I figure I was peaking on some variant of high — runners high or completionist high or forest bathing high — for a solid three or four hours Sunday afternoon. I had entered that space of total “floating consciousness” I’ve written about before.

The body was just a machine. It was so obvious, so clear: the body, just a meat sack over which I had some third person point of view, from up and behind. There were a bunch of meters, gauges, off to the side — hydration, lactic acid, glucose, oxygenation, adenosine triphosphate, glycogen, creatine phosphate, generalized non-specific hunger, et cetera — that fluctuated, and in response to those fluctuations this third-person floating consciousness would just pour more water into the water hole, or shove peanuts into the chompy hole, or would tell the heavy-breathing sack to suckle some BCCA from a jelly packet. We had seven mountain passes to get over and were trying to get off the mountains by sunset, so although I hadn’t intended it to be a race, the day became a race of necessity.

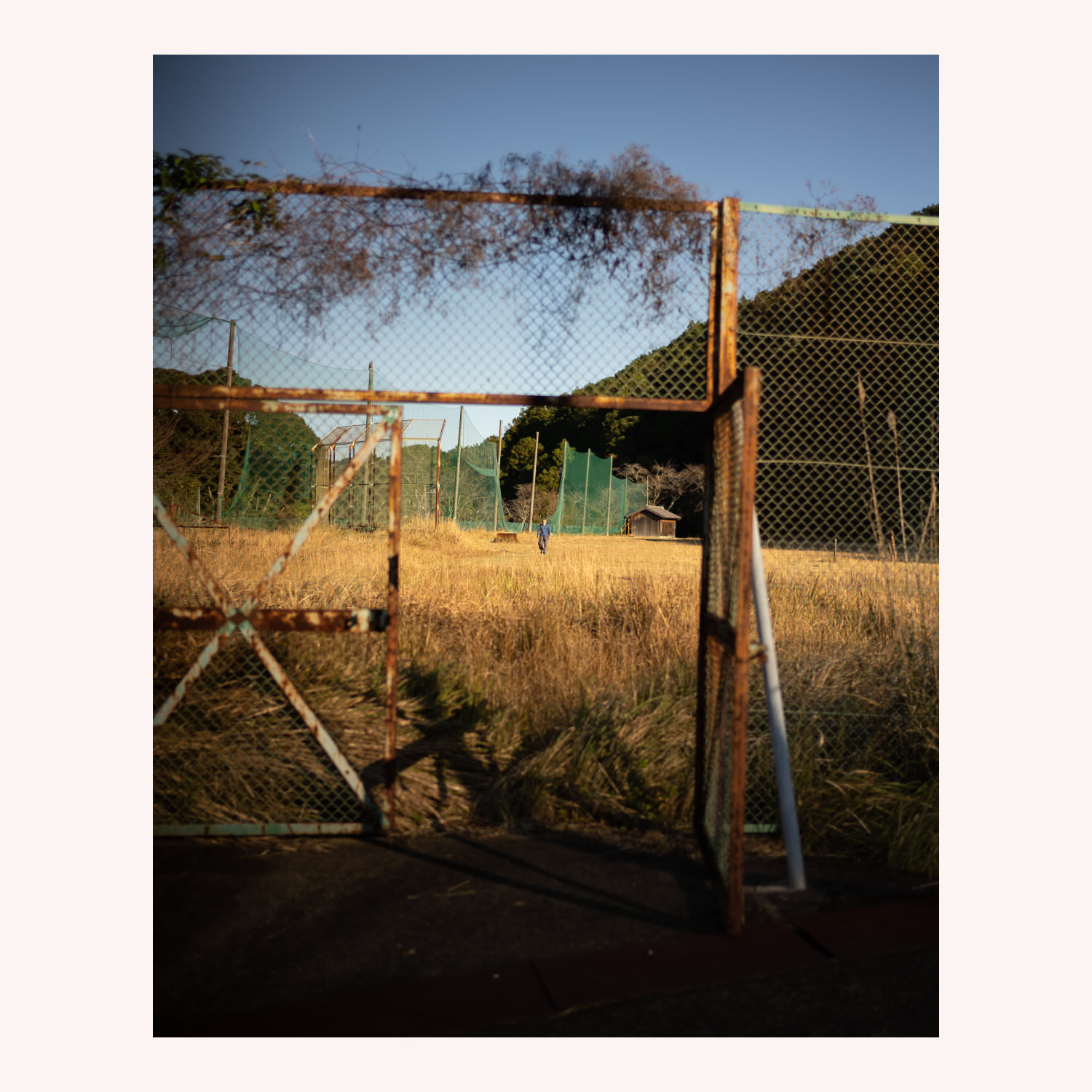

But that was fine. I had with me my Leki carbon hiking poles — which are marvels of engineering, beautifully designed — and found myself slipping into a zone that’s closer to trail runner than walker. Up and down the mountains, past abandoned baseball fields, overgrown with wheat, old men walking in circles. Through fishing villages, past long since shuttered cafes and hardware stores. I floated with a total and absolute lightness of being.

Even though I wasn’t “running,” my fastest kilometer was 00:07:00, almost double my usual walking speed (which seems to average out around 4.5km depending on how much I’m stopping to photograph or chat).

If you’ve never hiked with poles, you’d be amazed by how much they alleviate stress on the knees. Folks bandy around the number 30% — 30% less force on the legs. Who knows, but you feel the difference. Especially so when the mountains you’re climbing up and down are “paved” with Edo and Kamakura period slabs of stone. The kind of so-called paved paths which, when combined with the steepness of their eras, become paths that photograph beautifully (all mossy and glistening) and destroy the body beautifully as well (slippery as ice when just a little bit wet, every step a full-body-weight shock reflected straight back into the knees). And so the poles allow you to float — more floating — down the mountain. You enter into a hypnotic pole rhythm, where you aren’t so much walking anymore than swinging yourself down.

Throughout my entire seven days and 170km of walking, there was only one day, really, in which I saw other walkers: Sunday. And I flew past them, ladies and gents, young and old, lovers, loners, all folks who had set out to do one or two passes, were out for an easy forest stroll. I floated past them all like an orangutan ballerina, arboreal and oddly shaped, arms and poles as one, issuing “hello!”s and “good luck!”s and “sorry for going so quickly but I’ve got to beat the sun!” They gasped: Look at him go! (I think it may have even been a foreigner!)

In the middle of it, I had this strange notion that I could do this forever — this swinging down and pulling (which is what ascending with poles feels like) myself up mountains. There was no reason to stop, sunset be damned. To just keep going. The current meat machine my consciousness inhabited felt well-oiled, irrepressible, and unyielding to these puny mountains.

I think that impulse to go on forever, the feeling of the impossibility of growing tired, of having legs that would never give out, of being able to lift the 11kg pack on my back up another 300+ flights of stairs (which is what the day ended up at), was a proxy for gratitude, of being grateful for the health that authorized this weird gorilla dance, that permitted this day of walking and all the other days, too.

In the end the fuel ran out, the laws of physics could only be suspended for so long, the lactic acid won, and the last pass, saturnine, deep in shadow, though it wasn’t steep, kicked my ass. I arrived at the top still feeling high, but now extra grateful that I only had seven passes to crest, not eight. I made my way down into Kumano City — now stumbling more than floating — and headed straight for Mos Burger, where — having skipped any semblance of lunch or “food” the entire day — slowly devoured a few soy-patty burgers and enough french fries to kill a horse. Salt, it turned out, was the most divine of spices.

And so now, current status: Sitting on a northbound Nanki Express train sneaking peeks of my walk in reverse. Like a film being spooled up at a thousand frames per second, the train undoes the slow rhythm of the walk, replaces it with its own clack, and skips the passes all together — the mountains were dynamited to make this kind of quickness possible.

I’ll have more to say about the Ise-ji walk later, but overall: It was superb. And I’m trying to figure out how best to recommend it (courses, days, lodging) to folks looking for a few days along a historical, power-spot filled mountain walk in Japan. I’m hoping to add that writeup to walkkumano.com sometime in the next month or so. Work made possible by members of SPECIAL PROJECTS. Thank you for your support with these endeavors.

For now I’m greatly enjoying this ache in my thighs and arms, the residue from my intense push on Sunday. I have a final SW945 to upload — recorded during yesterday’s flat and plangent 25km along the sea — and my own bed to look forward to tonight. There’s just a few mountains between here and there. Easy.

Until next week,

C

Your weekly reminder: This newsletter is made possible by members of SPECIAL PROJECTS. If you’re enjoying it, consider joining. Thanks.

Fellow Walkers

“I have lived in San Francisco my entire life, so no matter where I am I walk in anticipation of hills and more right turns than left ones. I prefer walks that end where I started—walking from point A and ending at point B feels incomplete. Returning to beginning is a way of confirming the journey, but if I’m honest, it’s also a way avoiding the unknown. “

“I wasn’t so much torn from a shell as born from an arthritic one. And I is actually we - that’s me plus a 10 year-old German Wirehaired Pointer rescue called Flo. I walk to keep myself agile and healthy, to be at one with nature, and to feed my mind. She walks to follow her nose, to explore the world, and to get treats in the dog-friendly pubs. And together - and with my better half Doiks when we’re lucky (she’s a runner first and foremost) - you’ll find us in the English Lake District and the Scottish Highlands as much as possible and, daily, in south east England’s Surrey Hills.”

(“Fellow Walkers” are short bios of the other folks subscribed to this newsletter. In Ridgeline 001 I asked: “What shell were you torn from?” and got hundreds of responses. We’re working our way through them over the year. You’re an amazing, diverse crew. Grateful to be walking with you all. Feel free to send one in if you haven’t already.)