Walking the Cotswolds,

Walking Japan

Notes on a week of walking through rural England, comparing it to rural Japan

Ridgeline Transmission 143

The Cotswolds are like Disneyland, they said. And I suppose that was meant to be pejorative. But as a kid I grew up going to Disney World, over and over, staying in stumpy two story motels, playing Street Fighter II, and having the time of my life. So Disney and its Lands and Worlds sit well in my mind. And anyway, the Cotswolds is only like Disneyland if Disney extended forever, to the horizon, and then the next horizon still. If Disney’s land was utterly boundless in all directions and was crisscrossed by thousands of years of walking routes, filled with docile sheep and cattle and majestic horses aching for a carrot or two. A landscape of abundant fecundity. It felt fantastical and fastidious in its manicure; the hedges and stone walls and well-marked fields — everything — was pixel perfect. It became a kind of game to find a flaw, some brick or stone that might be out of place or neglected. There were hardly any. And in that sense we — as a group of ten walkers — were struck on day three or four: the landscape we strolled past was “done,” “complete,” “finished” and had been done for some time. It was a whole thing, without lack of any piece.

In this way it was a joyful walk — like meandering a working museum. It didn’t feel phony or lame or forced, but it was unnerving, in the way that any static system is unnerving, unnatural. Hold your hand out before your eyes, hold it still, no stiller. You can’t. It shakes. No matter how hard you try your system is chugging along, the brain calculating a billion moves each second, and from that fundamental life of the system comes subtle variance. The Cotswolds lacked the variance you’d expect in a living system. And yet!

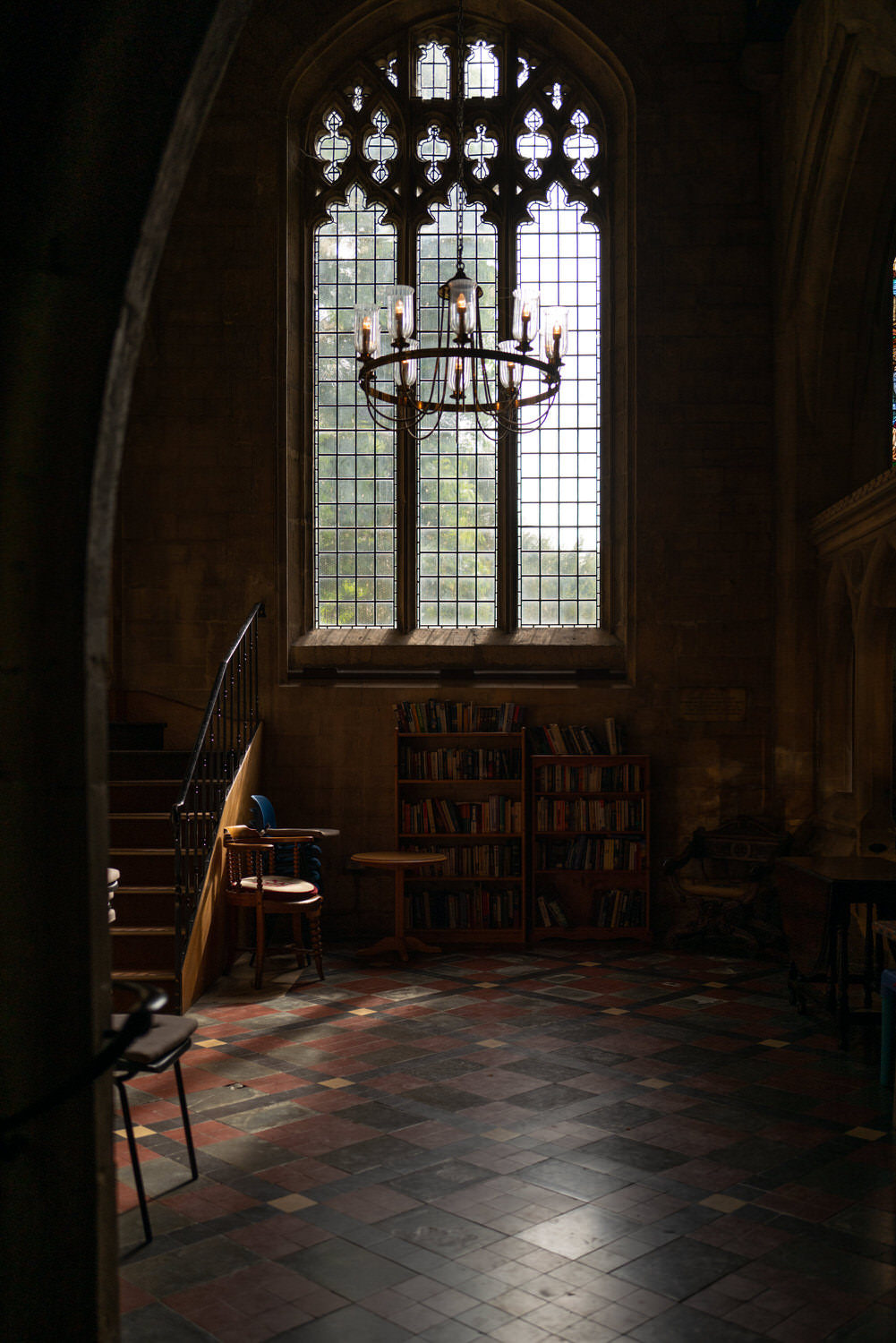

It was astounding. The completeness was all pervasive and seemed to drill itself into the minds of us walkers: Done. Done. Done. And though it was done it was also somehow alive — the people were kind and caring and compassionate. Everyone eager to chat. The flora in full bloom — wisteria draped over 17th century walls like bluish-lilac lace. No accidentally derelict leftovers, nothing was shuttered. When I scampered off the true touristy old routes — the hyper-manicured bits — the care seemed to continue on to the edge of town. I found a laundromat, which ended up being not a laundromat. The staff kindly routed me to the proper one. Just a five mins walk dear, they said; it took 40 minutes. I got the impression no one had ever walked these streets before, no one had gone more than a few meters without a car. But I got to wander the most incredible suburban sameness; a new sameness wrought from that same old Cotswolds’ stone, melding into the old oldness, patina to come.

Laundry was then done by women quick to laugh, who shrank my shirts only slightly. The laundromat itself, cheap prefab nothingness cradled within a larger bassinet of timeless stone.

If the Cotswolds is done, complete, finished, static, then in comparison Japan feels endlessly dynamic, like an ice sculpture shot through by bazooka. This may seem counterintuitive, but a host of qualities — the aging population, the changing face of countryside towns and villages, the shuttering of long-run shops, the scars of the (relatively) recent wars — all lend Japan a feeling of recent and continuous churn. You walk and realize that this is not how these towns looked thirty years ago, never mind a hundred years ago or a thousand. Sure, you have deliberately preserved or rebuilt towns like Magome or Tsumago on the Nakasendō. But go just beyond those tightly constrained villages and you’re back in a countryside whisk of crumble and depopulation.

In the Cotswolds, it felt like the walk we did was a walk we could have done in 1683: same hedges and walls, same shops, same dead people, same high streets, same pubs, same horrible beds. Because the beds — my lord, were I to complain about only one Costwolds thing it would be the beds (well, and the Covid). Soft, those Cotswolds beds, like sleeping in a hammock made of blue cheese. Now, I must admit: I am a fully converted thin-futon-atop-tatami kinda guy, a lay-down-and-have-gravity-splay-a-body’s-spine-out-upon-an-unyielding-mattress kinda guy. I don’t like to struggle to get out of my bed but the Cotswolds folk seem to adore it. My limited empirical data indicate that they desire to sink into a squishy thing that envelops the limbs, that places pressure on random points along the torso, to have no airflow around the skull. The data evidence desires to inhale the face-goo of a million other oily noses rubbed about the pillow, and to then, come morning, to roll themselves out of the contraption like a sausage escaping a hotdog bun. Anyway, I did not like the beds.

The beds in Japan — you get the rare dud, but I find them mostly excellent.

Japan on a whole — continuously changing in remarkable ways. Even the “old” stuff, the landmarks like Ise Shrine are under constant renewal, max out at twenty years. Sure you can find “true” old stuff — a stone marker here or there, a fat tree that wasn’t chopped and replanted for post-war cedar harvesting — but it isn’t like the Cotswolds; the old can feel accidental in Japan. In the Cotswolds it feels elemental.

I kept bouncing between these two mindsets — one of the continuous and well-established surface churn of Japan and one of the seemingly static view the Cotswolds provided. In this way the Cotswolds is novel and in many ways “easier” than Japan. England appears made for walkers, for walking. You feel this quickly on the old roads. I downloaded a Gaia GPS overlay called Open Hiking Map which lays out all the old “Ways” — the Cotswolds Way and Winchcombe Way and Gloucestershire Way and Windrush Way and on and on and on, Ways forever, Ways until the end of time. Infinite crisscrossings, you’re never more than a few hundred meters from yet another countryside route, away from roads, cars, paths chopping up farms and pastures. You’re never far from the suspicious gaze of sheep, their odd bleats, the murderous shrill of lady foxes. It’s right there, a tumble of walks, a waterfall of walks readily available to any able-bodied walker.

These routes and their limitless permutations makes tying together a traffic-free English walk effortless; a more difficult task in Japan where so many of the old routes have been coopted by roads and highways. This speaks to a fundamental topographic difference between the two countries. In England, the old routes are multitudinous because there are no obstacles: no mountains, no crumpled earth to stop a route. There is no “easy” path because they’re all easy. Whereas in Japan, the old routes are few and far between, and, compared to England, seem to vibrate between “tough for most” and “ascetic mountain training.”

The English roads can be sauntered by all. The most “intense” stretch being a gentle incline over the course of an hour or two. It is, truly, rolling hills all the way across the land (for hundreds of kilometers in the Cotswolds at least).

This made it ideal for walking and talking, which was the purpose of the trip. Ten folks, walking across the English landscape, talking about a different topic each day. There was the “moments where you experienced profound personal growth” day, “aliens?” day, “authenticity” day. There was the day we jabbered about film and media and the day we talked “future of democracy” (yikes!). And we spent a day sharing “what we learned from the pandemic.” Kevin Kelly and I have run walk-n-talks before; the structure is pretty dialed in. A topic is chosen before bed. We chat the next day as we walk, and then we gather for a Jeffersonian-style dinner in the evening. One person talks, then another. Everyone listens. It works surprisingly well.

As for these dinners, you’d think it would be hard to accommodate a group of ten on short notice, but almost every night we had a great, quiet space to hold our hushed discussions. Mostly we ate outdoors or in private rooms at the back of pubs (one night we commandeered the snooker nook). If the music is loud, they’ll often turn it down or off for you. Never hurts to ask. Who knows what we looked like to the wait staff — maybe Quakers, or evangelical Christians engaging in missionary strategy roundtables.

In the Cotswolds, big luggage was forwarded from inn to inn. You can do something similar in Japan. Either on “official” tours (they’ll handle luggage), or — as I often do — use Yamato to ship stuff a day or two ahead. It’s reliable. All Japanese hotels have forms and arrange pickup. And you can stick an airtag in with your protein bars for extra tracking.

Infrastructure — the inns with luggage forwarding and plentiful pubs with ample dining space — is critical to the success of a walk-n-talk. It’s why we chose the Cotswolds — the walks are easy and replete with infrastructure. Japan has conbinis everywhere, but the Cotswolds for the most part had serviceable supermarkets in each village.

Ages of walkers in the group were spread between thirty and seventy. Distances were reasonable. If you’re organizing your own multi-day walk, aim for shorter — worst case on a short day is hanging out by a river in the destination village. Long days strung together can wear a group out fast. In some ways, where you’re walking almost makes no difference. This isn’t strictly true, of course, but it is partially true. You become so engrossed in conversation throughout the day that huge swaths of land pass by without any conscious acknowledgement.

Each night in the Cotswolds, right around twilight — which seemed to arrive at eight or nine p.m. — the sky would be cast a golden pale and the air would fill with excited birdsong. It was my favorite part of the day. Tweets galore, mellifluous and wild. Often right at the end of our dinner (we ate early), almost as a signal that it was time to pack it up, get going folks. And so I would take the invitation: Pack it up and wander the old roads of the tiny village, camera in hand. A conference of birds taking place overhead, cats roaming below, dogs being walked, and the last of the early summer light keeping the lesser stars at bay.

Yep, it was pretty good, the Cotswolds. Even the food. I’d say walk it if you get the chance. Or string together an English improv walk, a walk with no plan, just jumping from Way to Way as you encounter new ones, tent on your back, camping and enjoying the rolling openness of it all.

They said it’s like Disneyland, but it felt like a place much older and grander to me.