Photos and Words and Teju Cole's Golden Apple of the Sun

Containers matter; what makes Teju Cole's latest book so great

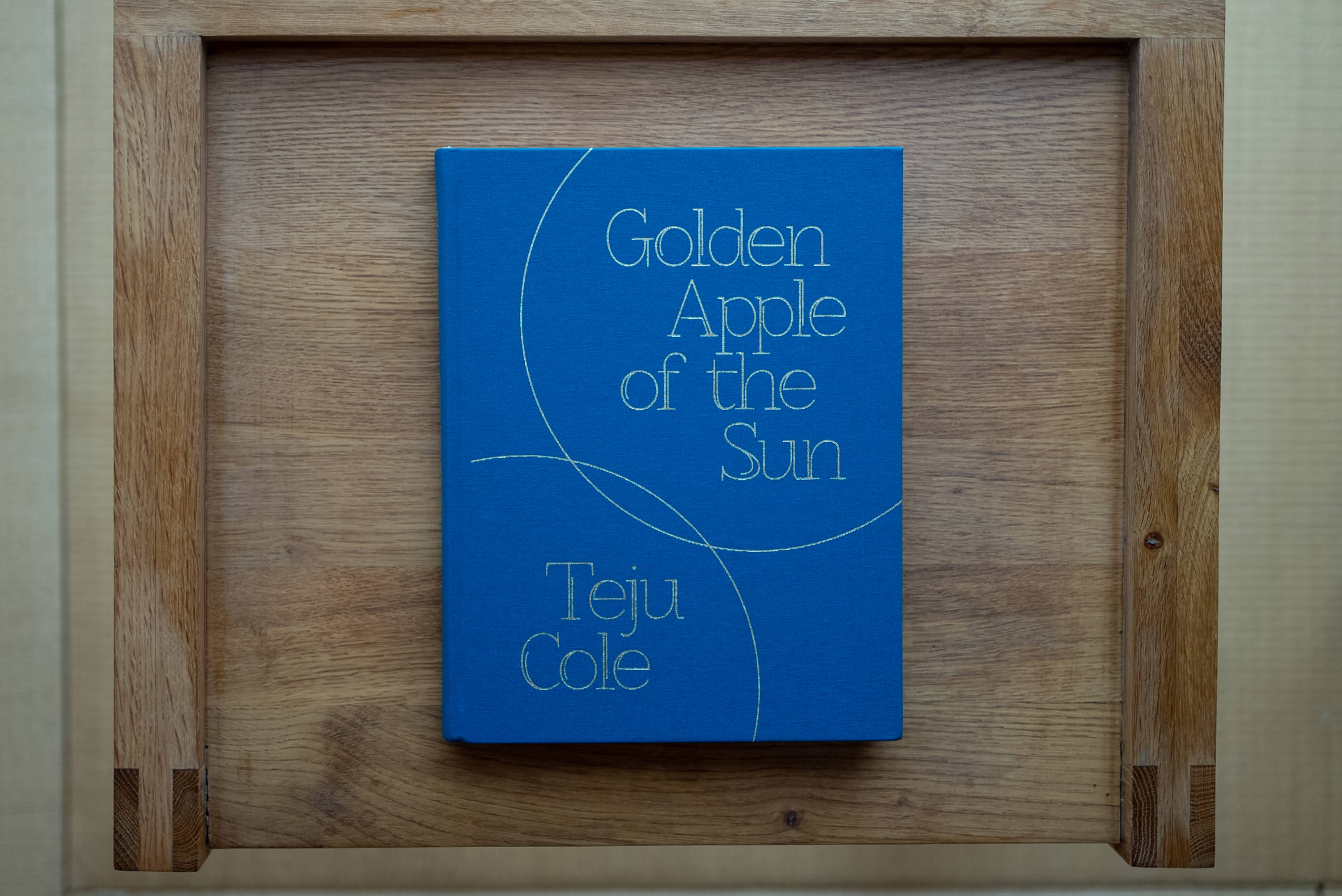

The more time I spend with Golden Apple of the Sun (MACK, 2021), Teju Cole’s newest photo+essay book, the more I adore it: the size (bit smaller than A4), the weight (650g), the binding, the cloth — its blueish color and slippery feel — the golden foil stamp of intersecting circles which read as abstracted kitchen plates and pans (or, as you come to think by the end of the book: lives, or lines about which items and humans for sale are to be inscribed). And that’s just the outside.

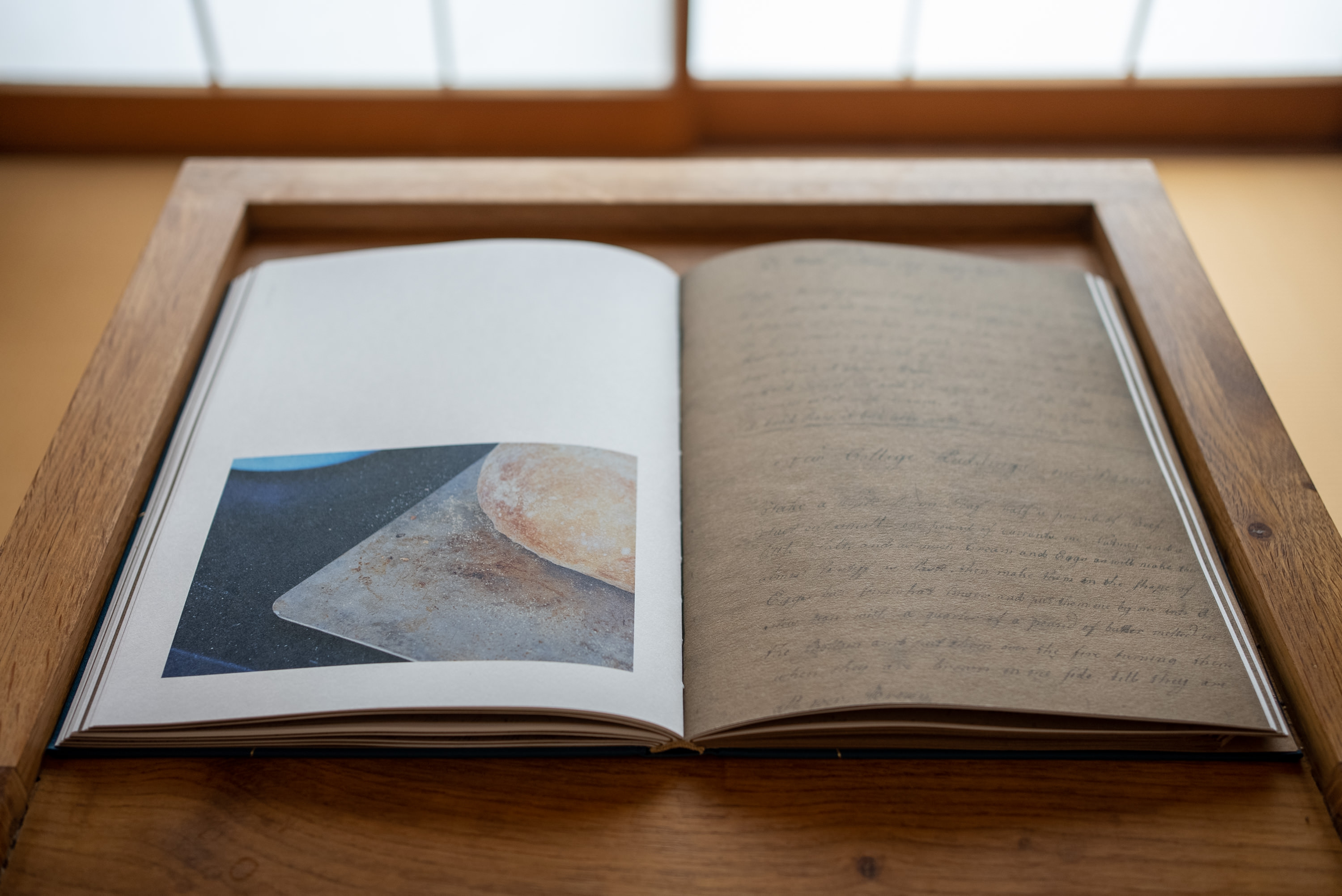

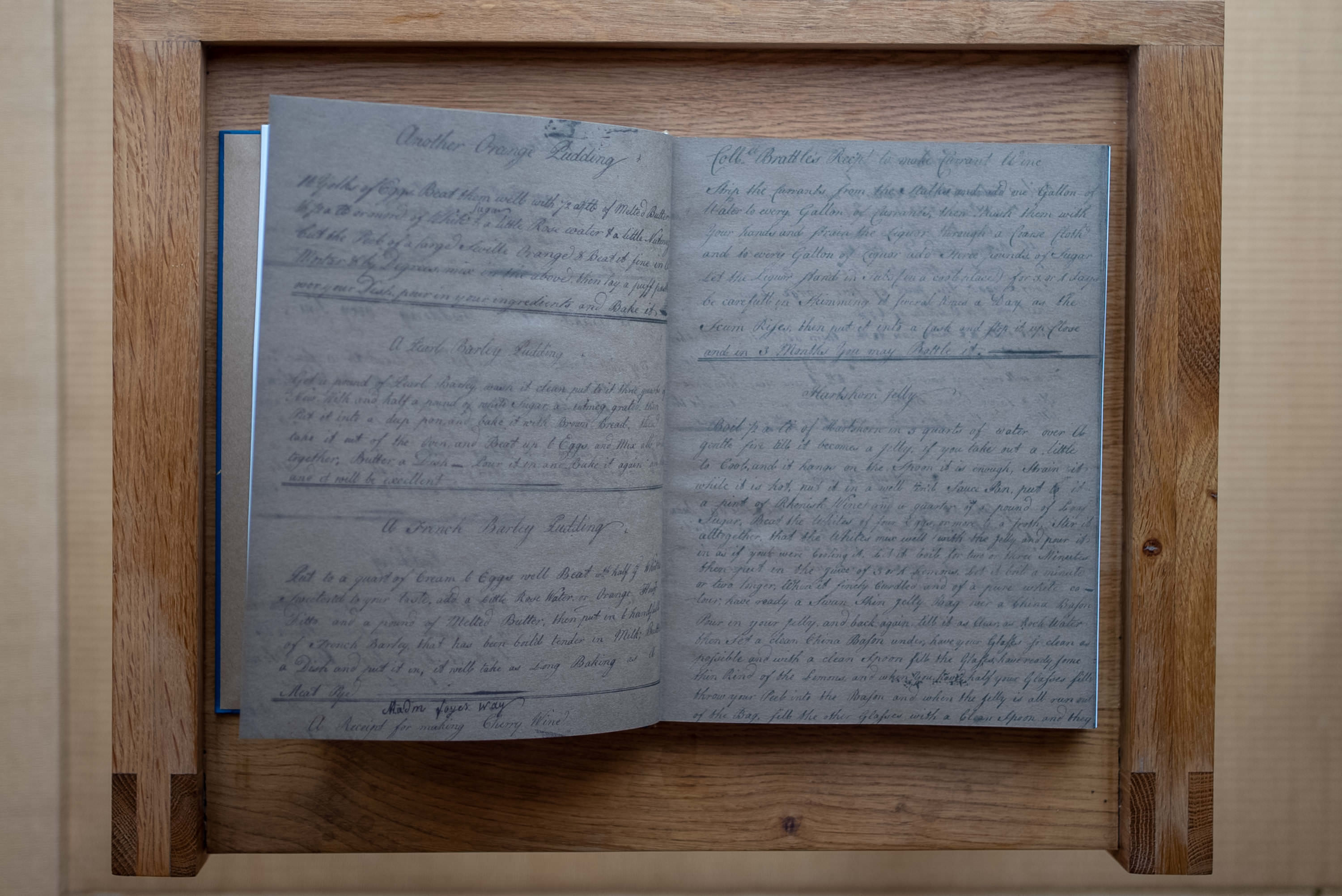

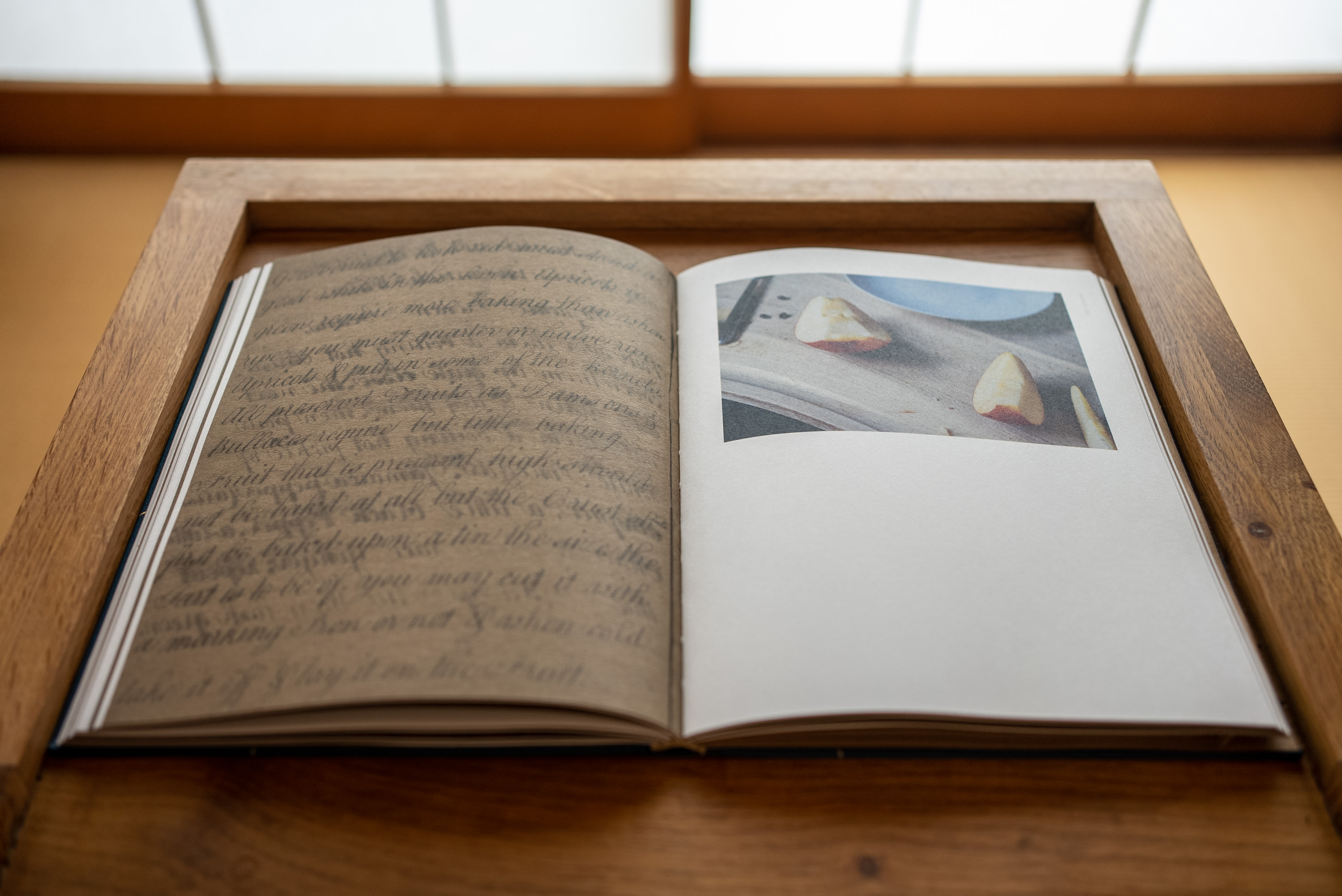

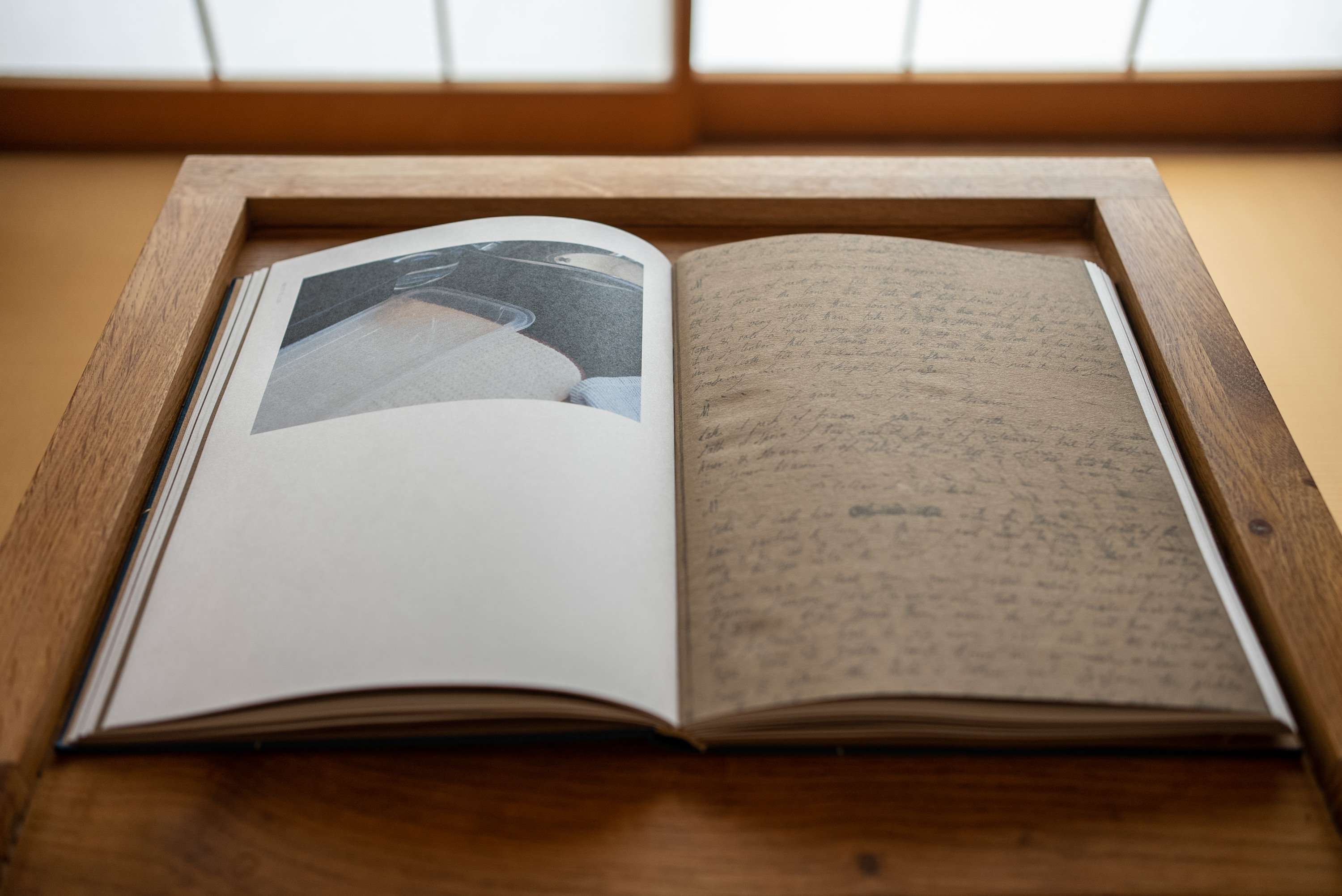

Inside, the body block: A mix of matte and craft paper. The chosen matte papers give the photos a floating-world quality — both in the way they don’t entirely resolve due to ink saturation (a matte paper quality I love), and that the subtle coating makes them feel suspended somewhere between the page and your fingers. In other books the craft papers would feel like an intrusion,1 but here they work. Upon them are printed enlarged reproductions of a eighteenth century handwritten cookbook, the seemingly atemporal, phantom object that Golden Apple of the Sun is in conversation with.

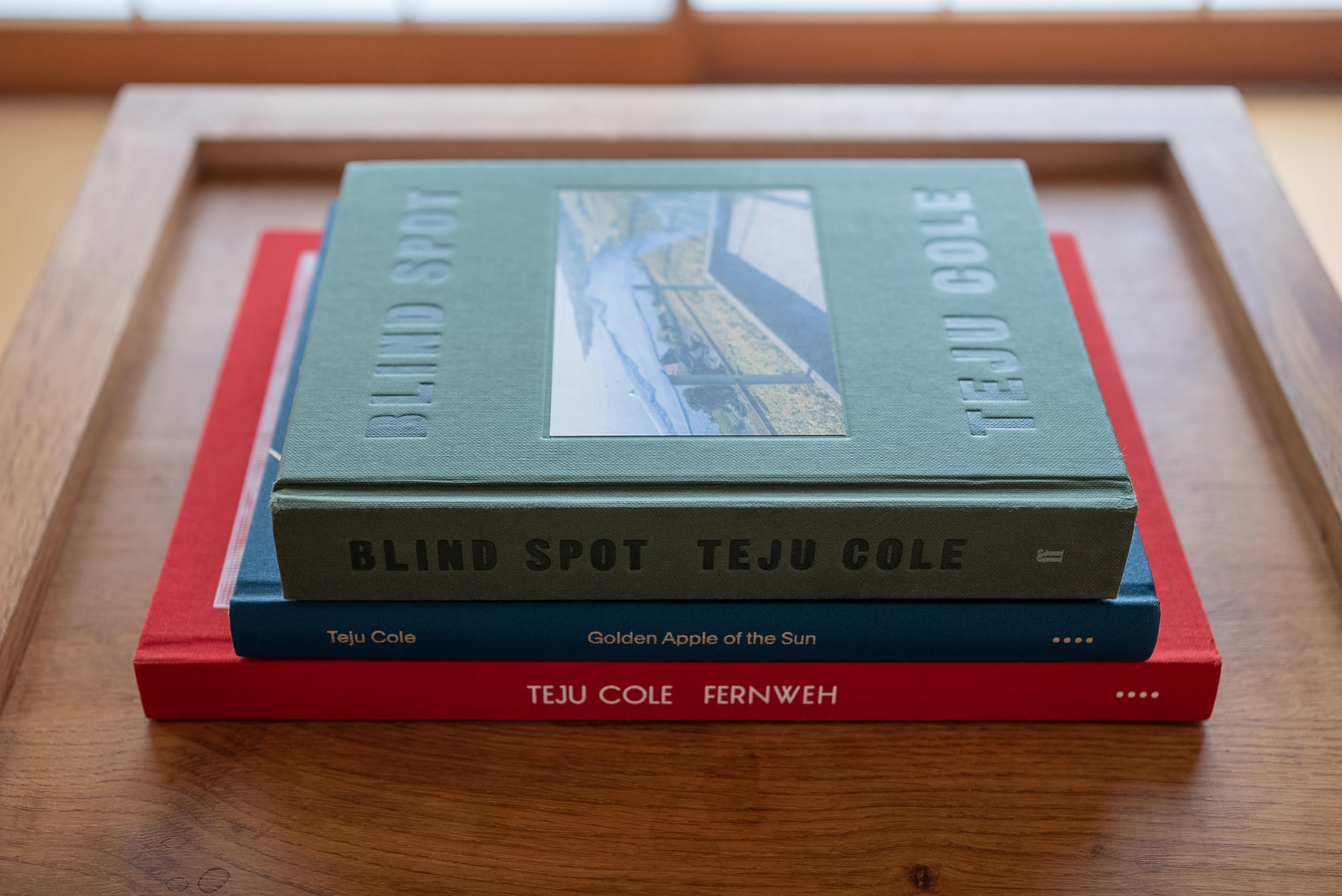

Blind Spot, Fernweh, Golden Apple of the Sun

I find that to best understand Golden Apple, it helps to look back at the other photo+essay books Cole has produced over the years.

As much as I enjoyed the writing and images of Blind Spot (2017, Faber & Faber), I had trouble parsing the object — the size felt off (too jagged, pointy, small, heavy), the paper choice wrong (too thick, too glossy (contributing to the issues of hand-feel)), the typography felt two revisions away from finalized (the font too attenuated considering the amount of text, the grey of the text blocks too light), the printing quality sub-par (low-resolution duotone). I don’t mean to be a fusspot, but I remember how disappointed I was in the object, and how that sub-optimal form2 made it all the more difficult to lose myself in what Cole had to say and show — which was substantial and fascinating. I still recommend the book, but recommend tempering your expectations around the object.

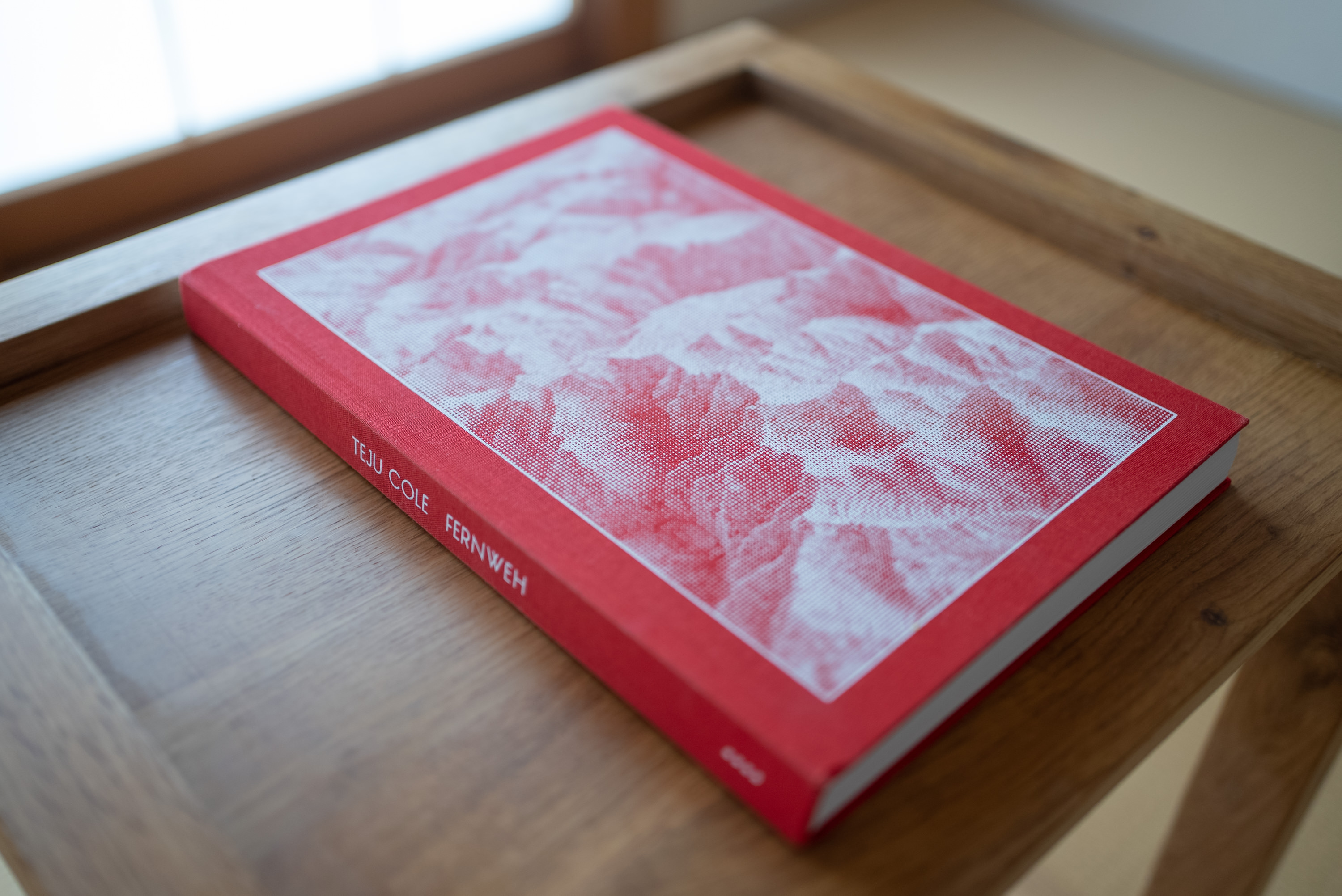

Fernweh (2020, MACK), gets closer to finding a platonic design ideal for Cole’s work. Designed by Morgan Crowcroft-Brown, her sensibility in material selection, typography, and image placement is plainly visible throughout. Fernweh also moves production of Cole’s books to Italy, and with that comes a marked bump in quality, immediately visible: from the tight binding tolerances between the flexi-bound cover boards and body block (a half-millimeter or so; probably handbound?), to the paper quality, to the resolution of the images (roughly double that of Blind Spot and printed with what look to be much higher-grade inks; night and day!). I remember unwrapping Fernweh and gasping, which is what you want a book to make you do — gasp a little on first contact. The silk-screened mountain-abstraction in pure white atop red cloth, no words, no names, is one of my favorite covers of the last few years:

In this way, Fernweh is the opening act to Golden Apple of the Sun, also a MACK publication, also printed and bound in Italy using fine materials.

Also, critically — it should be noted — designed by Morgan Crowcroft-Brown. This two-for-two designer × author relationship feels healthy, and I hope it continues! Golden Apple feels (to me) like Cole’s most successful photo+essay book-as-object book yet.

If Blind Spot was Cole formalizing his interest in pairing images with text (we see hints of this curiosity in his first/second (depending on market) novel Everyday is For the Thief (Faber & Faber, 2014)), and Fernweh is Cole stretching the rubber band of poetics and abstraction to some edge — of feeling out the possibility of photos+essay or photos+words, how diptychs and sequence modulate emotion — then Golden Apple of the Sun feels like Cole catching an eephus he threw out nearly a decade ago.

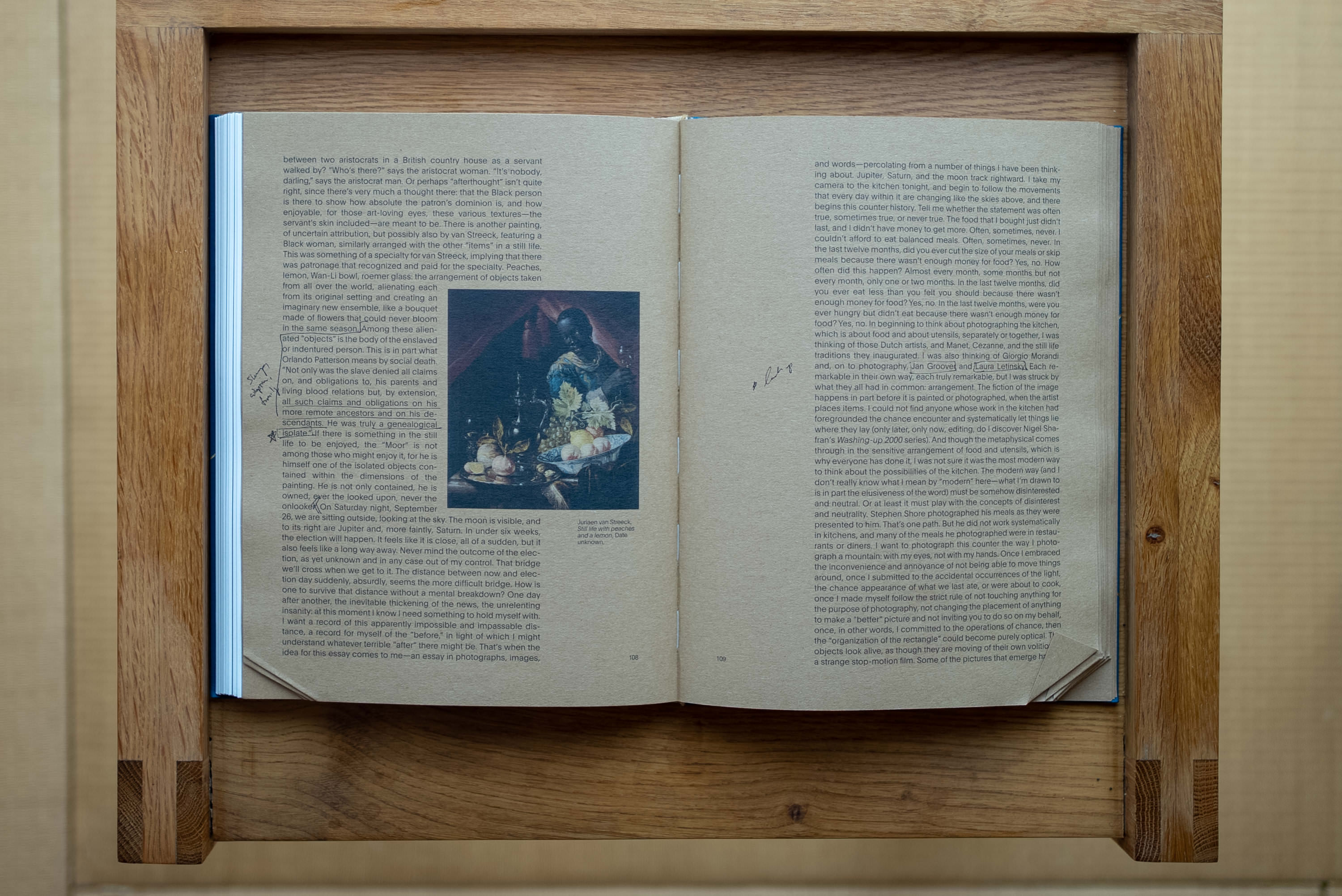

The beating heart of the book is the extended epistolary essay in the back, laid out in one giant paragraph over the course of some twenty-six pages, with generous margins (which you’ll want, for taking notes and responding), very much in the voice of the narrator of Cole’s novel Open City (Faber & Faber, 2011) — associative, academic, reserved, and yet surgical in revealing biographical information. The essay pivots around two thematic pillars: still life painting, its history, what is or isn’t revealed in the still life, what the image in that moment knows or doesn’t know and what we — looking back on it — will come to know or see only later; and a Boston cookbook from 1780, written in three hands across four parts, where the ingredients and recipes contained therein and the people who may or may not have written them are interwoven with the trafficking of humans. Between all of this, Cole weaves personal stories of hunger — literal and spiritual — religious conversion and un-conversion, and past lives in Nigeria and Cambridge.

“I remember this little child who was and wasn’t me forming a wish — the kind of wish one has in extremis — of never wanting to feel that hungry again,” Cole writes about being hollowed out in his youth. “The year of that Italian meal was the year I became aware that I had depression,” he writes some pages later. We are reminded that “Louise Glück has written that poetry is autobiography stripped of context and commentary; this statement is true of still life as well — how else could these few things on the table before us, arrayed against the dark, glow with such fierce warmth.” This text appears next to Juraen van Streeck’s “Still life with peaches and a lemon” and Cole reminds us: “Among these alienated ‘objects’ is the body of the enslaved or indentured person. This is in part what Orland Patterson means by social death. ‘Not only was the slave denied all claims on, and obligations to, his parents and living blood relations but, by extension, all such claims and obligations on his more remote ancestors and on his descendants. He was truly a genealogical isolate.’” As an adopted person, that phrase, “genealogical isolate” hits hard. It’s one of the more trenchant distillations I’ve read of the adopted experience, and is something I’ve never thought about before in the context of slave trade — compounded dehumanization through forced gene isolation. “A secondary meaning of ‘hunger,’ writes Cole, beyond the primary one of debility due to lack of food — emerges as early a the thirteenth century: to hunger is to have a strong spiritual desire … I will use my body, the hunger striker says, to show you a pain you know, so that you may begin to understand a pain you do not.” Which then: “But in Yoruba, we say ‘Mi ò mòó ie’: I don’t know how to eat this.” So much wiser than saying, reductively, lazily that you “don’t like” something. (How much of pain in the world is born from a reluctance to admit unknowing?) Youth feels typified by learning to eat the things of the other (those of our parents and then, older, of opening our palates to more distant cultures, frequently dazzled), the foods you don’t love, over time, becoming foods you do love, or at least understand. Reflecting on the photographic section of the book, Cole clarifies: “As I photograph, I’m looking for the moment when one kind of interest becomes something else, where the words I want are neither ‘interesting’ nor ‘boring.’” Photography then, becomes a tool for, perhaps, cultivating amazement? Cole writes, “At the Booker Prize ceremony in 1972, John Berger said: ‘Before the slave trade began, before the European dehumanized himself, before he clenched himself on his own violence, there must have been a moment when black and white approached each other with the amazement of potential equals.’” When we label people “old” we are calling out their ossification of amazement and openness. And when we talk about “being an adult,” we can mean the cultivation of an emotional and intellectual curiosity manifesting in a number of hungers. I feel like my own development as an adult is traceable through culinary epochs and leaps and amazements, and, on reflection, I’m grateful to still feel challenged and thereby, sorta, young. Food — not only as challenge or window, but life or work itself: “‘This is my livelihood’ can sometimes be said, in Nigerian English, as ‘this is how I’m eating.’” Food is on Cole’s mind because he is home, stuck there, as we all were (as many still are, in 2021) in 2020. 2020, the year so many of us became more intimate with our kitchens. The kitchen, a portal for time travel and chemistry. “In 1790 … a Boston resident compiled a ‘cook book’ of some eighty pages. The recipes, in addition to numerous puddings, jellies, pies, cake, and meat dishes, also include home remedies: for ’the heart burn,’ for the making of ointments, for dropsy.” Some two centuries later, Cole begins to document his own kitchen with a Fuji digital camera, a few miles from where the cookbook was compiled. He shoots and cooks. All the while, the phantasmic journal looms: “I stare at these handwritings, feel their ghostly energy … The heel of a palm resting on a page, more than two hundred and forty years ago.”

There’s something ghostly about Cole’s book, too — his is a “fast” book, and I like it all the more for that. Photographed and written in October 2020 at the height of Pandemic Unknowing (Will the vaccines work? What will happen with the election? What further sacrifices are to come?), published less than a year after Cole began working on it (Will the vaccines work on Delta? What will happen with Afghanistan, the climate? What future sacrifices are to come?), there’s a strange immediacy that you normally don’t associate with book-books in general — and certainly not photo books like this. It feels of the moment — like a digital thing, though it sits in your hand in refined physical form. That dissonance of the extreme nowness of the narrative and the timelessness of the object itself is something I’ve yet to see executed this well. Most “books of now” suffer from a lack of refinement. But I suspect Cole has been building up to this through his past work, and, in a way, much of this book was waiting for him each morning in the kitchen to pick up, to make note of, to photograph.

As for the images, there’s nothing sentimental about Cole’s photographs, they are simply studies in light and form in a home kitchen, tightly framed, shot with a kind eye, printed with softness. The images are both idyllic and of a documentary nature — here was my kitchen on this day (the days printed in grey type, vertically, respectfully, next to the photographs), they seem to say. Nearby, many years ago, three people took note of the recipes of their life, and here, today, Cole documents an array of cheese graters and freshly baked breads, three lemons, used plates and spoons, water spills and rags. Every single photograph is framed in landscape orientation (and a few that traverse the gutter seem to be cropped to a more square-ish ratio), and thoughtfully arranged within the rectangle of the page. They’re beautiful, and there’s more than a few I’d like to hang on my wall.

I think Golden Apple of the Sun doubly succeeds thanks to the constraints of how it was produced — pop-up, time-boxed, a work of seasonality — and maybe would have lost its way given more time. I strive to be more capable of this in my own work — working in seasons to override my own bad habits, to get books and projects out of the theoretical into the indelible now.

Golden Apple rewards multiple readings. There’s the initial paging through — which for me featured a kind of discordance or atonality between the photographs and the cookbook-printed craft paper. I was suspicious: Like, does this make sense? Did the book earn these design decisions? And, yes! That atonal setup is then resolved via the essay in the back, sprent with hints. Squint just right, and unexpected and spectral harmonies are revealed. I began to feel a freaky metempsychosis between the cookbook discussed within and the book in hand. It’s a satisfying and haunting cycle — the setup, delivery, the imbrication, and then return to the start.

Like I said, the more time I spend with this book the more I adore it. I purchased it upon release in July, and I dove back in soon after my second vaccination shot, to which I had an extreme reaction, and was thrown into a psilocybin-like hallucinatory state. So, perhaps I’m insane. Also, I’m biased, as I’ve been a fan of Cole’s work for years. But Golden Apple of the Sun reaches — within the Cole oeuvre — a new level of distillation of vision, and I love what he and Morgan Crowcroft-Brown and the printers and binders in Italy have achieved. It’s a gem, polyhedral, vibrating in its own fuzzy space where one kind of interesting becomes something else, handily earning its place among things known and strange and wondrous.

#Noted

-

Or overindulgence — one of the biggest “mistakes” I see in book design work is simply using too much: too many foils, too many stamps, too many types of paper. It speaks to the skill of the designer, Morgan Crowcroft-Brown, that she’s able to mix these papers so well. ↩︎

-

It may seem petty to hark on about design flaws, but you must believe they matter. Margins very much matter, and a piece of text or set of images worked over by the author or artist absolutely deserve the best possible platform — one that, ideally, disappears and allows the reader to be lost in the work. I found myself constantly aware of Blind Spot’s container. ↩︎