Ridgeline subscribers —

A little over a hundred-and-one years ago, on September 1, 1923, Tokyo shook. Well, all of Kantō shook. Especially Yokohama, which shook something extra terrible.

Since the start of the Meiji Restoration (1868) Tokyo has been reconfigured a few times. Ideologically / existentially by Perry’s forced opening of the country’s ports, the ending of the 265 years of (pretty peaceful) isolation. Later, during WWII, in the 1940s, when the Allied bombers carpeted the city in fire, reducing huge swaths of it to utter ash. And once again in the early ‘60s, as Tokyo prepared to host the Summer Olympic Games (sanely run in mid-October back then, not August, not during demon-heat in the name of advertising bucks and American football scheduling (I digress, I digress …)) — bulldozing the old, upgrading trains, removing trams, covering canals, and casting the city in a crisscross of elevated highways that continue to besmirch and chop up neighborhoods, cover important landmarks (Nihonbashi), even to this day.

But the 7.9 quake in 1923 — the biggest non-human-catalyzed reconfiguration — came just as the country was in full-modernization swing, and just before it got swept up in the hell of the second world war. Wright’s Imperial Hotel had just gone up, and then got smacked around. (It was damaged but stood, and would be torn down decades later because of that damage.)

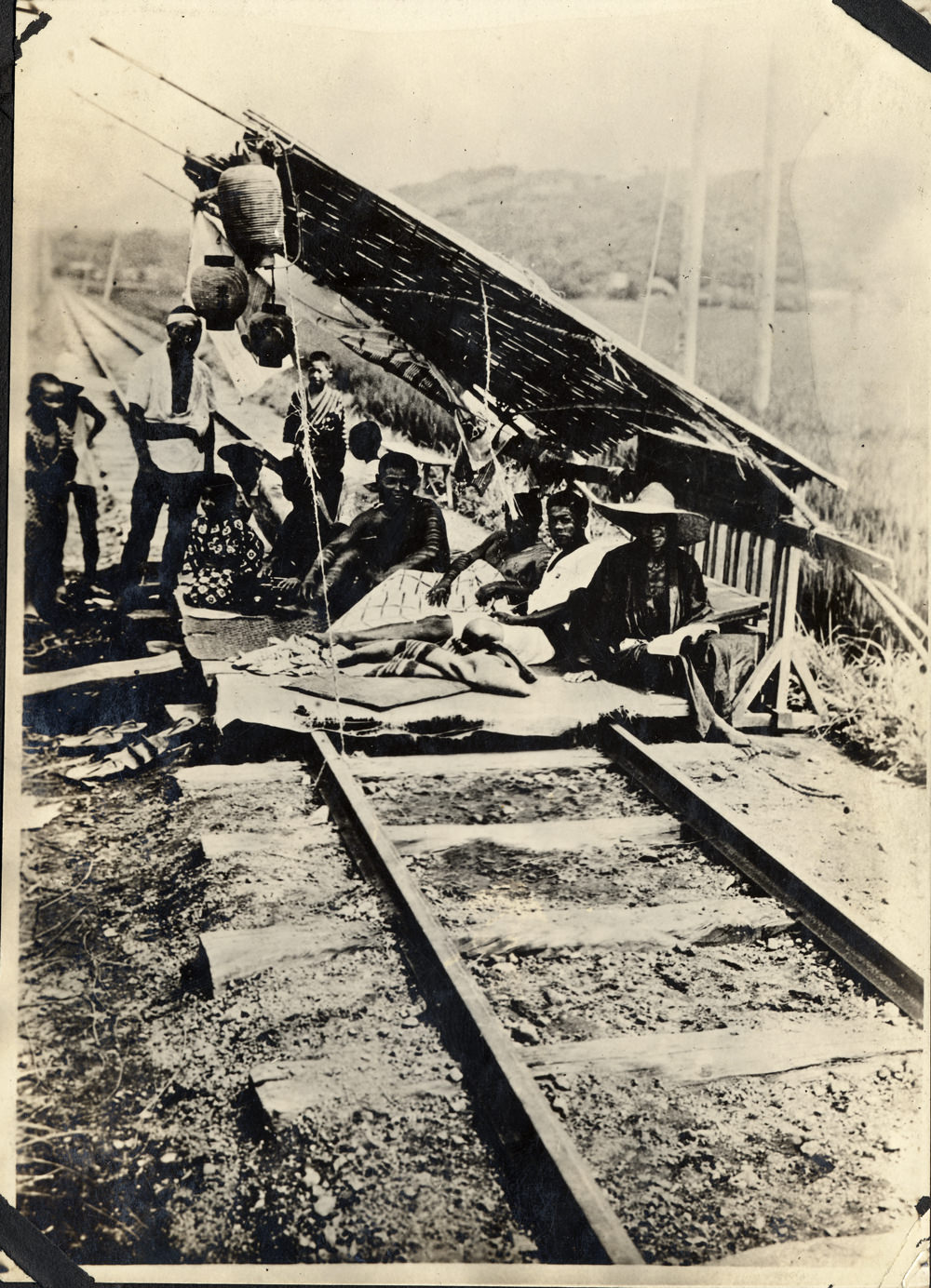

Journalist / author Henry W. Kinney (a man curiously without a Wikipedia page) was there during the quake, train-bound for his seaside home in Kamakura. The trains stopped. He got out, and relayed his first person (incredibly privileged and lucky — look at the photo at the top for a more generalized experience: impoverished refugees fleeing the Ueno area with everything they could hold) account in some spectacularly (distractingly) purple prose: “Earthquake Days,” The Atlantic, January 1924.1

There’s a lot going on here as a historical document. Germane to this newsletter, Kinney walks from Ōmori to Kamakura, which is a walk I’ve done several times now: on my way to start the Nakasendō in 2019, on my way along the Tōkaidō in 2020, and again, recently, in reverse, walking the Tōkaidō once again in May. You can see, Ōmori is barely out of Tokyo proper, just south of Shinagawa. It’s a big walk (“the seaside resort thirty-six miles from Tokyo”) from there to the sea.

We got out on the tracks. The inhabitants of Omori, a suburb of Tokyo, were flocking out on the right-of-way, seeking the safety it afforded from falling debris. ‘No wonder we can’t go on.’ The Englishman pointed to the track in front of us, the rails shimmering with snake-like undulations in the sunlight.

I’ve crossed the Tamagawa many times, but not like this:

The Tamagawa River, which divides the two prefectures of which Tokyo and Yokohama are the principal cities, formed also the dividing line between the two distinct phases of the disaster. Behind us, Tokyo suffered shocks of far less severity than those which devastated Yokohama, the principal damage being wrought by the fires which, immediately following it, swept devouringly through the capital. Yokohama, on the other hand, was smashed, utterly ruined by the shock. The flames merely reduced ruins to ashes, brought death to those who had been wounded or lay pinned under debris. Throughout the entire stricken area strange pranks of the quake had left some localities relatively unpunished, while others, scattered among the former, were flattened and shattered. It seemed as if the movement must be wave-like, smiting with greatest force the points touched by the crests of its billows.

The massive buttresses supporting the railroad bridge across the Tamagawa had been twisted, rocked out of place, and the tracks hung fantastically suspended between them. Oddly, a slight foot-bridge, formed by two widths of boards, was almost intact. We hurried across, the one thought in control being: what if another shock should catch us while on this bridge?

We had to jump from the bridge to the embankment. It had sunk, split, and shattered, one set of twisted tracks being more than six feet above the other.

Kawasaki was destroyed. And Yokohama was absolute death (“It seemed impossible that any inanimate manifestation of nature could be so insanely malicious as was the shock which smote Kawasaki, a large village just on the Yokohama side of the river.”) — it was the fires that mainly did the damage and magnified the carnage (as is often the case in these things).

Buildings were rubble:

On the right was a mound of bricks, a huge, confused pile, with great beams and splintered wood protruding haphazardly – the remains of the greater part of the Meiji sugar factory. Beyond it, the remainder of the building was wrapped in flames, seething up toward the top story, where, exposed, it seemed almost indecently, and stripped of the walls which had hidden them, stood three vacuum pans, great boiler-like affairs, as if disdainfully unconcerned with the destruction creeping up toward them. Farther on was the large square ferro-concrete building of an electric-light plant, one side smashed in, but still holding together, resembling a battered pasteboard box.

Kinney’s research for the story seems scant, to put it mildly. So the most important contributions he brings are the first person accounting of what others were doing, how others were faring along the road. They stop at a still-functioning shop:

Kirin beer; was that all right? It was not very cold. She was very sorry. Now, where was the opener? She hunted about in the confusion, showing more annoyance at the disappearance of the trivial instrument than at the other consequences of the disaster. Finally she found it, brought glasses, served us, with the usual courteous phrases. And the price was as usual, forty-five sen. In the course of my long wanderings throughout the devastated area, on that day and on those following, I saw or heard of no instance of profiteering among the common people. Even the last bottle, the last candle, the last bit of fruit, were sold at ordinary prices, even before martial law made profiteering an offense. It was not thought of.

Kinney’s shock at the “humanity” of the Japanese is a classic reporting quirk of the time. You see this often in reporting on Japan: “The stoic Japanese” taking disaster in stride. This is hardly a uniquely Japanese phenomenon, and often stinks of armchair anthropological othering. Obviously of a slightly different ilk, but even NYC — a place everyone seems to imagine devolving into total chaos and Mad Max carnage at the first opportunity — has peacefully and playfully and dare I say, stoically, sans-profiteering, gotten through terrorist attacks, massive flooding, blackouts, and other disasters in the last few decades.

Again, most interesting in Kinney’s notes are his direct observations, what people were carrying for example:

Finally we were forced back to the refuge of the railway tracks. There they sat, the inhabitants, in groups, each family guarding the household goods which it had snatched up in flight. Futon, padded quilts, predominated, but all manner of other goods might be seen, even shoji, the latticed paper-covered doors and windows, and chests of drawers.

And he can’t but help “decode” the natives for western readers, legible only through, of course, a common phrase:

The quietness was striking. There was no wailing; they conversed in low tones; but generally they sat silent, staring at the destruction. One admired their stoicism, the spirit which had made the shikataganai, ‘it can’t be helped’ phrase, almost the Japanese national motto. There was no confusion, no crying out; even the children were hushed.

In the background though, there wasn’t a lot of stoicism going on, there was actually a whole lot of murder of Koreans happening: the Kantō massacre. Lynch mobs roamed. 6,000 ethnic Koreans were slaughtered by police, military, and vigilantes. In present day Noda City, the Fukuda Village Incident took place. Kinney notes this briefly:

In the meantime Koreans were slaughtered right and left. Crowds killed on sight, frantically, any Korean whom they might find.

It was so bad that folks did anything they could to explicitly identify as non-Korean (although I’m not sure why Koreans also couldn’t just do the same):

The day after the disaster the servants insisted on tying red bands about our arms. Everyone wore them, Japanese and foreigners. It was a badge of rectitude, to protect one against the vengeance which was being visited on the Koreans. That was one of the most cruel phases of the days which followed—the blind, unreasoning hatred of the Koreans, of whom thousands had been employed as laborers. The report went about that they were committing incendiarism, arson, and rape, that they were poisoning wells, that they were in league with Japanese anarchists to make use of the situation to overthrow the existing order of things. No doubt, some of them became looters. A friend saw some engaged in looting in Yokohama—but Japanese were guilty, also.

But the walk continued on, just west of Yokohama:

The buildings had collapsed exactly as if some huge pressure had suddenly been applied on the rooftrees, squelching them down flat, walls bulging out from under the eaves, or throwing them to one side. Frequently the streets were blocked where roofs from both sides had encountered each other in the middle of the thoroughfare. Progress became laborious. One climbed over the roofs. In the first village, Hodogaya, nearly all the houses were down; but here also the inhabitants were calm, stoically poking about in the ruins for pots needed for water, material for construction of temporary shelters. Many such were already up. One saw in them families. They had almost an air of repose, contentment, as they sat there, conversing, eating, children playing with toys contrived out of the flotsam of destruction.

Shops that remained functional continued to operate in good will (again, I think you’d find this in any other country experiencing disaster; but the details are worth quoting):

We stopped at a partly ruined shop for a drink. There was no more beer, but would we have tea? A hibachi (fire-pot) had been saved, on which a kettle was gurgling peacefully. The woman prepared the tea in tiny handle-less bowls. Her husband produced zabuton (small cushions). Would we deign to be seated? The same pleasant courtesy as ever. No, of course, they would take no money for tea, just tea. And we must take along some cakes for the journey. They forced them upon us. Of course, they would take no pay. Good-bye, good luck.

Onward they walked. The smoke from the fires of Yokohama reduced visibility. In the distance, someone with a lantern was leading a group south, towards Kamakura:

… but ahead all was blackness, punctuated only by the twinkling light of a paper lantern, dancing in front of us like a firefly. We caught up to it. The bearer was a burly Japanese, competent, one of the few Japanese who seemed to have a sense of leadership and organization. He headed a small caravan of about a dozen—men, a few women, and a couple of children—plodding along behind the faint glimmer. Might we join and benefit from the light? If course. At once they made a place for us, insisting that we take the best one, immediately following the lantern-bearer. So we crept on, slowly. Where the road had been demolished by cracks, the leader stopped, holding his light high. ‘Abunai’ (look out). Precariously we would advance, often creeping on hands and knees from floe to floe—it seems the only word—of earth. We gained the railroad track, but it was little better. Embankments had slid into the rice-patches, leaving tracks and ties suspended in mid-air, swaying as we crawled over them in the darkness. The women and kiddies came along bravely, needing little help. There was no word of complaint.

Ofuna today is a pretty hefty railroad hub. I’ve walked through it / past it many times. Here’s what Kinney saw:

The Ofuna junction station was in ruins, but on the tracks between the wrecked buildings the train officials had formed a sort of relief station. They brought water and insisted that we lie down on blankets which they had spread over the ties between the rails. But there was no rest. The Ofuna people had news of Kamakura, only two miles away. The shock had been bad there, hidoix (terrible). The whole down had been smashed flat and then had burned. There was nothing left. We hurried on. As we came out of the long tunnel through which one enters hill-guarded Kamakura, we saw a few detached houses—flat; beyond them a wide area of flame, licking the ground far and wide. Most of the town had been consumed and the fire was now only playing over the embers.

Kamakura was also flattened, but his seaside home (probably around Yuigahama, though he doesn’t explicitly say) was mostly intact. And his son was unharmed — he had jumped out the window the second the place started shaking: “he had dived, mother-naked, into the shrubbery, without even touching the window-frame.” And was then cared for by their servants.

What a walk. This is a hard walk on a good day, never mind when you have to clamber over homes and bodies, when the air is thick with the smoke of death.

Foreign aid came, but it took about five days (which seems fast!) to arrive from China:

The principal shock had occurred at noon of Saturday, September first. On Tuesday we were relieved by the arrival of a Japanese destroyer—assistance, finally. On Thursday relief came—American destroyers, a flock of them, which systematically scoured the entire coast section, taking off refugees, foreigners, and Japanese alike. It was a point of pride with the Americans that their first relief ship arrived three hours ahead of the British; but both nations alike, British and American, steaming at full speed from China, brought relief before the Japanese fleet, lying in home waters, had contrived to do so. The prompt action and practical work of the foreign nations stood in sharp contrast to the general inefficiency of the Japanese Government. Where the Japanese people generally rose inestimably in the respect of the foreign residents, the hopeless incompetence of officialdom was almost criminal, and September first, 1923, will remain forever a day of utter disgrace in the annals of the Japanese navy.

Who knows what the Japanese government was thinking or why they acted as they did (certainly Kinney doesn’t; does he even speak Japanese?), so instead we focus on what he saw walking Tokyo:

I walked about and saw most of the official building section remaining. The great modern business quarter at Marunouchi had suffered but little, though crushed and, occasionally, fire-gutted interiors were hidden by walls which had been damaged only a little, and the impression of relative lack of loss was in part false. The extensive residence sections of the well-to-do and middle classes were largely intact. Stores were doing business, cars were running in places, and electric lights had begun to function. But vast areas near the principle centre of the city had been laid waste for many blocks. The great retail-business street, the famous Ginza, had been completely wrecked by fire; and as one went on to the poorer sections, the tremendous congested quarters of the laboring classes, of the poor, Honjo and Fukagawa, even the miseries of Yokohama were outdone. Fire had destroyed the buildings completely, and here one found the masses of the dead. These people had fled for escape to the open spaces, and the flames had hemmed them in; and even where fire had not reached them, they had been roasted in heaps of many thousands. In one place a mob of thirty-two thousand had been thus tortured. The naked bodies lay, twisted and contorted, naked or with only rags clinging to them, covering acre upon acre (NSFW). At places the jam had been so congested that they had not been able even to fall to the ground. So they stood there, packed, the dead rubbing elbows with the dead.

Finally, having seen enough, he hops the “Empress of Australia” from Yokohama to Kobe, and takes up camp in the Oriental Hotel. Thus, he caps the piece with an ending so satirical and of the moment, only an LLM could deliver such a thing with a straight face today:

In the lobby I met Mr. B.W. Fleisher, owner of the Japan Advertiser and the Trans-Pacific magazine, of which I am, or was, the editor. His entire plant was destroyed. He took me by the arm. ‘Come on, let us get out of here. This is what we must get away from, this continuous raking over the dead ashes. We must get busy — I have ordered a new plant already — all of us, especially us Americans. We owe it to Japan. The new Government has courage. It’s going to reconstruct on a vast, progressive scale—so we must forget our losses and lend a hand. America has a mission here.’

And that is the spirit of the Americans in Japan.

A pretty incredible, if flawed, document, making note of a harrowing walk immediately following the worst natural disaster to hit Kantō in centuries. Maybe I’m being too harsh on Kinney, but if you take these documents too seriously you’ll lose your mind, and miss out of the value they otherwise provide.

At some point there will be another one of these — a massive Kantō quake. And one hopes it won’t be like it was one-hundred-and-one years ago. If you do live in Tokyo, now’s a good a time as any to make sure your disaster escape pack is ready, and you’ve got extra supplies at home.

I’m deep in prepping Kissa by Kissa for its Japanese release in November. And finishing up the final touches on Things Become Other Things for Random House, to be published in May 2025.

More soon,

C

Noted

-

Photographs are from the Dana and Vera Reynolds collection, digitized and made public by Brown University. “In August 1923, William Dana Reynolds, with his wife Vera Hunt Reynolds and their young daughter Helen embarked from Honolulu on the Japanese steamship Taiyo Maru, bound for Yokohama. While at sea, the ship experienced and survived a tsunami only to arrive, badly damaged, in Yokohama Bay on September 8th as witness to the destruction caused by the Great Kanto Earthquake. Fully aware of the risks involved, eight of the male passengers decided to leave the ship and enter the city. Dana Reynolds was among them. For the next few hours, and later, upon his return several days after the initial quake, he recorded a series of compelling images of the horror and devastation.” ↩︎