Well, hello Ridgeliners (there are SO MANY of you!) —

Good walks benefit from context. I figure if we’re going to be walking together for at least fifty-two weeks, it’s only polite and fair to introduce myself. Not the canned tuna boiler plate stuff on a bio page — that’s not what an honest walk is about.

I grew up in a small, uncommonly diverse, working class town in central Connecticut (I know — those words aren’t normally associated with the state, and in fact I didn’t know what words (yacht, pipe, hedge-fund, tweed, golden Maserati) were associated with Connecticut until I left). I’m adopted, don’t know my birth parents or the full split of my blood. The language of my youth was amazingly, spectacularly, breathtakingly, foul. I grew up saying shit and fuck and fucker and piss and crap. Crap this and crap that. And balls. And nut sack. As in: Hey, you nut sack! Inside the house my grandfather would lose his mind if anyone so much as uttered “fart.” Outside, all bets were off.

So: I grew up speaking like everyone around me (me, an unknown quantity, paired with a goofy cohort of first or second generation Italian and Polish and Laotian and Indian and Vietnamese and Puerto Rican immigrants), and everyone around me spoke like goddamned sailors (much to the chagrin of our mothers, but much aligned with our fathers).

I spent my entire eighth summer on this planet in a brutally serious spitting contest with my best friend, a kid named Bryan whose dad was famous for delivering the mail in shorts during snow storms. I can spit real good, lemme tell you. I can spit dozens of yards all day long.

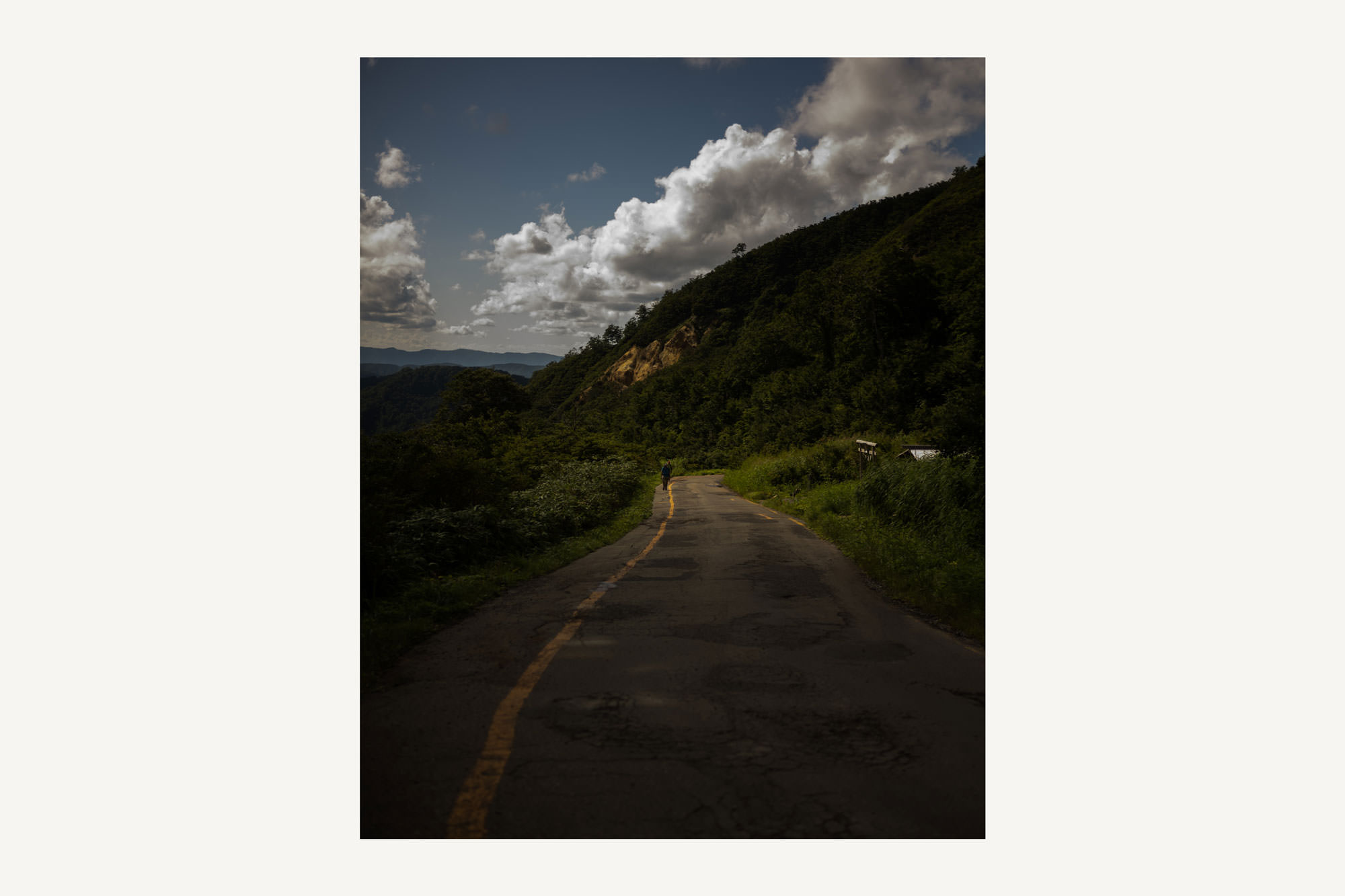

And so when I read the start of the 17th century poet Matsuo Basho’s Oku no Hoso Michi — his seminal chronicle of a 2,400 kilometer walk over 156 days hooking up into and through the northern Tohoku area of Japan — the feelings are manyfold:

The months and days are travelers of eternity. Just like the years that come and go. For those who live their lives on boats, or lead horses towards old age, their lives are travel, their journeys are home.

First, there’s the language. Which is so delicate and subtle and looping, indirect, lovely, considered, and in such stark contrast from the vulgar baseline of my childhood chatter that I feel a tightening in the chest (excitement! shock!) to even think about how distant these two places are. And then there’s the language of the mountains themselves. Which, also, can be brutal, but that brutality is never forced.

Second, I don’t know when it was I decided that my journey was home, but it must have been somewhere between spitting and swearing. It’s a philosophy so fundamental to how I’ve operated in life it almost feels established pre-consciousness.

This means if you find me writing in some affected register of pomposity here, I give you permission (implore you, really) to tap me on my shoulder and say: Hey, brother, no need for those airs.

I also share the above to emphasize the implicit solitude of walking — of movement through the world, away. That there exists a solitude or disconnect you can feel even in the presence of others. None of the folks I shared a childhood with ended up halfway across the world, traipsing around mountains, that’s for sure. Many simply vanished. Bryan was murdered soon after we graduated high school. There’s a lot to unpack about me being here in Japan, so very far away from all of that, but let’s just say the anomalous component of my presence looms large, is never far from thought. The mountains very much help me remember this.

Basho, finishes his impressive amble in Ogaki in 1689. He commemorated completion with the following haiku as he departed by boat for the newly rebuilt Ise Shrine. (I’ll devote an entire Ridgeline to Ise later, but 1689 marked, astonishingly, the 45th rebuilding of the shrine.)

Onwards to Futami (at Ise)

I am torn from you (like a clam torn from its shell)

and Autumn is departing too.

I can see all y’all, but you all can’t see each other. We’re walking together. I’d like to shine a light in your direction.

If you’re game, send me a line — what shell were you torn from? What made you who you were? Reply with a sentence you wouldn’t mind me sharing anonymously. I’ll append a few to the end of next week’s Ridgeline. Give us all a little more context about who we’re walking with.

Until then,

C