Postcards from the Baikonur Cosmodrome

A walk around the famous cosmodrome

Ridgeline Transmission 036

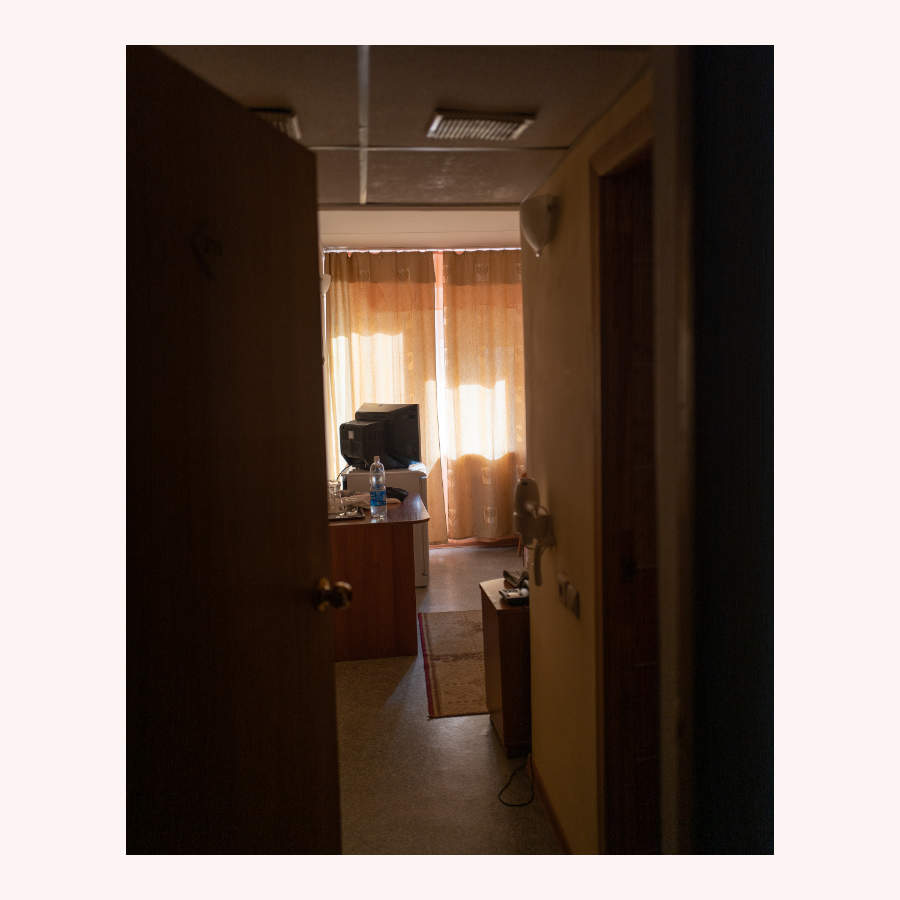

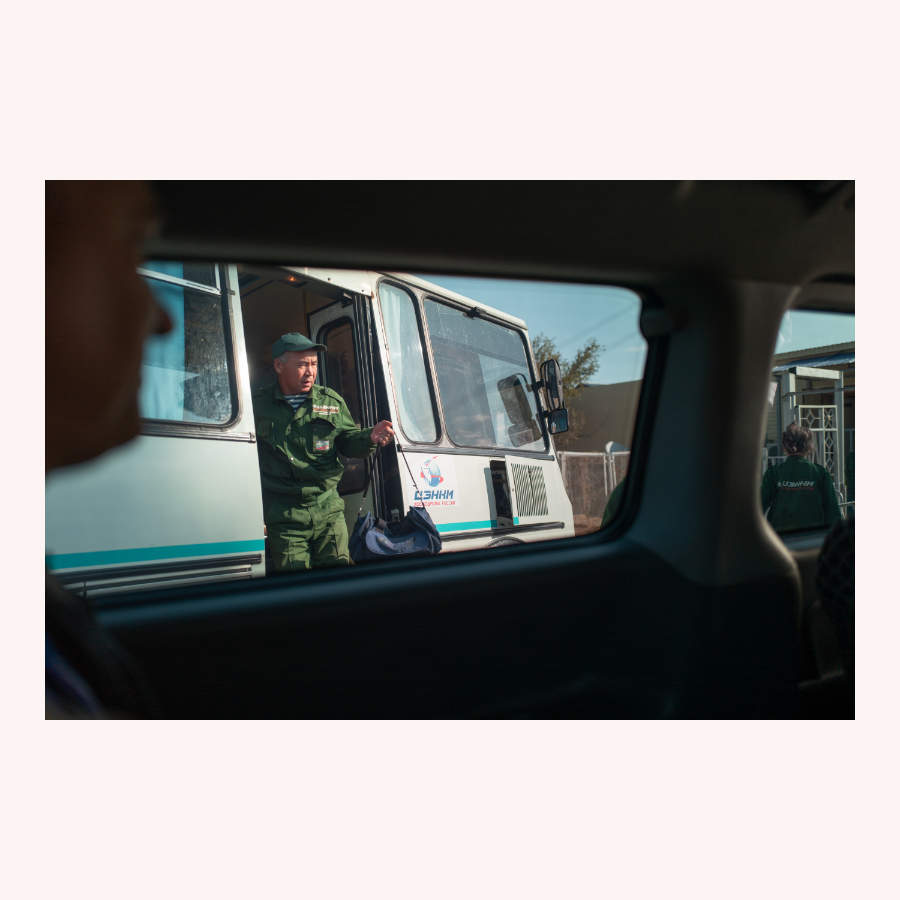

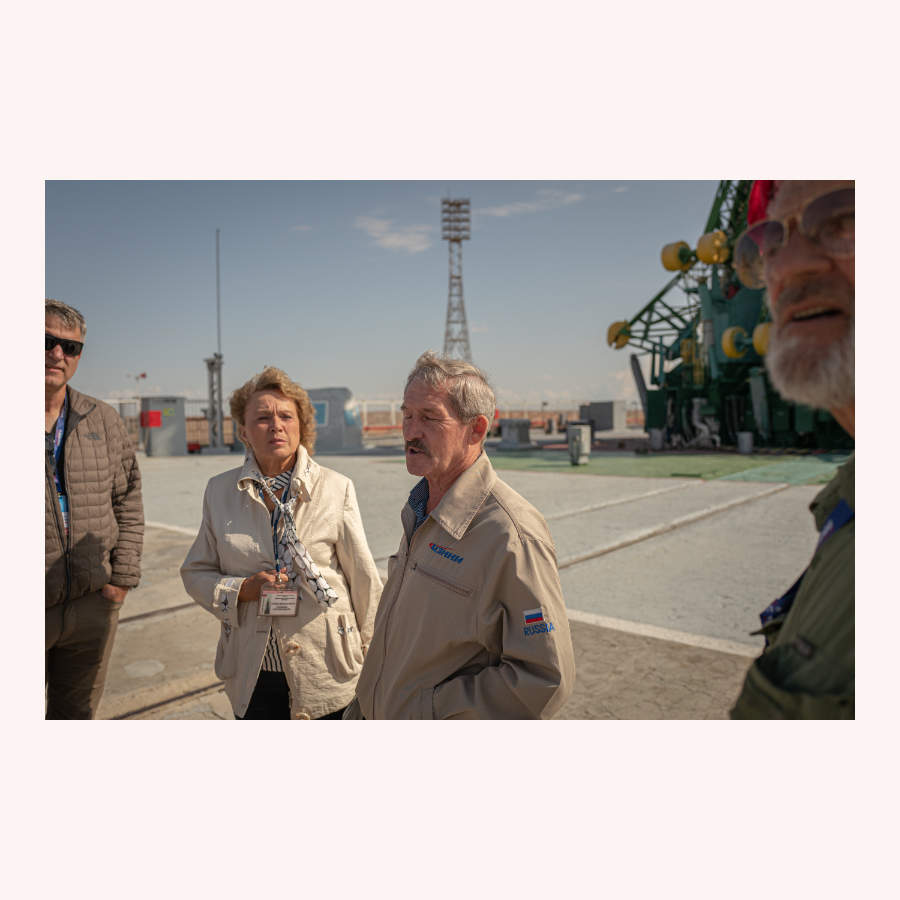

We had five or six handlers, or maybe three, or two, it was hard to keep track. The handlers, their roles, kept shifting — mostly white Russians in their fifties or sixties, tight perms, thin mustaches, some gaunt, other with thick bellies, strong handshakes, strange slip-ons shoes, stiletto heels. There were checkpoints. Seven? Eight? Guards with mirrors on the ends of long sticks. We were in Baikonur, the only place in the world capable of launching a human into space. We were staying on Lenin Square in a squat concrete hotel with stained glass windows and chandeliers and spartan rooms like single dormitories with towels embroidered with flowers.

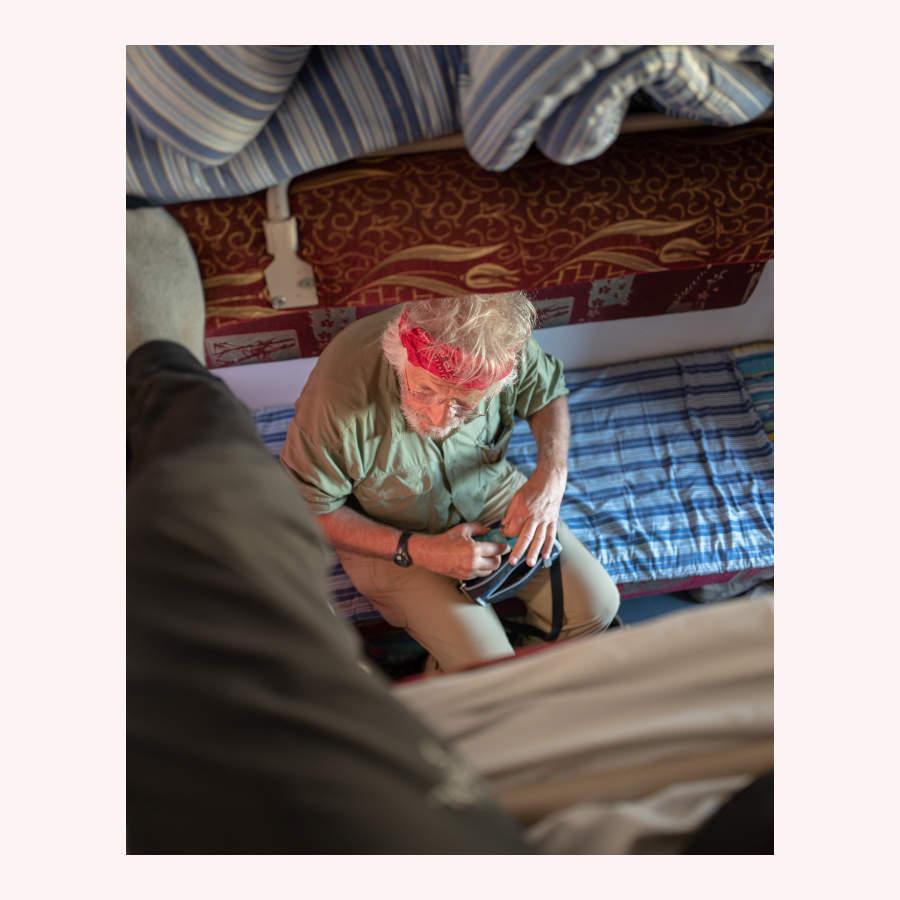

Machine translated forms were handed to us to sign. (“No smelly clothes.”) Our plans were unclear. To what did we have access? None of us knew. I certainly didn’t know. I am writing from a plane at this very moment en route to Astana, the bizarrely architectured capital of Qazaqstan, the last stop on a trip I joined only because of the people who were on it. I have three or four simple rules in life, one of which is to join (whenever possible) any trip with certain friends or colleagues. The destination is irrelevant. Walking will happen, walk-and-talks and long dinner conversations. The basic principle: Get close to good folks. Spend extended bouts of time together. Believe ever so slightly more in whatever it is that turns over their engines. Outside of the people and conversations, the glaciers, soviet spas and launch pads are just bonuses.

As for access, it turns out that we had lots of it. As one in our group put it: “The high value of low expectations.”

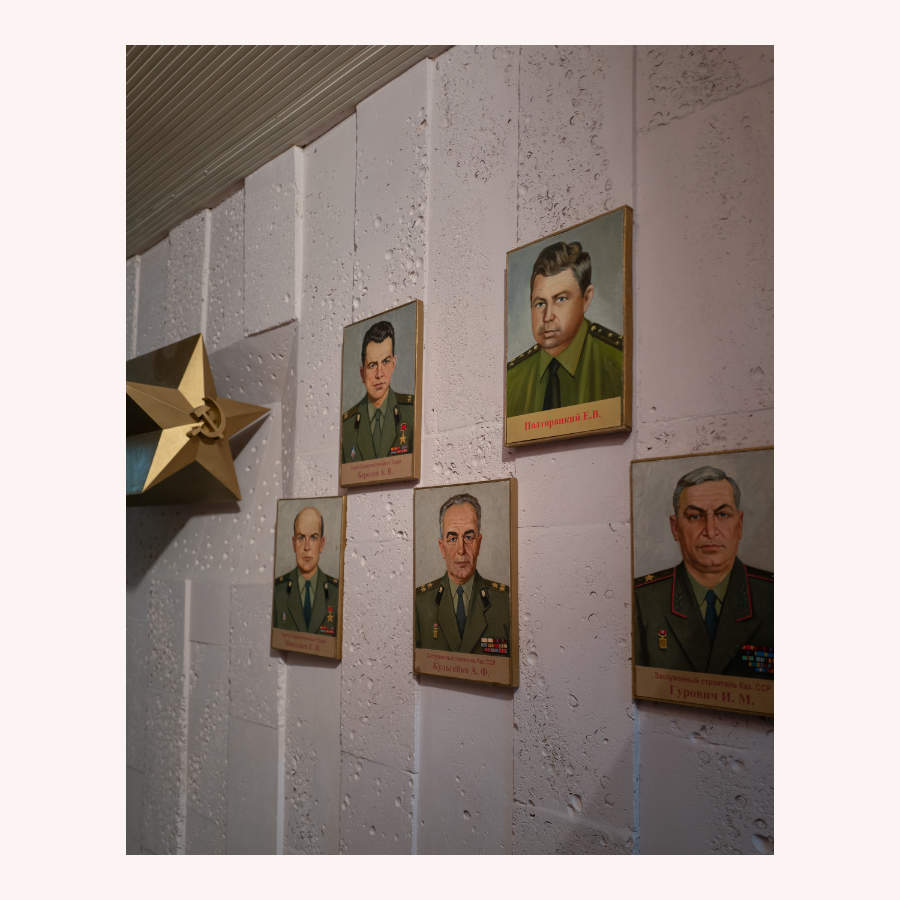

We arrived in Baikonur on a Sunday by way of an eight hour train journey. Everything was closed: Orthodox, you know the drill. But “they” (who? who knows!) opened the town museum for us, gave us an extended private tour, hammers and sickles, spacecraft, statecraft, etcetera. We walked the dusty city nearly bereft of life in the late-summer sun. One handler refused to leave our side. How many citizens live here?, we asked through Google Translate. 76,000 they said. Where were these citizens of Baikonur? Hiding? Weeds grew everywhere. Fat pipes carrying hot water crossed roads forming industrial archways. There were trees. Those trees did not look like they wanted to be in Baikonur. It was cool and dry, perfect strolling weather, although just a few weeks ago it was 51℃ and soon enough, minus nearly as much.

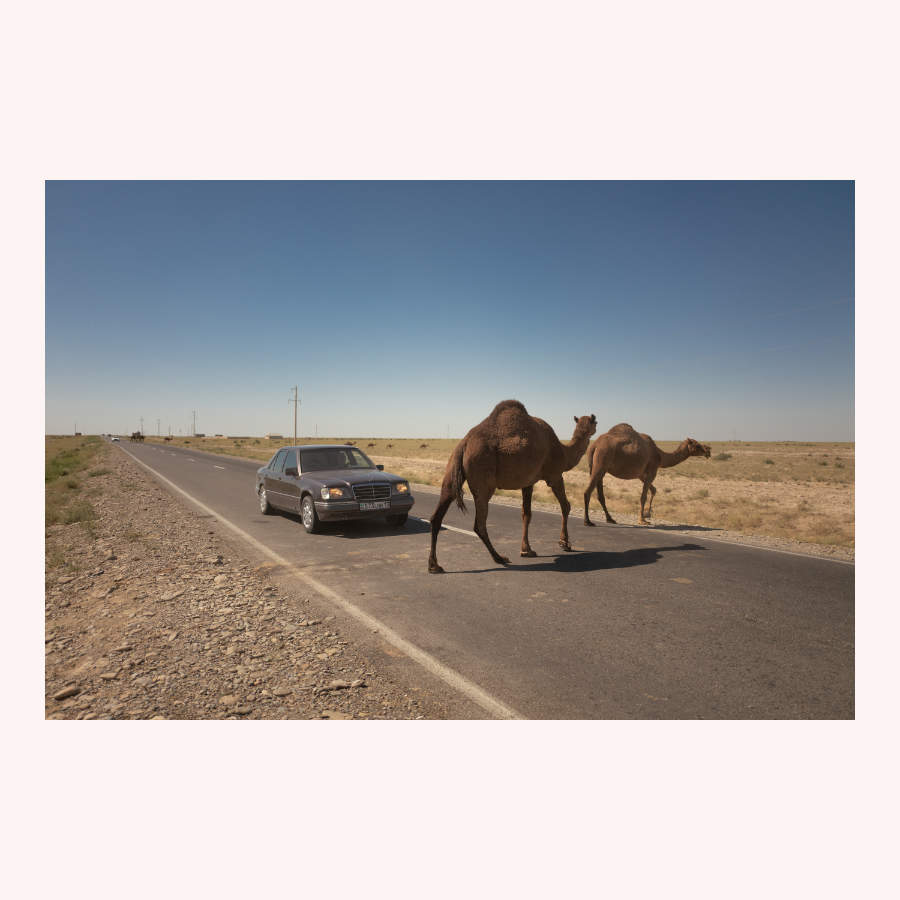

Baikonur sits on the barren steppes in the south of Qazaqstan (previously “Kazakhstan,” but the country is now amidst a latinization of their written language). It is flat and arid, timeless and treeless, with a relentless wind and 300+ fair weather days each year. Stand on a small hill and the landscape can feel like the ocean. It is endless. It expands along edge of your vision in all directions. Half is earth, half a sky of mega-blueness, a lapis lazuli shaming blueness, a chest thumping blueness sprinkled to the horizon with small, cumulus puffs.

It is the landscape of Qazaq nomads, most all of whom were reformed or removed during soviet times. Baikonur itself was a village. Then selected for the Cosmodrome. It satisfied a number of requirements to aid in shooting things into space. The infinite flatness of the steppes made it easy to find space stuff as it plopped back to earth. Another benefit: “southernness.” The closer to the equator, the easier to shoot things up. Though Baikonur is nowhere near the equator, it is much closer than anywhere else in Russia.

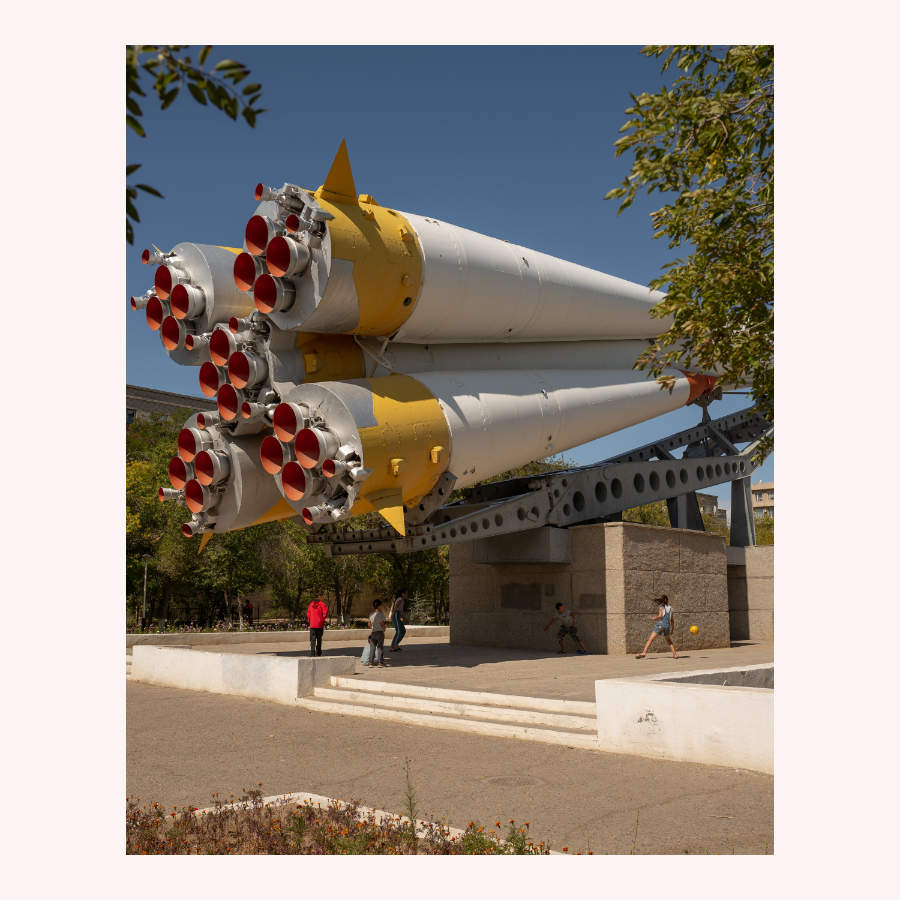

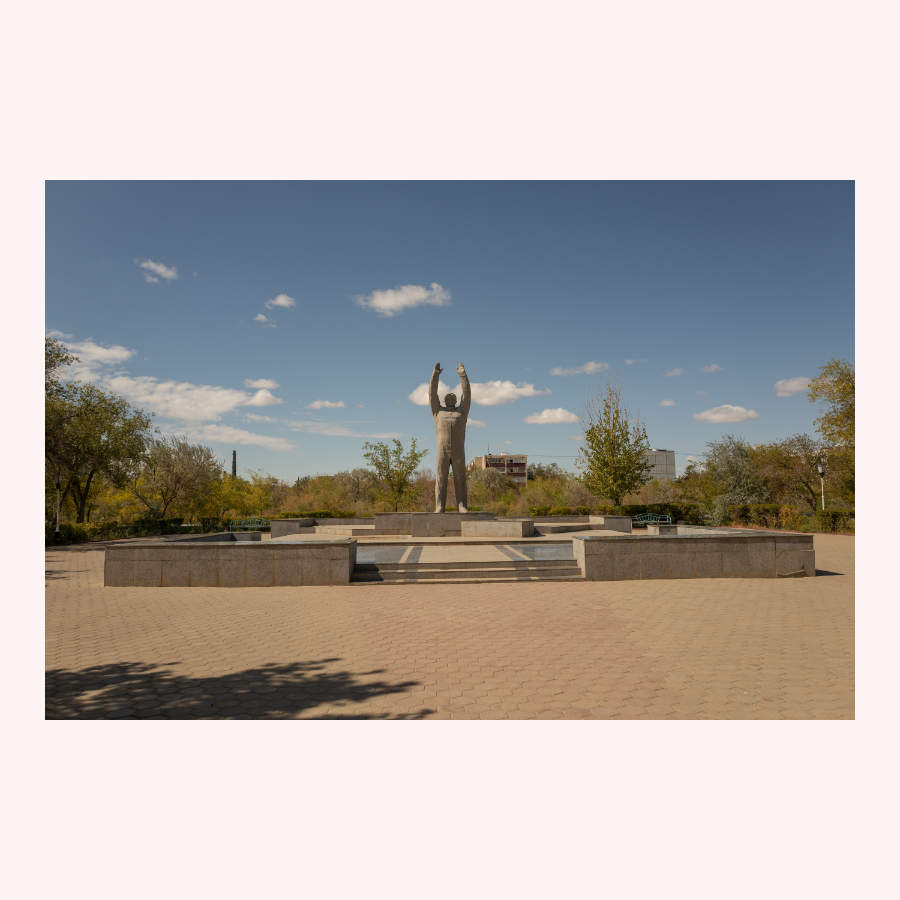

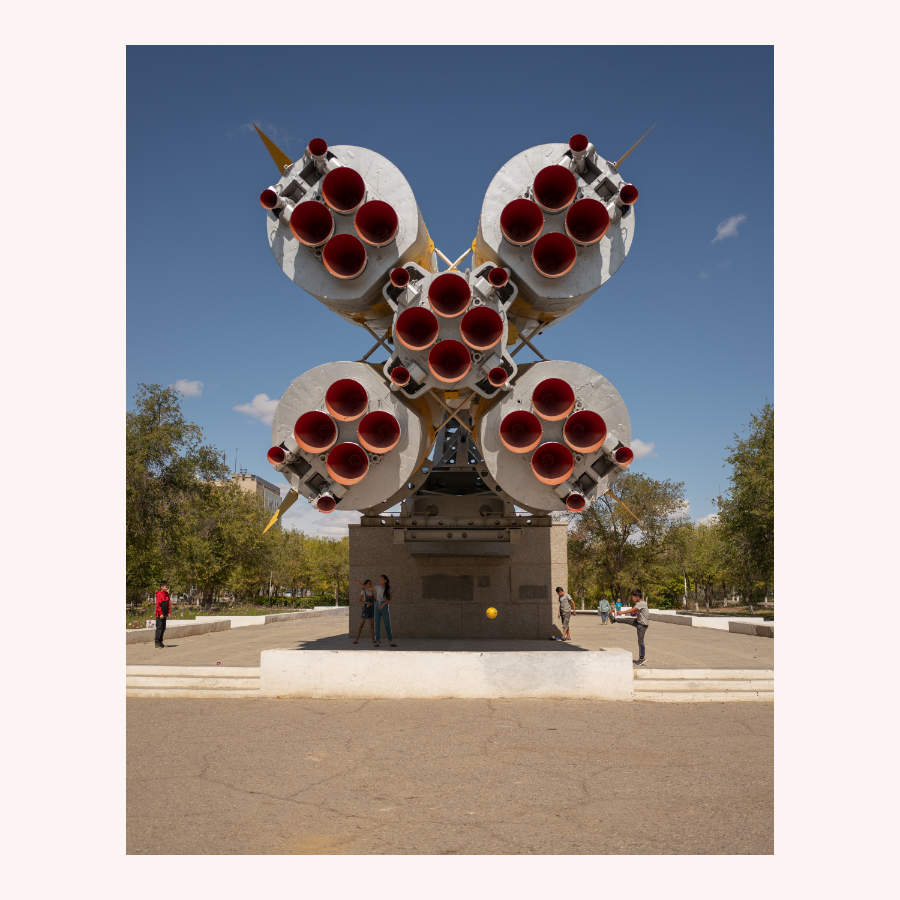

The village turned into a town, perhaps even on a given day you could squint it into a city. Construction began in 1955 and things were humming by 1957. Sputnik 1 — that iconic, gleaming, mirrored, polished orb (easily imagined going totally stealth against the backdrop of space) with four straight tails — went up on October 4, 1957 lighting a fire under the asses of the American military. Sputnik made 1440 orbits. Rats went up. Rabbits. Dogs. Then: Gagarin went up on April 12, 1961, squished into a child pose in his wee space seat within the Vostok 1 payload, becoming the first human to successfully orbit the earth (just once, just a quick up and down). ICBMs were installed underground and tested at Baikonur set off by launch keys (heavy, steel things with fat rings that would fit on no keychain). Dogs and nukes: Baikonur became a classic mid-century modern freakout, both a place of scientific reverence and total annihilation. Today, the nasty stuff is gone and, like CERN, it’s a place of international collaboration.

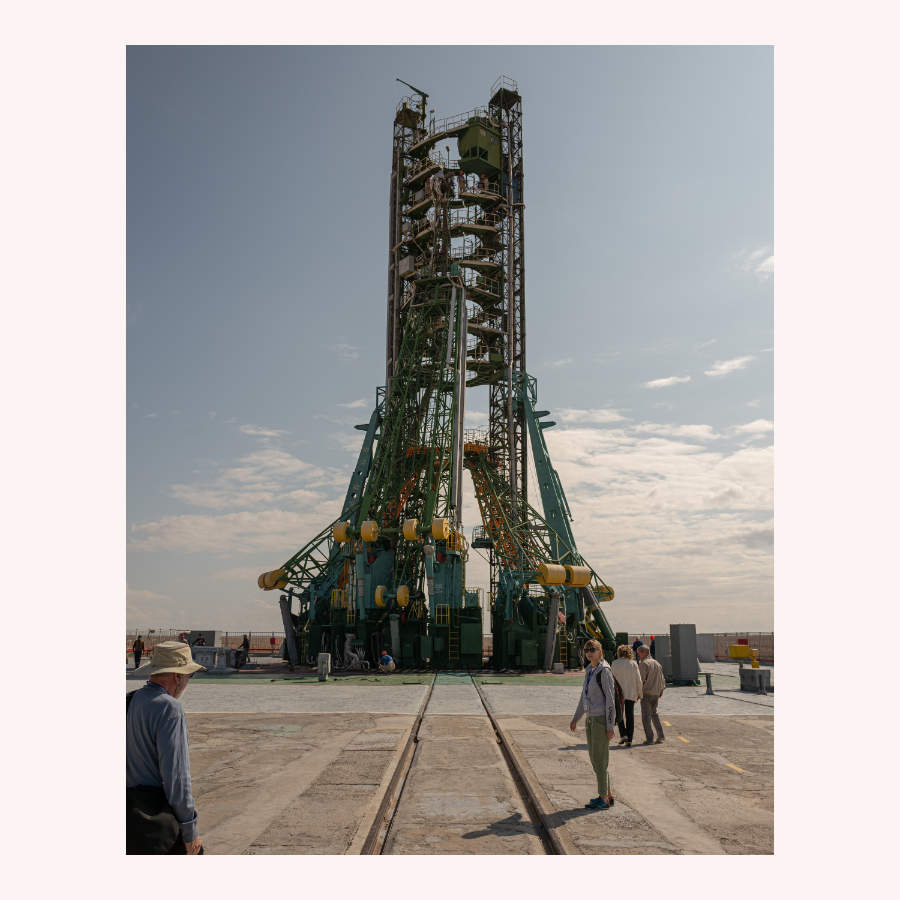

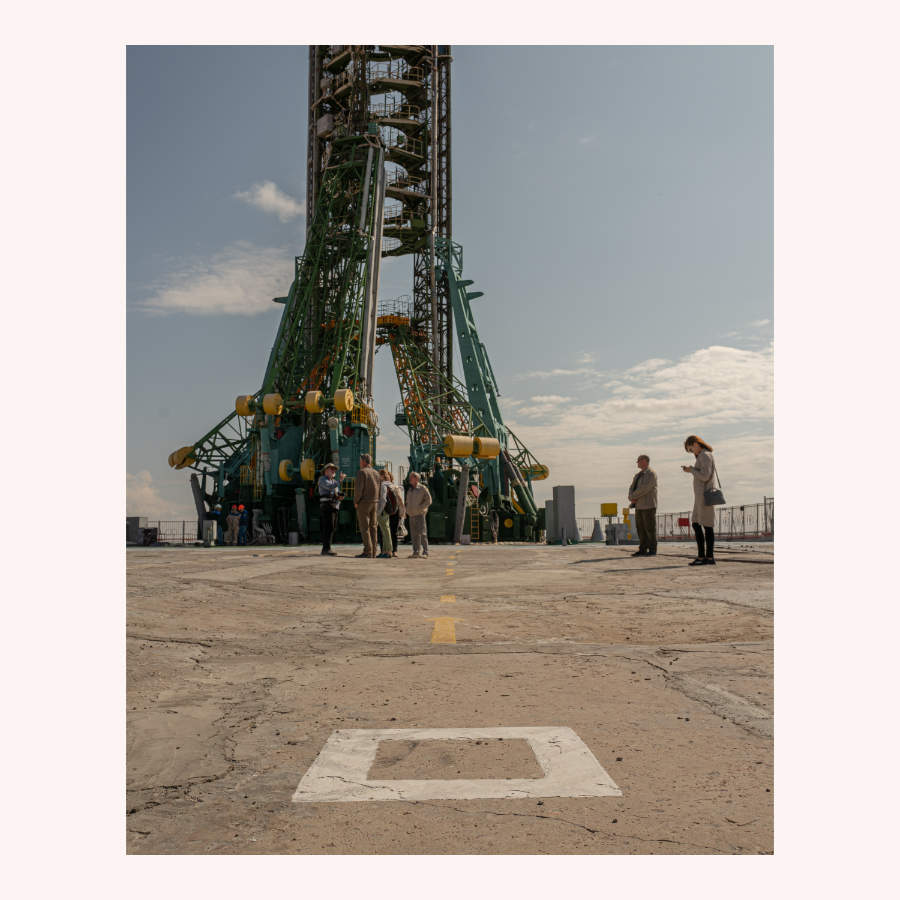

Was our access special? I don’t know. All I know is we didn’t see a single other visitor to the Cosmodrome that day. (We did see a team of Americans there to assemble a satellite.) Everyone asked why were we there when we were. Didn’t we, like, know that in just two weeks a Soyuz rocket — the only rocket still able to vault the human body towards stars (NASA no longer has this capability) — will send four cosmonauts to the International Space Station?! Didn’t we want to see the launch? Of course, but for whatever reason we were visiting now not then. We were, it seemed, buffoons.

But lucky buffoons. For it turns out, now was a damn fine time for a Cosmodrome stroll. The place thrummed and purred in anticipation of the launch and we were able to watch the weirdness of all the preparation up close. Far closer than we could have gotten on launch day. Launches are over in minutes. We had hours with the site.

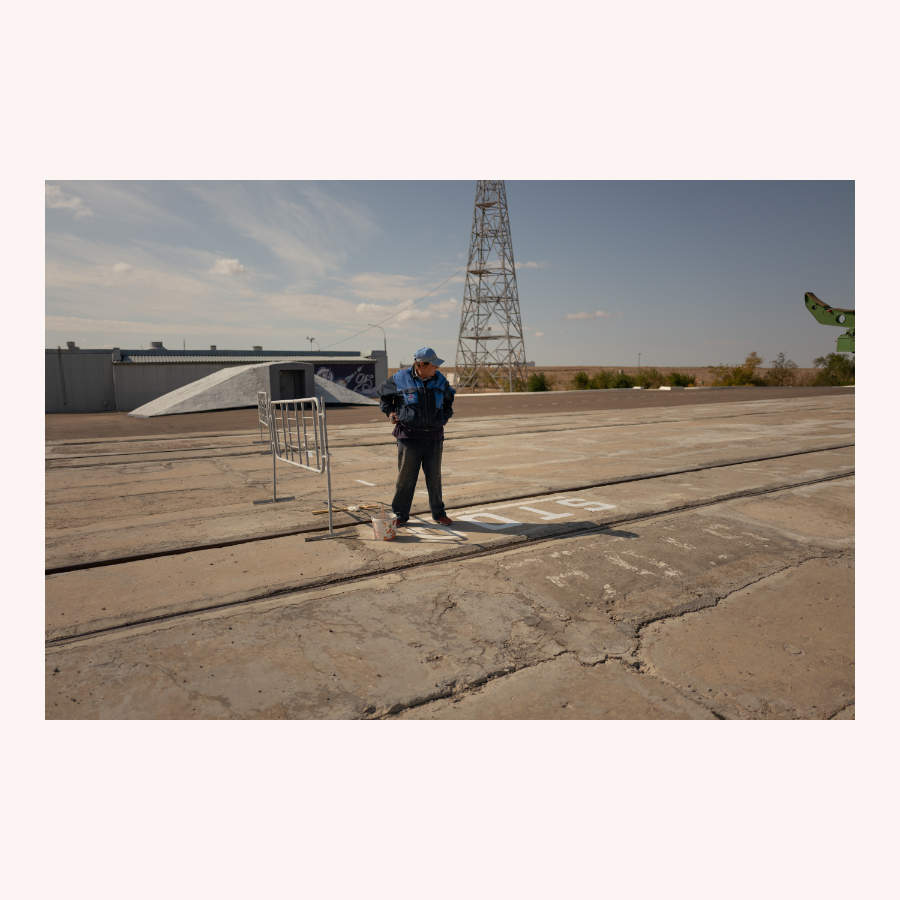

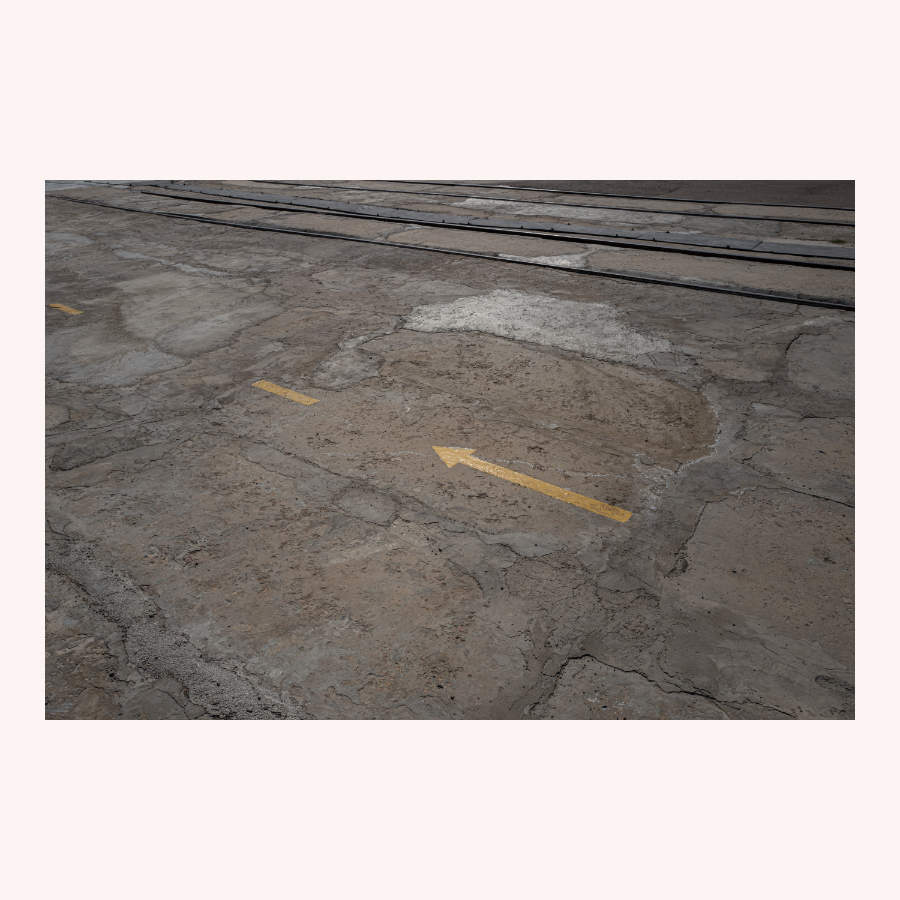

There are many launch sites at the Cosmodrome. We were escorted to the first launchpad, Gagarin’s launchpad, also known as NIIP-5 LC1, Baikonur LC1, LC-1/5, LC-1 or GIK-5 LC1 — the same site from which the astronauts will launch in a few weeks. We walked the runway, touched the old rail line that will carry the rocket to the launch pad at the gentle walking pace of three kilometers per hour. We stood in the painted squares where the astronauts will stand for a final check before walking along a dashed yellow line to the elevator transporting them to the top of the rocket for boarding. We were within meters of the launch scaffolding. It was somehow smaller (shorter?) than expected. Walked the edge of the burrowed-out exhaust pit — like an underground colosseum — and took in the whole site of awe as a single panorama. We were reduced to drooling children.

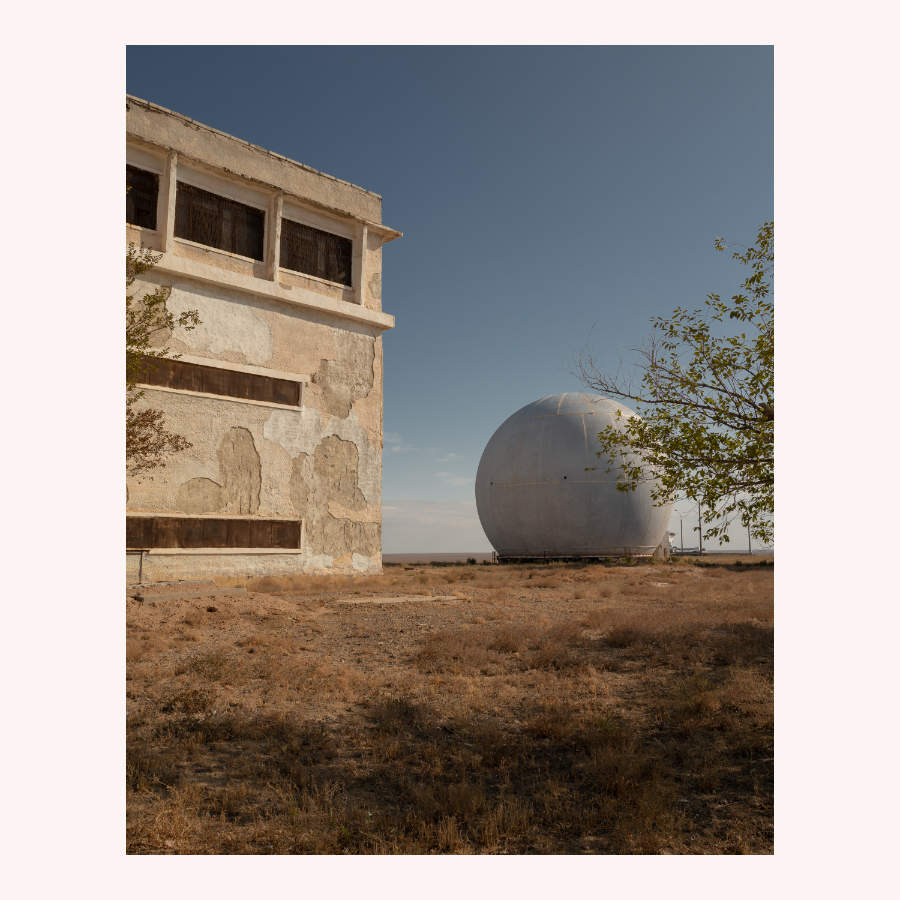

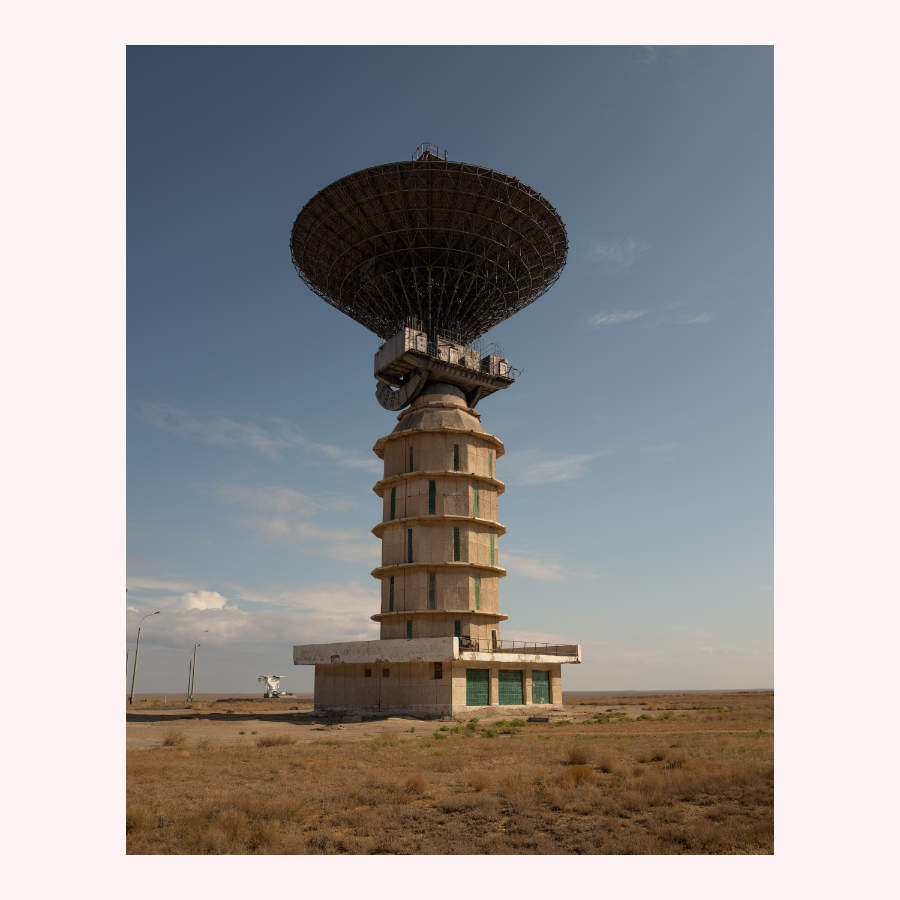

Other things we saw during our many-kilometer walk of the Cosmodrome: Roofs being painted, fences being painted, door thresholds being painted, road signs being painted. Painted with an intensely pungent paint. How were the unmasked painters not falling off the roofs? We didn’t know. We saw gardeners raking dirt and weeds along the edge of the launch site. We saw dozens of camels grazing nearby, scraggly stray dogs roaming the grounds. We fed their puppies bread. We saw old satellite dish transmitters and receivers long-since unused, paint peeling, flocks of birds living in their latticework like objects excavated from Tatooine. We saw the collapsed roof that killed eight and destroyed one of the few Soviet-made Buran spacecrafts. We saw old men pouring Soviet-style wax seals used to discourage tampering with drawers or opening doors that shouldn’t be opened. We entered a blast-safe bunker and saw a rocket launch control room (one part Wargames, one part Maniac), not in use for over thirty years, but with active control panels and blinkenlights and scanline patterned CRTs, rubber earpiece headphones and chairs askew, the scene like everyone ran off in the middle of an attack and nobody had ever bothered to turn the mechanisms off.

Each person we met was gracious, solicitious, patient with our obsessive dorkery and recondite nitpicking. We were a group of moony ding dongs, slack-jawed wonderment machines. I was mainly in admiration of the rawness of it all. The launch site in particular felt like something you could construct in your own backyard given enough time and steel, kerosene and oxygen.

One by one our handlers departed. Tips were offered and vehemently refused. Hands were placed against hearts. Checkpoints were passed more quickly in reverse and eventually we found the cosmodrome receding into the distance, the landscape reverting to the dusty nothingness of the steppes, pocket full of rubles, Lenin Square somewhere ahead.

Below: More postcards.

Note to self: Watch that launch.

Note to all: If given the chance, take a walk around Baikonur.

Until next week,

C

Your gentle weekly reminder: This newsletter is made possible by members of SPECIAL PROJECTS. If you’re enjoying it, consider joining. Thanks.

Fellow Walkers

“City walker here. I grew up in Southern California, where driving was a way of life. Walking seemed… absurd. When I developed a nasty panic disorder around my 30th birthday, my doctor ordered me to exercise more. I decided to walk several miles for my morning coffee, and I started to love walking. Now in NYC, I have no car by choice and walk all the time. Sometimes I’ll get off the train several stops early just to see, for example, what a particular part of the city feels like at 10pm on a Tuesday.”

“I’m from the south of England, wedged between the sea and a series of hills called the South Downs. This means I’m given the joy of choice between hillside or beach walks, all themselves well within walking distance. I moved to the big city for spells (University, my first ‘proper’ job) but have since moved back, called by the sea. I use walking as a tool of discovery, travelling by foot to explore whatever new city I find myself in, whether I’m accompanied or travelling solo. I’ve yet to come home from somewhere new without hardened feet to remind me of the experience.”

“What made me who I was? Being forced to create in deserts.”

(“Fellow Walkers” are short bios of the other folks subscribed to this newsletter. In Ridgeline 001 I asked: “What shell were you torn from?” and got hundreds of responses. We’re working our way through them over the year. You’re an amazing, diverse crew. Grateful to be walking with you all. Feel free to send one in if you haven’t already.)