Myanmar’s Farmers and their Smartphones

A dispatch from an Internet revolution in progress

Originally published by: The AtlanticFor six weeks in October and November 2015, just before Myanmar held its landmark elections, I joined a team of design ethnographers in the countryside interviewing forty farmers about smartphones. A design ethnographer is someone who studies how culture and technology interact. A common mistake in building products is to base them on assumptions around how a technology might be adopted. The goal of in-field interviewing in design ethnography is to undermine these assumptions, to be able to design tools and products aligned with actual observed use cases and needs.

Myanmar is especially fertile ground for this kind of work. Until recently the military junta had imposed artificial caps on access to smartphones and SIM cards. Many of the farmers we spoke with had never owned a smartphone before. The villages were often without running water or electricity, but they buzzed with newly minted cell towers and strong 3G signals. For them, everything networked was new.

Almost all of the farmers we spoke with were Facebook users. None had heard of Twitter. How they used Facebook was not dissimilar to how many of us in the West see and think of Twitter: as a source of news, a place where you can follow your interests. The majority, however, didn’t see the social platform as a place to be particularly social or to connect with and stay up to date on comings and goings within their villages.

What follows are a series of diary entries and notes culled from our interviews. The interview teams were composed of three or four people: a translator, a photographer, a notetaker, and sometimes a facilitator.

#Farmer #1

Our first farmer! Thirty-eight years old. Owns fifteen acres of paddy. Has a great head of hair and an 8-year-old daughter. We’re seated atop a raised platform in a makeshift shed in the middle of one of his rice fields. It’s only late morning but the sun outside burns atomic hot. Even the shade is unbearable. Everyone is drenched in sweat. Everything around us is bathed in a golden glow of light reflecting off unharvested paddy.

Okekan is a town northwest of Yangon. The drive takes three to six hours, mostly on the wrong side of pockmarked roads. It’s just big enough for a half-kilometer strip of restaurants and shops, a small market, and a tiny hotel. There are rice fields in every direction. Our first farmer’s village is on the edge of town.

The farmer brought his nephews. They arrive to our shed on 50cc motorbikes. Our arrival is clearly an event. Smiles and hospitality abound. They hand us bottles of water and I feel a relief that maybe our interview request isn’t quite as burdensome as imagined.

Everyone has a smartphone. One Samsung, one from a mysterious company called “Honor,” two Huawei. (We’ll later realize: Honor is owned by Huawei.) Apple simply doesn’t exist in the fields of Myanmar. China dominates. Samsung comes in second to those who can afford to splurge on the brand as a premium. But the more we probe, the less justifiable the Samsung premium becomes. The Chinese phones are cheap but capable. I wonder if this makes Negroponte happy. His one laptop-per-child dream was never fully realized but one smartphone-per-human—far more capable and sensible than a laptop, in many ways—has most certainly arrived. I take notes. We photograph. Get in close, have them pose with their phones. They’re proud. All the phones clock in under the equivalent of one hundred U.S. dollars.

We ask about data. It’s much cheaper now than a year ago, they say. The telcos operate on pre-paid systems. Nobody has a credit card. Everyone buys top-up from top-up shops, scratches off complex serial numbers printed in a small font, types them with special network codes into their phone dialers in a way that feels steampunkish, like they’re divining data. They feel each megabyte. For about 10 U.S. cents you can purchase 25MB of data. If you buy in bulk (although almost nobody does) you can get 2GB of data for 11,900 Myanmar Kyat or about $9.20 USD. Most farmers grab data on their scratch cards in 1,000 or 3,000 or 5,000 Kyat chunks. How long it lasts depends on the user. For some 3,000 Kyats gets them through the month. For others, it lasts only a few days.

We ask about apps. One nephew says he uses Viber to text with friends and family who are outside of the village. But if he can meet in person, he goes to talk in person. He says he uses his smartphone mainly for phone calls, which are still simpler and faster than texting.

The lead farmer mentions Facebook and the others fall in. Facebook! Yes yes! They use Facebook every day. They feel that spending data on Facebook is a worthwhile investment. In fact, check this out, says one nephew. He wants to show us a Facebook post. He’s thrilled. Earlier, he said to us, lelthamar asit—Like any real farmer, I know the land. And so we wonder: What will he show us? A new farming technique? News about the upcoming election? Analysis on its impact on farmers? He shows us: A cow with five legs. He laughs. Amazing, no? Have you ever seen such a thing?

The team I was part of was run by Studio D Radiodurans (or “Studio D” for short), “a research, design, and strategy consultancy,” who have been collaborating for the last two years with Proximity Designs, a Yangon-based social enterprise. Proximity’s impact work is focused primarily on farming and helping farmers. They’ve served over 731,000 rural households as of December 2015—impacting about 3.66 million people.

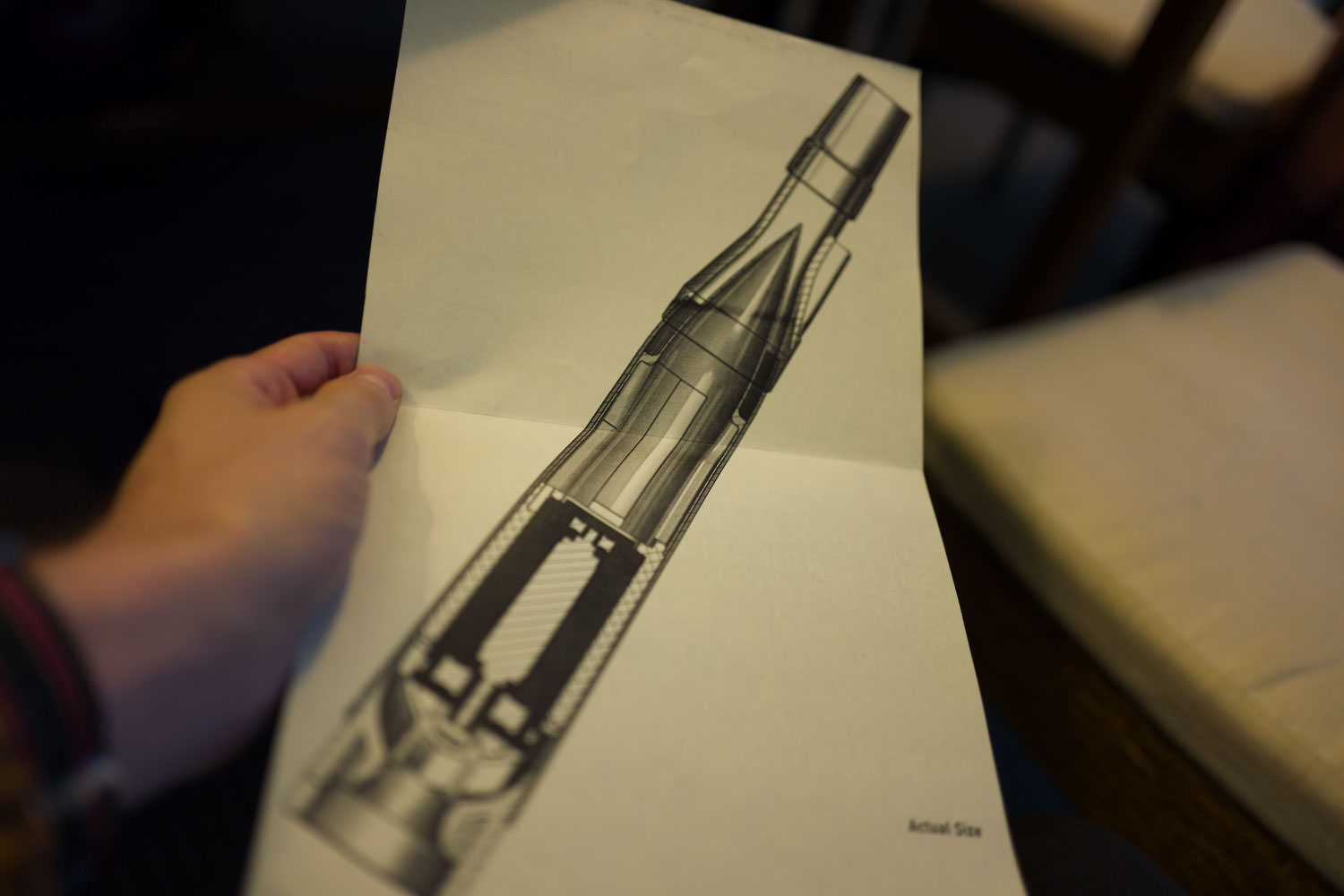

Proximity builds hardware products within an impressive four-story warehouse in the industrial South Dagon section of Yangon. The first floor is showered in sparks from water-pump frame welding and drip-irrigation assembly. The second floor is full of workers assembling treadle pumps. The third floor houses their product-design lab, recently focused on solar-pump design, testing, and production. And the fourth floor performs quality-control checks on water storage sacks that balloon up like carnival attractions.

The foot-treadle part of the treadle pumps are constructed out of readily available and easily replaceable planks and ropes and are worked like a Stairmaster at the gym. Except instead of burning calories, they flood fields with water and create food. And Proximity’s solar pumps — launched just last October after years of research and development as part of a joint project with students at the Stanford d.school — are not only beautifully engineered and designed, they’re among the most affordable in the world. They sell for about $350 and pump roughly fifty liters of water per minute.

Proximity is unique (and lauded) because they approach their impact work with a “design thinking” mindset. Their mantra is to be in the field, get close to the people for whom they are designing, use ethnography to locate “unmet needs,” and iterate through product tests quickly. They have a vast country-wide network of field staff that are often working one-on-one with farmers or villages, helping them implement the products they’ve developed, all the while sending a constant stream of feedback to the home office in Yangon.

That Studio D is so easily able to line up a few dozen interviews reveals the remarkable trust that Proximity has spent years building up. The value of their work is not just in impacting farmers, but connecting them to the world at large.

While Proximity has mastered hardware and rural relationships, the company doesn’t have much experience with software. And so the crux of this Studio D and Proximity collaboration is to remedy that, to assess the current state of Myanmar farmer smartphone fluency and network access, and figure out how to leverage it for maximum impact.

#Farmer #10

Our tenth farmer: thirty-five years old, owner of fourteen acres, educated to the fourth grade. He grows summer paddy and winter paddy. Has three kids. Owns his house—a hut, really—with a dark dirt floor and beautifully textured bamboo thatch walls that let in soft shafts of afternoon light.

We’re not supposed to judge but I can’t help it. He has kind eyes, and an open face, not like Farmer Number Two who felt lost, tormented, didn’t want to be a farmer but was pushed into being a farmer. No, Farmer Number Ten loves farming, loves paddy, loves his family. I feel this. I write in my notebook: I am a horrible, biased researcher.

His 6-year-old daughter beams at us from the corner, her grandmother stands behind with a stern, suspicious look on her face. This is understandable. I’m also suspicious. Of us, not them.

The village still lacks electricity although they’ve pooled funds and a dozen newly planted metal-power poles dot the fields, waiting to be wired up. Through our interpreter I ask, Where do you charge? Farmer Number Ten points to a car battery hanging in the corner onto which familiar USB wires are spliced. He chuckles. I chuckle. Take note.

We ask about apps. The farmer uses Viber and Facebook. He says he chats with a few friends on Facebook but mainly people he doesn’t know. Most of his Facebook friends are strangers. He tells us his brother installed the app for him, and set up his account. He doesn’t know the email address that was used. He gets most of his news from Facebook. The election looms and he loves the political updates. He’s excited but worries about the effect on the price of paddy. He uses Facebook to track rallies. Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy has tremendous presence in these rural areas. We see and hear trucks with jerry-rigged amps and speakers blasting political songs at an almost constant clip.

Farmer Number Ten tells us he used to use radio for news but no more. He says he hasn’t turned the radio on in years. Other news apps—like one called TZ—use too much data. He’s data conscious. He uses Facebook mostly at night when the internet is fastest, and cheapest. Night data clocks in at 5 Kyat/MB, afternoon data 6 Kyat/MB.

The farmer’s phone is several years old. He purchased it used. The screen is scratched and small but everything works. I realize then that smartphone tech crossed the Good Enough threshold years ago. Everything else is icing on the cake.

Myanmar is a country of farmers. Fifty three million citizens, approximately thirty million of whom are farmers. Many of them are now coming online. Rushing online, really. Because of the military junta, mobile SIM cards in Myanmar have historically been prohibitively expensive. In 2014, the cost of a SIM card dropped from about $2,000 USD to $200 USD and then once again, to $1.50 USD. Mobile shops were swarmed.

A Subscriber Identity Module, or SIM card, is a bit of silicon inscribed with a unique and encrypted serial number. From that unique number stems access — to the network, to information, to the ability to coordinate. The military junta wanted to limit access. As the country has opened up, so have its airwaves and access to access itself.

The Myanmar telecommunications industry was wholly government controlled until recently. Now there’s competition, choices. Five years ago you had one choice: Myanmar Post and Telecommunications (MPT). A farmer can now choose from MPT or Telenor or Oredoo. Cell towers sprout wildly — matte-steel contraptions in the middle of rice plots running off their own electricity, their electronic brains housed in small, padlocked refrigerated boxes behind fences that surround the towers. Often the only refrigerators for miles. Micro dots of chill within otherwise vast landscapes of broil.

#Mobile Shop #1

Mobile-shop-owner number one. No acres. Male. Early twenties, extremely skinny. We arrive as a skeleton crew of two as to appear less imposing, less formal. It’s just my hyper-talkative Myanmar colleague and me. In ethnographic design-research parlance this is an ad-hoc interview, i.e., unplanned. We broke off from the rest of the crew and went rogue when we realized we were hungry for context, hungry to talk to the people who sell the phones to the farmers. We learned about this mobile shop from Farmer Number Eight. He said his cousin ran it.

We reach the shop in the town of Kyaukse without helmets on the backs of motorcycles. Kyaukse is formidable, located in the Mandalay region of the country, with a population of around 700,000 and a number of photo studios, mobile-phone shops, dozens of restaurants and guest houses. The city has a bustling and energetic, almost frantic, dusty southeast Asian vibe. Our pop-up, temporary research studio is located in town but the farms we visit all sit miles away. And so we’re constantly on the backs of motorcycles, riding sometimes for an hour or more to get to the fields and houses of those with whom we’ve scheduled interviews.

Back in the town, the shop we’re taken to is miniscule. A single, thin room wedged between some tea shops on a busy side street. Less shop, more shack. Sells mainly used phones. Dozens of replacement screens sit in glass cases like jewelry.

We approach the shop owner. He doesn’t know what we’re talking about. Doesn’t know this so-called Farmer Number Eight. They’re definitely not cousins. Not even acquaintances. But my colleague is disarming in a humble, honest way. He’s not salt-of-the-earth like some of our other crew members (he’s been to college, has never worked a farm) but he’s present and genuine. One of a kind. Obviously harmless. And so the mobile-shop owner acquiesces. Agrees to drink coffee with us for ten minutes. Who are these clowns, I imagine him thinking.

We’re taken across the street, upstairs into a dark room. The windows are blacked out. The few lamps are dim, flickering. Feels hostage-esque. Two coffee-shop employees stand in the shadows in the corner and stare until we order espressos. Then stare some more after another staff delivers them. I take note: Is this how it ends? In a tiny room with bad espresso? And then I’m reminded of a Jan Chipchase—the founder of Studio D—quote: You’re only on track in field work if you feel a bit threatened. Or something like that.

The mobile-shop owner is twenty-five. He holds the only iPhone we’ll see in six weeks. It’s clearly a point of pride. I ask simple questions and my chatty colleague translates them into impossibly long monologues.

“Do you get paid to install apps?” I ask. Five minutes later my colleague finishes translating and the mobile shop owner laughs and says, “No.” Nobody gets paid to install apps.

Facebook is the most popular app, he says. Nine out of ten people who come into the shop want Facebook. Ten months ago SIM prices dropped, data prices dropped, interest in Facebook jumped. I take note. Only half the people who come into the shop already have a Facebook account. The other half don’t know how to make one. I do that for them, he says. I am the account maker.

And what about other apps? He mentions a news app called TZ. Once popular, now less so. He brushes his hand aside and says it’s too data hungry. Everyone is data sensitive he says and reiterates: Facebook. Nobody needs a special app for their interests. Just search for your interest on Facebook. Facebook is the Internet.

Does anyone use Google Play or an app store?

No. No credit cards. No email addresses. Anyway, downloaded installs eat data. Everyone installs apps using Zapya, an app-sharing app. Makes a local network. Everyone nearby connects to it. Allows groups to send data—apps, videos, music—back and forth without using bandwidth. I take note: All apps hand copies of other apps. No official distribution channels in use.

There is a phrase repeated over and over again during my time in Myanmar: From no power to solar, from no banks to digital currencies, from no computers and no internet to capable smartphones with fast 3G connections. It is the mantra of consultants working in these emergent economies. And these emergent economies have one colossal advantage over the entrenched and techno-gluttonous west: There is little incumbency.

There is, however, instability—in government and currency. It’s one of the reasons why a country like Myanmar is just now getting these connections, these devices. The instability significantly increases risk for outside investors and companies. But the residual effect of that instability is a lack of incumbency and traditional infrastructure. And so there is no incumbent electric giant monopolizing rural areas to fight against solar, there is no incumbent bank which will lobby against bitcoin, there are no expectations about how a computer should work, how a digital book should feel. There is only hunger and curiosity. And so there is a wild and distinct freedom to the feeling of working in places like this. It is what intoxicates these consultants. You have seen and lived within a future, and believe—must believe—you can help bring some better version of it to light here. A place like Myanmar is a wireless mulligan. A chance to get things right in a way that we couldn’t or can’t now in our incumbent-laden latticeworks back home.

#Mobile shop #2

Mobile-phone-shop two. A woman. Woman! I take note. Underline. Circle. Finally. Have been talking only with men.

This shop is also an ad-hoc discovery. We were energized, wanted to go deeper after the first interview. Rode that high you get after an unexpected and insightful conversation a bit further into Kyaukse and found this second shop.

My motorcycle driver follows us inside. I realize now this one considers himself the leader. He wants us to do well, but his method of help is intimidation. He stands in the middle of the shop with a cigarette dangling from his mouth and stares at the four female employees. As if this will goad them into opening up to us. He’s wearing Vietnam War era American infantry helmet, high-waist khakis, a leather jacket. His teeth are stained a deep red from all the betel nut he chews. The overall effect is Luciferous. Everyone looks worried. I whisper to my joyful colleague, Uhm, hey man, you gotta tell him to wait outside. Colleague confers and motorcycle man’s face shifts to shame and dejection as he slinks out. Everyone sighs.

This second mobile-shop manager is extremely patient. We give her the creative code name: Patient Phone Shop Woman. In ethnographic-design research everyone gets a code name. She wears a polo shirt with a tiny Yahoo! logo and sits with us on stools in the middle of the shop. There are no customers. We talk for ninety minutes. Does the shop get paid to install apps? Nope, but they rent part of the shop to Samsung. She points to an empty booth along the wall, shrugs, says, Day off.

What are the most popular apps? She does not hesitate in response: Facebook. And then, Viber, Zapya, MP3s, and videos. Ten out of ten people ask for Facebook, she says. Everyone wants Facebook. Farmers know Facebook. All know to ask for it. But, how? How do they know to ask? Because everyone has it, she says. I take note: Who is patient zero?

Are any apps pre-installed?

No. This shop is only a hardware shop. She waves her hand. We look: The shop is LED bright, white, full of glass cases of Chinese phones and an empty Samsung booth. It’s about four times the size of the last shop. Very clinical, very official feeling. Each employee stands at the ready in matching Yahoo! uniforms.

Once a farmer buys a phone we bring them next door, she says. Next door is the software shop.

Our eyes widen. Can we see? Can you take us to this software shop? Of course she can.

We walk across a small road and enter a space opposite the hardware shop. The software shop is like a small, damp cave bathed in flickering fluorescence with a Bladerunner workbench behind three small teller booths. The purpose of the software shop is repairs and installs and reinstalls and consultations. The shop is now empty but sometimes it teems, and there is a waiting bench along one wall, stacks of worn binders atop a coffee table in front of it. The binders are full of song titles, movie titles, each with an ID code. The pages are worn, dirty, torn. Sometimes many wait, Patient Phone Shop Woman says. People choose music and videos while waiting. Zapya’d after. Always Zapya. I take note: Whole economies upon Zapya.

Behind the dirty counter sits a young man. He is the master consultant who performs OS upgrades and installs basic bundles of apps for farmers. Apps to install are chosen by popularity or need or request, he says. We ask if he’s paid to install certain apps and he says no. (We are incredulous, cannot believe there is no app-install shadow economy!) Patient Phone Shop Woman smiles a smile: Told you so.

Master consultant says most customers come in and declare: I don’t know anything about mobile phones. You’re the expert. You install what you think is good.

But Facebook is most popular? Yes. Everyone wants? Everyone. Do people have email addresses? No. He makes the email addresses. Has a stack of pre-made Facebook accounts at the ready. He pre-installs the app and pre-loads friends. Facebook is for news, he says. Popular now but maybe not popular in six months. But for now, he installs it on every phone.

I take note: The masses are fickle everywhere. The notion of a 1:1 mapping of Real Identity to Facebook Identity doesn’t seem to exist.

Does anyone know of Twitter? Maybe two in ten customers. They might ask for it but he doesn’t know what to do on Twitter. Doesn’t know how to use it. It’s not part of my standard app-install bundle, he says. Patient Phone Shop Woman also doesn’t know how to use Twitter, doesn’t see a point.

Viber is used to chat with friends, they say. Good for group chat. New app, Tango is good for video calls with family abroad. Many Myanmar people work in Singapore, they say.

As we’re leaving I connect two and two and realize the shop itself is called Yahoo! Just before we say goodbye, I ask Patient Phone Shop Woman if she knows what Yahoo! is. Oh, yes, she says. Yahoo! is an exclamation of joy. I smile, take note.

The expectations for a Facebook experience are shaped by the cultural expectations brought to the table. No farmer we spoke to had explicit or calcified expectations—they had not joined Facebook ten years ago or five years ago or even two years ago. They had not been indoctrinated into whatever it is Facebook thinks it is. Or what Facebook wants us to think it is. For them, it is a malleable tool. And they have made it into what they want: Largely a news reader. A relatively bandwidth efficient way to read about topics that interest them (the weather, Buddhism, pretty girls in swimsuits).

The Farmers don’t use their real names (“I used my son’s name,” Farmer fourteen told us. Why? “Because it’s a good name!” he said smiling and patting his 1-year-old son on the head.) They don’t have email addresses and so often don’t know their logins. If they get logged out they have someone—often the village Facebook guru—make them a new account. “Friends” on Facebook are friends only because the application calls them friends in the interface. The language of our apps shapes our expectations of our apps, but when the language isn’t your own, isn’t localized, that authority is undermined. “Friends” become something else entirely—random avatars who share an affinity for news stories you happen to stumble across. There is a fluidity to the Myanmar Farmer Facebook experience, one that makes me a little jealous. I feel a bit too locked into the rigidity of our western Facebook expectations. Those Farmers in Myanmar have what feels like a more native fluency than those of us supposedly well versed. Than those of us who say we know what we’re doing.

And yet I can’t help but wonder why Twitter fails to gain traction. It’s simpler. It consumes less bandwidth. It’s model is more minimal, the interface far less complicated. Facebook is a caricature of an interface—the equivalent of the space shuttle, all buttons and dials and switches, so many of which have nothing to do with the core user experience. And yet, these Myanmar farmers wade through the muck, compelled by information hunger.

But Facebook has a compelling advantage over other news apps or even Twitter: The content of many posts and news items live inside Facebook itself. There are external links, but most of the article summaries and photos are self contained. As Facebook continues to ramp up their Instant Articles—special versions of web articles that are leaner, load more quickly, and are Facebook optimized—the amount of content that lives in Facebook will only increase. For those who are data sensitive, this is a clear virtue. One certainly worth whatever learning curve may come with the platform.

Twitter recently announced that it will allow up to 10,000 characters “below” the tweet. If critical news can live inside of Twitter, in a fundamentally less bandwidth intensive and a simpler model than even Facebook, then the popular interest may shift. There is no explicit brand loyalty amongst these farmers.

#Pop-up Ethnographic Design Research Studio, Okekan, day 36

Two Myanmar men are dancing in the grass, bringing down long pieces of bamboo hard against the ground. They hop, lithe, graceful in the tall grass next to the pond. I take a break from note transcription and photo editing, stand, watch the men. I ask Lauren Serota, the leader of our ethnographic-design research team, what they are doing. She doesn’t know. They are precise and nimble, nearly naked. We stare. I look at my smartphone weather report. The 3G connection in our rural pop-up studio is strong. Stronger than in the city. Almost double the speed of Yangon. The Real Feel™ is a billion degrees in the sun today. The phone just says: Give up.

We’re sweat soaked in the shade. The electricity has cut out again. A man whose name I consistently mishear as Muhammad is supposed to come and start some mysterious generator for us. The fans are dead. Everywhere there are bugs. So many bugs upon everything, everyone. Multiplying as twilight falls. And yet the men in the grass dance! In the sun! They stop. One reaches down, gingerly, and lifts a fifteen-foot water snake by the head. It’s still alive, writhing. They take it around the corner, behind a wall, and fry it into a curry. I return to my notes. Farmer Number Fifteen loves the famous Myanmar weatherman U Tun Lwin, now follows him on Facebook. I hunt U Tun Lwin down, follow him too, in solidarity, although I’m pretty sure I know what tomorrow’s weather will be.