Paju Book City

A city of books on the border of North Korea

Originally published by: California Sunday MagazineAt night Paju Bookcity exhales and its 8,000 workers leave, for there isn’t any real housing here. Most everyone commutes an hour from Seoul aboard a bus referred to as the “infamous” or “nightmarish” No. 2200 due to its long, stressful boarding lines. Employees do not work late in Paju. So by 8 o’clock, Bookcity is yours and yours alone. You walk its five-lane asymmetrical thruways and single-car boulevards and see not another human. You arrive at the head of Gwanginsa Road, named after an old Korean publishing house. The road feels a little clinical in the blue-white fluorescence of the LED streetlights. It is also inexplicably curvy, meandering, considering its utter lack of obstacles. The next day you ask a tour guide why this is so. He responds, “For romance.”

Paju is part of a government effort to revitalize the regions outside of Seoul, in this case with a 1-square-kilometer “city” devoted to “planning, producing, and distributing books by well-intentioned publishers.” Roughly 200 of them are housed here, each in unique quarters, because all of Bookcity’s buildings are different. Unlike in other publishing worlds — New York, for instance, where editors routinely perch 30 or more floors above readers — each structure is built to human scale, none soaring higher than three or four stories. Their size feels just about right. Books, after all, are intensely personal. While you have never before thought about designing a book city, you know now that it should not be filled with skyscrapers.

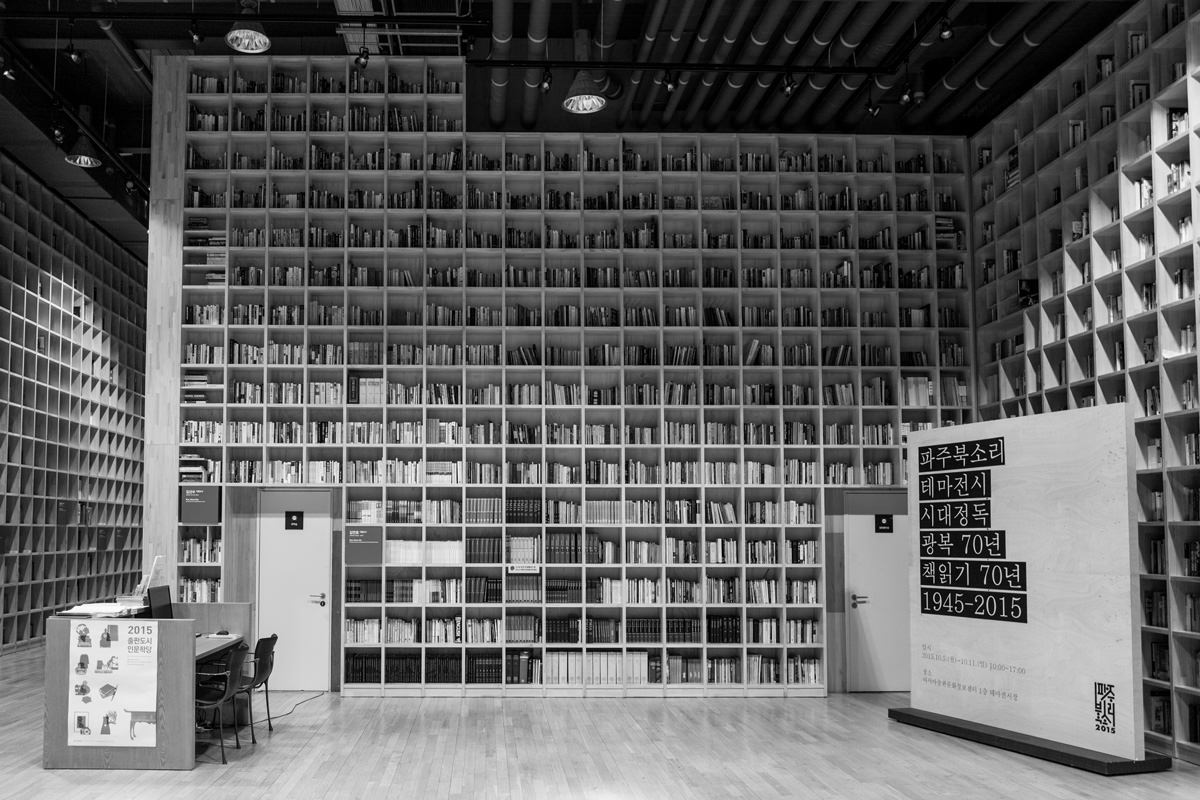

You walk the sleepy roads and Instagram using the zippy and ubiquitous BOOKCITY Wi-Fi, sipping an expertly made Americano held in a coffee cup printed with pictures of books. You pass a shop called Bookcafe Beautiful Peoples, then stroll back to your hotel. It is called a guesthouse, although the Modernist exposed poured concrete and elegant wood defy that humble description. Guesthouse Hotel Jijihyang is a shrine to books. It bursts with novels, dictionaries, manuals. In fact, you have never seen a hotel with so many tall bookshelves. Bookshelves 10, 15 stacks high. “How does one reach those books up top?” you ask a woman at a desk. She explains that the “best books” are on shelves six and lower, so it’s rare anyone needs a high book. Qualifying her comment, she shrugs and gestures to a hydraulic lift covered in dust.

Before you, then, splays the ultimate in books as décor, books as objects, as ends in themselves rather than conduits of art, entertainment, or information. It would not surprise you to return to Bookcity in a few years and see people sitting atop books, eating off books, eating the very books themselves.

Yet it works somehow: the warm lighting, the overflowing shelves, this general sense of bookiness. The guesthouse is a comfortable and inviting place. It welcomes you, as does the city. You feel an almost maternal embrace here, a flood of childhood memories. Books are reflected in the mirrored elevator doors. Books appear in night-lit windows. Books create a landscape possible only with print: No digital collection could evoke such unexpected emotion, even when you don’t speak Korean, can’t read a single title.

You return to your room, within which sits no television. In its place is a plexiglass case with a few old books. Books you can’t touch, books you can’t read, but that are there, in front of your desk, keeping you company in the quiet of Bookcity.