Walkers —

2021 chugs along and Ridgeline moves with it.

Our global un-travel situation has gotten me thinking a bit more about walks elsewhere, and how it’s logistically impossible for us to pull them off right now.

So I find myself drawn back to books I’ve used as travel proxies in the past — and McCarthy’s Blood Meridian is a book I’ve come back to many times over the years. It’s a bizarre book, a nasty book in many ways. But one thing it does with absolute certainty, using an arcane perversion of English, is take you places with a vividness few other books do.

The historical novel is set in the mid 1800s. Around 200 pages in, after all manner of Native American genocide and murder have been put on display, a chapter opens with this:

All to the north the rain had dragged black tendrils down from the thunderclouds like tracings of lampblack fallen in a beaker and in the night they could hear the drum of rain miles away on the prairie.

That tracings of lampblack fallen in a beaker really knocked me down the other day. A gorgeous observation. Who knows if the phenomenon is true, but it’s enough that one can imagine it and the image astounds.

That’s the trick with Blood Meridian — the book, for me, soars not on the shock factor of the gore, which is so gruesome it’s all you can see the first couple times through. The real singing value is in watching McCarthy contort himself and commit to spending roughly 100 of his 350 pages simply describing the rawness of the American southwest / northern Mexico. Over and over, another stretch of arid land, another night sky. The famous opening: “Night of your birth. Thirty-three. The Leonids they were called. God how did the stars fall. I looked for blackness, holes in the heavens. The Dippers stove.” That’s a helluva starry night.

The book is a spell, and the writer has self-ensorcelled in such a way to access this “tone” or “mode” of observing that is so far removed from the normal day-to-day that you sometimes feel drunk emerging from his universe.

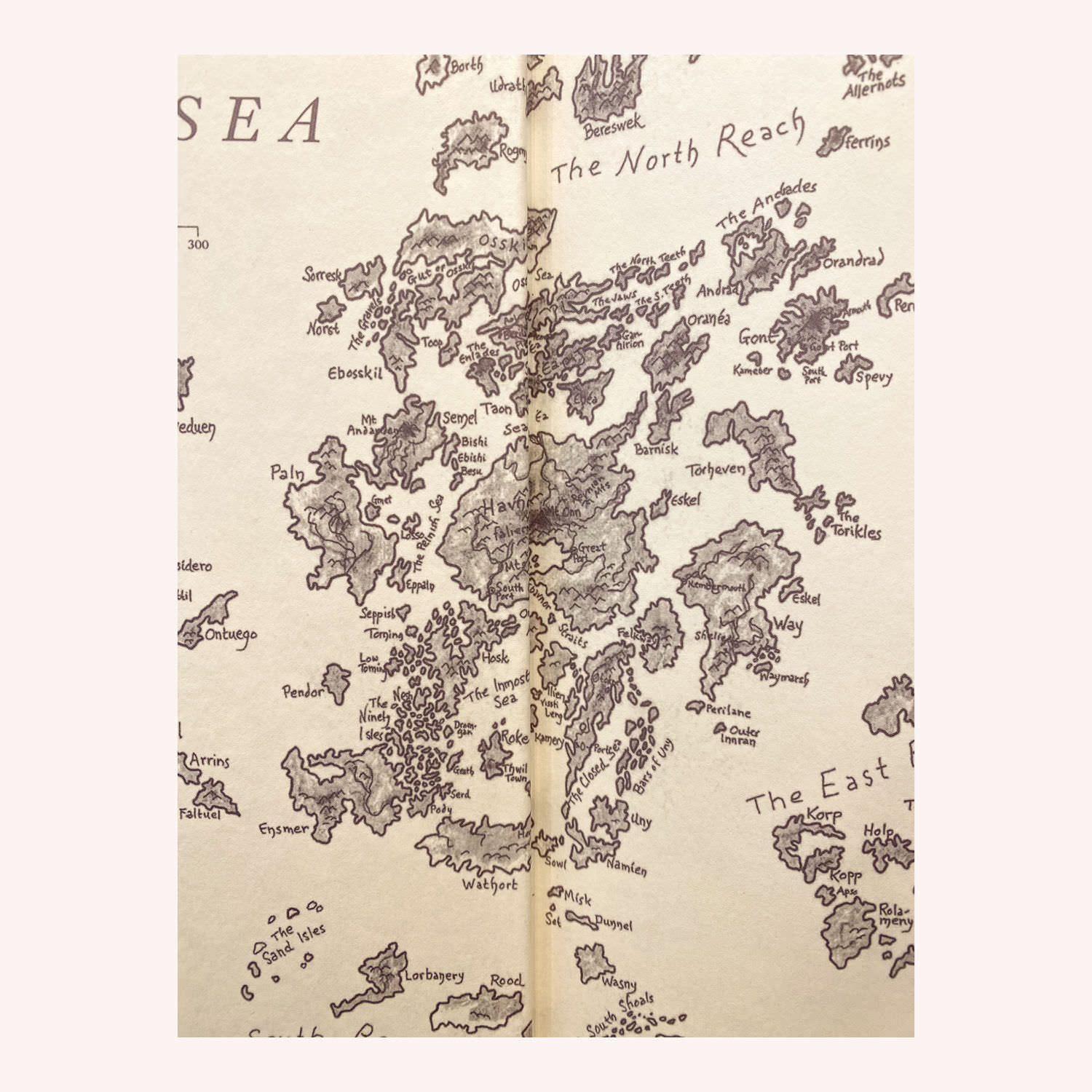

All of this brings to mind Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea. In some way a spiritual antipode to Blood Meridian — it’s a book of little violence, suffused with heart and the love of language and, darn it, the triumph of good. Le Guin even helps us understand the spell of McCarthy and his words:

The Hardic tongue of the Archipelago, though it has no more magic power in it than any other tongue of men, has its roots in the Old Speech, that language in which things are named with their true names: and the way to the understanding of this speech starts with the Runes that were written when the islands of the world first were raised up from the sea.

That’s what the McCarthy southwest feels like — the world being named with true names. It’s a trope that could so so so easily fall on its face (could so easily (and perhaps does?) induce endless eye-rolling) but because he’s so committed to the conjuring, so fully invested in the tone, it works. That total investment in a mode of working is — to me — what’s so impressive.

In The Snow Leopard (a non-fiction book of little violence and much observation), Matthiessen, having finally gotten to Shey and Crystal Mountain writes: “There is so much that enchants me in this spare, silent place that I move softly so as not to break a spell.”

“Moving softly” feels non-negotiable to access deep creativity, and yet I find it’s almost impossible to achieve while online. Even writing this, it happens to be 1:30am and I had been trying to sleep but then the Matthiessen line appeared, and it set my mind in motion. Ah, fine, OK, I’ll get up. But my mind was only receptive to it because I was quiet, was offline, in book mode, had laid the foundation earlier by drafting parts of this out, doing it all far from my phone or the network.

This tension between being swathed in the online world and going to a place with “true names” feels like one of the main contentions of anyone doing “deep work” today.

Hell, right now, I had to get out of bed and come downstairs and almost break my toe on a kettlebell to then lean over and type this out in a totally unergonomic posture. But this is how it works — you give yourself the sparseness, the space to be receptive to signals, signs, notes from the world that align with the work at hand, and then you choose to follow them or not.

This is, fundamentally, the role of so much of a long walk — space making, moving softly, passing the same objects over and over again, meeting the same people, and pulling from them all unique details worth remembering. Lampblack in a beaker, the true names of all the things, casting a spell of travel and place.

C

Fellow Walkers

Born and raised in the SF Bay Area, my family had a summer home up in the Sierras above Lake Tahoe. I spent the summers of my youth and adolescence, from the day school was out until the day it started back up, mostly unfettered, running, walking, swimming and sunning above 7000 feet of altitude. I made a solo backpacking trip from Yosemite to Tahoe when I was sixteen. In my late teens, I discovered bicycles. I raced bicycles for years and spent my career in the bicycle industry. It was not for another almost 40 years that I rediscovered walking. My partner and I walked the Camino de Santiago in 2017 and have been walking nearly every day since. We have walked in Spain, Portugal, Japan, Jordan, Ireland, Israel, the West Bank, sections of the Appalachian Trail and Pacific Crest Trail. Walking has been our stress reliever during these crazy times.

(“Fellow Walkers” are short bios of the other folks subscribed to this newsletter. In Ridgeline 001 I asked: “What shell were you torn from?” and got hundreds of responses. We’re working our way through them over the year. You’re an amazing, diverse crew. Grateful to be walking with you all. Feel free to send one in if you haven’t already.)