Oh God, It's Raining Newsletters

Email: The oldest networked publishing platform

Email’s beginning was perfectly unremarkable: “QWERTYUIOP.” A keyboard burp. Something your cat might type. A nothing message sent by Ray Tomlinson in 1971 to test the system. But email has stayed, and has largely stayed decentralized, and from that — its ubiquity and lack of central authority — email has become one of the most boringly powerful publishing platforms around.

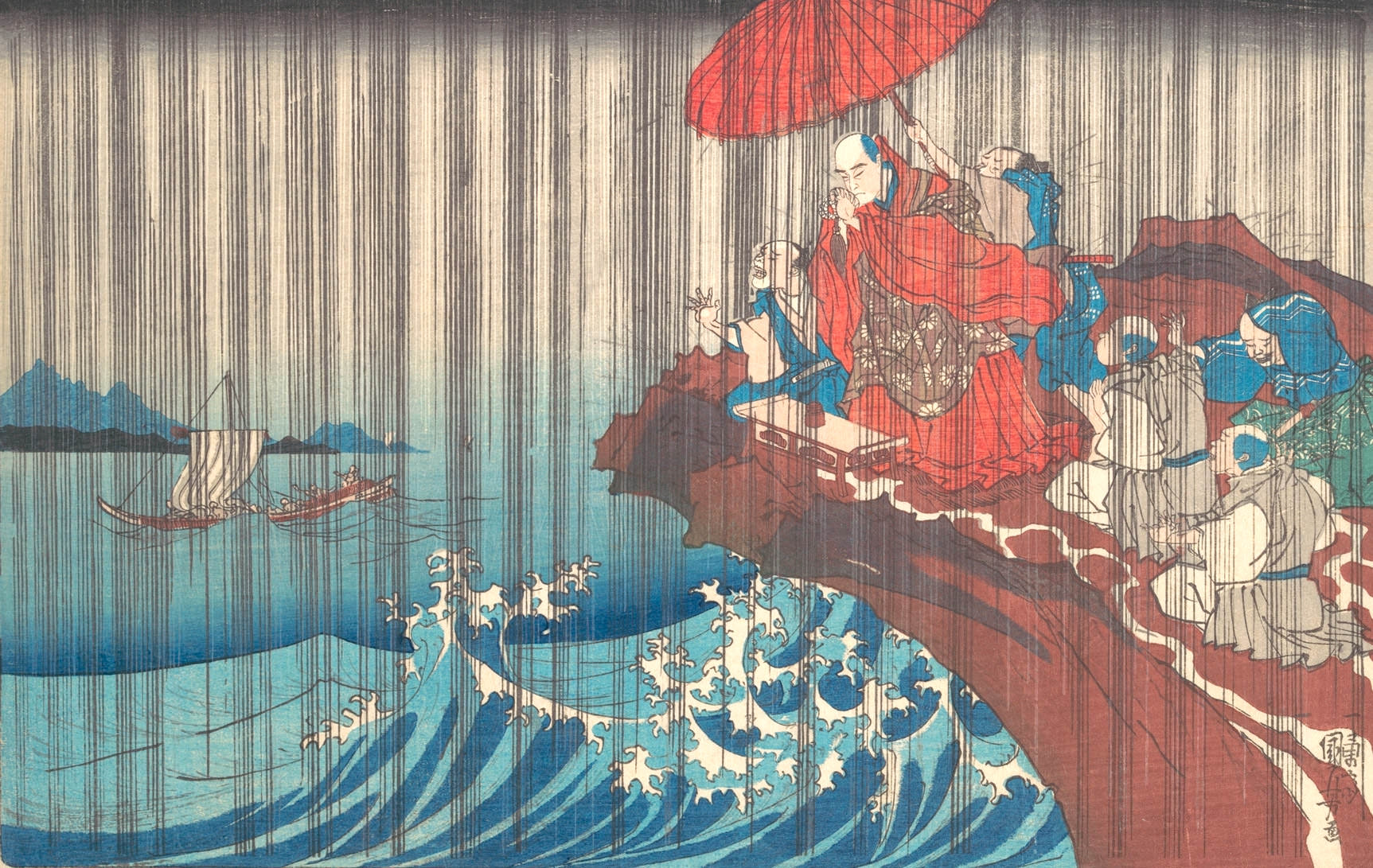

I fear we’re entering an era of newsletter fatigue, but a month ago I started a new one. It’s called Ridgeline, it’s about walking — the perambulatory, wandery version — through the mountains and old paths of Japan.

The newsletter is weekly, composed of a single photograph, and (usually, hopefully) no more than 500 words.1 It’s meant to be low-stress high-reward. An email you knock down in about a minute, scan quickly, mark as done. But I’ve written several of them so far, and I am incapable of abiding by these rules.

As to the primary topic: Japan has been my home base for the better part of my life, and I’ve compulsively walked bits and pieces of the country these past six years. I’m interested in the connection between this impulse and the boundless connectivity we’re all presently awash in.

But more broadly, launching it has given me reason to consider the state of newsletters and email, in 2019: Things are unexpectedly amazing.

Newsletters and newsletter startups these days are like mushrooms in an open field after a good spring rain. I don’t know a single writer who isn’t newslettering or newsletter-curious, and for many, the newsletter is where they’re doing their finest public work.

As for the present landscape of NAASes (Newsletter As A Services):

- Substack is the current NAAS darling, built from the ground up for charging subscribers a monthly or yearly fee.2

- Buttondown is a (somewhat) recently launched NAAS built by a very engaged developer, beautifully designed, that looks like it might be the new TinyLetter. Subscription integrations forthcoming (eating into Substack territory?). This is probably where I’d start if I were starting a public newsletter today.

- TinyLetter, founded in 2010, was the old darling that rekindled a general interest in the newsletter genre. It was quickly gobbled up by MailChimp in 2011, though, and has a somewhat uncertain future, so it’s tricky to recommend starting your newsletter on it today.

- Memberful is a generalized subscription service, but it integrates with most major NAASes, thereby allowing one to roll their own paid newsletter with a bit more flexibility, as Ben Thompson has done to much success with Stratechery. My own SPECIAL PROJECTS membership program and its attendant Inside SP private newsletter is powered by Memberful as well.

As to why the landscape now burgeons, I address that in part in a recent Wired essay:

One way to understand this [newsletter] boom is that as social media has siloed off chunks of the open-web, sucking up attention, the energy that was once put into blogging has now shifted to email. Robin Sloan [(Year of the Meteor newsletter)] in a recent — of course — email newsletter, lays it out thusly:

In addition to sending several email newsletters, I subscribe to many, and I talk about them a lot; you might have heard me say this at some point (or seen me type it) but I think any artist or scholar or person-in-the-world today, if they don’t have one already, needs to start an email list immediately.

Why? Because we simply cannot trust the social networks, or any centralized commercial platform, with these cliques and crews most vital to our lives, these bands of fellow-travelers who are – who must be – the first to hear about all good things. Email is definitely not ideal, but it is: decentralized, reliable, and not going anywhere – and more and more, those feel like quasi-magical properties.

Ownership is the critical point here. Ownership in email in the same way we own a paperback: We recognize that we (largely) control the email subscriber lists, they are portable, they are not governed by unknowable algorithmic timelines.3 And this isn’t ownership yoked to a company or piece of software operating on quarterly horizon, or even multi-year horizon, but rather to a half-century horizon. Email is a (the only?) networked publishing technology with both widespread, near universal adoption,4 and history. It is, as they say, proven.

#Minimize Instagram

That ownership of platform, putting edges around digital things — creating a well-defined unit, a package, something to be delivered — and of course the desire to share my walking-in-Japan experiences led me to launch Ridgeline as a newsletter. But I also felt impelled to minimize reliance on Instagram.5

Facebook has collapsed as a viable marketing / distribution platform for me. Twitter is fine, but the audience trends heavily to certain demographics. And as lovely as Instagram has been,6 with the loss of its cofounders in 2018, I feel like we are entering the Death By Monetization/Optimization™ spiral that Facebook is so very good at.

Part of what made Facebook a breath of fresh air ten years ago was its relative minimalism compared to MySpace, etc. Now it’s a full-blown space shuttle interface.

Repeat for Messenger.

And, now, repeat once again for Instagram.

Instagram will only get more complex, less knowable, more algorithmic, more engagement-hungry in 2019.7

#Weary bones

I’ve found this cycle has fomented another emotion beyond distrust, one I’ve felt most acutely in 2018: Disdain? (Feels too loaded.) Disappointment? (Too moralistic.) Wariness? (Yes!) Yes — wariness over the way social networks and the publishing platforms they provide shift and shimmy beneath our feet, how the algorithms now show posts of X quality first, or then Y quality first, or how, for example, Instagram seems to randomly show you the first image of a multi-image sequence or, no wait, the second.8

I try to be deliberate, and social networks seem more and more to say: You don’t know what you want, but we do. Which, to someone who, you know, gives a shit, is pretty dang insulting.

Wariness is insidious because it breeds weariness. A person can get tired just opening an app these days. Unpredictable is the last thing a publishing platform should be but is exactly what these social networks become. Which can make them great marketing tools, but perhaps less-than-ideal for publishing.

The desire is simply to publish photos on my own terms. And to minimize the chemical rewards for being anodyne, which is what these general algorithms seem to optimize for: things that are easily digestible, firmly on the scale of “fine, just fine.” It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the more boring stuff we shove into our eyeballs, the more boring our taste becomes.

And so here we are: leaning on an open, beautifully staid, inert protocol. SMTP as our savior.

#Silence

Here’s another, more subtle, point about the grace of email and newsletters: Creation and consumption don’t happen in the same space. When I go to send a missive in Campaign Monitor the world of my laptop screen is as silent as a midnight Tokyo suburb.9 I think we’ve inured ourselves to the (false) truth that in order to post something, in order to contribute something to the stream, we must look at the stream itself, “Bird Box”-esque, and woe be the person in a productive creative jag, wanting to publish, who can resist those hot political tweets.

#Good peoples

If I’m writing about newsletters, let me point at some that excite and delight:

- Joanne McNeil’s All My Stars — a catalyst that has led me to pick up a number of books that have enchanted to the moon.

- VQR’s Allison Wright’s I Don’t Hate It for similar reasons and fine writing.

- Warren Ellis’ Orbital Operations for making me feel like I am never working hard enough. It has also become an archetype of the rhythm of work work working and a real-time account of the writing life. (Without the slightest sarcasm or cynicism, it’s the closest thing to a … vlog … for writers as I’ve seen. (Sorry, Warren.))10

- Laura Olin’s newsletter — known for her Everything Changes newsletter way back in the yet-to-be-burning-world of 2015, Laura does the link-list format justice. And her Jobs Board at the bottom is a fine idea.

- Frank Chimero’s FTC/ETC which Mr. Chimero almost never writes but when he does makes the day a good day.

- Jenna Wortham’s fermentation & formation — rarely sent, but always appreciated, center-aligned prose poems.

- Clear Left’s Clearletter — a superb example of a company having a voice and giving you just two or three well-chosen industry-adjacent gems a week. (A good counterexample to the newsletters that seem to think volume of links is a virtue.)

- FSG/MCD’s Electric Eel for insight into what a publishing house can do with the format when they stretch out a bit and don’t just focus on the upcoming season’s list.

- Tim Carmody’s Amazon Chronicles — following in the paid-tech-commentary footsteps of Ben Thompson’s Stratechery. Tim very smartly ran a campaign to “unlock” the commons, to make the newsletter available for free for all if two hundred people signed up as paying subscribers. Well, that happened in a scant 24 hours. Tim’s newsletter is a great example of what extreme focus (Amazon Amazon Amazon) and clear intent gets you: bucks in hand.

This list leaves out a mountain of others — we are, truly, awash in great-writing-via-email — which brings us back to the top: Newsletters are having a bit of a moment.

But, why?! Why all this newslettering?

Aside from the sense of ownership and distance from social media, let me explain why I’m so attracted to them:

In parallel with my walking, these past six years I’ve written another newsletter called The Roden Explorers Club. And of all of my publishing online — either through this site or publications, on social networks, in blips or blops or bloops or 10,000 word digressions on the sublimity of Japanese pizza — almost nothing has surpassed the intimacy and joy and depth of conversation I’ve found from publishing Roden.

This intimacy — both from my side and that of the recipients — seems to engender a kind of vulnerability that I haven’t found elsewhere online. But the intimacy is not surprising: the conversation is one-to-one even though the distribution is one-to-many.

Years ago, I helped build a storytelling platform called Hi (a simplification of its original name: Hitotoki, now shuttered and archived) and one of the things I’m most proud of our team having concocted is the commenting system. We had tens of thousands of users and almost no issues with harassment. You could comment on anyone’s story and your having commented would be public — a little avatar at the bottom of the page — but the comment itself would be private. This allowed folks to reap the public validation of engagement (“Whoa! So many comments!”) while simultaneously removing any grandstanding or attacks. It wasn’t quite messaging. It wasn’t quite commenting. It felt very much like a contemporary, lighter take on email, and in being so was a joy to use. Here’s what the bottom of an entry looks like:

And so I use the word “intimacy” up above not in some dopey or saccharine way, but rather to signal a dropping of artifice we are often encouraged to project online. I would say Roden is not cool, in the coolest possible way. And the epistolary nature of email helps reinforce our shared humanity — the one-to-oneness — we so often lose on social networks.

From my end, this intimacy has profoundly affected what I’ve chosen to write about: Identity and multiculturalism, perfect laughs, meditation, great walks, artist retreats, and more.

Even though I also publish Roden on this website, there’s something about the framing of email — the inbox, that weird neither-here-nor-there networked space — that unlocks a permission to write about things I wouldn’t otherwise feel … welcomed? to write about. I don’t know where I’d pitch half of these essays, and when I start most of them, I don’t intend for them to go as long as they do.

Which is to say, my experience with the generalized nature of Roden has been so good11 that I wanted to expand in an even more deliberate and focused way. Hence: Ridgeline.

Annie Dillard’s “The Force That Drives the Flower”, written in 1973, is striking not only for feeling so epistolary (as is so much of Dillard’s writing; why it can hit the gut with such a thud), but also in how a passage like this, might have been lifted from her Tinyletter in, say, 2016:

So far as I know, only one real experiment has ever been performed to determine the extent and rate of root growth, and when you read the figures, you see why. I have run into various accounts of this experiment, and the only thing they don’t reveal is how many lab assistants were blinded for life.

The experimenters studied a single grass plant, winter rye. They let it grow in a greenhouse for four months; then they gingerly spirited away the soil—under microscopes, I imagine—and counted and measured all the roots and root hairs. In four months the plant had set forth 378 miles of roots—that’s about three miles a day—in 14 million distinct roots. This is mighty impressive, but when they get down to the root hairs, I boggle completely. In those same four months the rye plant created 14 billion root hairs, and those little things placed end to end just about wouldn’t quit. In a single cubic inch of soil, the length of the root hairs totaled 6000 miles.

That tonal mix of the casual, the literary, the scientific, an unfussy awe wrapped in smarts — this is what I open my inbox for these days. The difference here is The Atlantic published, cared for, and made available this essay/letter from so long ago. As to the archives of our newsletters? That’s a more complex matter. But as Dillard says: “I merely failed to acknowledge that it is death that is spinning the globe.”

A lot of this newsletter writing is happening, probably, because the archives aren’t great. Tenuousness unlocks the mind, loosens tone. But the archival reality might be just the opposite of that common perception: These newsletters are the most backed up pieces of writing in history, copies in millions of inboxes, on millions of hard drives and servers, far more than any blog post. More robust than an Internet Archive container. LOCKSS to the max. These might be the most durable copies yet of ourselves. They’re everywhere but privately so, hidden, piggybacking on the most accessible, oldest networked publishing platform in the world. QWERTYUIOP indeed.

-

A limit to keep the messages from spiraling out of control for both your sake and mine. One of the problems I’ve had with my other newsletter, Roden is that the letters can become so unwieldy, so wild, so ever expanding, that to even begin one is like preparing to dive down to some sunken ship wedged in a trench. And so by capping things around 500 words means I have an out, and a constraint to keep things focused. And with fifty-two weeks, any spillover from one week feeds into another. ↩︎

-

I worry about the defensibility of their platform though. And suspect MailChimp and the other biggies are getting ready to roll out subscription options sooner than later. That said, although Substack isn’t offering, for example, substantially more beautiful templates than the competition, they do have an increasingly strong, and well-respected brand. I imagine they’ll be an acquisition target sooner than later. ↩︎

-

Although, with “smart” inboxes, and pre-filtered slots, Gmail and other email apps are making it a little less straightforward than before. ↩︎

-

Although, this isn’t necessarily the case in the developing world where email addresses are less common than WhatsApp or Facebook accounts as communication vectors. ↩︎

-

Not to completely disconnect, per se, but to shift it from a plan A, to a solidly secondary plan B status. ↩︎

-

And it has been. So good. So free of spite or cynicism. Perhaps one of the most joyful big-league social networks of the last decade. It certainly felt fresh — light, unencumbered by your previously bloated social graph or too many options — until just recently. Which is why it gained so much traction these past few years. ↩︎

-

I don’t bring any of this up with malice. This is the contract we enter into in using “free” venture backed social networks. They have to achieve scale and maximize profitability, often (paradoxically) at the expense of usability. Frogs boiling in water and all that. ↩︎

-

I understand the design dynamic that is supposedly at play: you’re shown the second image if you’ve already scrolled past the first. The problem is, 99.99% of the time I am certain I haven’t seen the first. So it feels less like an aid to get me to see more content of accounts I love and more an intrusion, an obnoxious nanny state move with little real user benefit. ↩︎

-

That is: Extremely. Or even a Tokyo backstreet late at night. The silence that envolops central corridors of the city can maximally disorient a western city dweller. It’s not an ominous, bad-things-about-about-to-transpire silence, not a silence before some horrible storm, but a true stillness, like standing in the woods with your eyes closed on a windless day. ↩︎

-

About three years ago (or was it four?) I really wanted to do a profile on Casey Neistat. At that time — when he had just begun his daily vlog — he was pulling back the curtain on a really interesting set of life challenges. He was starting a family, starting a business, and being creative with video every single day. It was showing us all the contexts of life, all the messiness. It was an act of heroic focus which would have been unfathomable, had he not been doing it all in public, in real-time. That daily rhythm of his publishing demystified the required effort (a ton). It wasn’t a maybe Casey’s working hard kinda feeling, it was a Holy Moses. This is what going for it looks like. I think his vlog, in the best of moments, became a true archetype of the consistent energy and gumption required to achieve a certain reach and output. Anyway, it was inspired and inspiring and when I think of the power of daily publishing, Casey all those years back, Casey where the first child was still on the way, Casey before having launched his startup, that Casey — the Casey of sleeping fewer hours and running more miles than Fidel Castro — swings to the top of my list. ↩︎

-

And so much better than just publishing on my website. Newsletter subscriptions are the push that RSS promised but never became. And CMD-R to reply is the best, most intuitive commenting system I’ve yet seen. ↩︎