Walking Alec Soth

What it felt like to walk through the artist's solo show in Japan

Ridgeline Transmission 145

The other day I walked through American photographer Alec Soth’s oeuvre.

Somewhat randomly (Instagram?), it came to my attention that he had a new solo exhibition a) in Japan (!), and b) down the road from me (!!), and c) that he was going to give a talk (?!). So, I set a timer, called the museum at the appointed hour, and snagged a ticket to the talk over the phone, as is the technical wont of contemporary Japan. (“Your reservation number is 20.”)

Before the talk I walked the show. I walked it three times. The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama is a seaside building down the road from the hip village of Hayama (a kind of Hudson Valley × Venice Beach of Tokyo), next to the Emperor’s summer home (a little at odds with the vibe; as one old local put it: We don’t like the emperor much and wish he didn’t have a home here (!!)). Opened in 1951 as the first public museum of modern art in Japan, it is one of these slightly odd middle-of-nowhere museums that Japan tends to have a lot of.

Anyway, Soth has taken over the place — his first solo show in Japan. Arranged into, effectively, six spaces covering five “periods” (or books) of his work. Plus a showing of the documentary about him and his work, Somewhere to Disappear (2010). The space was arranged in such a way as to encourage looping, since the entrance was also the exit.

I find I have about an hour of “focus” to give to any museum. Friends who can spend hours upon hours cavorting in museums baffle me. Maybe I look too hard. But after an hour I find my eyes glaze and connections between the art and the brain grow tenuous and I’m not really “looking” anymore. So I tend to be militant and have strategies for walking museums.

First, I try to just rush through it all: What’s here? What do I want to “gift” my fragile, social-media destroyed attention to? How big is this place? What catches my eye?

Then I go back and do a slow sweep over the pieces that grabbed me. If a certain area is busy / backed up with folks (as most entrance areas tend to be), I’ll skip it whole hog. There is always enough to look at, too much to look at, to really look at.

I’ve been looking at Soth’s work for years, mostly (sadly), online, but also in books. I’ve made it a point to invest in building out my photo book library and his books (mostly from MACK) makes for easy purchases. Though, no matter how beautifully a book may be printed, there’s something special about the context of a museum, the largeness of a print, that elevates the image in question to yet another (not necessarily better! books and their deliberate sequencing are powerful in their own special way) place. His stuff was huge in Hayama. Just massive. It made me remember what big prints could do and how they felt up close and how they felt to pass by — to stroll beside in a kind of casual glancing way. Looping around, coming back, jumping forward, engaging via non-linear wonky routes.

Because Soth shoots with an 8x10 camera, the prints are lush with details. Almost overwhelmingly so — they sometimes feel like they’re going to devour the print, like the billion branches as seen in a forest shot will eat the print itself given a few seasons. There’s something fun and spellbinding and disturbing about standing before so much texture and life. Certainly, it’s easier to “notice” quirks about the shots when they’re this big, when the plane of focus is so obvious, in ways that are easy to miss in the size of a book (like a disco ball in the forest is out of focus which, given the speed at which Soth shoots, the deliberateness of his setup, can only be intentional).

But to focus on the details or the technical quality misses, I think, the point. I’ve never cared much for the technical aspects of photography — what camera is being used or how sharp a lens is or how the print in question was made. (My camera reviews include technical details, sure, but the overriding impulse for those review is: This tool! The specialness of this tool unlocks X and Y and Z — go forth with this tool, forget about the tool, and make!)

The true power of a museum exhibition is the power of the walk, the stroll. So I focused on just that. A few thousand steps, around and around. Stopping, stepping back, getting close, nearly pushing my nose against the glass. Each room had a bench and I sat on those benches and looked, just looked at how other people were looking. Folks in pairs and alone, pointing, bending, dipping, eyes often growing wide. Which images caught their attention? Which were tough or “embarrassing” for folks to look at? (A nude couple sitting in the corner on a carpet rarely got more than a cursory glance whereas Soth’s “classic” tourist shot of Niagara Falls made huge often commanded minutes of gaze.)

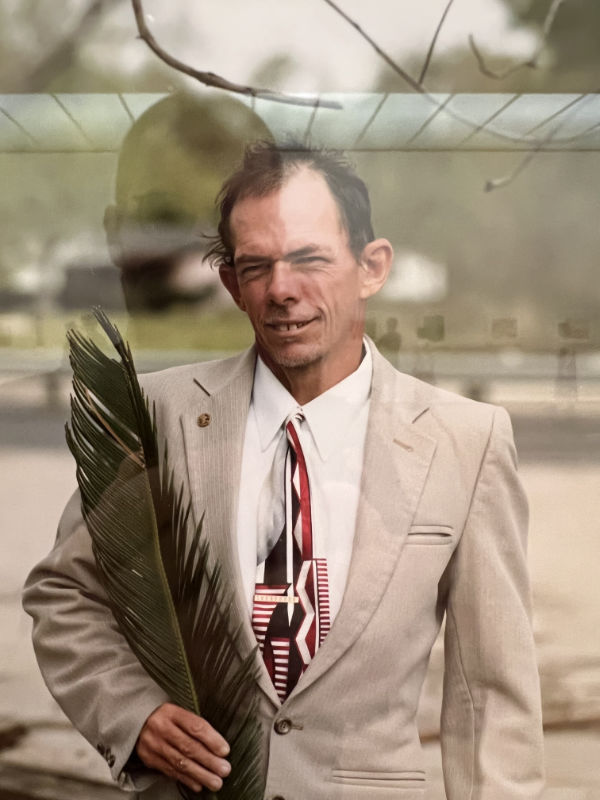

In his exhibition talk, Soth said that the point of the prints isn’t the details, which was nice to hear. And that his use of an 8x10 (The very first question of the Q&A being: Why do you shoot 8x10?) had little to do with the technical aspects of it, but rather the ceremony of the tool. He spoke about approaching people on the street without the camera, explaining his project, getting permission, going to his car and then, finally, bringing the camera over. The largeness of the object and ceremony of the process making those chosen feel special, attended to in a way many of these people in frame had never been attended to before. He was describing grace: the presentation of and delivery of grace (he mails everyone he shoots a print (“I almost never hear back from anyone!”)). Soth went on to say that the reason he likes his camera is that it produces this social effect, and that the images it makes are ones of captured space — capturing the volume of space between him and the subject, between the chemical-slathered negative and the couple sitting on a bench, on the floor in an apartment, on a moss covered stone, carrying a feather in a suit, shirtless touching a daisy.

It was also nice to meet Soth himself. He was as gracious as his work would have you believe him to be. We had emailed a few times, and last year I woke to the surprise of Kissa by Kissa being featured in one of his excellent YouTube videos. “So that’s what you look like in real life,” he said as we shook hands. We only got to chat for a few minutes before folks started to ask for selfies. Once the selfie dam broke, a conga line formed and I went back to walk the show once again. It was almost closing time (a great time to visit a museum) and the crowd inside had thinned. I walked slowly, now largely alone, thinking about the whole of the show, the “collection,” and how images placed across and next to each other create a new space, occupy a new volume, one that you enter into and break apart with your body. I didn’t stop to look at any particular image, that didn’t seem to be the point anymore. Eventually a sad melody played over the museum sound system — quietly, almost imperceptibly, directionless, as if the song was radiating from the photographs themselves. Ever more grace: A gentle way to signal that the walk was done, it was time to go home.