It’s been a week since the walk ended and today — today — is the first day I’ve been even slightly still. I returned and dove right into helping a friend with a project in Tokyo. One of those 72-hours-straight, move-a-few-mountains kinda things. He left Sunday. Monday I collapsed but flitted about my ’hood. Today I was largely horizontal.

This morning I went for my first acupuncture session in probably ten years. Ninety minutes; it was done before I knew it. The practitioner’s stomach rumbled something crazy the whole time. At the end he said to me: I’ve never seen someone with such blocked ki. And then he said: Did you hear my stomach? That’s how much energy I was putting into unblocking you.

We’ve talked about the physiology of walking before. I’m not sure my body is a great walking body. It can do it. And it performed admirably over my 43 walking days. But there are most definitely better suited bodies out there. I was in constant maintenance mode: shiatsu massages when I could find them, stretching, icing, lots of ibuprofen. Knocking out 30km+ a day is — I now know — a serious physical act to contend with. Add to it the pack, the weight, and the asphalt-jolt of each step and things are bound to need servicing.

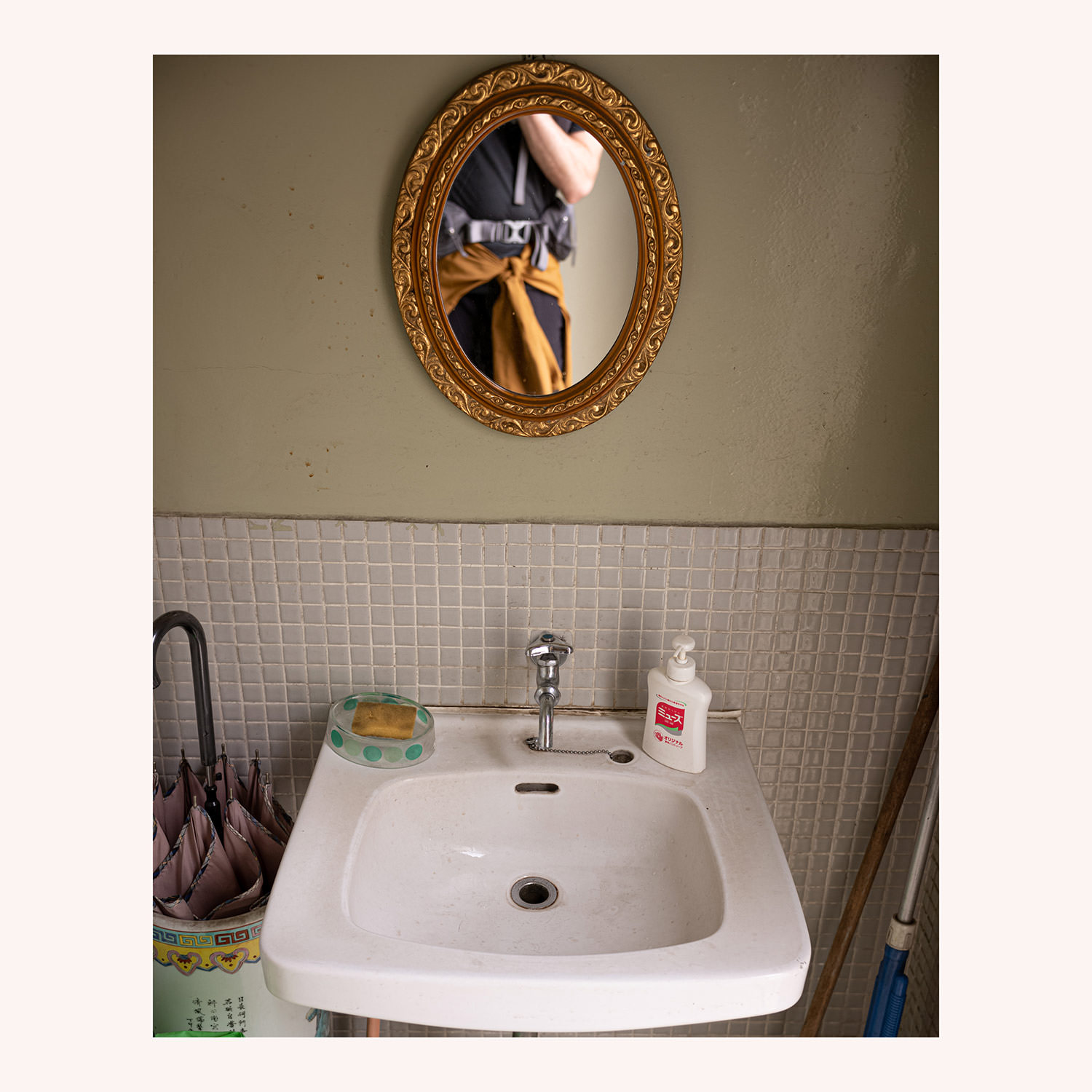

My shoulders were the first to bruise. I hadn’t properly adjusted my pack. I was using a PD clip to clip my camera to my pack strap, and so my left strap had an extra kilo of weight on it. Five days in, the pain was a wee bit much, prompting me to remember how to properly position and tighten my belt and shift most of the weight to my hips. This changed everything. I could carry an elephant now. Relieved of unnecessary duty, my left shoulder turned from deep purple back to beige, and in exchange, my two hips were chaffed a beautiful, burning red by day ten.

Around the time my hips went frictive, my left foot began to ache with a worrisome acuteness. My feet are pretty flat. Not completely, but enough to understand why the army isn’t too keen on flat-footed soldiers. My left is flatter than my right. New insoles, higher arches, fixed the pain almost immediately.

But then the knees acted up. So I started using braces and icing. I’d buy a sack of ice from a conbini each night. Eventually I grabbed a proper icing bag. Combined with the brace, it was a great system.

But then the brace started chafing the hair on my left leg, so I shaved it. I shaved it surrounded by naked old Japanese men while looking out onto a night-lit Hikone Castle in the distance.

My socks? They were a little too compress-y, and so my pinkie toes were pulled in a little too tightly, resulting in both of them blistering over and over. They’re currently two hard little husks.

I bring all this up because folks rarely talk about maintenance. It’s so staid. But it was everything on the walk. It became a badge of the difficulty of the enterprise. I either doubled down on maintenance or I went home. Maintenance was a cascade of small problems to be solved. One solution often creating a new problem. But the reward at the end of the day — the sense of having moved through the world and the satisfaction of my various output streams — was well worth the effort.

This is to say that most all good work is hard work. And most all good work — creative or otherwise — requires tremendous maintenance. Iterations, false-starts, blisters, bumbles, bruises. You will screw up. You will be rejected. You will write the wrong novel. You will probably suffer from a fumble. But that’s part and parcel of the tacit agreement we all have with the universe. The universe says: Hey, here’s a few micro-micro-micro moments of existence. And we say: Alright, ya stingy bastard, here’s my best shot.

Best shots may leave you flat on your back. Ki all blocked up. But the acupuncture man is there. And your exhaustion will tire him out, make his belly rumble. But then at night, writing, seated at your round table in a quiet living room, fans blowing, you’ll feel like you’re once again floating, the body impossibly light, the unblocked ki circulating like a vape pen at a dinner party in Brooklyn.

The big WIRED piece came out last Wednesday. It starts with a vignette that would have otherwise been a Ridgeline.

Further down, some notes on hellos. Have you said hello to a dozen strangers today? Give it a try.

A snippet:

LET ME MAKE it clear: I was luxuriously, all-consumingly bored for most of the day. The road was often dreary and repetitive. But as trite as it may sound, within this boredom, I tried to cultivate kindness and patience. A continuous walk is powerful because every day you can choose to be a new person. You flit between towns. You don’t really exist. And so this is who I decided to be: a fully present, disgustingly kind hello machine. I said hello to bent-over grandmothers and their grandchildren playing in rice paddies. I said hello to business folk about to hop into their Suzuki Jimny jeeps, to Portuguese workers on break from car factories, to men in traditional fundoshi underwear about to carry a portable shrine in a festival. I greeted shop owners cranking open their rusted awnings and a man selling chocolate-dipped bananas. I’d estimate a hello return rate of almost 98 percent. Folks looked up from their gardening or sweeping or bananas and flung a hello back, often reflexively but then, once their eyes caught up with their mouths and they saw I was not a local, not one of them, their faces shifted to delight.

I felt as if the walk itself was pulling that kindness from me, biochemically. The feedback cycle was exhilarating. It was banal. It was something I rarely felt when plugged in online: kind hellos begetting hellos, begetting more kindness.

For now, sleep. So much sleep. The ki, it flows to dreamland.

C

Your gentle weekly reminder: This newsletter is made possible by members of SPECIAL PROJECTS. If you’re enjoying it, consider joining. Thanks.

Fellow Walkers

“I hiked along a former border last year, bit over 1000 kilometers, between what used to be two separated countries. It was my first hike. I’m born on one side, spent half my life there, then moved to the other. I had no idea what shell I was torn from. The hike had an answer for me that I didn’t see coming. So much of me is of that country that ceased to exist, because of course. Processing / walking continues.”

“The shell I’m torn from is the Adirondack Mountain Park. I was raised in Lake Placid, NY–where that famous Winter Olympic game occurred where the US Hockey Team defeated the Russians. Have you ever been for a walk up there? I highly recommend it. (Obviously.) Maybe someday it would be nice to take a walk with you up there. My father, who was at the game, has a poster in my childhood home of the hockey team with signatures of every US team member. He likes to say, ‘If the house is burning down, leave everything except the poster, because it’s buying us a new house.’“

“I am greot torn

premature from the shell

of a land scored

through by ley lines

and the flights of hræfn;

of a nation

eulogised by the faded pink

of cartography dismissed

to the corner of the archive.”

(“Fellow Walkers” are short bios of the other folks subscribed to this newsletter. In Ridgeline 001 I asked: “What shell were you torn from?” and got hundreds of responses. We’re working our way through them over the year. You’re an amazing, diverse crew. Grateful to be walking with you all. Feel free to send one in if you haven’t already.)