Ridgeline

A weekly newsletter by Craig Mod on walking, Japan, literature, and photography.

About the letter

Over these last few years I’ve walked thousands of kilometers of Japanese pilgrimage paths, old roads, and historic mountain trails.

I’ve taken tens of thousands of photos.

I’ve led walks with incredible folks — talented folks, kind hearted folks — from around the world.

And slowly, through the process of walking and observing, I've developed a sense of what makes a walk work. What makes a walk great, and how walks that seem great can be made better still.

This newsletter is a distillation of these observations and collected notes, paired with a photo, and shared with you, weekly. We'll be joined by Sebald and MacFarlane and McPhee, Basho and Gellhorn, Lee and Chatwin and Shepherd and anyone else who has committed themselves to a walk.

It’ll be a little literary, a little wacky, a little scattered. But it’ll all be bound by walking — a shared love for movement, as we search for some platonic walk, an impossible walk, together.

Ridgeline?

But why ridgeline? Oh, man, because that’s where some of my biggest smiles (strange smiles, sad smiles, punch-drunk dumb smiles) of the past years have been found. Because ridgelines are gifts. Especially after a seemingly endless climb or descent. If a peak is a crescendo, then a good ridgeline is the place where a mountain resolves itself. Shed of some high-note, ridgelines are where you begin to feel the creaky subvocalizations of old tectonics.

Ridgelines are liminal, in Japan they can seperate prefectures, one parcel of land from another. Ridgelines are connective tissue. They are the vertebrae of dirt and rock that feel, to me, most like life itself — straddling precipitous fissures where your attention must be focused on every step.

And yet! The best ridgelines induce an impossible lightness. While I love to savor a good ridgeline, to walk slowly with care, looking out at the afforded views all contemplative and thinky-like, I find myself sometimes rushing — running, idiotically — along their gentle undulations, lunatic laughs rising seemingly out of nowhere, a few millimeters from slipping to a maimed doom. Which is to say: A good ridgeline inspires you to embrace a childlike nuttiness.

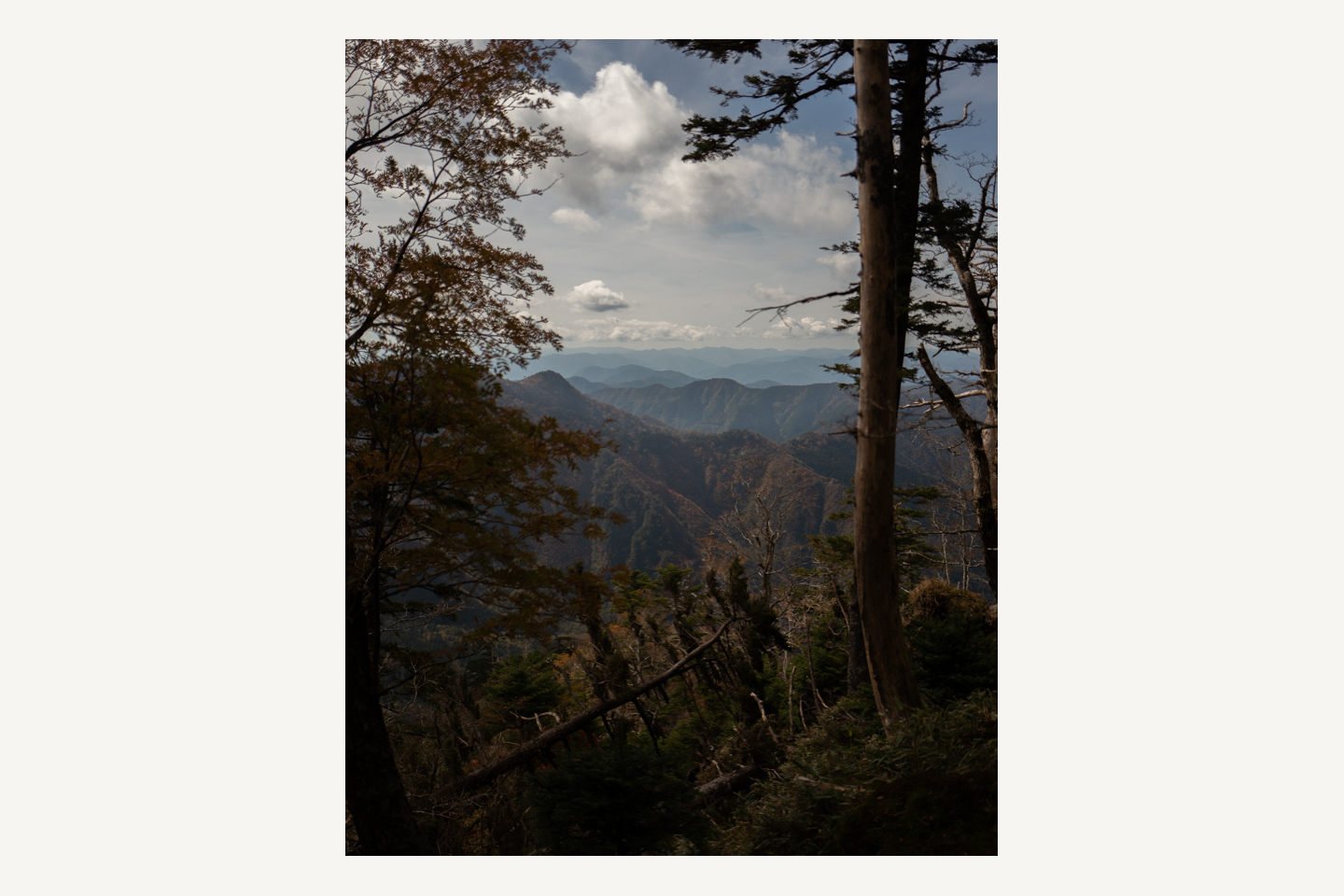

Ridgelines become maps, veins of the mountains. They form the base physiognomy that make ranges so eminently photographable. They reframe past walks. Walking along one, in the distance you may see other ridgelines — perhaps ones you’ve walked before but have never seen from afar.

Maybe, best of all, they are delightfully subversive. Ridgelines rob summits of a bit of their majesty. For, those of us who often walk know rigelines are the blue-collar, working parts of the mountain, the bits beaten down by thousands of years of human stomping in service to gettin' places, and many more millennia in aid of boars and deers and monkeys and bears.

And so the best ridgelines are not only in conversation with the past, they are embedded with that conversation — like paleolithic braille.

For me, a good ridgeline is where it's at. I don't explicitly aim for them, but am grateful for their arrival.

After all that blathering, how about it? Shall we take a little walk out there?