Hellooo Walkers — I survived the recent “heatwave” in Sydney mainly by staying inside and working on, planning, and mapping out walks (it hit 49.5℃ in parts of the country). Popped out for two events: 1) A concert at the Rose Seidler home, a place so beautiful and rational (and relatively cheap to build!) that you can’t help but wonder why all houses aren’t made like this, and 2) A cycling architecture tour of the city, on Lime electric bicycles. Fascinating to see how Lime has whittled these things down — no gears, no pedal assist adjustments. Just raise the seat and go. Not bad in a pinch.

But back to walking:

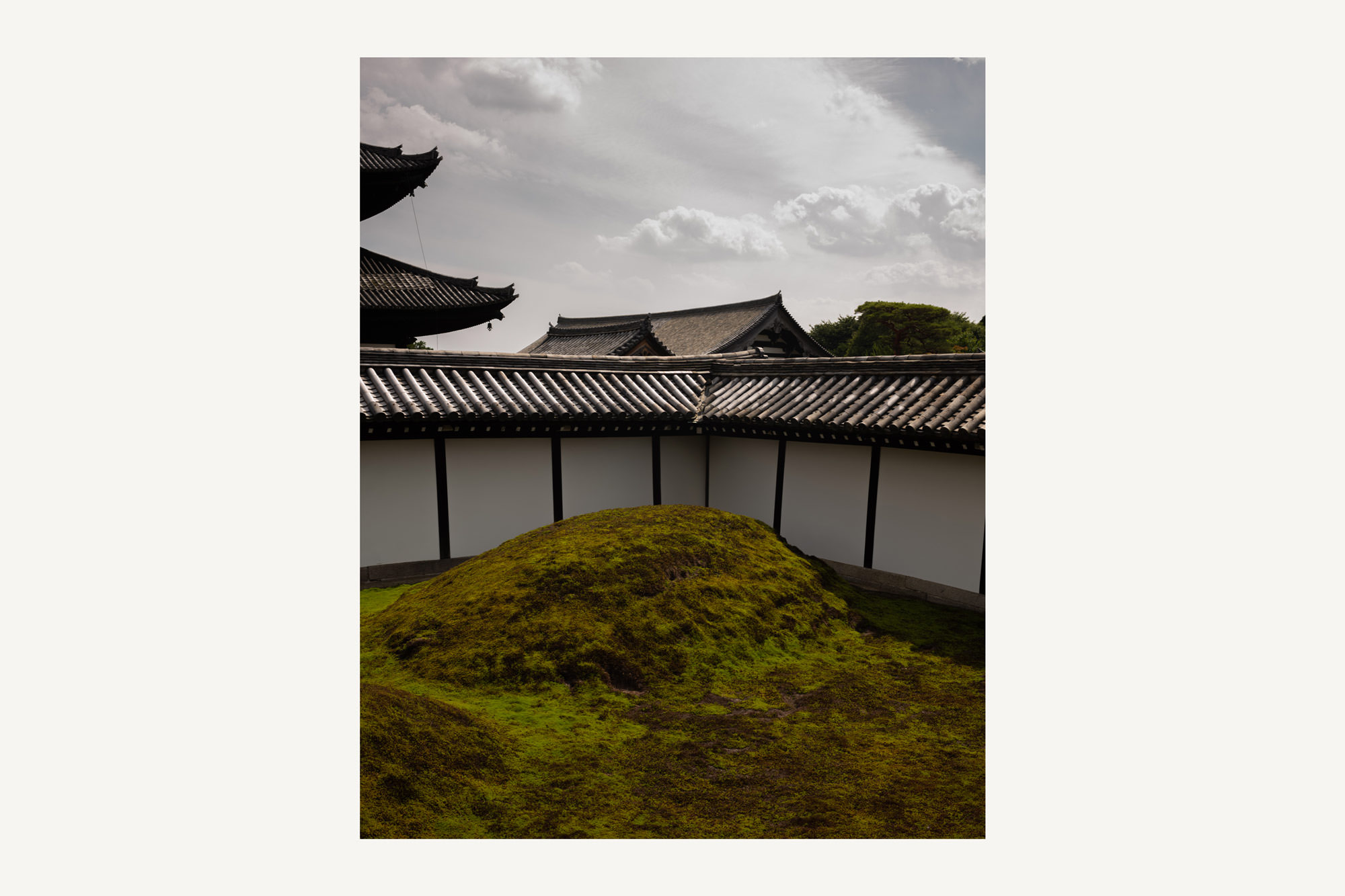

Where are the big walks of Japan? Three stand out as long (more than 500km), historically relevant, and somewhat linear: Tokaido, Nakasendo, and Shikoku’s 88-Temples. (Kumano is historic and has more than 500km of paths but, as we discussed last week, it’s not all explicitly contiguous.)

The Tokaido and Nakasendo connect Tokyo (“Edo,” when first made) and Kyoto, and are the main ways of the Gokaido — five routes — established in the early 17th century. The Tokaido traces a costal route between the two cities, and the Nakasendo a more mountainous, northern route. All the Gokaido terminate or start from Nihonbashi, just down the road from the Apple Store in Ginza.

Nihonbashi, a bridge to which you can easily go and see and lay your hand on its stone railings, the home of the so-called “zero milestone” from which so many measurements of distance in Japan have been made — arguably one of the most important points of convergence in the country — is, today, covered by an expressway. A bridge atop a bridge.

Arriving at Nihonbashi is a bit heartbreaking. What should be a stunning little bridge over one of the once active and numerous Tokyo waterways, is instead squashed, reduced to a reminder of the heavy-handedness of post-war rebuilding. And of how the Olympics can induce a kind of irrational reconfiguration of host city.

English artist Richard Long has walked, reconfigured, and obsessed over lines for the past fifty years, with some of his walks taking place in Japan. The Tate describes his image, “A Line in Japan,” from their collection:

This colour photograph shows a view of a dark rocky ridge on top of a high mountain that peaks above a layer of clouds. On the ground can be seen a straight line of carefully laid out stones that recedes along the ridge at a perpendicular angle to the picture frame. Below the photograph on the off-white paper mount are five Japanese characters, which are translated on the two lines below: ‘A LINE IN JAPAN’, handwritten in red pencil, and below this ‘MOUNT FUJI, 1979’, handwritten in graphite pencil.

If you’ve been to the art island, Naoshima, you may have seen some of Long’s pieces at the Benesse House Musem. The BBC has a somewhat hilarious televised discussion of Long’s work from 1983 where two curators argue over what is or isn’t art. One digs in his heels and invokes “magic” to describe the effect of the lines Long makes with stones in country landscapes or the circles he paints with mud on gallery walls.

I’ve adopted a similarly non-stance stance — magic — when thinking about the lines of Tokyo as I’ve walked the city these past eighteen years. Just assume everything is an aberration, transient, because Tokyo is nothing if not a city devoid of nostalgia for itself. Buildings go up and down with seemingly no rhyme or reason. There’s a shack on a corner in Akasaka next to the TBS mega-structure that hung on (continues to hang on?) for decades. Similarly, a perfectly fine ten story office block in front of Gaienmae Station might suddenly come down over the weekend. You simply have to assume that anything you love or that has sentimental value will be gone the next time you pass it by.

Magic, constant reconfiguration, endless remaking — understanding these is the only way to keep perspective on historical points like the zero milestone as trucks trundle above and you’re below in the shadows like Gollum. Expressway or not, the lines drawn out from Nihonbashi don’t change, even if the shops along the roads most certainly have. Five steps out from the bridge under a bridge and you’re back in sunlight, the Tokaido and Nakasendo leading into the countryside still beginning from that same, historic, place, the world reconfiguring itself around them.

Fellow walkers

“Early morning sunday walks with my dad, over the limestone slopes and boggy groughs of North Yorkshire. “

“I wandered from the far South to the far North, from the Andes and the desert to the forests and the sea. Born into a family of immigrants, some by force some by choice, not all too surprisingly ended up a wanderer myself.”

“Despite being born and raised on an island so flat that the highest point was the levee bank protecting us from flood waters, it’s now the mountains that speak to me. The taller the better.”

“Growing up in one of the most isolated cities in the world wasn’t isolating enough so now I live halfway across the world in a cottage in a glen.”

“I share your vulgarity in speech, though mine was birthed from a sort of privilege, an all boys Irish Catholic boarding school, aged 12-18."