Dearest sauntering pedestrians,

An eagle-eyed reader wrote in to correct William Scott Wilson’s romanization of “yuusan” as yusan (遊山 — jaunt, excursion, etc) and now we’re wondering if his whole phrase isn’t off. From last week: "… the most numerous travelers on the gokaido — and particularly on the Nakasendo and the Tokaido — were the yuusan ryokyaku, people traveling for pleasure."

Scholars in reading! Can you help us figure out the precise transliteration and kanji for this phrase? Many thanks in advance.

Your gentle weekly reminder: This newsletter is made possible by members of SPECIAL PROJECTS. If you’re enjoying it, consider joining. Thanks.

Five years ago I visited Saga Prefecture amidst a kind of walk-train-walk adventure that took a few friends and me down to Yakushima and then up Kyushu towards Fukuoka. Much fun was had — good hikes and food and laughs — but the biggest impression on me wasn’t made by the gnarled old yakusugi of Yakushima (impressive, though, they were) but rather a ryokan where we spent one of our last nights.

The inn is called Yoyokaku, and it’s run by a man who likes to be called Den-san. “Mr. Den” or “Okochi-san” or, even, “Okochi-sama” would be more polite and perhaps more standard. But “Den-san” — the mix of his maybe-first name that his international guests know him by, and the Japanese half-honorific — feels just about right for this man who has spent a lifetime bridging cultures.

Over the years I’ve stayed in many ryokans. Why did this one impress? Because it was a faultless object. In so much as the experience of staying at an inn can be a singular, bounded thing. That is, the interface to the place itself — all of its surfaces — were, as far as I could tell, perfect. I couldn’t imagine better versions of them: The silken hardwood floors smoothed under a century of stocking feet and slippers. The large glass panes, still original, mostly, and of that precisely imperfect turn-of-the-century cut, shimmering and making the garden do a watery dreamscape dance. And then the garden itself! The dozen matsu pines kept up, despite the high gardening costs. The proportions of the old rooms — visible wooden beams embedded into sunakabe — creating that pleasing sense of thirds and fifths and golden ratios wherever you happen to look.

But all of that paled in the shadow of the locks and door knobs.

Den-san is now about eighty seven years old. Before running Yoyokaku, he apprenticed in the early 1960s at my other very favorite Japanese lodge — The Fujiya Hotel in Hakone. (The Fujiya is currently under renovation until next year, and believe me, we fans are holding our collective breath hoping they don’t ruin the je ne sais quois messy surrealness that made it so wonderful.) He was there for only a few years. Felt like he had learned enough. Came back across the country and set up perch in Yoyokaku.

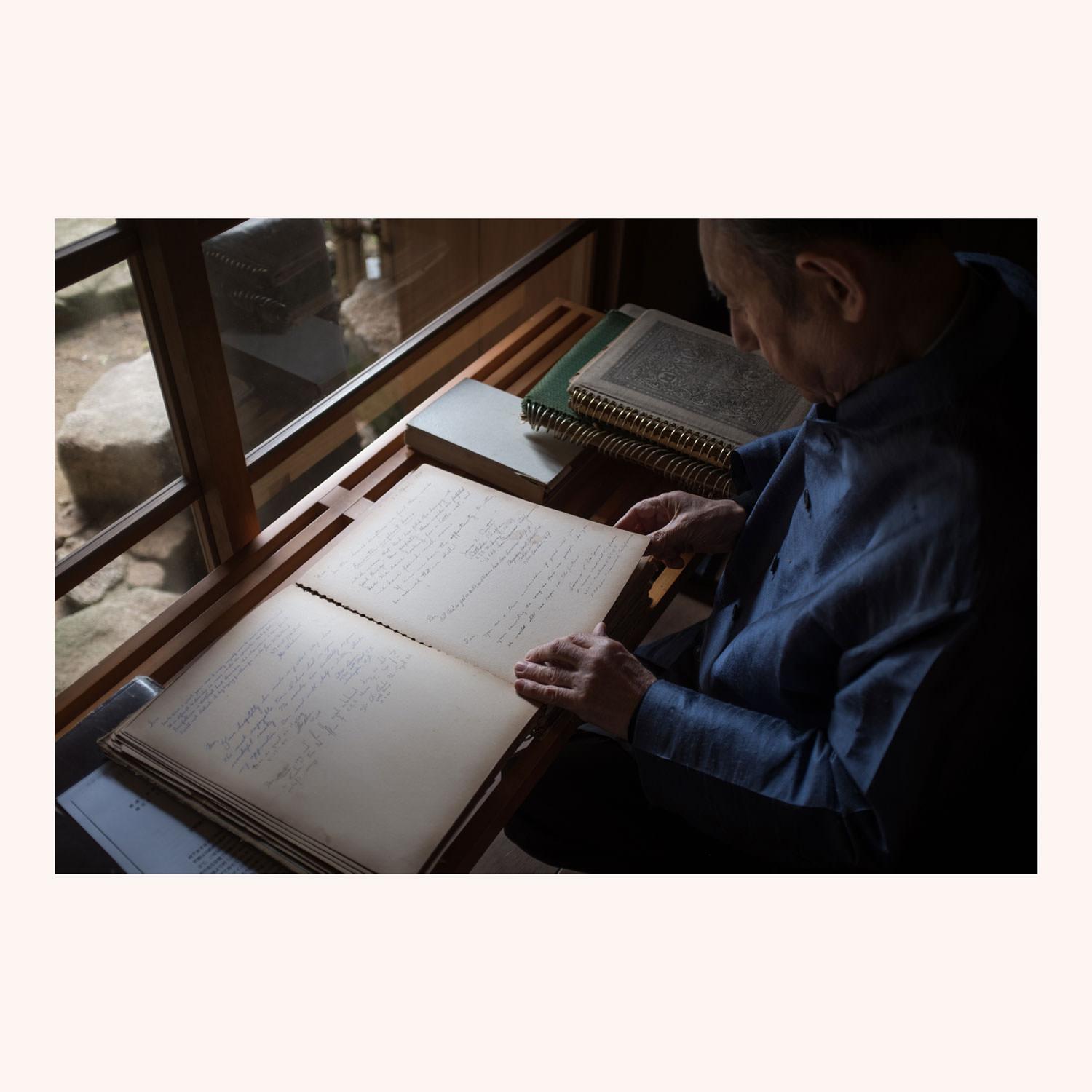

He’s been there ever since. I took the photo above as we went through his decades of meticulously maintained guest books.

During Den-san’s long tenure, Yoyokaku has been restored and fixed up a number of times. Even so, the building maintains a clean through-line, doesn’t feel modified or restored. As you walk the creaky halls, you feel the reverence Den-san picked up at The Fujiya for strangely considered, high-quality objects. And you feel it especially, markedly, whenever you enter or leave your room.

About those knobs and locks: Made by a company called Hori. Installed roughly thirty three years ago. These Hori locks are the same you would have found in the old wing of the fabled Hotel Okura in Tokyo, had you visited before they knocked it down.

During these intervening decades the Hori keyholes and door knobs (separate, of course; only barbarians combine the two) at Yoyokaku have developed that pleasing dull patina of worn brass having shed its paint.

Though they look beautiful, most of the awe of the user experience of the Hori lock is internal — the magic is in the feel of the mechanism. The keys themselves aren’t much special: They look like any old key. And yet when they are lost, taken home by accident, dropped in a drain, eaten by a hawk — as keys tend to be — their replacement requires considerable hand wringing and hemming and hawing as you can’t just cut a new copy but instead have to send Hori the serial number to have them forge a new one in their special furnaces. So, they are more unique than they seem at first blush. And then — then — you stick it in the pretty old lock and your life changes.

The Hori key enters a Hori lock in such a way as to affirm your suspicion that every key you’ve ever inserted into every lock throughout your entire life was a sham. A false combination — jittery, sticky, imprecise. You realize how badly cut, forged by shoddy means, all the keys you own currently are. Using this Hori key and lock combination is similar to how you might have felt the first time you ever touched a masterfully finished piece of wood — shock at that glassy smoothness you didn’t think could be brought out from the material.

The key enters. Within perfectly milled chambers, the driver pins — attenuated by precisely tensioned springs — push against the key pins as the key slides forward in the keyway. The driver pins align to a dead-straight shear line and you feel the key settle with a satisfaction of a meticulously-measured thing spooning its Platonic opposite. Then you twist. The movement of the bolt away from the frame is so smooth — the door having been hung by some god of carpentry with the accuracy of a proton collision path — that you gasp, actually gasp, at the mechanism.

As I walk and stay at inns across the country, I think back longingly to the locks at Yoyokaku. Rarely do others hold up.

Den-san likes to chat. We stayed up late into the night sipping whiskeys on rocks on my last visit. We drank slowly as I interviewed him in his well-lit, warm parlor, surrounded by books. He’s lived a full and joyful life, one of seemingly endless serendipities and connections and goodwill. I wanted to profile him and The Fujiya — some kind of classics-of-Japan combo, human and structure — but never got around to it. I asked him about the locks and he just shrugged and said, “Yep, pretty good.”

No, Den-san. Flawless. Just like everything else in your wonderful inn.

Until next week,

C

Fellow Walkers

“Casseroles, merit badges and apostasy. I now walk the streets of Tokyo with my past so conveniently far away.”

“I grew up in late 80’s / early 90’s Northern Ireland, and while I didn’t think too much about the effect the capital-T Troubles were having on me then, I look back now and, yikes.”

“I used to joke that it was England’s puddles that gave me itchy feet, but now I realise my itinerancy is inherited. My parents and grandparents’ migrations once seemed inconsequential, monolingual as they were. But the older I get, the more I realise that these were wrenching in their own way. And that trying to escape the family, funnily enough, runs in the family. “

“This is a village in Dalmatia of about 800 people. Roman aqueduct remnants. A medieval crusader castle. An ottoman hotel. 100,000 migratory birds on its lake. Seasonal walking club membership count maximum is at 003.”

(“Fellow Walkers” are short bios of the other folks subscribed to this newsletter. In Ridgeline 001 I asked: “What shell were you torn from?” and got hundreds of responses. We’re working our way through them over the year. You’re an amazing, diverse crew. Grateful to be walking with you all. Feel free to send one in if you haven’t already.)