Studio Goodbye, Studio Hello

Closing up my old studio of eight years, moving to a new one

Ridgeline Transmission 211

Ridgeline subscribers —

Some six and a half years ago I wrote the first Ridgeline sitting on the second floor of my Kamakura studio. I had been living there for two years by then, and the place had already subtly and not so subtly changed my life in so many ways, that I get a bit woozy just thinking about it.

I moved down here (a quick, single, forty-five-minute train ride south) eight and a half years ago not because I had gotten a sick of Tokyo, or felt a compressed by it, but simply that I felt a shakeup was in order. I was spending more and more of my time on big walks out in the countryside (still working up the courage to write about them). I was independent. Didn’t commute anywhere. Moving down by the ocean and mountains seemed like a sane choice that carried almost no risk, almost all upside. I had been hiking the old paths of Kamakura for years by this point. So I poked a friend who lived down here, and they had a friend who had a friend, and a house appeared. The rent was hilariously low (even now, a number I am in awe of: less than a thousand bucks a month; this has always been Japan’s sleeved ace, affordability, and one of the big reasons I’ve been able to do what I’ve done these past twenty-five years). When I first saw it, I passed. Too big! What could I do with all that space?

But the idea of it lingered. Day by day I began to imagine just that: What I could do with all that space. Not that it was that big. Two stories, with about 90 m2 of usable space. A living / dining room / kitchen, a six-mat tatami room, and a bedroom. That’s about it. But, boy oh boy, that was a lot for this guy. Until this place, I had never lived in an apartment larger than 30 m2. My total ownership of furniture was: A low table I made myself out of timber cut to spec at Tokyu Hands (I worked sitting on the floor until I was thirty-five), and two bookshelves. Oh, and a small folding chabudai table I’d bring out to have dinner with guests.

So, I took it, the house.

I arrived at the new home in the early evening. All my stuff was on the floor in the living room (it all fit easily in one room). I sat in the middle of it all and burst into tears. That was not the reaction I expected. But I was so filled with a sense of … bigness!, of space! of having emerged from some … I dunno, self-imposed scarcity prison, that I got up and ran up and down the stairs, through the rooms like a happy golden retriever. So much space! And it was mine.

I spent the next three months building out the place, getting furniture made from craftspeople in Hiroshima and Gifu, folks whose work I had always admired but never had the space or money for. I was investing in myself after a lifelong drought. Buying bookshelves. Mounting a projector on the ceiling. Ordering a “real” desk. A “real” work chair (some used Steelcase off Yahoo! Auctions on which I’m sitting as I type this).

My heart expanded. I fell in love because of this place. Or this space made me realize it was time once again to fall in love. This space seemed to open up the best parts of my heart, parts that had been shutdown for a long while. That, too, was unexpected. But immediately my impulse was to share.

I hired a gardener. The garden hadn’t been touched in ten years. (The house, amazingly, hadn’t been occupied for about three.) We redesigned it, planted new trees. Today those trees are formidable creatures.

Ridgeline started upstairs, as did SPECIAL PROJECTS. I broadcasted dozens of livestreams up there. (Which SP members have access to on the members’ site.) I launched my On Margins podcast from the tatami room. Several of my biggest walks began by stepping out the very front door of this place. I started walking the Nakasendō in 2019 — the walk that would turn into Kissa by Kissa — here, walking from my house to Yokohama on day one, wondering just what the hell I had gotten myself into. I walked the Tōkaidō the first time, leaving from here, walking north to Totsuka, and then cutting back to follow the route during the height of the pandemic.

My first “real” books (books done on my own, not co-authored, not hedged) began and took shape here. Kissa was my first pandemic project. When the world ground to a halt, and I was “stuck” here, I dove back into book design and livestreams. Let’s make something beautiful and special; hell, we got the time. I built Craigstarter on Shopify, and launched Kissa in August 2020 upstairs, on a livestream with members with my bed in the background. The explosive sales and interest around that project changed (truly) the trajectory of my life / career / business.

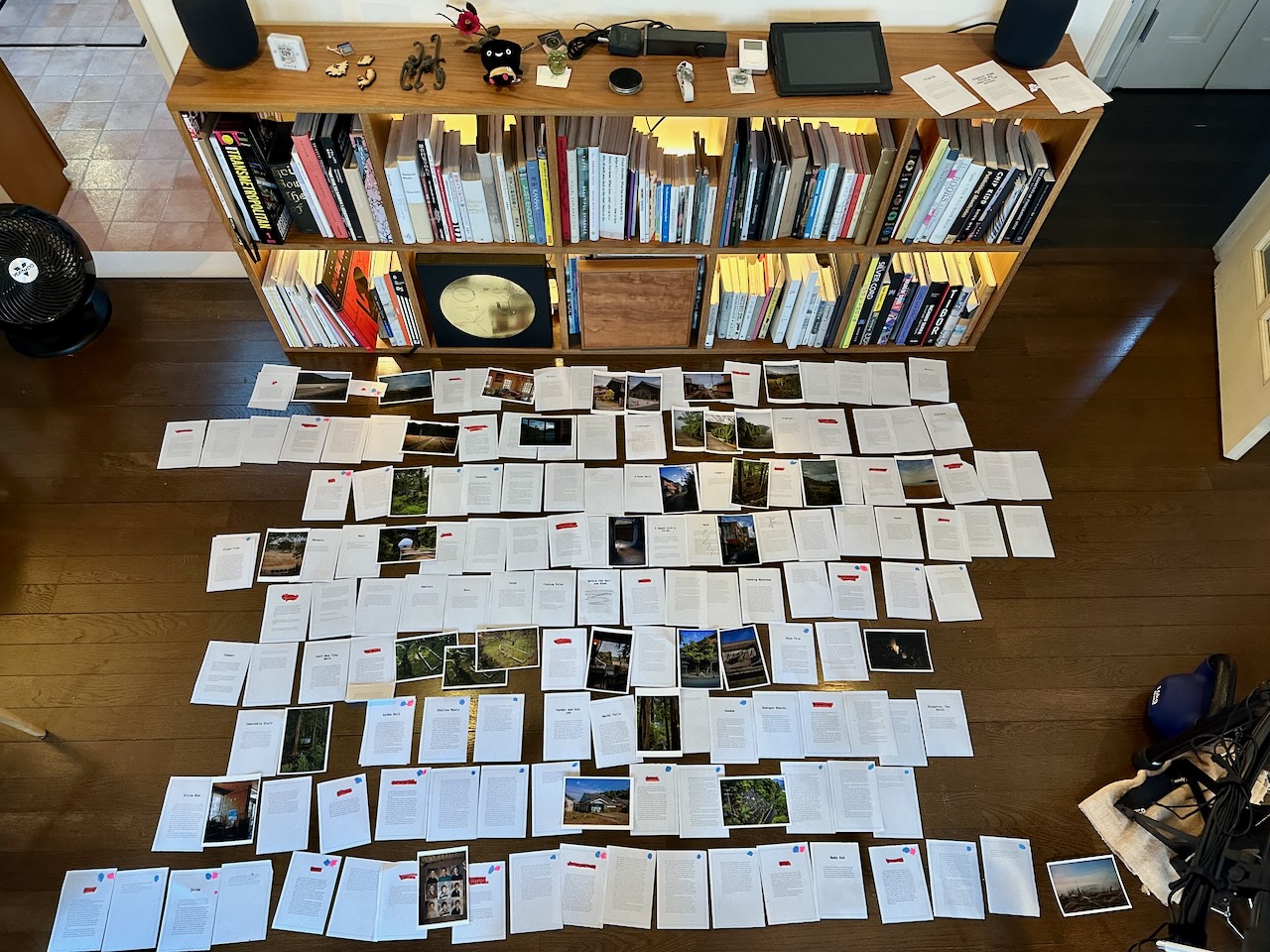

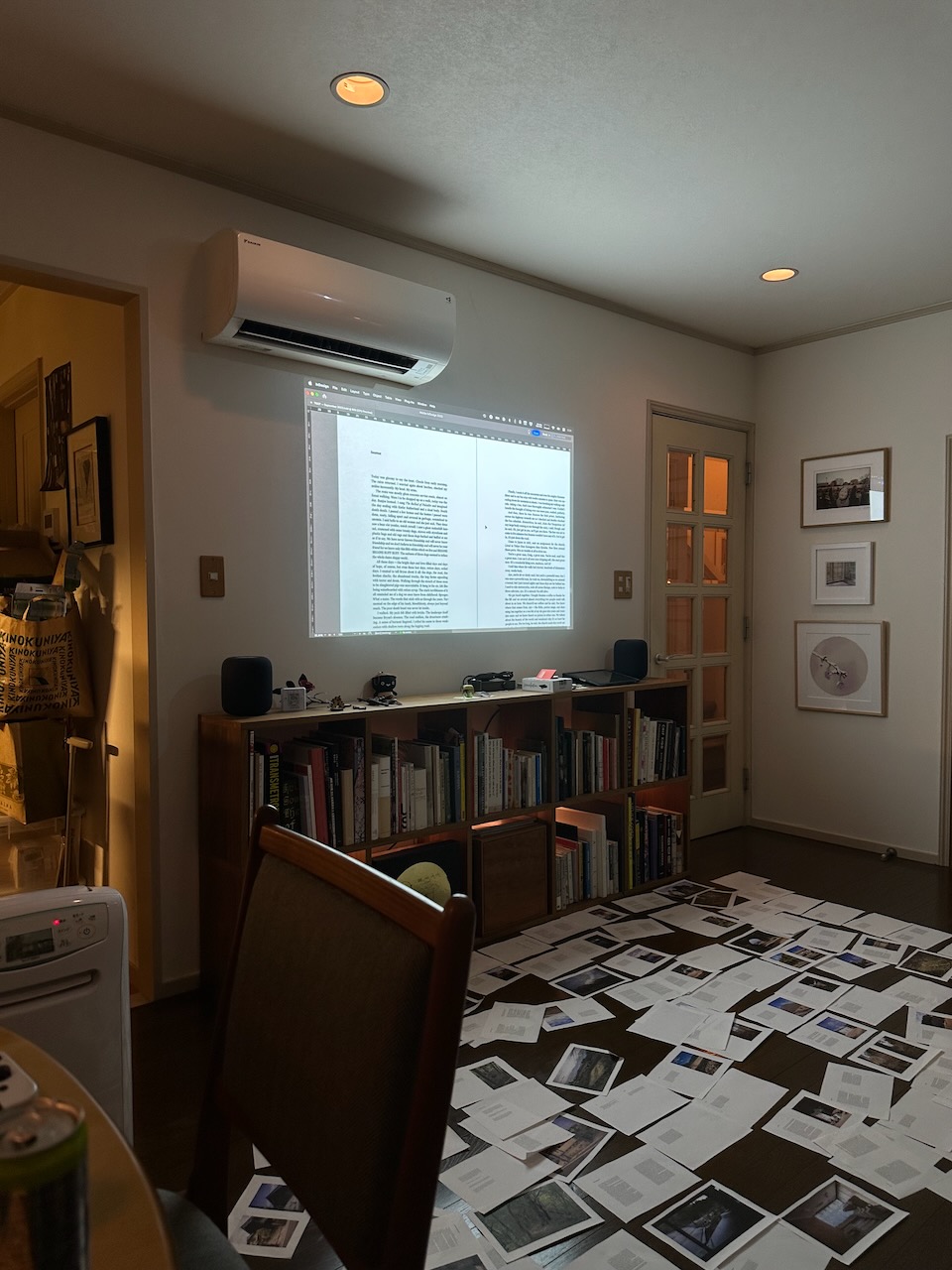

Things Become Other Things became a thing here. Oli Chance, the editor of the fine art edition, flew out (twice) and lived in the tatami room and we worked like mad, day after day for weeks, printing the book out, placing it on the floor, walking over the book, cutting and rewriting as needed, smoking in the garden. Longtime friends David and Carina came down and we projected the book onto the wall here in my living room and proofread the whole damn thing together out loud. (Thanks guys.)

I learned to properly cook here. (Building out / upgrading the kitchen was one of the first pandemic moves I made.) I baked a ridiculous amount of bread. I made too much pizza dough. A couple crazy pizza parties were thrown in the garden. (I should have thrown more.) Love was discovered and nurtured here, family bonds were strengthened here. My parents stayed here the first time they visited Japan. I figured out how to think about and commit to things in ways I had never been able to do before I had moved here. The house taught me much.

Of course, the house was not perfect (it was haunted by mold (as are most places in Kamakura; hence my obsession with ventilation)) and is unbearably hot — increasingly, unlivably so — in the summers because it gets non-stop direct sunlight from morning to night. (For nine months of the year, it’s very cozy; for three it’s … a struggle.) The home, quite frankly, probably needs to be torn down and rebuilt with double-gaze windows and proper insulation. It was built in the Goldilocks zone of the 80s, where it has no historical architectural value and none of the energy efficiency of something newer.

I was rejected by dozens of agents and editors in this house. Felt my fair share of the pangs of abject failure here, and ultimately went through a complex and emotionally crushing breakup here. Which is to say — this place, its walls, contained for me a fullness of life and living I had never before known. And when I think about who I was eight and a half years ago, compared to today — man, a lot of distance has been covered, a lot of days rich and full have been lived.

So it was strange when, last year, I ended up somewhat randomly getting a pied-à-terre in Tokyo. My work increasingly takes me up there (radio, interviews, events; and I loved the city, missed it), and I had been staying at the International House as a member once or twice a week for years. Instead of blowing all this money on a hotel, maybe it made sense to own something? That was the thinking. On a random hunt, I found a cute little space in a great location in an old building on the market for a song. When the quick renovation was finished and the keys were handed over, and I stepped into that tiny jewel-boxy old apartment (the building is nondescript, but was designed by Le Corbusier’s last Japanese student, Suzuki Ren, and as such has small design details and character inconceivable in new buildings), I knew I was done with my old Kamakura studio. (Not that the apartment could replace it outright; it was too small for book work; I can’t overstate how demure it is.) It seemed that a “heaviness of place” had built up in the old house without me knowing it. I stood on my Tokyo balcony and felt like I was breathing full breaths for the first time in a while.

In the last year I’ve spent only three nights in this old house of mine. I feel repelled by it, if that makes sense. I describe the core of the emotion as having “graduated” — from what, I’m not sure. I think it’s the same feeling a lot of artists, writers, musicians have about their work. What’s done is done and it’s time to move on. The house had served its purpose. Sometimes, it’s been time to say saraba longer than you may have realized.

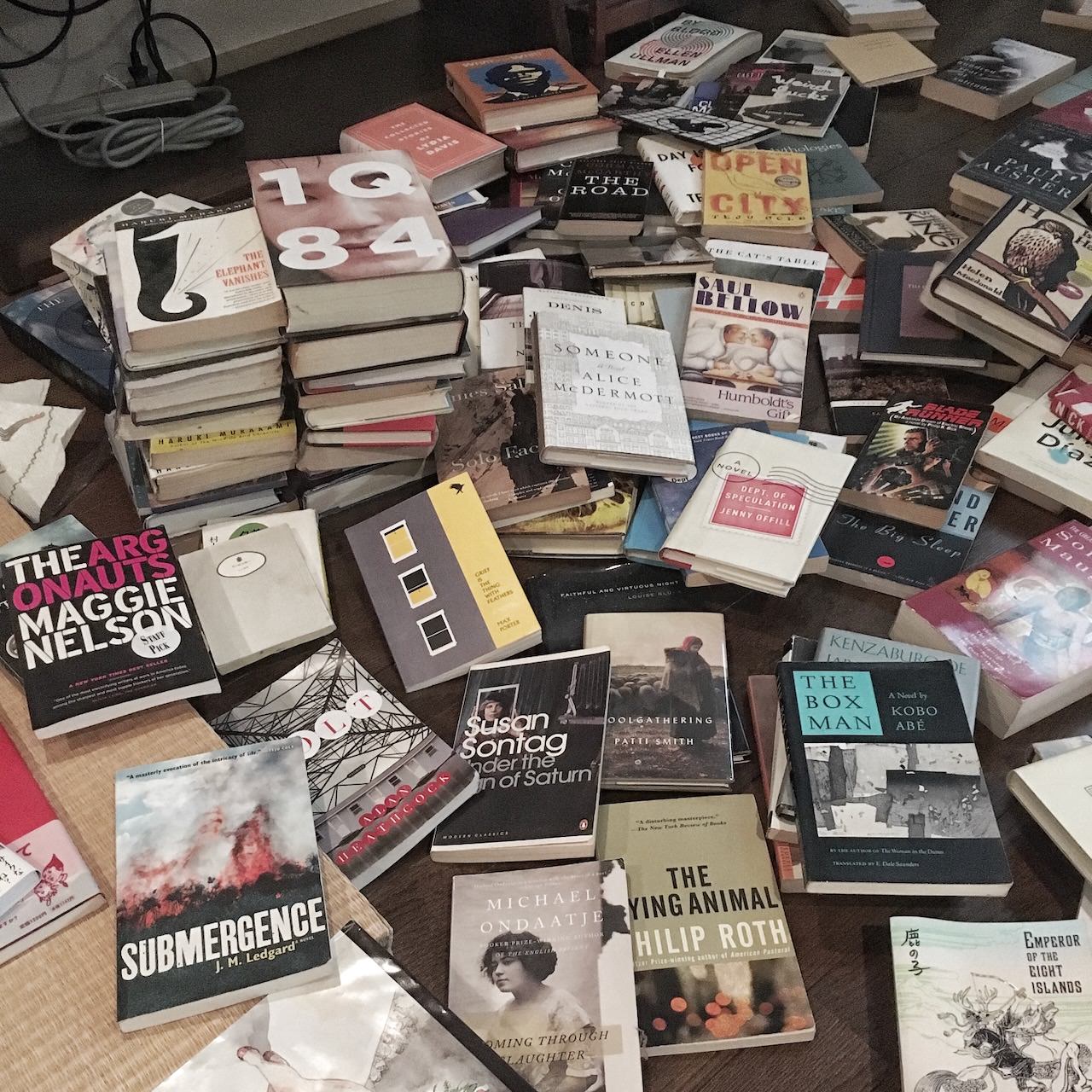

So here we are.1 With packing boxes filling the living room. I spent the afternoon photographing the place, trying to pick up the details, the memories. It’s a mess, but a well-used, working mess. For the last year it’s basically served as a house I lend to friends when they’re in town, and a storage space for all my books and archives (which have grown considerably — I have a lot of “making of” tests and drafts). The blackboard hasn’t been updated in about a year. I’m saying goodbye to this space, a space that changed me for the better, and taught me many unexpected things. A space I’m grateful to have had access too, and grateful for its affordability — which allowed me to continue pursuing projects and books that didn’t have obvious profitable endgames in sight.

Where am I moving all this stuff to? Just across town.2 A friend, whose house I’ve always admired, who had used it well as a place for dinners and parties, for cultivating friendships and making connections, by chance wanted to sell. Timing. I’m turning it into a proper book studio (an entire 5 meter x 3 meter wall has been lined with steel plates and painted with blackboard paint for laying things out / thinking through photographs; I don’t have to sacrifice my living room floor for weeks or months anymore). I’ll have my entire library in my writing space, finally (as opposed to scattered about the house). It has views out over the ocean. It faces a different direction, a kinder direction. The light is gentle. The airflow divine. It’s easy to cool down. Being there makes me feel weightless and full of life, looking out over it all. Mount Fuji is in the distance. It is a place to gather people and collaborate and work on projects bigger than a single person. I’m looking forward to being there, and building things there — naturally books and mapping out walks and recording interviews and livestreams and all that, but also further cementing tenets of love and family and friendship, inspirations and figuring out ways to bring whatever small goodness is possible, into this increasingly weird, off-kilter world of ours.

Anyway, just a public note of gratitude to this old studio of mine, a nondescript house in a sleepy neighborhood, around the corner from a giant Buddha. Thanks, house. Ya did good.

C

Noted

-

I wrote this Ridgeline a couple week ago, before the move. But have since completed the move and wrote about the intensity of the move on Roden. There, I talk about the acute sense of “aloneness” that something like a move can engender. My explanation is probably lacking, but some readers have mistaken my use of “aloneness” as “loneliness,” but it is anything but loneliness. It’s far more existential, that sense of solitude, and the more I engage with the adoption community, the more I realize it may be a pathological condition of adoptees: The sense of forever being “outside the flow” — of the world, the community, your own family; on another track, apart from it all. Some other folks have written in saying, “You know you can pay a moving company to box for you?” but I think one of the greatest assets of moving is the chance to attend to every object you own. Yes, that’s possibly insane, but taking stock of what you “possess” allows you to dispossess the cruft you’ve accrued. Dump / donate / gift the excess. I ended up pruning and purging about a third of everything I owned, and as painful as the boxing was, I’m glad I did it. ↩︎

-

That may sound a bit nuts — “just” across town — in the context of “graduating” from this old house, but the across-town vibe feels like light years away, and the Kamakura area — Shōnan and Enoshima and the Miura Peninsula — hold a dear place in my heart. ↩︎