Post-Artifact Books and Publishing: Digital's effect on how we produce, distribute and consume content.

— Craig Mod, June 2011"Roger Bacon held that three classes of substance were capable of magic: the herbal, the mineral, and the verbal. With their leaves of fiber, their inks of copperas and soot, and their words, books are an amalgam of the three."— Matthew Battles, Library: An Unquiet History1

What is a book, anymore, anyway? 2

We will always debate:

the quality of the paper, the pixel density of the display;

the cloth used on covers, the interface for highlighting;

location by page, location by paragraph.

Stop there.3

Hunting surface analogs between the printed and the digital book is a dangerous honeypot. There is a compulsion to believe the magic of a book lies in its surface.

In reality, the book worth considering consists only of relationships. Relationships between ideas and recipients. Between writer and reader. Between readers and other readers — all as writ over time.

The future book — the digital book — is no longer an immutable brick. It's ethereal and networked, emerging publicly in fits and starts. An artifact ‘complete’ for only the briefest of moments. Shifting deliberately. Layered with our shared marginalia. And demanding engagement with the promise of community implicit in its form.

The book of the past reveals its individual experience uniquely. The book of the future reveals our collective experience uniquely.

For those of us looking to shape the future of books and publishing, where do we begin? Simply, these are our truths:

The way books are written has changed.

The canvas for books has changed.

The post-published life of a book has changed.

To think about the future of the book is to understand the links between these changes. To think about the future of the book is to think about the future of all content. So intertwined are our words and images and platforms, that to consider individual parts of the publishing process in isolation is to miss transformative connections.

These connections shaping books and publishing live in emergent systems behind the words. Between the writing and the publishing, publishing and consuming, consuming and sharing.

We have an opportunity now to shape these systems. And in doing so, to refine the relationships between authors, publishers, readers and texts.

What tools will we embed within digital artifacts to signal this shifting relationship with literature?

To surface our shared experience?

To bridge the raw pre- and post- artifact spaces that so define the future of publishing?

To build the future book?

1. The Book, a System

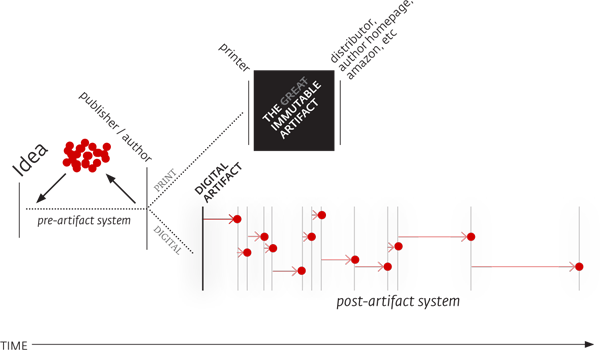

Classic Publishing

Two+ years between Idea and Reader

A lonely, isolated pre-artifact system.

An immutable non-networked artifact.

A near non-existent post-artifact system.

Books are systems.

They emerge from systems. They themselves are systems — the best of which are as complex as is necessary, and not one bit more. And once complete, new systems develop around their content.

To understand where books and publishing are moving, it is critical to understand the following three systems:

- the pre-artifact system

- the system of the artifact

- the post-artifact system

A system of isolation,

involving very few people.

The pre-artifact system is where the book or story or article is made. It’s a system full of (and fueled by) whiskey, self-doubt, confusion, debauchery and a general sense of hopelessness. Traditionally, it’s been a system of isolation, involving very few people. The key individuals within the classic manifestation of this system are the author and the editor. A publisher, perhaps. A muse. But generally, not the reader. The end product of this system is what we usually define as ‘the book’ — the Idea made tangible.

The artifact — the book — too, is a system. Traditionally, an island unto itself. Immutable. A system self-contained. One requiring great efforts to extend beyond the binding. When finished, it becomes a souvenir of a private journey.4

Finally, the post-artifact system. This is the space in which we engage the artifact. Again, traditionally a relatively static space. Isolated. Friends can gather to discuss the artifact. Localized classes can be constructed in universities around the artifact. But, generally, there is an overwhelming sense of disconnection from the other systems.

Digital changes this.

Most fundamentally digital removes isolation. Removes it from the pre-, artifact, and post- systems. The corollaries: an increase in connectivity. Mutability of artifact. Continuous engagement with readers. And most excitingly, a potentially public record of change, comment, discussion — digital marginalia — layered atop the artifact, adding to the artifact, and redefining ‘complete.’

With the connection of these systems, our classic definition of a literary artifact no longer applies. And our common understanding of publishing systems is irrevocably disrupted.

2. Pre-Artifact Systems

With the emergence and growing adoption of the Kindle and the iPad, publishers, writers, readers and software-makers have concerned themselves with shoehorning the old-media image of a book into new media. Everyone asks, ‘How do we change books to read them digitally?’ But the more interesting question is, ‘How does digital change books?’ And, similarly, ‘How does digital change the authorship process?’5

This authorial shift is critical to the understanding of the new pre-artifact system.

The injection of readers early into the authorial process.

With digital impermanence (a new kind of ephemerality) comes two concepts key to the future of storytelling and books:

- We can continuously develop a text in realtime, erasing the preciousness imbued by printing. And because of this ...

- Time itself becomes an active ingredient in authorship (in contrast to authorship happening in a seemingly timeless place, a finished product suddenly emerging).

Wikipedia is a fully realized example of how digital drastically affects authorship. By creating a system that allows collective edits in real-time, Wikipedia has embedded iterative writing into its foundation. Nothing on that site is precious. No letter, word, sentence or article is immune to reconsideration. And yet, by tracking changes on a micro scale, they’ve built trust around a continuously evolving system.

Consider the physical analog to Wikipedia — the encyclopedia set. In the early naughts, it would have been difficult to imagine that a website written and edited by hundreds of thousands of people, constantly mutating, could have possibly formed the replacement for that dusty set of leather bound books on your bookshelf. And yet, not only has Wikipedia replaced the physical encyclopedia for many of us, but it’s surpassed it in usefulness, quality, timeliness6 and perhaps most significantly, convenience. The core editorial ethos of the physical encyclopedia still informs Wikipedia, but the ways in which content is created, shared, and edited are born from digital.

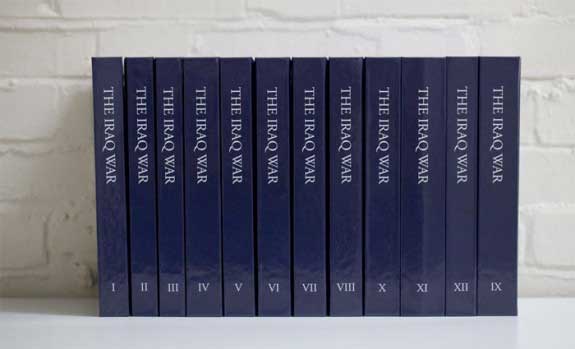

James Bridle's The Iraq War7

The entire Wikipedia editorial history for the Iraq War entry, printed and bound — the pre-artifact system manifest physically

Take a set of encyclopedias and ask, “How do I make this digital?” You get a Microsoft Encarta CD. Take the philosophy of encyclopedia-making and ask, “How does digital change our engagement with this?” You get Wikipedia.

When we think about digital’s effect on storytelling, we tend to grasp for the lowest hanging imaginative fruits. The common cliche is that digital will ‘bring stories to life.’ Words will move. Pictures become movies. Narratives will be choose-your-own-adventure. While digital does make all of this possible, these are the changes of least radical importance brought about by digitization of text. These are the answers to the question, “How do we change books to make them digital?” The essence of digital’s effect on publishing requires a subtle shift towards the query: “How does digital change books?”

2a. A few examples

(Companies and individuals leveraging changes in publishing systems):

As much as it may pain literary purists to admit, blogs have been laying the foundation for this kind of on-the-fly contemporary book writing for over a decade. 37Signals’ title, Getting Real, was composed over the course of years on their blog Signal vs. Noise.8 RSS subscribers to Signal vs. Noise had been reading Getting Real without knowing it. Heck, 37Signals had been writing Getting Real without knowing it.

Consider that they sold 30,000 PDFs at $19 a piece. That’s over half a million dollars in revenue (profit, really — there are no distribution costs or middle men). For a book that was authored publicly. And this, in 2006.

Frank Chimero9 has been sketching a book live. It’s his blog. He’s been working hard at fleshing out ideas around creativity and design for years now. And he’s built up such a community of supporters, they paid him $100,000 in February 2011 to go deeper. The Shape of Design promises to continue exploring the narrative threads on his site. To formalize.

In Spring of 2010, Ashley Rawlings and I ran a campaign to crowd-fund the production and publication of the second edition of Art Space Tokyo. 10 We raised $24,000 in a month. And shared the entire process in painstaking detail for others to replicate. 11

Robin Sloan12 has been writing and releasing short stories in digital formats for the grateful many of us fans. He is now returning to dive deeper into those pieces that had particular resonance with his intended audience — fleshing out shorter works into full length novels.

Amanda Hocking13 writes a blog. She also publishes her novels independently on the Amazon Kindle platform. They’ve done well. In the past year she’s sold over a million Kindle books.

John from I Love Typography14 has been writing a publication live. It’s — surprise! — his blog. And now he, too, (with the help of editor Carolyn Wood15 and friends) is formalizing his ideas into the bona-fide journal, Codex.16 Beautifully produced, masterfully edited, Codex is a collection of thoughtfully curated pieces on typography. A compendium of John's love for type wrapped, marketed and priced in a way that takes advantage of his amazing community. It leverages changes to the classic publishing system to make it self-sustainable.

Seth Godin has been so deeply influenced by his blog’s readership and the strength of his community that he threw his hands up and flat-out started his own publishing company. Domino17 comes from ideas that emerged in front of the audience he was ultimately trying to reach. It's a beautiful example of a sustainable ecosystem emerging from wholesome conversation.

The list continues indefinitely. To be even more hyperbolic: we are amidst undeniable, fundamental change to authoring processes. The friction and distance between you and your readership? Gone.18

... the subtle editorial push and pull by the number of page views and comments.

The ‘live iteration‘ born from these changes frees authors from isolation (but still allows them to write in isolation). The audience and author become conversant sooner. Writers can gauge reader interest as the story unfolds and decide which topics are worth further exploration. As 37Signals, Frank, John, Robin, Amanda and Seth refined their authorial philosophy before an audience of tens (if not hundreds) of thousands of readers, it’s easy to imagine the subtle editorial push and pull by the number of page views and comments they received on each blog entry. Which is to say, these frictionless, often indirect reader actions brought by digital to the pre-artifact system can manifest in the final authorial output.

Richard Nash of Soft Skull19 publishing fame and more recently founder of literary startup Cursor,20 has placed this pre-artifact system squarely in his sights. On why the disruption of the pre-artifact system is so necessary — hell, even morally required — he says: 21

We have tended to speak of the model of publishing for the last hundred years as if it were a perfect one, but look at all the indie presses that arose in the last 20 years, publishing National Book Award winners, Pulitzer winners, Nobel winners. What happened to those books before? They weren’t published! They. Were. Not. Published. Sure, some were, but most? Nope. We cannot know how much magnificent culture went unpublished by the white men in tweed jackets who ran publishing for the past century but just because they did publish some great books doesn’t mean they didn’t ignore a great many more ... So we’re restoring the, we think, the natural balance of things the ecosystem of writing and reading.

His new imprint, Red Lemonade, is built to elicit conversations around books. Often before they're complete. Certainly a terrifying notion for many, but also an inevitable product of the opening of the pre-artifact system. And like many things inevitable in the evolution of entrenched methodologies — you can either bemoan and lament and eulogize the old, or become an active participant in the shaping of the future.

Of course, no author is obligated to embrace or engage these changes. But these changes do beg the question: just where does the digital artifact begin and end? When is it ‘completed?’

3. The Fall of the Great Immutable Artifact

The digital book is a strange beast. It’s intangible and yet wholly mutable. Everywhere and nowhere. We own it, but yet, don’t.22 Its qualities mimic physical books only on a meta-level.

Have you ever edited and sent files to a printer to be reproduced several thousand times?

It’s terrifying.

To truly understand how strange and special they are, it helps to have experience with their analog cousins. Have you ever made a physical book before? What I mean is, have you ever edited and sent the files to a printer to be reproduced several thousand times? It’s terrifying. There is a pervasive hopelessness to the entire process. You know there must be mistakes. Check page numbers and punctuation a hundred times still, and by the sheer magnitude of molecules composing a book, you will miss something.

So submitting that file to be printed is to place ultimate faith in the book. To believe — because you must for the sake of sanity! — that this is the best you can do given the constraints. And you will have to live with the results forever.23

This is what makes physical so weighty. So precious. No matter how much you prepare, if you haven’t executed well, any misstep will be writ a thousand times over.

The multiplicity of books.

When someone says ‘book’ this is what we think of (but, curiously, we may be one of the last generations to think this). A very specific physicality. We imagine the thick cover. The well defined interior block. We feel the permanence of the object. Inside, the words are embedded in the paper. What’s printed there today will be the same stuff tomorrow. It’s reliable.

With digital, these qualities of printed books listed above become artificial. There is no thick cover constraining length. There are no additional printing costs for color. There is no permanence: the once sacred, unchanging nature of the text is sacred no longer. Updating digital text is trivially easy. When you look at the same digital book tomorrow, it may very well be different from the version you read today.

Outside of these obvious superficial differences, there are two qualities to digital artifacts that make them drastically different from physical artifacts:

- they have a deep, interwoven connection with the pre- and post- artifact systems

- they exist in the classical ‘complete’ form for only the briefest of instances

The connection with the pre-artifact system is obvious. For example, the ‘artifact’ output of a Wikipedia entry is a continued iteration — the product of a highly specialized pre-artifact system.

The artifacts emerging from Domino owe nearly everything to the existence of a pre-artifact system — the vetting of ideas on a blog, the conversation with readers.

Once a physical artifact is ‘completed,’ printed, boxed and shipped, it’s done. It can’t change.24 We may scribble notes in the margins of our copy, but the next person to pick up a different copy won’t see those notes. They get the same blank ‘complete’ edition we got.

For only the briefest of instances does the digital edition of a book exist in an untarnished, classic, ‘complete’ form.

For only the briefest of instances — seconds, perhaps, for popular authors — does the digital edition of a book exist in this static, classic, ‘complete’ form. The moment a Kindle edition of a book is downloaded and highlighted it has been altered. The next person to download a copy of that book will be downloading the ‘complete’ form plus all associated marginalia. And the greater the integration of systems of marginalia, the greater the impact that subsequent conversations around the book will have on future readers.

The digital artifact, therefore, is a scaffolding between the pre- and post- artifact systems.

Formats

This scaffolding between systems is defined in formats. EPUB, HTML, Mobi and iOS applications are the most popular. The most pervasive digital book format is undeniably HTML. EPUB and Mobi are effectively subsets of HTML. And woven into EPUB3 is the promise of robust HTML5, CSS3 and enhanced Javascript capabilities.

The most popular digital formats file into three neat categories. They are:

- Formless: ePub, Mobi, HTML

- Definite: PDF, EPUB3 (HTML5/CSS3)

- Interactive: iOS / Android, EPUB3 (HTML5/CSS3)

Formless and definite are concepts I outlined at length in Books in the Age of the iPad.25 Formless refers to content that has no inherent visual structure, and for which the meaning doesn’t change as the words reflow. Think: paperback novels.

Definite refers to content for which the structure of the page — the juxtapositionment of elements — is intertwined with the meaning of the text. Think: textbooks.

Interactive is, of course, for works that necessitate some interactive component: video, non-linear storytelling, etc.

There is overlap between these categories. Which is why we see some formats appearing more than once — EPUB3, for instance. You may need to have control over both the visual structure of a page as well as the interactivity it suggests.

iOS applications could fill all three categories, but it’s a tool not best suited for the job. We’ve seen this in iPad magazine design and distribution during 2010. Most of those magazines could have been PDFs or HTML5 documents. And readers would have been better for it (smaller downloads; selectable, searchable, resizable 'real' text, etc).

EPUB3 to rule them all?

EPUB3 seems poised to be the one format to rule them all. Why?

- Already, EPUB is light and well defined.

- Documents produced with it are inherently composed of real text and naturally integrate with everyman accessible distribution systems like iBooks, Kindle or as direct downloads from publishers.

- Moving forward, it will align with the latest HTML5 layout capabilities and allow embedding of robust javascript functionality for interactivity.

If the pre-artifact system incubates the artifact. And the digital artifact glues the pre- and post- artifact systems together. Then of just what, precisely, is the post-artifact system composed?

4. The Post-Artifact System

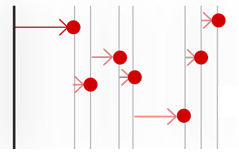

The Post-Analog,

Digital Publishing System

Marginalia layered atop the artifact

Artifact 'completeness' evolving over time

Reading is, if nothing else, telepathy. Stephen King, in On Writing, after describing a table with a red cloth, cage, rabbit and blue number eight:

I sent you a table with a red cloth on it, a cage, a rabbit, and the number eight in blue ink. You saw them all, especially that blue eight. We’ve engaged in an act of telepathy. No mythy-mountain shit; real telepathy.

But — and here’s the real magic — it’s a shared telepathy. A telepathy from one to many, and in that, the many have experiential overlap. Printed matter binds this experience to pulp. With digital, there is the promise of networking that shared experience.

We give form to our private telepathy through marginalia — marks, highlights, notes in the margins.

Years ago, I remember — before Kindles and iPads and before anyone knew of EPUB — hearing about the marginalia found in the books of Paul Rand’s library. I remember thinking how exciting it would be to browse his thoughts. To sort by them. To order them and share them. Use them as pivots for discussions. Comment around them. Draw lines from them and the books to which they were connected, to other books and the thoughts of other designers. To unlock, as it were, the marks of his telepathic experiences.

This is the post-artifact system. A system of unlocking. A system concerned with engagement. Sharing. Marginalia. Ownership. Community. And, of course, reading.

It's the system that transforms the book from isolated vessel for text into a shared interface.

It's a system that's beginning to appear in fits and starts in reading applications we use today. It’s the system most directly connected with readers. And it’s a system that, when executed well, makes going back to printed books feel positively neutered.

Layered marginalia atop the digital artifact, shifting the entry point of the work over time

Structurally, marginalia represents a potentially infinite layering atop the content. Manifested properly, each new person who participates in the production of digital marginalia changes the reading experience of that book for the next person. Analog marginalia doesn't know other analog marginalia. Digital marginalia is a collective conversation, cumulative stratum.

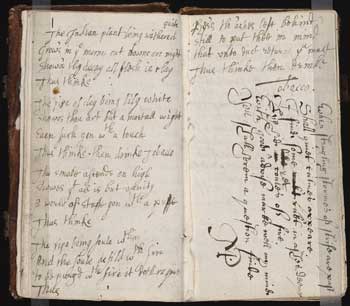

Marginalia is, of course, nothing new. Like old Paul Rand, as long as we’ve had books we’ve been scribbling in them. Spilling coffee on them. Covering them in the dirt and dust of travel. Sometimes deliberately, sometimes unknowingly marking them with memories.

One classic manifestation of this mental detritus is the commonplace book.27 Liz Danzico expounds:

When John Locke began taking notes in 1652, he did so in such an elaborate way that a publisher named John Bell published a notebook called Bell’s Common-Place Book, Formed generally upon the Principles Recommended and Practised by Mr Locke. This notebook, eight pages of instructions on an indexing method, was for the first time a way of making it easier to navigate an otherwise messy semblance of notes and thoughts. 28

Mid-17th century commonplace book. (Image via Wikipedia)

I outlined several requests for the networked book around notes and marginalia in my April 2010 essay Embracing the Digital Book.29 “Show me the overlap of 10,000 readers' highlighted passages in a digital book,” I demanded. “Let Stefan Sagmeister publicly share the passages he’s highlighted in the new Murakami Haruki novel.”

I then went on:

“When I’m done reading and marking a book, I should be able to create my own abridged copy. Show me just my highlights with notes. Let me export this edition. Let me email it to myself. Or, if you dare, automatically typeset it and let me order a POD copy for my personal library.”

Soon after I completed that article Amazon released their Popular Highlights functionality.30

Of all the large forces in the world of digital books, few are pushing forward as hard and fast as Amazon. They have already constructed the infrastructure for our networked commonplace books. Mine lives here. Seth Godin’s lives here. It needs work, of course, but it’s a start.

Beyond Books

This post-artifact space need not be saddled only atop books. The notions of community and engagement pivoting atop content can be applied to anything — magazines, blog posts, longform journalism.

Two things are necessary for true innovation and engagement to happen in this space:

- A well defined and open protocol. It is to this which all software and tools built to engage the post-artifact space can connect.

- The ability to construct canvas independent hooks beyond the reading space.

openbookmarks.org

Regarding the protocol, James Bridle with his Open Bookmarks31 initiative is pushing the conversation forward as to what the shape of this protocol might be.

Imagine a future where instead of lending someone a book, you lend them your bookmarks. Where your notes, annotations and references are synchronized across platforms and applications. Where your bookmarks belong to you, and a record of every book you read is saved and stored securely, no matter how or where you read it.

And then:

Open Bookmarks is a project to discuss and develop standards for saving, storing and sharing bookmarks, annotations and reading data in ebooks. Open Bookmarks will champion these principles and support widespread adoption.

EPUB3 seems to hold the most promise for constructing hooks beyond the reading space (outside of the Kindle or iBooks or Nook). Particularly so in the book space.

It’s fair to say building one-off, platform-dependent applications on a book-by-book (or issue-by-issue basis) doesn’t work very well. It's a stop-gap solution as distribution and rendering platforms settle and mature.32 EPUB3 brings with it the promise of standardization in allowing authors and publishers cross-platform post-artifact solutions. In other words: allowing readers to share conversations about their book, within their books, but independent of the service.

I asked Keith Fahlgren, of Threepress 33 and co-creator of Ibis Reader34 — just where EPUB is heading regarding the networked book. And specifically about those external javascript hooks. Regarding its current state in 2011 he said:

Apple already supports JavaScript in iBooks today (for EPUB pre-3), but they deliberately prevent network access for security reasons. I doubt they'll change their position very quickly.

But:

We expect some EPUB3 Reading Systems to allow JS network access for EPUB3 documents from "trusted parters" (this is probably what licensed versions of Ibis Reader will do). I have no idea if this will take off beyond a small subset of publishers in the medium term.

Still, the opportunity! We can define just how EPUB3 and the post-artifact space will align:

... EPUB3 is, at least for the next week or so, a blessedly empty canvas. If some cool publisher and Reading System felt there was a market opportunity for non-toy JavaScript and worked together on something that they promoted widely, I think it'd be quite possible that they could steer most EPUB3 Reading Systems (which are being built or to be built) in some direction or another. While JavaScript security issues for ebooks are quite real, there's also serious innovation in JavaScript land these days, as you know, so someone (probably well outside the ebook space) may come up with a compelling restricted subset of JavaScript (or something) that can have some network access but won't ruin everything.

Robin Sloan in his blog post, Inventing Books,35 reminds us of publishing innovation in the 15th and 16th century and concludes with:

This is all happening again, right now. Now sure: history’s not a spiral, and our case is new—the internet is not the printing press and the Kindle Store is not the Frankfurt fair. But there’s something in the feeling, if not the details, that’s the same. The great opportunity, the greater confusion—and greatest of all, the lure of invention.

So many questions: How often will tech geeks and lovers of literature have a chance to (re)invent our evolving relationship with books? While EPUB3 may hold promise for books, what about the rest of content? Who will provide the platform for the conversations around magazine articles? Longform journalism? Blogs? How will these spaces connect? Are there more interesting solutions than the currently deployed blog commenting tools?

There is a gaping opportunity to consolidate our myriad marginalia into an even more robust commonplace book. One searchable, always accessible, easily shared and embedded amongst the digital text we consume. An evocation — the application of heat to the secret lemon juice letter — of our shared telepathy.

5. Shifting Expectations

So — just what is a book, anymore, anyway?

To answer that is to look at the changes in our publishing systems.

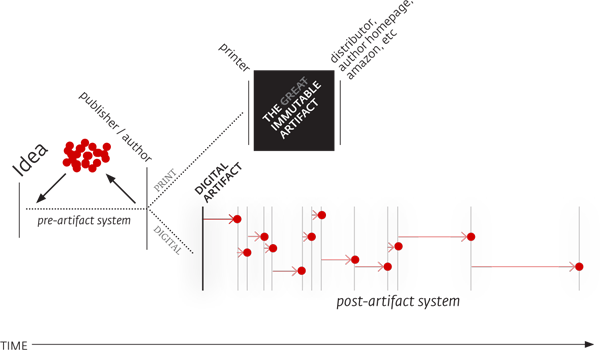

We've shifted from this:

To this:

Reading the changes from left to right:

- Engagement with readers (the building of community and conversation) begins immediately in the pre-artifact system.

- The two year disconnect between Idea and Readers is minimized to hours, days or weeks.

- The line between Publisher and Author is blurred.36

- If you choose to print, The Great Immutable Artifact is now only The Immutable Artifact.37

- The production time (from finished manuscript to readers' hands) of a digital artifact is significantly less than that of a physical book.

- The classic authority of access to distribution is heavily deemphasized in digital. Digital distribution channels such as Amazon's Kindle store and Apple's iBooks store are universally accessible. Anyone with an ePub file can reach critical, global points of sale.38

- A true networked post-artifact system of additive conversation and marginalia exists only digitally.

This, now

As I stated before, we will always debate:

the quality of the paper, the pixel density of the display;

the cloth used on covers, the interface for highlighting;

location by page, location by paragraph.

This is not what matters. Surface is secondary.

The ditch digging,

the setting of steel,

the pouring of concrete for the foundation of the future book.

This is what requires our efforts.

Clearly defined scope of these systems,

clearly defined open protocols.

These are what require our discussion.

Tools with simple, quiet, clean interfaces

organically surfacing our changing relationship with text.

These are what we need to build.

All of these efforts combined, these systems integrated,

these tools made well and deliberately.

This is the future book.

Our platform for post-artifact books and publishing.

Referenced or Noted

- If you're at all curious about the history of libraries, I highly recommend Matthew's exceedingly erudite book on the subject, painted with beautiful prose: Library: An Unquiet History. ↩

- While amidst the (endless) process of editing this essay with a machete, Kevin Kelly posted What Books Will Become, a lovely meditation on the shifting form of the book. ↩

- It's not the density of the display, it's the effect of the canvas in which that display is wrapped; it's not the interface for highlighting, it's where those highlights live and what we do with them; it's not the units of measurement, it's the system by which we can universally and consistently point to any part of a text. ↩

- James Bridle looks at producing physical souvenirs from our digital reading experiences. Bookcubes: Souvenirs of Digital Reading, booktwo.org ↩

- It's true — the motivations behind asking 'How do we make books digital?' and 'How does digital affect books?' aren't necessarily the same. But then, it doesn't matter. 'How do we make books digital?' is, at best, a transition query. It's the low hanging question we ask as we try to make sense of industry-wide shifts. There is only one path to finding a true future form of the book, and that's abstracting the idea of the book from old publishing and consumption models. Dear friend Rob Giampietro reminds me of Clay Shirky's landmark essay on this very topic: Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable. ↩

- There are undoubtably countless examples of breaking Wikipedia entries, but on a deeply personal level, I was delighted and amazed by how quickly (and thoroughly) the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami entry appeared. ↩

- Part book design, part screen scraper script, part sculpture — On Wikipedia, Cultural Patrimony, and Historiography, booktwo.org ↩

- Signal vs. Noise ↩

- http://blog.frankchimero.com/ ↩

- Art Space Tokyo: An Intimate Guide to the Tokyo Art World, artspacetokyo.com ↩

- Kickstartup: Successful fundraising with Kickstarter and the (re)publishing of Art Space Tokyo, craigmod.com, August 2010 ↩

- http://robinsloan.com/ ↩

- Amada Hocking's Blog ↩

- I Love Typography, ilovetypography.com ↩

- http://www.pixelingo.com/ ↩

- Codex: The Journal of Typography, codexmag.com ↩

- The Domino Project, thedominoproject.com ↩

- And I'm not just talking about posting an essay on a blog. I'm talking about getting your book made — beautifully, cloth-bound if so desired. About getting your book on distribution and sales platforms that can reach tens of millions of readers (iBooks, Kindle, etc). About both the tools that allow for flat democratization of writing and publishing and also the tools that allow you to monetize it sustainably. ↩

- Softskull Books ↩

- Red Lemonade ↩

- Red Lemonade Goes Live, rnash.com, May 2011 ↩

- Amazon zaps purchased copies of Orwell's 1984 and Animal Farm from Kindles, Boingboing, July 2009 ↩

- Forever, A Working Library, January 2011 ↩

- Unless you're Jonathan Franzen. ↩

- Books in the Age of the iPad, craigmod.com, March 2010 ↩

- (This footnote intentionally left blank.)

- Commonplace Book, Wikipedia ↩

- The Social Life of Marginalia, Bobulate, May 2011 ↩

- Embracing the Digital Book, craigmod.com, April 2010 ↩

- Kindle Popular Highlights — not that I harbor any delusions that my essay had anything to do with this feature release, but it was nice to know we were on the same page at the same time. ↩

- http://openbookmarks.org ↩

- It will be an interesting field to watch how highly specialized books — in terms of interface, interactivity and design specificity — like Our Choice by Push Pop Press evolve in the coming years. ↩

- Threepress — A leading ebook software and consulting group ↩

- Ibis Reader ↩

- Inventing Books, robinsloan.com, May 2011 ↩

- Any author can indeed publish their own work but not all authors will have the resources, time, energy or just plain desire to become a publisher. There is talk of diminished value of publishers in the face of digital books, but the reality is that publishers are as necessary as ever. However, their roles have shifted. Their value lies as community builders, curators and editorial advisors. Not just deep-pocketed gatekeepers and financiers to the mythical land of printed matter, national distribution systems and physical shopfronts. ↩

- Onward: If it's not networked, it's not so great. I think we will continue to see a general decline in the exaltation of printed matter. This is fine because most of what's printed is printed poorly. The effect of networked capabilities on our reading experience will be (is, already, really) so powerful, that the only reason to seek the printed edition of something will be because it's been supremely well produced. Or that, simply, a digital edition doesn't exist. ↩

- Distributing a physical book is one of the most costly, time consuming and heart wrenching parts of publishing. So many lost and damaged books. So much energy and jockeying to get front-placement in shops. ↩

About the Author

Craig Mod is a writer, designer, publisher and developer concerned with the future of publishing & storytelling.

As of October 2010, he's based in Palo Alto working with Flipboard.

He is the founder of publishing think tank PRE/POST, co-author, designer and publisher of Art Space Tokyo and a startup mentor with 500Startups. He lived in Tokyo for almost a decade and speaks frequently on the future of books and media. He is the worst speller you will ever meet.

An extensive collection of images of books he's designed is available here.

Thank you

For their editorial slaps and prods: Rob Giampietro, Frank Chimero, Peter Collingridge, Carolyn Wood, Marcos Weskamp, Ben Henretig and Enrique Allen.

Copyright

All images and text © Craig Mod, 2011.

This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike license. If you wish to use reproduce any of this context in a commercial context, explicit permission is required. Please contact me directly.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License.

Where this was written (Marginalia for Me)

Everywhere. My God, this essay has been a work-in-progress forever.

Written at Tea Time, Cafe del Doge (best espresso in Palo Alto), Cal Ave Starbucks and Joanie's Cafe. On the top row of CalTrain up into the city, room 1725 at the Omni, The Mandarin Oriental, The Grove (Hi, Cassie!) in Pacific Heights, Samovar Tea Lounge, Ritual Roasters and The Summit.

On flights to New York, flights to Rio, flights to Buenos Aires and back. In the Sheraton on Times Square, a skinny hotel in Santiago, Chile, and the Hotel de las Americas in Buenos Aires. In a variety of Buenos Aires cafes, notably the one with the beautiful window in SOHO flanked by Romaine and Papadimitriou.

In Tokyo at the Tatami Room, at the Osborne residence leisurely about the couch, while escaping radiation poisoning on the Shinkansen to Kyoto. On a high floor of Hotel Granvia above Kyoto Station looking out over the shockingly placid city. In a Gion tea house.

In Tryon, North Carolina, on Newmarket Road and at the only cafe in town, waiting for Bill the lawyer. At TJ's Diner. In Saluda at the Purple Onion. In Hendersonville at Black Bear Coffee. In Asheville — lovely Asheville — at Malaprop's Bookshop and Cafe (until that interruption) and Dobra Tea Lounge (Chinese green tea).

And of course siting here, at this kitchen table, in the blue dining room at the Blue Shala.