Overtourism in Japan, and How it Hurts Small Businesses

Why being super popular is not the goal of most small businesses

Ridgeline Transmission 210

Ridgeline subscribers —

I’m Craig Mod and I’ve been buuuuuuurnt out this last month following my epic Things Become Other Things mega book tour. Finally, I’m gingerly emerging from my recovery cave. (But reserve the right to retreat again.) Here’s a fresh dispatch — in praise of small businesses and why overtourism can be anathema to them.

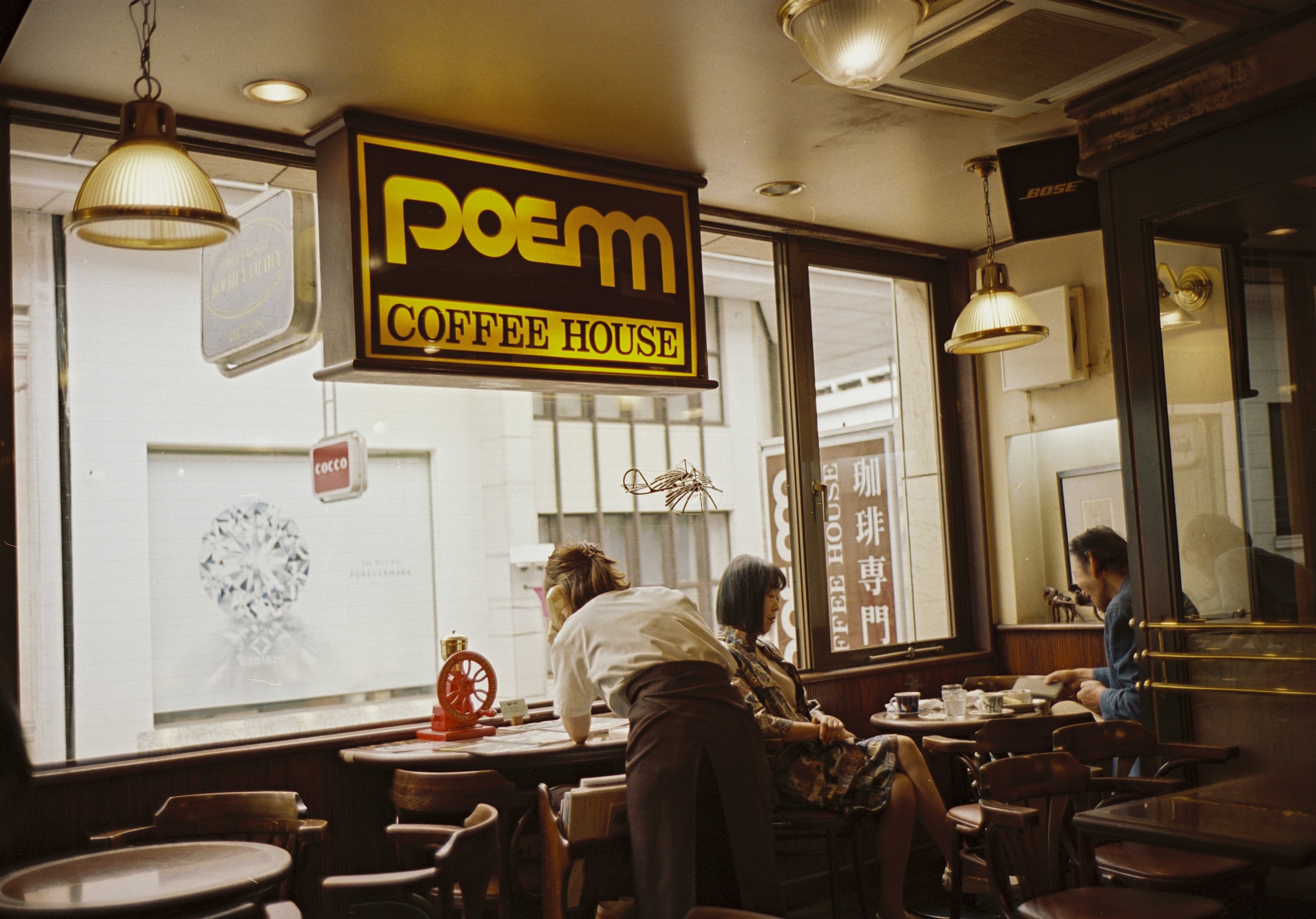

A great city is typified by character and the character of great cities is often built on the bedrock of small businesses. Conversely: Chain shops smooth over the character of cities into anodyne nothingness. Think about a city you love — it’s likely because of walkability, greenery, great architecture, and fun local shops and restaurants. Only psychopaths love Manhattan because of Duane Reade. If you’ve ever wondered why overtourism can be a kind of death for parts of a city (the parts that involve: living there, commuting there, creating a life there) it’s because it paradoxically disincentivizes building small businesses.1 Nobody opens a tiny restaurant or café to be popular on a grand, viral scale. Nor do they open them to become rich.2

So why do people open small shops? For any number of reasons, but my favorite is: They have a strong opinion about how some aspect of a business should be run, and they want to double down on it. For example, forty years ago Terui-san, the owner of jazz kissa Kaiunbashi-no-Johnny’s up in Morioka, was like: Hmm, nobody is spinning wa-jyazu (Japanese jazz),3 so I’m only going to rock it. That led to a bunch of cool knock-on connections, not the least of which was a lifelong friendship with the incredible Akiyoshi Toshiko. That singular thing can drive an initial impulse, but small business purpose quickly shifts into: Being a community hub for a core group of regulars. That — community — is probably the biggest asset of small business ownership. And the quickest way to kill community (perhaps the most valuable gift for running a small business) is to go viral in a damaging way.

Pour out a cold brew for small shops with giant lines of transient tourists. New York magazine just published a scathing/entertaining/hilarious/depressing piece by Reeves Wiedeman on Kyoto’s endemic visitor complications. It’s a city crushed (in parts, but not on the whole)4 by overtourism. This quote jumped out at me:

James told me about another friend who owns a cocktail bar in Kyoto that was TikToked. She had recently stopped by and found him in tears. The only reason he opened the bar, he said, was so locals and friends like her would come. Now, all he had were customers he couldn’t talk to.

That “James” is Maggie James; I’ve known Maggie for nearly twenty years and it’s kind of amazing to see her rip in this article. It seems Wiedeman didn’t censor much. And though Wiedeman tries to pull some optimism out of it all, it’s as dire a portrait as you could imagine of what’s happening to a place of delicacy5 and local charm like Kyoto.

But what can you do if you’re a small business and “get TikToked?” Nothing really.6 Just suck it up and try to find some kind of goodness in the … “weirdness” of “the event” / the happening? Most of these owners have poured much of their life savings into opening these places, taken out loans, put months or years of work into designing and building out their spaces. Years building up regular clientele, forming relationships, knowing what people like, creating true community. It’s not like they can just up and move and hide elsewhere. And why should they have to respond, anyway? It’s tricky to the max, and it’s a problem that never really existed on this scale before social media.7

At risk of oversimplifying: Most “problems” in the world today boil down to scale and abstraction. As scale increases, individuals become more abstract, and humanity and empathy are lost. This happens acutely when the algorithm decides to laser-beam a small shop with a hundred-million views. If you cast a net to that many people, a vast chunk of them will not engage in good faith, let alone take a second to consider the feelings of residents or owners or why the place was built to begin with. Hence: The crush, the selfish crush.

Overtourism brings with it a corollary effect, what I call the “Disneyland flipflop.”8 This happens when visitors fail to see (willfully or not) the place they’re visiting as an actual city with humans living and working and building lives there, but rather as a place flipflopped through the lens of social media into a Disneyland, one to be pillaged commercially, assumed to reset each night for their pleasure, welcoming their transient deluge with open arms. This is most readily evident in, say, the Mario Kart scourge of Tokyo — perhaps one of the most breathtakingly universally-hated tourist activities. I dare you to find a resident who supports these idiots disrupting traffic as the megalopolis attempts to function around them.9

Another oft-cited overtourism example is Kamakura Kokomae — a tiny station on the diminutive, local, Enoden train line, featured in the popular Slam Dunk manga/anime opening credits. The anime gained bonkers levels of traction abroad, and now the Enoden has been rendered nearly unusable for residents (so packed it is all day long). The area around Kamakura Kokomae (a fully residential neighborhood without a single commercial shop; the area gains no economic benefit from the tourists) is filled with tourists lugging giant suitcases (many are only in Japan for a few days amid hot-spot gauntlet runs, sleeping on overnight buses, without hotels to store their luggage at), standing in the middle of the road vying for a selfie. Woe be anyone who lives near that station — their lives exist in an eternal state of disruption.

This overtourism is happening mostly because of algorithms collimating the attention of the masses towards very specific activities / places. There’s also a slightly nutty narcissism / selfish component to it, too — fueling that impulse to, at all costs, “get” a photo at a specific spot to share on a specific social media service. (See: Fushimi Inari.) If the algorithm is the gas, cheapness is the spark. Because, damn, is it cheap to travel these days. Combined with the fact that there have never been more “middle class” people in the world, and you get overtourism. In a way, overtourism complications and disruptions are what happens when “humanity wins” and more people have more time and money to go “do things.”

Japan now gets more visitors in a month than it got in a year twenty years ago. But where are all these people coming from? How has the globe become tumescent with travelers? Well, the world is a lot wealthier today than it was in 2005. China10 is the most stunning example of economic empowerment. In 2000, the country has roughly 30 million “middle class” citizens. Today? Over 500 million. Flying Shanghai to Tokyo takes less than three hours. You can book a three-night-four-day package with flight, hotel, and tours for $500USD on the cheap or $1000 if you want something a bit more fancy. That’s an easy travel ask for a country with as much “cool” as Japan. (The proximity and political stability of Japan also means a lot of “tower mansions” are going up in Tokyo with the explicit purpose of being sold to wealthy Chinese individuals looking for nearby “escape hatches.”) When you’ve only got a couple of days, the purpose of the trip then becomes explicitly about ticking off those social media “must visits” and it’s harder to take a risk or explore off the beaten path.

But explosive middle class or not, the algorithm knows no socioeconomic boundaries. Even the ultra-rich aren’t immune from contorting themselves to “bag the big five” for social cache or status or whatever drives a person to do such a thing. As Wiedeman notes:

Julia Maeda, who runs a high-end travel company in Japan (she recently helped plan a honeymoon for a billionaire’s daughter), said she sometimes struggles with clients who treat a trip to Kyoto like a safari. “You want to bag the big five,” she said. “You want to see the lion and the elephant, and you want to go to the Golden Pavilion and Fushimi Inari,” as well as Arashiyama, Kiyomizu-dera, and Nijo Castle. Maeda often asks clients if they’re “strong enough” to come home from Japan and tell their friends they bagged only one or two. “A lot of people are not strong enough,” she said. “They want the selfies.”

I’ve come to see overtourism as a kind of natural disaster. How can you get angry at the earth for having an earthquake? The mechanisms of capitalism and the American-born ethos of infinite-growth social media (which TikTok simply aped / built atop) have come together to form this demented stew — this blight on cities like Kyoto, Venice, and more — by operating at a scale and level of abstraction beyond human comprehension. Lest life turn into an endless jeremiad, you have to frame it all properly.

Because! Here’s the heartening bit: More people than ever are traveling, and while, sure, the majority of those travelers are just following trends and lists, there is another group, a small cohort of self-aware travelers who are genuinely, deeply curious about the places they’re visiting, who desire to engage directly without being disruptive, who want to engage fully and “authentically” (that is: visiting people and places that haven’t twisted themselves for the sake of transient visitors (i.e., no renaming things “samurai spice”)). And that “small cohort” (let’s say 15% of global travelers) is larger than the total number of travelers the world saw twenty years ago. Omotesando? Gion? They’re lost, like villages washed away by a tsunami. Much like I don’t understand the heart of a wave, I do not understand the hearts of those who come to Japan to buy a Rimowa suitcase. (Quite frankly, it really freaks me out!) And it is not our job to understand.

But that 15% of Best of Class tourists? Every country has them and oh, they’re amazing. And when I recommend a city like Morioka or Yamaguchi or Toyama, I have them explicitly in mind. They are the travelers I want to introduce to these places, and mercifully, they self-select to go to a city like Morioka, a city far from Kyoto (in the opposite direction even). The folks on the quick packages, the folks here to buy fancy suitcases and Rolex watches at a slight discount, the folks who are not brave enough to skip “the big five,” those traveling within a small aperture, a narrow ambit, they won’t adventure beyond, they won’t go to Morioka. (And so in this way these places are insulated from overtourism.) But the lover of all things Japan, the tourist who has studied the language? They go to Morioka. I know because I interview tourists when I’m up there. They always surprise me — in the best possible way. “Oh, this is my 25th visit to Japan,” one Taiwanese visitor told me (he was showing his mom around). A couple had rented a car and were spending a month exploring Tohoku. Another visitor was spending a leisurely week in Morioka alone before heading to Fukuoka for a few months.

These kinds of folks buoy the chest, elevate the soul (like witnessing a person stand on an escalator and just stare into the distance, refusing the Siren call of their smartphone). I don’t know if there’s some Platonic or deontic mode of travel, but in my opinion, the most rewarding point of travelling is: to sit with, and spend time with The Other (even if the place / people aren’t all that different). To go off the beaten track a bit, just a bit, to challenge yourself, to find a nook of quietude, and to try to take home some goodness (a feeling, a moment) you might observe off in the wilds of Iwate or Aomori. That little bundle of goodness, filtered through your own cultural ideals — that’s good globalism at work. With an ultimate goal of doing all this without imposing on or overloading the locals. To being an additive part of the economy (financially and culturally), to commingling with regulars without displacing them.

It is difficult, these days, to glean something from Kiyomizu-dera — a place that demands quiet contemplation and stillness and offers none. Thankfully Japan has a hundred thousand other great temples to visit.

There is tremendous opportunity for a country like Japan — a country with the attention and adoration of the world’s travelers. The opportunity is to redirect that 15% of exceptional, committed tourists, to disperse their positive economic and cultural impact out beyond Kyoto and Hiroshima and Shibuya. Because when visitors and locals connect at a sustainable scale, everyone wins.

As for the overtourism masses? Japan should treat them like an energy source. They are like the winds and rains of a seasonal monsoon, but one controlled and predictable. They contain incredible amounts of wealth to be extracted in exchange for selfies. Japan should consider getting rid of the tax-free shopping program (which causes headaches for residents — it slows down checkouts considerably (thankfully the system is shifting to tax-refund at the airport from November 2026, which should fix this issue)), and should probably charge a higher exit fee (called the “sayonara tax” — currently a whopping $7 USD as of July 2025; they could easily charge double or triple and funnel the additional funds into infrastructure to ease the burden on residents of overtouristed areas). And given the extreme weakness of the Japanese yen, there should probably be local and non-local entrance fees for some of these hotspots.

Paradoxically, despite the numbers of inbound tourists, there’s never been a better time to explore the B-side of Japan. Cities like Yamaguchi and Toyama are eager for visitors and don’t suffer from overtourism. They require a little more work than Kyoto, but the benefits are profound. They are cities composed of incredible networks of small businesses, cafés, and restaurants, forming expressive and unique local textures. They are cities with rich histories. They are close to nature (mountains! old walks!). They are accessible by train. They are walkable and become archetypical for what’s possible outside the mega centers of Japan. They inspire me, and I bet they’d inspire you, too. If you do happen to find a great place, a perfect little hole in the wall, just please do us all a favor: don’t post about it on TikTok.

More soon,

C

Noted:

-

“Small businesses” in our context — the kind that are additive to a city — are those usually opened by individual proprietors with the intent to be in the game for a long while, not chasing some trend. ↩︎

-

It’s simply impossible to “become rich” because of physics. The number of X you can sell in Y hours, given physical space, etcetera is extremely constrained. ↩︎

-

Not only were they not spinning it, they were actively disdainful of it and derided Terui-san for being so wa-jyazu focused. ↩︎

-

Get away from the “big five” and Kyoto is often totally empty and lovely. There is still so much to adore about Kyoto, but feeling like you’re “part of the problem” when visiting is a feeling that’s hard to shake, even if you’re not jockeying for a selfie at the Golden Pavilion. ↩︎

-

Kyoto has always struck me as being so “delicate,” typified by extreme delicacy in manner and construction — wooden everything, small-scale, hyper-codified rules. ↩︎

-

If you’re a landowner with a tree that’s gotten TikToked you can cut it down; a full nose chop to spite the face. If you’re Shizuoka, you can try putting a net up in front of a Lawson. ↩︎

-

That said, some old shops have embraced the tourism crush, the being TikToked. Hekkelun, a stalwart kissa near Shimbashi serves totally normal, totally bog-standard kissa pudding, but for some reason it’s been Endorsed By The Algorithm. The owner has been slinging his pudding for 40+ years. From afar, it looks like maybe — just maybe? — he’s having fun with it? The crazy attention? Maybe being TikToked was an interesting twist in the twilight years of his shop? Anyway, the point being: Sometimes goodness flows, but most of the time, I can’t shake the feeling that the shop owners are in tears. (I’d be in tears.) ↩︎

-

Some small shops that are set up explicitly for overtourism. I consider these a different category of place. They often don’t add to the texture of a city (they don’t provide anything for the community), locals rarely stand in their lines, and they’re usually thinly-veiled attempts to cash in on some trend. For example, matcha lattes have gone nuclear for some reason. (I assume something happened on TikTok?) And so everyone under 30 and their mama is matcha latte bananas. (Taking delicious matcha and focusing only lattes feels … wrong (delicious, yes, but wrong), but I digress.) Like bubble tea ten years ago, matcha latte shops are suddenly popping up everywhere (leading to, of course, a shortage of matcha). ↩︎

-

Perhaps the dreaded SantaCon of NYC is similar? Although that’s only for one night a year. ↩︎

-

China is also salient/fascinating because 25 years ago there were effectively no Chinese tourists anywhere in the world. Today they represent some 25-30% of all tourists in Japan. The rest of Asia has also gotten wealthier. China is followed by South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand, Indonesia, and other East and Southeast Asian countries, together comprising some 70% of all inbound Japan visitors. ↩︎