Ebooks for All

Building digital libraries in Ghana with Worldreader

Originally published by: The MessageDoris fired our driver. Again. Doris, Ghanaian, hair braided in tight cornrows, fired one the other day and now fired this one today. I asked her why. She spat, Asking too much! Pennies on the dollar.

You have to understand Doris is a very tiny young woman and all our drivers — standing before their strangely modified Nissan hatchbacks, cars replete with incongruous tiny American flags pasted to the windshields, tattered miniature boxing gloves dangling from their review mirrors, one without a review mirror, replaced instead by a low resolution 8” widescreen LCD panel repeating Jamaican dub music videos from a circuit board and hard drive duct taped to the roof — all these men are double her size. Yet she fires them indiscriminately. They thought they could take advantage of her. You cannot take advantage of Doris. She made one cry.

Don’t worry Mr. Craig, she says. I look worried. Doris Ashrifie is my guide, my linguistic and cultural interpreter; all trip logistics are in her hands. We had only been in Ghana for a few days and I wondered how many drivers this country might have. I was mainly hoping the next car would have shocks. Yesterday’s had shocks.

The drive to the school each morning is nearly an hour and a half. And then an hour and a half back in the late afternoon. The roads are miserable. I’ve traveled atop badly maintained roads the world over and these were hilariously insufferable. All you could do was laugh at their absurdity. War-hardened Martha Gellhorn describes her time driving along the equator across much of Africa in her 1978 memoir, Travels with Myself and Another:

There may be worse roads in the world, but I do not know them. We braced with our feet against the constant jolting, and clung to the sides of the Landrover to keep from breaking our necks at the sudden stops or when negotiating potholes.

I can report: not much has changed. At least she had a Landrover.

The school to which we commute is in a small town called Kade. Population aprox. 16,000. A mining town. A town of dust and rust and corrugated roofing, near-naked children playing in empty dirt fields, a tiny market, and, a digital library.

#Worldreader

Worldreader, headquartered in San Francisco but with offices in Barcelona, Accra, and Nairobi, was co-founded in 2009 by former Amazon.com executive David Risher and Colin McElwee. The genesis of the non-profit was predicated on two simple notions:

- Everyone should have access to books.

- Technological advances are quickly making digital books cheaper and easier to distribute in more scalable ways than physical books.

David and Colin spent a year or so preparing, gathered some Kindles, and in March 2010 went to Ghana to test the idea with twenty students. In his report, David writes:

We came away more convinced than ever that e-readers will change the face of reading in the developing world.

Their most recent annual report, released in June 2014, outlines their 2013 accomplishments, showing just how far they’ve come in three years:

2013 was a monumental year in our growth. Each month, Worldreader provided over 200,000 children, families, and adults in 27 countries in Asia and Africa with hundreds of digital books on e-readers and thousands of digital books on inexpensive phones. As a result, the children, families, and adults whom we serve have read 990,034 digital books in 2013.

In total, Worldreader’s catalog of books offered to the developing world now tops out at 6,699, with an average of 184,000 people reading per month (on ereaders and mobile phones), and a total of 1,784,419 completed books.

I wanted to see some of their accomplishments first hand.

#Bridging interests

In early 2011 I knew not of Worldreader. Back then, while the Kindle was already three years old, it felt like it was finally hitting an inflection point with consumers. It was a thing . My mom bought one. At the time, the iPad was less than a year old. That is to say, the world of mass-market digital books and reading platforms was nascent, and for the most part, those of us thinking about ereading were more focused on how to do cool stuff with their virtual margins rather than consider their effects on, say, developing world education.

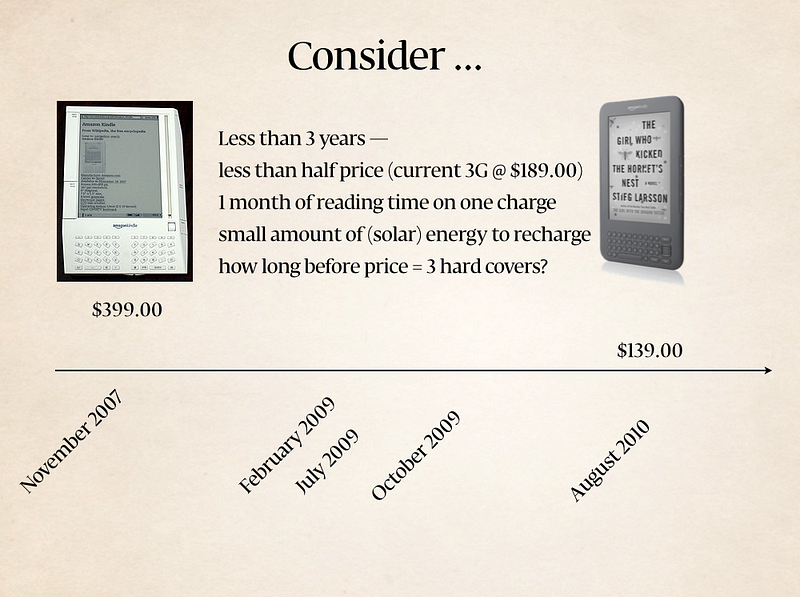

In January of that year I presented a lecture at the School of Visual Arts in New York titled “Post-Artifact Books and Publishing.” Towards the end I projected a slide showing the precipitous drop in price of Amazon’s Kindle e-ink based ereader. In November 2007, the original Kindle debuted at USD $399. By August 2010 the price had dropped to USD $139.

After the talk, I couldn’t stop thinking about that price drop and its potential implications. What happens when the cost of a Kindle reaches zero? What happens when both the distribution cost and cost of the container for books is near zero?

That curiosity led me to discover and reach out to Worldreader. Two years later I was watching Doris terminate our poor drivers, vibrating atop pockmarked roads, spending evenings eating banku with grilled tilapia on a small patio with an ever-so-slight 3G connection, breaking down the day’s work, and ultimately, marveling at the wide-eyed wonder of eager students in a small school in a small village in central southern Ghana.

#Tricks

Obroni is the Twi word for foreigner or, more specifically, white person. Obroni! Obroni! screams every Ghanaian child you pass. Mr. Obroni! Hey hey! Obroni!

Wikipedia tells us it literally translates to “a person from beyond the horizon.” The Urban Dictionary takes us one step further:

Despite the (relatively) widespread and casual use of the word, its origins are not entirely benign. The word “obroni” derives from the word “Abro fuo”, which means trickster, “one who frustrates” or “one who cannot be trusted”.

As Doris and I made our way to the school I couldn’t shake the fear that we were, indeed, tricksters. Well meaning tricksters, but still tricksters. Everywhere in Ghana you see charismatic evangelical churches. A result of obroni, once, long ago, lathering Christianity across the country. Doing so despite the tribes of Ghana having had their own religions, their own spiritual ethos. Yet, those missionaries thought they were saving these folk from themselves, were so sure of their intentions.

Of course, Kindles and Christianity are different beasts. But the fundamental posturing can feel eerily close. Those of us who work in technology tend to take religious-like stances over its ability to change the world, always for the better. My trickster-paranoia comes from an inherent suspicion towards technology, and an even deeper suspicion of presuming to know better. It’s too easy to fall into the first-world trope of “all the poor need is a little sprinkling of silicon and then everything will be fine.” It’s never that simple. Technology is, at best, the tip of the iceberg. A very tiny component of the work that needs to be done in the greater whole of reforming or impacting or increasing accessibility to education, first-world and third-world alike. Technology deployed without infrastructure, without understanding, without administrative or community support, without proper curriculum is nearly worthless. Worse than worthless, even — for it can be destructive, the time and budget spent on the technology eating into more fundamental, more meaningful points of badly needed reform.

The car halted and shimmied around potholes as we inched closer to our destination. We drove through small villages. The children outside — catching a chance glimpse of my face — yelled Hey Obroni! And as the car passed faded posters for upcoming evangelical gatherings, I couldn’t help but think about our own potential for trickery, couldn’t help but wonder if Kindles in the middle of the country were the correct solution to the problems here, or if we were presuming far too much.

#Interstitial digi-books

The e-ink Kindle was, and continues to be, a device seemingly composed of electric fairy dust. It really hit its stride around the fall of 2010, with the release of the svelte keyboard Kindle. This was Amazon’s third-generation of the device and it got almost everything right. In fact, for those of us long-term Kindle lovers, it’s still our favorite version, besting the latest touch screen Paperwhite editions on a number of levels (if for nothing else, those dedicated hardware page turn buttons).

Why was the Kindle (then and still, to some degree, today) so — to reach for that cliché — magical?

- The battery seemed to last forever thanks to the low power consumption of its electronic ink screen.

- The screen really did look like paper that refreshed itself.

- Whispernet: Amazon provided unlimited access to their worldwide 3G network.

- Atop that unlimited 3G network they provided a somewhat hidden, very clunky yet functional web browser that worked in a pinch.

Back in 2011 fellow Messenger, Robin Sloan, wrote up why this third-generation Kindle was, for him, the ultimate travel gadget:

Honestly, even if you are not ever going to read an e-book, but want a device to help you stay connected and organized while traveling—especially if you’re going a bit off the beaten track—the investment in a Kindle (barely more than a hundred bucks at this point) can’t be beat.

Tom Armitage also wrote back then about how the Kindle (in particular, its screen) embodied the philosophy of “quiet tech” — technologies that disappear with their environment:

It was strange to see an electronic device so at home in the physical realm (mainly thanks to that uncanny screen) — and yet the Kindle looks somehow out of place next to more “active” devices such as my laptop, phone, or TV.

It turns out that these qualities — long battery, worldwide subsidized connectivity, a simple screen technology that can take a beating, single-use focus on reading — also make for a pretty good digital library prototyping tool.

#Children and the machines

We arrived at the school a little past ten in the morning. It was a one-story building with a corrugated metal roof and concrete walls painted in fading reds and yellows. The windows had no glass, were simply huge wooden shutters thrown wide open. The floor was dusty concrete. There was no electricity and therefore no lighting.

The headmistress, Jackie Dzifa Abiso, known as Miss Jackie, greeted us outside holding her newborn baby son. I said hello to the baby. He cried. She laughed. “Obroni scary.” I peeked through the window and none of the thirty or so children stirred. All heads down, deep in their ebooks.

The silence was overwhelming and in stark contrast to the volume of everything else I had experienced in Ghana. It had been a long time since I had observed a classroom up close, but I never remembered reading time being quite this quiet.

The Kade children are as children elsewhere: agile with machines. They quickly learn to landscape them, magnify the font size, prop them up like tablets for relaxed reading. They have no trouble with the interface. They make the Kindle do things I didn’t know it could do. The children find hidden features, text-to-voice features, make the devices read to them — robotically but surprisingly clearly — and follow along as the text moves in unison, helping them navigate words that might be a bit out of their English register. Most importantly, the children learn to find books. Books they love, books they must read for homework. Books with curious titles.

This was the world to which Doris and I arrived in Kade. One of heartfelt focus and in which everyone seemed a master of their device. After that first day, my superficial impression was: this might work, this might be a viable solution to a lack of access to literature, this might not be a trick.

Miss Jackie explained to me I was witness to their summer reading session. That the children were of all ages because they were sent voluntarily by their families. And, in fact, today’s class was one of the smallest they’ve had all summer; it was market day, and the parents needed the children’s help.

And what of theft? Here was a small village in which one saw relatively little technology. These Kindles were some of the most advanced consumer devices for dozens of kilometers. Couldn’t they be sold for a tidy profit? When I interviewed Worldreader co-founder Colin McElwee later in Barcelona, he responded, “People don’t steal education.” This seems to have been Worldreader’s experience. That out of nearly 4,000 devices in the field, they’ve had less than a 1 percent loss rate. And even then, it’s suspected that the devices were simply lost — having fallen out of a bag, dropped when taken from a trunk — not stolen. Mr. McElwee also rightly pointed out, Kindles are pretty boring. Unlike an iPad, you can’t play games. They don’t support video. Their single purpose nature makes them unsexy. Combined with the obvious community benefit, that means they’re largely immune from sticky fingers.

#Flip-flopping books

During my two and a half weeks in Ghana I jumped back and forth between Kade and another rural school in a village called Adeiso. I taught daily lessons to the students. I read to them. During breaks they jostled to be photographed. We set up an impromptu photo studio against an outdoor wall. Sometimes I read too slowly, or didn’t finish the lesson quickly enough. Exasperated, a young student would inevitably ask, “Sir, can we please get back to reading on our own?”

And what, exactly, were they reading? Most Worldreader devices contain a mix of western and Ghanaian books. The Ghanaian books are pulled from a cache of more than 300 locally published titles that Worldreader has helped digitize. Many of the books are in English (technically the country’s official language), but many are also in the student’s principal native tongue, Twi.

Some of the more popular titles within their small but potent, locally sourced library are variants on West African oral myths. Books like Twelve Great Anase Stories, published by Ghanaian publisher Sam Woode and The Magic Goat, from Sub-Saharan.

One book, The Bee Ninja, read like a play. I realized that with little effort we could turn it into a film. I had an HD video camera in my pocket (an iPhone 5) and iMovie on my laptop. The next day the students arrived, much to my delight, with a script and costume changes and had mapped out a set between the adjacent dirt field, a tree, and our rectangular school. We filmed the movie on Wednesday. I presented it on Friday using my MacBook Air.

The Kindles worked. That is, there weren’t any technical glitches. The batteries were mostly fine. When a device ran out of juice, they added it to a small but growing pile of those needing a charge. Later in the month they’d be charged in bulk, good for another two to four weeks of use.

What of solar powered cases? In theory, they would be a kind of holy grail — unlimited power for a device that hardly needed any. The school in Kade, in fact, was testing some prototypes. In the end, however it seems the cases proved too unreliable to invest in, ultimately not scalable or cost effective enough.

Instead, Worldreader is now looking for solar powered (renewable energy) stations capable of charging upwards of 50 readers twice a month. The idea being to house them at the schools, with hopefully more reliability and scalability than one-to-one solar cases. They’re rolling out a pilot with a few prototypes in six school this coming September.

In Barcelona, I asked Mr. McElwee about costs. How much did a Kindle set them back? Were they getting them at a discount? He said the Wifi-only model with a case still costs them around USD $100. The case was absolutely necessary. Upon arrival in Ghana you realize you cannot escape the thick dust. It is everywhere. You are covered in it by day’s end; it slithers off you under the drizzle of your shower head. And without a case, it quickly finds its way into the Kindle.

During their first few of years of operation, Worldreader sent back any number of field reports to Amazon, which, in the end, produced Kindles that held up better to the elements. Still, a case adds extra protection, and many of the Kindles currently in the field are two to three years old. Still going strong, in no small part to their cases.

The goal, Mr. McElwee said, is to get the cost-per-device down to USD $50 with case in the next few years. Amortized over a suspected life of five years means a container holding all the books a child may need should only cost USD $10 a year. Less than most paperbacks. (The content, of course, carries additional costs.)

As I flitted back and forth between the schools in Ghana, it’s worth noting that they weren’t without paper. The kids were often handed sheets for drawing, for writing, for solving math problems. As Mr. McElwee summarized: “It’s not that paper is nonexistent — it’s that printing 60 copies of something is nonexistent.” The students have a relationship with paper, but not paper books.

#Goodbye

On my final morning in the countryside I sat at breakfast with Doris and fellow Worldreader employee Alomenu Samuel, or Sammy. Sammy had designed and written my lesson plans, and was helping Worldreader find sustainable ways to scale through western Africa. We talked about my experience over the previous weeks — what went well and what could be improved upon. I reflected back on how most of my suspicions regarding the efficacy of Kindles in Ghana had been assuaged. The students seemed enthralled, and the devices didn’t stutter.

But most importantly, I said, I loved watching Miss Jackie hold forth like a loving taskmaster, accepting no bullshit from the students. That was the key. She ran her classroom decisively, without nonsense or skepticism. You could see that strength inspire the children. That the students read as much and as well as they did was because of her, not because of the Kindles. In fact, I continued (now sitting up in my seat), the most heartening part of the entire operation was how the school and staff were so supportive of the devices, and so obviously eager to foster a culture of literacy and appreciation of literature. You could feel that support bleed beyond the school. Since the children were there voluntarily, so too, by extension, was the community. And that felt very right. In the end, the Kindles were exactly what they were supposed to be and nothing more: containers to get books to children otherwise without.

Tiny Doris’s phone rang. She picked up, scrunched her forehead and burst into a litany of Twi. I looked to Sammy. He shrugged. She hung up the phone. Who was it? She said it was a driver from last week, begging for another chance. And? “I told him I’d think about it,” she said flashing a bright white grin. “See, I’m not always so tough.”

Weeks later in Barcelona, Mr. McElwee would bring up a very good point. “Connectivity is a two-way street,” he said. More and more of the reading happening through Worldreader is not on ereaders but cheap feature phones and smartphones. Devices implicitly connected to the network.

The most exciting part of bringing these students online through reading is that, eventually, “they will become net exporters of their culture.” As Mr. McElwee spoke, I nodded my head, smiling, thinking back on Doris and the rest of the students. Excited for them to transmit their curiosity and humor and worldview back into the greater universe. Yes, while Worldreader is indeed bringing books to those without, in the end, we’ll all read a little differently.