I just like the vibe of Kanazawa. Maybe it’s the general lack of tall buildings. Or the extreme walkability of it all — from the station to the main downtown area, to the gardens and tea districts. Maybe it’s the small streams that criss-cross the city, appearing alongside sinuous roads, burbling pleasantly, once useful for certain industries (pottery, indigo) now useful as a land value boost and a feature that makes this goofy walker smile. Maybe it’s the kindness of the folks, the freshness of the fish. Maybe it’s the ever-present spirit of D.T. Suzuki or Yoshiro Taniguchi.

It’s all of that. The vibe is simply on point. It’s a gem of a city that, until five years ago, didn’t have a Shinkansen stop. Now it does, now you can flit here from Tokyo in a couple hours. I am here. I’ve been here for the past six days. I go home today. That makes me a little sad.

It’s a weird time to be traveling anywhere in the world right now. Japan, too, certainly. But Japan, largely, has the pandemic “under control.” So the sense of a looming shadow beast isn’t quite ratcheted up to what it might be in, say, the US. Everyone here is largely smart, sensible, rational. There are a few unmasked dingdongs — usually young, loud, invincible (obviously) — but for the most part, everyone is doing the right thing and the corollary is that it doesn’t feel much like a risk to move around.

If you live in Japan, and are being safe, it seems like now would be the time to explore Japan. No tourists are allowed from abroad. Zero. Kanazawa city is empty. There are the locals, naturally, but nary a nose-in-smartphone roller of fake Rimowas. Which would be disconcerting if there wasn’t a sense that life will eventually return to normal. Who knows when (the second half of next year?), but it won’t be like this forever. And so now is the time to tour — to visit the gardens and temples and shrines and museums and eat at the tiny restaurants and kissas and do it all without the crush, the stress, the chaos of the tourist set in tow.

I’m presently writing from a little kissa called Higashi-de, next to the fish market, famous for its pudding which I’ve been told is “tough, not squishy” and a must-eat. I’m the only non-regular. The place is crazy with local chatter accented in a pleasingly incomprehensible way. A market worker barely cresting five-feet came in on his cell phone hollering about deliveries and then proceeded to greet everyone individually in the shop — mostly elderly women who are coffeeing it up after morning fish shopping. My pudding is forthcoming. The coffee is superb.

With government travel subsidies you can get a decent hotel room in Kanazawa for about ¥5000 ($50 USD) / night. I’ve been here for five nights. I’m tempted to stay longer!

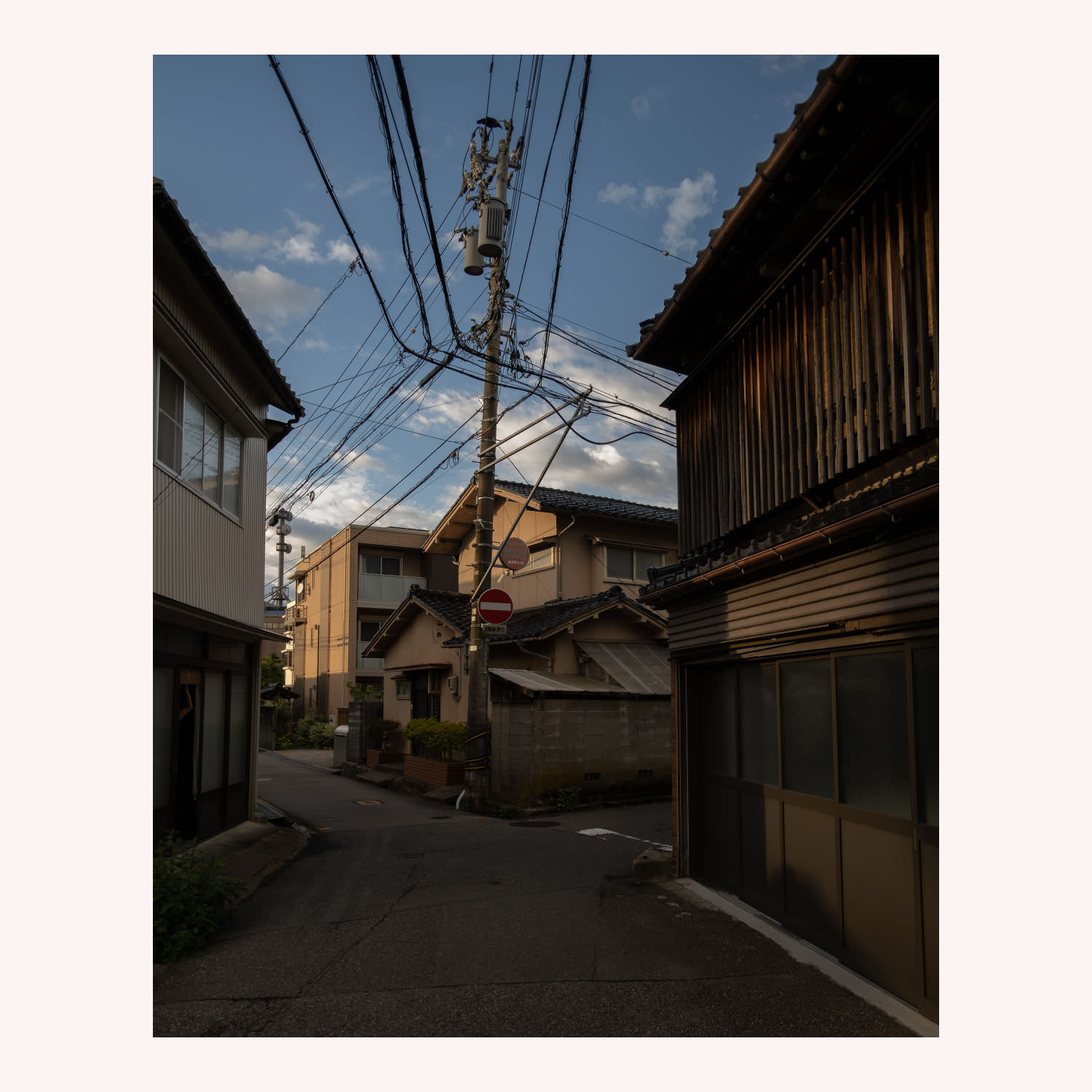

The heat has been unseasonably crushing, and the typhoons have threatened rain, so most of my walking has happened in the evening, around sunset. The sunsets have been beautiful; glancing golden light, holding for an hour or so before transitioning to a sky of pastels with big, typhoon-inspired cumulus cotton puffs. The streets of Kanazawa are narrow and circuitous, exactly as you’d expect of an old city that wasn’t devastated during the war. Kanazawa had no “heavy industry,” per se, and so was spared the fire bombs. So says Wikipedia. In a way, it’s a heartbreaking place to walk because you realize what Nagoya or parts of Tokyo might be like today. In Tokyo, you can see hints of the woulda-coulda-been in Yanaka or Sendagi, the bits that didn’t burn. But here, in Kanazawa, the majority of the city feels organic and untouched in a touching way.

Strangest of all is the collective “knowingness” shared among the obviously non-Japanese walking the streets. Until September we were essentially held captive by the government — were we to leave we wouldn’t have been let back into the country. Visa, marital, employment, tax status be damned. Didn’t matter if you owned a bank or a cafe. And so we nod with a tone that seems kinder. Weird times. Us foreigners here, still, at this moment know we aren’t quick transients, aren’t here for a week of sightseeing only to return to “real life” back in Europe or the US or South America or Thailand or wherever. This — however real or unreal it may be — is our life. Hotels don’t ask me for my passport (which they normally do, sometimes incessantly; you’re only required to show ID in Japan if you don’t have a Japanese address; a somewhat insane law, anyway, since it seems everyone should have to show ID by default), don’t ask me where I’m “from.” Nor do restaurants. The owners just chat. You’re brought quickly into the fold. It’s an eerie feeling. This past decade, Japan has been typified by a tourism crush unlike anything before, and with that has come a swelling blanket assumption (and exhaustion on the part of everyone) that if you don’t look like a Japanese-Asian then you’re to be treated immediately as a soon-to-be-gone outsider. I keep waiting for it to happen — the brittle, micro-othering — and … it doesn’t. It’s strange, somewhat idyllic. But then I remember that, in a way, this is how it was fifteen years ago when the world at large had yet to remember the wonder of Japan.

2020 is time-warp Japan, time-slip Japan.

On Friday night, a restaurant owner invited me to a zazen meditation session he was holding Sunday morning. That would have meant getting up at 5am. Not going to happen, not on this trip. I arrived in Kanazawa burnt out, had hit a few walls from overworking, had accumulated too much “poison” in my lymph nodes. “Your nodes are horrible,” a stout Chinese woman barked at me as she walked on my back. I was paying her to do so. She was mordant, applied her full weight with a chuckle. I sensed she enjoyed feeling my nodes transition from iron pellets to sponges. Me, some wimpy gweilo. I wondered how much a spine could take before breaking. I was sweating an astonishing amount. My pants were soaked. Was it urine? No, just sweat. I think. But why? From fear? I certainly feared the woman sauntering about my back, walking up and down the sides of my spinal column and then onto my gluteals, thighs, calves, and ankles. No, it was the nodes, the carried poisons, wasn’t it? They were releasing the sweat, the fears. When the backwalk was done, I felt emergent from something like a cocoon or deep-space hibernation. My vision was a blur. My partner and I walked the nearby castle grounds in a haze. They were struck by that evening light. The earlier rain had given way to a kind of mystical and somnambulant sky. Kanazawa was re-rendered in the Unreal Engine. Pre-release, we had slipped in. No one else was present. A private castle, perfectly lit. Looking inward: My body demanded fluids and ice cream. The humidity and heat produced a sensation of levitation. Levitating over the perfectly manicured grasses as produced by the simulation, back down into the town center, and to the shop that sold gold leafed ice cream. It cost about nine bucks. I would have paid a thousand. The gold leaf fluttered as if sentient. I approved of the algorithm. It knew of my newly clear nodes and my happiness for being able to explore this place in this moment. It knew of the vibe I dug and applied more of it through a trembling hypnosis. I was full-vibed, max-vibed. I watched the leaf dance, it revealed more secrets of the town, then I brought the vanilla ice cream and leaf together as one into my mouth and the soft sweetness and metallic tang of the gold mixed in a way that was as pleasing as I had hoped.

C

Fellow Walkers

Started walking in the misty, leech-infested mountains of Malaysia as relief from my authoritarian environs in Singapore. Recently settled in NYC for optimal city walking. A yearly long walk in alpine settings, preferably in Wyoming or Iceland, recharges me.

Walked mainly cities in France for years and years. Paris from one edge to the other, and around it along the Boulevards. It’s a fairly small city. Had a kid and stopped walking, more or less, for 15 years. Lost an eye. Healed, then bought new shoes and a backpack to walk again. In the Alps. Along the Atlantic. In the Cévennes, home of the Huguenots, R.L. Stevenson’s donkey, and, more recently, those French maoists who “went to the country” after 1968. It’s hard.

(“Fellow Walkers” are short bios of the other folks subscribed to this newsletter. In Ridgeline 001 I asked: “What shell were you torn from?” and got hundreds of responses. We’re working our way through them over the year. You’re an amazing, diverse crew. Grateful to be walking with you all. Feel free to send one in if you haven’t already.)