethos of physical edges to digital spaces is all about increasing that signal.

Newsweek may soon be unbound, but just because it’s digital doesn’t mean it has to be unbounded.

-

A turn of the page for Newsweek, The Daily Beast ↩︎

-

There were variants of physical to physical, and arguably, intangible to tangible (spoken histories to written histories), but not tangible to intangible like this. ↩︎

-

I’ve also written extensively about jumping between digital and physical states on this website. It’s a long piece but approaches the subject from a more media agnostic place. ↩︎

-

If you read me regularly you know that I’m pro-digital with a strong humanist slant. Any implied nostalgia isn’t for a bygone era of things printed, but a rally to take a few moments, step back and make sure we cultivate an awareness of where we are. Sometimes slowing down means faster progress, and I’m all for progress. ↩︎