This past weekend (post workshop) I spent three days with a dear friend walking and hiking through Oze National Park. Since I had setup so many previous walks, he had set this one up. A kind of thank you walk. I had never heard of Oze, nor heard of anyone hiking there, so to me, everything was new and unexpected and a delight.

Oze itself opened officially as a national park in 2007, but folks have been hiking and carving trails out there for decades. It’s mainly marshland, plopped between Fukushima, Tochigi, Gunma, and Niigata Prefectures. It’s big, but not unknowable: 372 square kilometers. Given four days, an able body can walk the majority of the main trails.

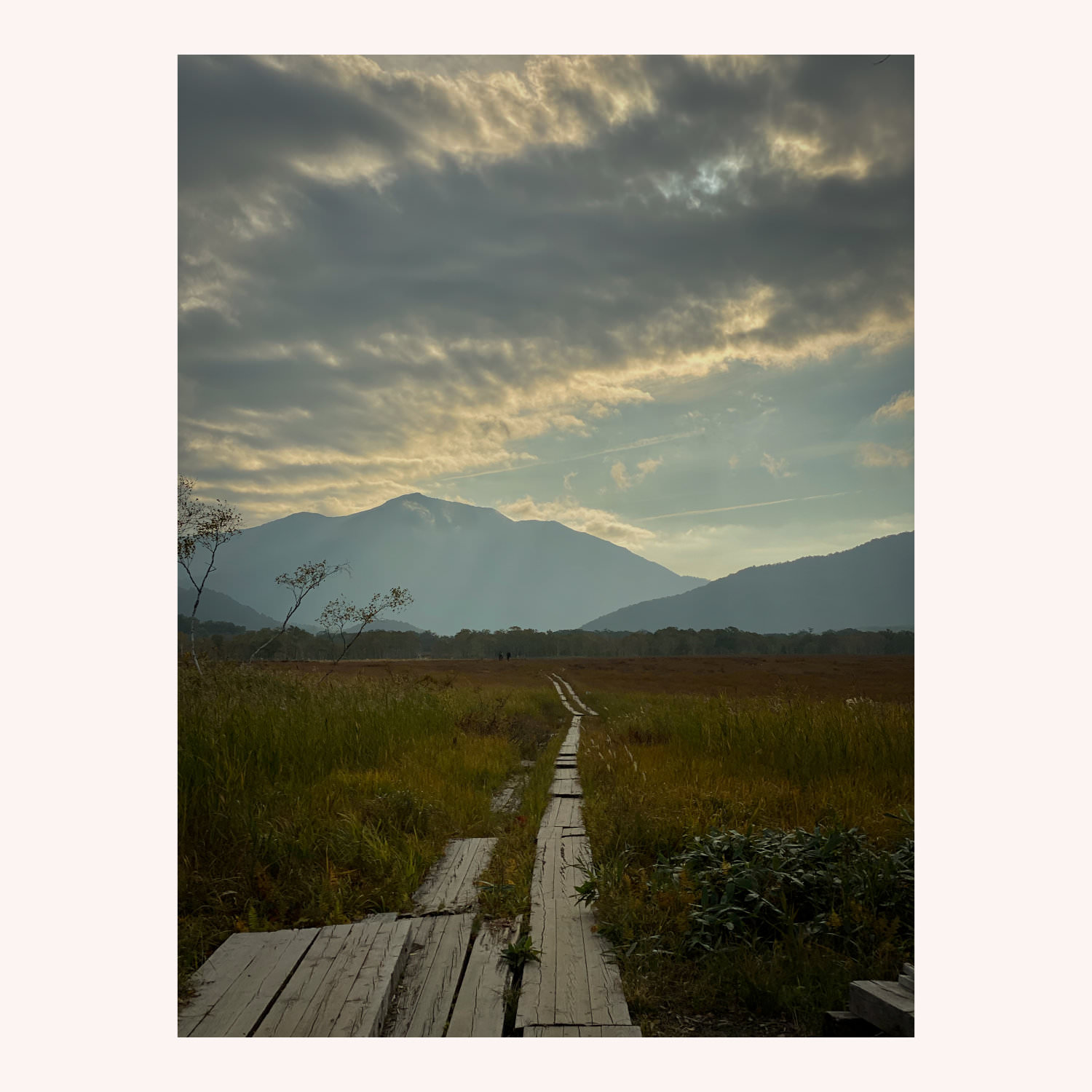

The park has branded itself visually via the wooden runners that cover most of its flat land — four- or five-plank thick runways elevated up off the swamp and grass. Sometimes in pairs, sometimes in single strips. Laid out in part to make the park navigable during the rainy season, and in part to protect the wildlife and keep walkers walking discreet corridors. Oze isn’t an exploratorium free-for-all — it’s more like a walking museum of nature.

One corollary of the planks is accessibility. Some ads for the park even show folks traversing the great open expanses in wheelchairs. Most of the planks are not wheelchair friendly, but they are old person friendly. And so the old people — clad in Mont Bell (Japan’s most well-known homegrown outdoor brand) from head to toe, gaiters, Vibram soles, UV-protecting hats, maximally Gore-Tex’d, walking poles and unnecessarily huge packs and bear bells tinkling — they come.

Walking Oze felt at times like walking the set of Cocoon; we were some of the youngest walkers and hikers by a generation+. We were but two of thousands of other visitors in the park over the weekend. I would estimate over 70% were over 70 years old.

Thanks to the network of mountain huts (yamagoya), spending a few days at Oze is a breeze. The huts offer private tatami rooms. The showers / baths don’t allow for soap or shampoo (environmental concerns), but they do allow for a rinsing off of the day’s sweat. For about ¥9000 you get dinner (5 p.m.) and breakfast (6 a.m.) and a couple of onigiri for lunch the next day. The second night, we were placed next to a room of women in their 80s, drunk as could be, chattering away like teenagers at a slumber party until lights out at 9 p.m. It felt like we had secretly snuck into a wilderness retirement home. It seemed like a fine place to die.

Lest you think the park is all planks and flatness, it is not. We climbed Hiuchigatake, 2,356m tall. Our ascent was roughly 1,200 meters. It was cold and raining and foggy the whole way up. Mostly it was muddy and rocky and rooty, but towards the top it shifted to boulder scrambles, nothing technical but still impressive to crest the peak and see a gaggle of twenty or so octogenarians sipping coffee in their Day-Glo waterproofs.

Signage around the park is a bit suspect, and we were gifted an extra 200m of re-ascent as we realized 40 minutes into our descent that we were heading off the mountain in the wrong direction. Back to the peak. We ended up chasing some 90-year-olds down the correct path, the sun burning off the fog just as we hit a lookout over the park’s main marsh.

If you can, try and spend two nights in at Oze. There are a few yamagoya that handle reservations in English. That said, the park seems criminally unknown to the tourist set: of the thousands of folks we saw, only four were non-Japanese. So it’s a good alternative to the crush of trails like the nakahechi on the Kumano Kodo.

You can get to Oze from Shinjuku via a single (very comfy) bus. Technically, you can do a day trip, but it’s much more sensible to walk Mount Takao or head to Kamakura for some trail walking if you are in Tokyo and only have a day.

Oze is replete with food and drinks — beer and Pocari Sweat and coffee and whiskey. You can even buy rain gear and shoes and walking poles. It’s a bit ridiculous, but also kind of sweet. Everything is helicoptered in, and therefore priced accordingly. One could show up in their underwear with a wad of cash and get fully outfitted and fed, ready for almost anything the park can throw at you.

Oze isn’t particularly historical, but it is well-stocked with plant life and is a nice polyculture antidote to the monoculture of many of Japan’s forests.

The walking season finishes this weekend. Soon Oze will be snowed in. Bookmark it for next year. It’s a great place to explore with kids or elders. Or as just a couple of doofs in their 30s, forgetting to check their GPS.

Until next week,

C

Your gentle weekly reminder: This newsletter is made possible by members of SPECIAL PROJECTS. If you’re enjoying it, consider joining. Thanks.

Fellow Walkers

“I spent eight, formative years as a child living inside Denali National Park in Alaska (back when it was still called Mt. McKinley). Walking was wandering through the wilderness. Even the outings we called hikes were mostly trail-less, passing first through the low, scraggly forests, then beating through thick brush into the higher, spongy tundra for expansive views and an urge to get to the next ridge, and to another high point, and on and on…”

“Raised in rural East England, only escaping to Scotland to attend Edinburgh University. Living in the north, maintaining an existence but not really living. Floated for such a long time that I no longer know what purpose is. Currently trying to reinvent and invigorate myself. Searching for new connections to deepen my experience. Always happy to hear from fellow beings.”

(“Fellow Walkers” are short bios of the other folks subscribed to this newsletter. In Ridgeline 001 I asked: “What shell were you torn from?” and got hundreds of responses. We’re working our way through them over the year. You’re an amazing, diverse crew. Grateful to be walking with you all. Feel free to send one in if you haven’t already.)