Smelting and Steel in Photographs

Some behind the scenes photographs for my recent Nytimes piece

Ridgeline Transmission 185

Ridgeline subscribers!

Last week I had a new piece for the New York Times go live: “A Japanese Village Wants Tourists to Come for Heat, Soot and Steel”.

I took tons of photographs (also, this marks the first time for me getting some film-shot photos into the Times, if you’re keeping track / not that this means anything or matters, though.) and, naturally, many didn’t get included. So here we go. This will look a better on my website (vs in your email reader), and you’ll be able to zoom into high-res images, so please click through to read:

Izumo

The trip began in Izumo City, Shimane Prefecture. Stopping by Izumo Taisha, of course, the seminal grand shrine and its misty, photogenic grounds:

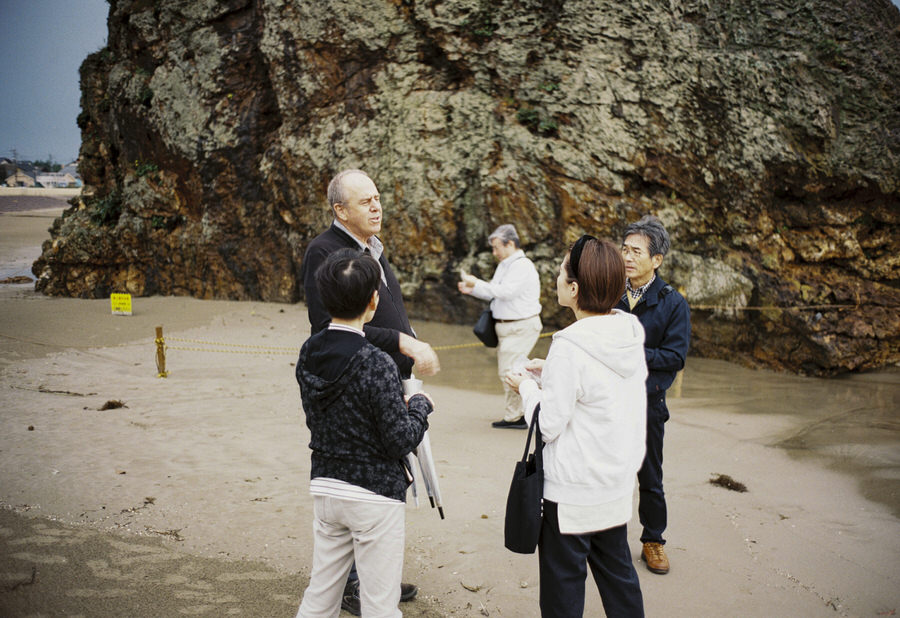

We also swung by Inasa Beach, site to Benten Jima, a registered cultural asset, that was miraculously prophesized in the Nihon Shoki to become an “extremely Instagrammable spot” in several thousand years.

The trip was organized by walking buddy John, who can be seen here confusing a group of random tourists by knowing too much about everything:

Yoshida

From Izumo-shi we drove inland towards Yoshida, to witness the smelting at the smelter.

Some background that was cut from the Times piece:

Yoshida Village and the tataraba are largely run by a single family: The Tanabes. Anzai Nyudo Tanabe first moved there in 1246. In 1460, a Tanabe by the name of Hikozaemon was visited by a deity in a dream: collect iron-rich alluvial soil and smelt it. So said the dream deity. And so began the family’s connection to steel. Today, they’ve diversified by necessity. Tanabe Corporation owns a hospital, a newspaper, a printing company, a broadcasting company, KFC outlets, chicken farms, a frozen food company, a sake business, and a hot spring village to name just a few of their assets. But this is an empire built on tatara steel making. Tatara, Inoue told me, “is our ancestral business, and it is the foundation of many of our current businesses.”

Here are the wheelbarrows that were used to carry out the slag:

And here is some slag slinging in action:

It was all pretty intense, very hot, felt very dangerous. In the middle of the night the first slag removed was also used to cook some mochi rice cakes, an offering to the gods protecting the tataraba and also a nice snack for the workers.

Before it all began the space was blessed:

We also visited an outdoor museum, commemorating the old tataraba, now no longer in operation. This was cut from the Times piece for length:

The furnace we stood before was not an accurate replica of the more ancient tatara furnaces. The last remaining Edo Period smelting structure — Sugaya Tatara — was located nearby, turned into the “Sugaya Tatara Sannai Lifestyle Museum.” Alongside the tataraba runs the clear and serpentine Sugaya River. Outside sits a holy katsura tree, thick-trunked, a tree that is said to love water, and so it is blessed in the Shinto way with a woven rope and paper wreaths, symbolizing both good nearby water sources and with the hope it will keep the inside of the tataraba moisture-free. You can visit them, the tree, the river, the old tataraba. The tourists working the fire had done so. Those old furnaces were built using clay, and destroyed at the end of the three-day fire. Only to be rebuilt again a few days later. The modern tourist-focused furnace we were using was built more sensibly, with safety in mind, composed of interlocking concrete sections that could be lifted by giant winches to reveal the ingot hopefully contained within.

Back in Yoshida, the charcoal and iron-rich sand eventually ran out:

And the winches were deployed and the furnace shell lifted:

This was by far the most terrifying moment of the whole process. If, by chance, the winch slipped, if one of the chains holding the concrete furnace shell broke, and, god forbid, it had landed in that pile of charcoal and slag, well, the entire crowd would have been sprayed with molten lava. I held my breath thinking these morbid thoughts until the furnace was fully moved off and lowered to the side. Finally exhaling, we took it in. The ingot, a kind of nuclear dinosaur turd. The four tourists in spacesuits worked to shovel remaining slag and charcoal to more easily extract the ingot from its hellish birthing space. The crowd cheered. The ingot was brought onto the dirt floor, and we all gathered around it to take a family portrait.

Osaka

Having survived the tatara experience, we concluded the trip with a visit to knife maker, Tanaka Yoshikazu, in the suburbs of Osaka. The Yoshida smelter provides him with some of his steel. His little workshop was shoved between a few homes in a residential neighborhood, and it was all one could do but wonder how the neighbors put up with all the noise and fumes. (His shop was there before it shifted residential, it seems.)

Tanaka-san and his son were lovely and generous and allowed us to mill around the shop for a couple of hours. What a jumble! Beautiful organized chaos and decades-honed craftsmanship.

Here’s Tanaka and his son (who is 47; started at 23 right after college; always planned to take over from pops):

Beautiful, sharp objects were all around, lying in straw and dirt and boxes and well-used hands:

Lots of beautiful light throughout the space:

All in all, a fabulous trip back in October 2023, through I was deep in my TBOT production stresses, and did a final cover check at the onsen/hotel we stayed at in Shimane. (My printer shipped the test covers over; mercifully, they looked great.)

Glad I was able to write up the tatara activities for the Times. What they’re doing is interesting, if not particularly scalable. That said, it can attract (and is attracting) attention to the area.

Izumo-shi itself didn’t strike me as particularly “genki” though — it doesn’t have the vibrating aliveness of cities like Morioka or Yamaguchi or Onomichi or Matsumoto. But it does have a heck of a lot of great history and natural beauty; I hope they can find a way to revive / inject it with some verve.

If you get a chance, consider exploring Shimane, you’ll probably be one of the very few tourists up there.

C