The Leica Q

A six month field test — by Craig Mod

The Leica Q is the best travel camera I’ve ever used.

Over these last six months, the Q joined me while on assignment in South Korea, trekking across Myanmar, hiking the mountains of Shikoku, and spending a few freezing nights on Mt. Kōya. It was used in searing heat, 100% humidity, covered in sweat amid rice fields beneath a relentless sun. And in subzero temples, as candlelit Shinto and Buddhist fire ceremonies ushered in a new year.[1]

I traveled to these places mainly for work. And because I had no plans to return to them soon, I often had but one chance to get the necessary shots. The Q did not disappoint, hiccup, lock up, or stutter. The images in the essay are a testament to its capabilities.

The Q is small but substantial. Solid. It becomes an effortless all-day companion. Strapped across my chest, it was banged sideways against rocks, motorcycles, stone walls, metal water bottles, farmers, cats.[2] It captured everything thrown at it and into it. And while I was suspicious of the value of the camera at first, these past six months have made it clear that this machine has serious legs. I now understand the limitations of this photographic instrument, of which there are few. And I trust and enjoy it more than any other camera I’ve owned.

Yes, even more than my iPhone.

I believe that in hindsight — and I realize this sounds kind of crazy, as if I’ve binge-inhaled all of the Leica Kool-Aid at once — the Leica Q will be seen as one of the greatest fixed-prime-lens travel photography kits of all time.

Fire up the percolator, pour over another single-origin, steep some English Breakfast, or just grab a flask of rye and your pitchforks and let’s deconstruct this beautiful thing.

view 1:1

“Photography is so linked to science that technical explanations are inevitable in any discussion of the esthetics of the camera.” — The History of Photography

Framing the Q: Things that shouldn’t exist

The Q was announced in June 2015, but it has been so popular (according to the Leica NYC store staff, it's the most popular launch they’ve ever seen), people are still on wait lists to get it. It took me three months to get mine.

The Q has a “full-frame” (the equivalent surface area of a single frame of 35mm film) 24.2 megapixel CMOS sensor paired with a fixed, 28mm Leica Summilux f1.7 lens. You can’t remove the lens and it doesn’t zoom so you can only shoot at 28mm. 28mm is similar to the field of view of an iPhone.

view 1:1

Make no mistake: The Q is a surgical, professional machine. It pairs best-of-class modern technology (superb autofocus, an astounding electronic view finder, workable ISOs up to and beyond 10,000, a fast processor, beefy sensor) with a minimalist interface packed into a small body, all swaddled in the iconic industrial design for which Leica has become famous. The result is one of the least obtrusive, most single-minded image-capturing devices I’ve laid hands on.

If the GF1 so many years ago[3] set in motion an entirely new genre of camera with micro four-thirds, the Q epitomizes it. If the iPhone is the perfect everyperson’s mirrorless, then the Q is some specialist miracle. It should not exist. It is one of those unicorn-like consumer products that so nails nearly every aspect of its being — from industrial to software design, from interface to output — that you can’t help but wonder how it clawed its way from the R&D lab. Out of the meetings. Away from the committees. How did it manage to maintain such clarity in its point of view?[4]

Focus — Auto and Manual

The Q’s autofocus is fast and dependable. It makes my other cameras feel downright sluggish. Out of the approximately 8,000 photos I’ve taken over the last six months, only a dozen or so were missed because of improper target lock. I can’t count how many shots would have been missed without autofocus. The scale definitely tips in favor of autofocus.

However! The Q also has a splendid manual focus mode. In fact, this may be the most satisfying manual focus lens I’ve ever used. It’s certainly the best I’ve ever felt on a digital camera.

Manual focus is engaged by pressing an ingenious little tab on the focusing guide ring. This tab unlocks the ring and switches the camera into manual mode. In doing so, the Q merges both the manual focus interface and the engagement switch. It’s a creative and natural combination.

The viewfinder then uses both magnification and focus peaking[5] to make it straightforward to acquire your target, even in near pitch-black, candlelit settings. This also has the added benefit of total discretion — autofocus activates the red focus-assist lamp below a certain lumen threshold. By focusing manually through the electronic viewfinder, and using the silent electronic shutter, the entire contraption operates in total stealth.

I can’t say enough good things about the Q’s manual focus mechanism. I’m smitten. Swooning, even. Of all the little touches on this device, manual focus may be my favorite. Unlike other digital camera manual focus rings, this one has a hard start and stop. It doesn’t keep rotating. There are edges to the mechanism and, from those edges, affordances to the experience. The result is that two meters away is always the same distance in ring rotation. Distance guides can be printed on the lens barrel allowing for dependable street photography zone focusing. As M rangefinder users know, there’s a certain muscle memory that allows for fast, accurate manual focus at shallow depths of field. The Q allows, if you so choose, to develop the same set of muscle intuitions.

view 1:1

Cropping

I’ve never been a cropper. Having grown up photographing with film and spending years developing black and white photos in my university apartment in Philadelphia, cropping has always felt like a hack, a lie. Of course, all photos are lies, all photos are crops. The very definition of a photograph is to add edges to the world, slice off some snippet, place it in a tiny box. Or, as the late Chilean photographer Sergio Larrain put it, “The game [of photography] is to organize the rectangle.”

I realize now that a “perfect” rectangle — pulled back so you see the edges of the negative in the exposed print (to “prove” you haven’t cropped) — is a parlor trick more than anything.

view 1:1

The Q shoots only at 28mm. 28mm is pretty darn wide. And so I’ve found that in the last six months I’ve not only become a cropper, but I relish cropping. In fact, I even crop on the iPhone now, something I’ve never done before.

view 1:1

The quality and resolution of Q sensor data far exceeds what’s needed for most use cases. You can zoom and zoom and crop and crop and the image still feels like archival data.

view 1:1

Of course, you lose the compression coupled with resolution that comes from the optics of a long lens, but you can eke far more play and versatility from this 28mm lens than I first imagined possible. If the thought of a fixed 28mm lens has you on the fence, consider reconsidering.

view 1:1

The Q allows you to shoot in “auto-cropped” 35mm and 50mm modes. This just means that 35mm or 50mm frame lines are presented in the viewfinder and, when you press the shutter, the Q saves the image within those lines, approximating having a 35mm or 50mm lens. Of course, you lose resolution — it doesn’t magically make a 24.2 megapixel 50mm equivalent image.

The Q ships with the frameline switcher mapped to the button most cameras use for exposure lock. This is probably to keep it from wallowing in some purgatory of menu obscurity. Thankfully, the Q allows you to remap that button. One of the first things I did when I got the Q was change it back to exposure lock.

I shot using crop-mode for a few hours but, honestly, it didn’t make much sense. Of all the little touches on this camera, this crop-mode function is the only one that feels like a gimmick. Like some acquiescence to marketing department demands on the part of engineering and design. I find it far more pragmatic and fun to crop after-the-fact in Lightroom or Snapseed. I’m not concerned with precise “35mm” or “50mm” lens mimicry, but rather with the best crop for the image at hand. This philosophy feels like the natural way to approach digital photography — the crop being not only acceptable, but also an intuitive and native part of the digital development process itself. To shoot and not consider cropping is to somehow deny the medium part of what it does best.

view 1:1

Of all the “surprises” I’ve experienced shooting with the Q, this newfound delight in cropping has been the most effecting on the way I shoot and think about images — both before and after the decisive moment. If the prime metaphor for this camera is a scalpel, then the striking thing is that it keeps cutting — finer and finer — long after the image is captured.

view 1:1

Goodies in the dark

“Lately it’s been striking me how I really love what I can’t see in a Photograph.” — Diane Arbus: A Biography

The Q loves shadows. For years I’ve habitually underexposed a few stops to save highlights. Now I do so with even greater relish knowing the Q’s RAW files will allow me to tease out several more stops of detail from the shadows.

Take, for instance, this image from New Year's Eve. I captured it as I ran alongside men carrying a giant burning torch towards a Shinto shrine for a pre-midnight ritual:

view 1:1

The details revealed are subtle but absorbing; we keep the energy and structure of the flame but also gain a bit of context: The stone lamp becomes a fully fledged object, the men below and aside the flame visible. Will they ignite themselves? We don't know. But now we can ponder it because we can see them. And that brush of spotlight upon the waterman’s shoe? A nice little twinkle in the corner.

Do hulking Nikons and Canon perform similarly? Probably. Are they as easy to carry, minimal in interface, and as joyful to use as the Q? Probably not.

Intermission #1: Storytime — A family

Do you see this photo below? This family? It was my birthday. Our first day in the field. We were led through rice paddies in the countryside of Burma. This way, he said, the man who arranged the interviews for our work. We were there for work. But what’s important is this family.

view 1:1

It was my birthday, you see. I had been sick, was still sick. And there is a certain brand of melancholy that descends only with sickness. A feeling amplified by a foreign setting, far from typical comforts. You feel vulnerable. Compounded by an overly dramatic, borderline ridiculous, fatalistic certainty that it will end (your birthday, the cold, life itself), that you are fallible, certainly not invincible. And that’s OK. I was in that fragile state on this day, my birthday, in the rice fields of Burma.

We spoke with the head of this family for an hour and a half. Two hours. Part of the ritual of the work was to photograph them at the end. To take a snapshot. A memento that would be printed and returned to them as a token of gratitude.

Here we were, in a room without electricity. Their home. And they all sat facing the slanting late afternoon light of the early Burmese summer crop season. The father is in the doorway, shirtless. He laughs. I photographed. Everyone was present. They were glad we were there. We were happy to have gotten their time. I felt my ailments lift, a little strength return. They were full of a love. A love we received. And although there was hesitation at first — rightful suspicion (you can still see it in the mother’s eyes; she gives this many shits: zero) — through translation we found common ground. Can you see that? I just puffed my cheeks and pulled my ear like a monkey behind the camera, which is not attached to my face, but rather held a bit below. The little girl laughs. She broke her arm riding a bicycle through the fields. Snap. This picture emerges. A perfect birthday present.

Video

I think the Q does video.

Battery

I bought an additional battery but I’ve never needed to use it in the field.[6] I’ve done full-day shoots of 300+ images and the battery has gone low, but never to zero. Still, it makes sense — if only for peace of mind — to carry an extra. You can even buy Panasonic branded ones identical to Leica’s and save some money.

Unfortunately the Q does not allow for charging via USB. Meaning: You must carry around an external battery charger as you romp through the world. You can, however, hack your charger using Apple’s power adaptor plugs to avoid having to also carry a cable. I hope that Leica is able to add charging via USB in a future firmware update, but I fear it might be impossible.

view 1:1

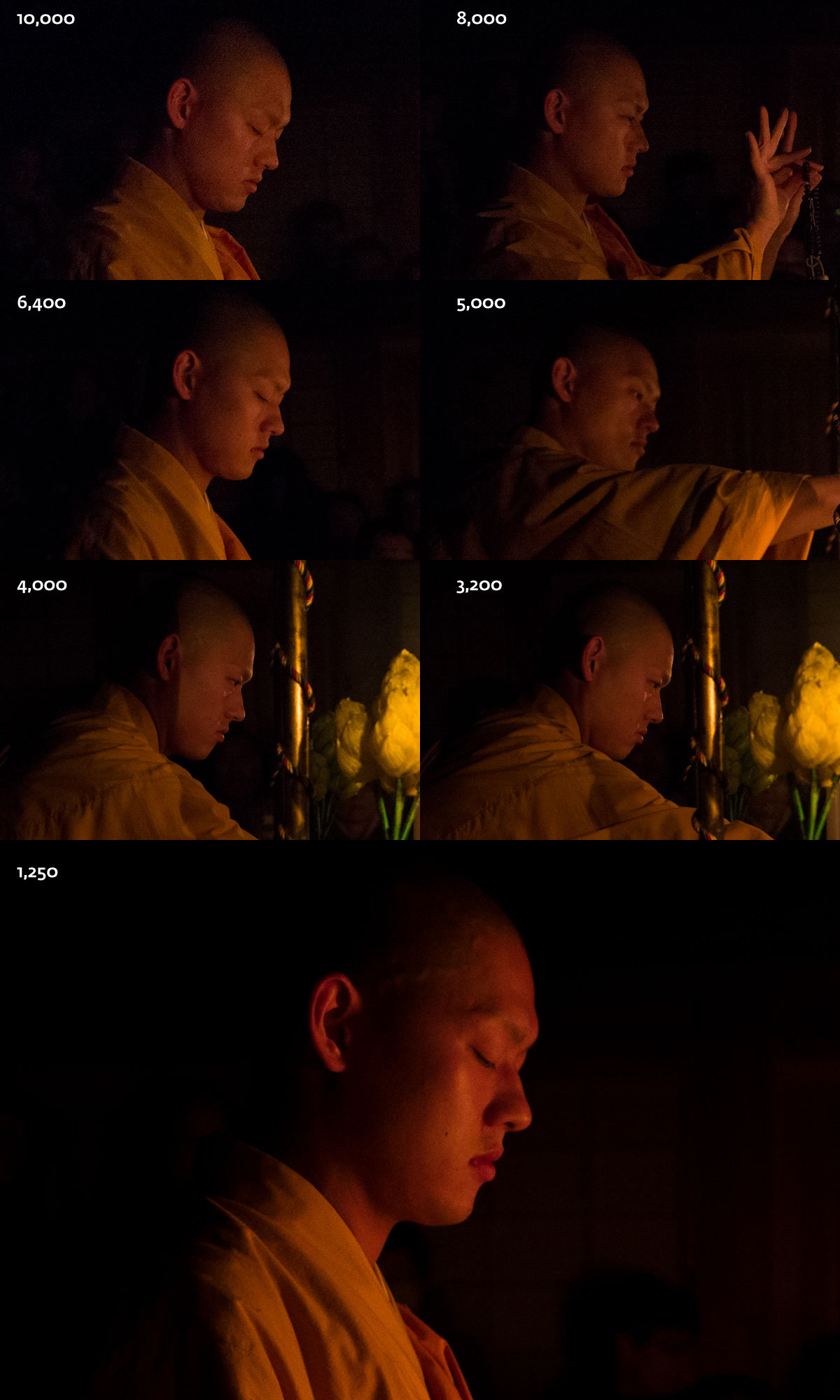

10,000 ISO

The Q is the first camera I’ve felt comfortable pushing past 3,200 ISO. But I wasn’t comfortable initially. In fact, for the first two months, I shot only with its auto-ISO set to 3,200 max at a minimum shutter of 1/60th of a second. Boy, was I missing out.

I now shoot with the Q maxed at 10,000 ISO and the shutter low-capped at 1/120th of a second. You almost never need 10,000 ISO. Technically, the Q maxes out at an absurd 50,000 ISO. I've never used it. I find the camera rarely breaches 6,400, and I do a lot of lowlight shooting. But when it needs the extra bump, it’s nice to have. The ISO 6,400 Q images are wholly usable. And images taken at 10,000 — if needed — work.

Additionally, 1/60th of a second is quite slow. And by shooting at it, you're opening yourself up to motion blur or camera shake. I find that by forcing a minimum of 1/120th of a second means almost no lost shots. And because the Q has such capable high-ISO, I don’t mind trading low ISO for higher-speed shutters.

On New Year’s Eve, during a goma taki fire ceremony at Eikoin Temple, I shot from 10,000 ISO down to 1,250 ISO, all of the same scene:

view 1:1

I love this final shot of the sequence, if only because it embodies all the goodness of the Q. To avoid focus-assist lamps going off, the shot was focused manually, through the electronic viewfinder, cropped, and taken without concern towards ISO (it just happened to have worked its way back down to 1,250 by this point). It’s the kind of image you can pull from a system that gets out of the way, doesn’t perturb those around you, and lets you focus on what’s happening in front of your eyes.

Here’s the full sequence zoomed into the monk’s head so you can more easily compare ISO quality:

WiFi and Remote App

Surprisingly,[7] the WiFi functionality and remote iPhone Leica app work extremely well. The Q becomes the network host and the iPhone the client. Once configured, going from having taken a photo to starting the WiFi, loading the app, downloading the photo, and having it on your iPhone can happen in as little as twenty seconds. It’s really quite fast. And batch transfers work well, too.

The remote operational functionality is also well-implemented (one by-product of which is the removal of the remote threads from the shutter button; this sadly means no fun with fancy soft release buttons). Lag between Q and iPhone is minimal, and you have almost complete control over the camera. I’ve played with the remote only a few times so I don’t know what kind of range (typical WiFi range, I assume, as that’s what the connection is based on) it gets, but it seems to do what it says on the box with little fuss and a lot of fun.

view 1:1

The lens

When you buy the Q you’re buying mainly a lens. Heck, most of the interface for the camera is on the lens — aperture control, auto/manual focus toggle, switching between macro and normal modes.

It's worth taking a second to emphasize this point: 99% of the interface is on the lens. Once you configure your auto ISO settings, you almost never have to touch the back of the camera. Twist for aperture. Toggle manual focus. Press the shutter release. Everything else takes care of itself. This interface minimalism is a big part of what makes the Q such a pleasure to use.

I’ve spent most of my adult life shooting with 35mm or 40mm (the GF1 20mm pancake) or 50mm lenses. In contrast, the 28mm f1.7 lens on the Q feels wide at the outset. But once you settle into the Q's field of view, it becomes a comfortable and, dare I say, satisfying place to live. (And because, technically, if you’ve been shooting with an iPhone you’ve been shooting at 28mm; it’s doesn’t take long to feel out its edges.)

view 1:1

On the rear of the lens is a ring that rotates to shift the camera into macro mode. I rarely, if ever, feel inclined to shoot macro so I haven’t used it much. But for spontaneous lichen observation or other nature-walk related close-up photography, it’s a boon to have right there. And the ring is positioned in such a way as to be easily ignored if you never need it.

view 1:1

The lens is cinematic. Were it topped out at f2 or f2.4, I don’t think the effect would be as pronounced. But because the Q’s 28mm opens to f1.7, you’re able to achieve what I can only describe as voyeuristic cinema. The satisfying color rendition of the Summilux and shallow depth of field — even at distance, perhaps especially at distance — combined with the almost always accurate autofocus, collude to produce otherworldly (or, hyperworldly) scenes as if lifted from a film. I’ve grown to love the subtle qualities of these images. I suppose this is the so-called Leica feel everyone talks about. Over time, you learn to use both a combination of light and sharpness to guide the eye in a way that isn’t possible (without more work) on the iPhone.

view 1:1

view 1:1

The shutter on the Q operates in either in super-quiet leaf mode, or total-silence electronic mode. The leaf mode tops out at 1/2000 of a second, switching automatically into electronic which tops out at 1/16000 of a second. Why have both? Well, for example — a leaf shutter won’t suffer from the “rolling shutter” of electronic shutters. Rolling shutter causes photos taken out of moving vehicles to look skewed. With a leaf, everything lines up just right. And, anyway, it’s pleasing to hear a little mechanical thunk when you take a picture.

view 1:1

The Q’s fast lens benefits greatly from the camera’s electronic shutter. It allows you to keep the lens wide open no matter how much light may be in the scene. The practical application of this is broad-daylight captures that would be otherwise uncapturable, where the focus is on the subject and the bright world beyond is thrown into buttery bokeh. This kind of shooting is effectively impossible on the M series of Leicas and most other cameras without electronic shutters, due to insufficient shutter speeds and too much light reaching the sensor.[8]

view 1:1

The lens hood also deserves some attention. The octagonal metal hood doesn’t clamp or clip on, but instead threads itself in such a way as to always perfectly align in parallel with the lines of the camera. I’ve never worried about knocking it off or it working lose. It’s on tight.

I use the hood in conjunction with a B+W clear filter. This means I’ve never used the Q’s lens cap (even though it’s precisely designed to fit snugly over the hood) — there’s simply no reason. I wrap the camera in an old tenugui rag if I’m throwing it in a bag, otherwise, I keep the hood on, the cap off, and the camera at the ready.

view 1:1

Intermission #2: Why I photograph

I’m not a fine-art photographer. I treat photography as a process of record-keeping. Sometimes, if I’m lucky, the records are beautiful. I’m not romantic about my tools (although I do find romance in them!). I’m delighted to discard something if I find a better solution. I have little brand loyalty. I like to contradict myself over time as industries evolve.

Over the last seventeen years I’ve shot travel and street photography with the Nikon n4004s, the Nikon FM3a, one of the original Sony Cybershots (the DSC-F505V), some early Fuji digital point-and-shoots (still some of the most magical out-of-camera color rendition IMO), and a Nikon D70. I’ve shot in the studio with my Hasselblad 500C. I’ve done some big treks with the Panasonic GF1 and GX1. I’ve used a Canon 5D Mark III extensively for a couple days; it’s a tank, but not one I'd want to lug around every day. Earlier in 2015 I used the Fuji X100T for three weeks but wasn’t impressed enough to write about it.[9]

Of these last twenty years, I believe with all my heart that the smartphone has emerged as our most important photographic tool. Absolutely the most important tool in terms of abject democratization and access to photography. Combined with always-on networking, and the right platforms, it forms the core of giving everyone in the world — especially those in emerging economies for whom a camera is an impossible purchase, but a smartphone is now a necessity — the ability to embrace photography in whatever way they deem fit. That’s a special thing, and one not easily dismissed.

I love shooting with the iPhone. It’s satisfying for so many reasons: It’s always in your pocket, it’s quick to turn on, the screen is gorgeous, the touchscreen feel is unrivaled, and every year it gets incrementally better. Unsurprisingly, active research and development as writ over eight years yields an exceptionally capable camera, networked, with great GPS data. If you see photography from a certain kind of angle — one of reportage or memory enhancement, substance first and style second, where beauty is a wonderful corollary to capturing the story — then the iPhone is an unbeatable tool. All other photographic tools on the market must justify their place within this context.

I’m intrigued by the various complex chemical processes of photographic development, but have long since given up shooting or developing film. I like the straightforward nature of digital and shoot only RAW (when I’m not using my iPhone). I process my photos mainly in Lightroom, but sometimes using WiFi transfer to Snapseed on iOS. I’m intoxicated by the immediacy of response on Instagram and Facebook and Twitter. But I also enjoy a languid edit with an eye towards a tactile, evocative, printed thing. I’ve been an author and designer for the last fifteen years and obsess over the particulars of thoughtfully made tools — especially the tiny details and margins of objects that conspire to create a great experience, be they in the balance of whitespace in a book or the tension and haptics of an old brass doorknob.

Aesthetics and handfeel and typography

The Q is handsome. It’s comfortable to hold all day and demands to be picked up again and again. The classic Leica M series of rangefinder is an obvious antecedent to the Q, and it’s from the M that the Q draws inspiration for its lighter and stealthier profile. The Q’s build quality feels trustworthy, with little shimmy or shake in any of its myriad points of hardware interface. The only rattle is of the optical image stabilizer when the camera’s turned off.

I added the gorgeously machined Thumbs Up accessory to my Q because I like having a firm grip on my cameras. It’s an exquisite little accessory. Made by a guy named Tim Isaac, and ships in a tiny foam-molded box, with a Buddhist-like good luck charm. How can you not like that?

When shooting on hikes I sling the Q diagonally across my chest. When shooting in cities I wrap its leather strap around my wrist and lock it into my palm.

The Q — like most recent Leicas — is engraved with the softly geometric, proprietary LG 1050 typeface. It feels so, totally, completely at home, stamped into the camera body in all caps. It's highly legible and precisely designed. Minimal, functional, but with a bit of quirky character. Like the Q itself. This is the perfect camera typeface used in the perfect way. Mic dropped. Case closed.

And yet, I covered up most of it with black electrical tape. Here’s the thing: I don’t need to advertise what I'm carrying. My blue-collar upbringing induces hand wringing and cringing and hemming and hawing when it comes to so-called “luxury” items. Considering Fuji and other camera makers have effectively appropriated the Leica rangefinder “body look,” if you cover up the red dot, and remove all evidence of it being a Leica, then it mercifully ceases to be a Leica.

view 1:1

view 1:1

Upbringing, safety, and issues of luxury showboating aside, I find the Q simply looks more elegant without the type or red dots on the body: Black and stealthy, no posturing, all the better with which to take pictures inconspicuously.

view 1:1

Quibbles

Contrary to the picture I’ve painted in this field test, the Q is not all roses. Here, I present a list of improvements I'd love to see either via firmware updates or in a future version of the camera. And I do so acknowledging just how much work has gone into this product, and with the utmost respect for those behind it. Admittedly, a lot of these are nit-picky but still, I hope, worth considering:

- Weather Sealing: It’s unbelievable that the Q isn’t weather sealed. This is an affront to the entire essence of this camera — which is to be taken out on adventures, wrapped around the body, pulled up at those precise moments when needed, and otherwise thrown back to be bumped and smacked into the world without worry. Certainly to not worry about humidity or rain. I’ve sweat all over mine, taken it out into drizzles, and dropped it in the snow. It still works, but always in the back of my mind is the fear that something will go wrong. I hope this is fixed in subsequent product refresh. A camera this good should not have to be coddled.

- The jingle jangle of the Optical Image Stabilization dingleberry when the camera is off: Apparently this can’t be helped, but it subtly undermines the otherwise block-of-solid-metal feeling the object exudes. Like a tiny screw loose in the works of a giant clock, you want to pull it apart and find the culprit.

- Video record button: I find myself rarely needing or wanting to record video. Yet I have to live with the video record button as a first-class top-of-the-camera interface citizen. In much the same way we are able to remap the crop-mode to exposure lock, I'd love to remap the video button to WiFi mode. This should be easy to fix in firmware.

- Plastic: The plastic doors to the mini-HDMI and USB ports, and battery and SD card — they feel out of place on this body.

- Touch screen: In six months I haven’t found a compelling reason to use the touch screen — it’s laggy and imprecise. I'd rather it not be touch sensitive as to avoid accidental taps. The hardware buttons and dials work wonders for navigating and previewing images. There’s really no reason for touch on a device like this.[10]

- The battery charger: It drives me nuts. Most other cameras allow you to charge via USB, and this is a great example of Leica dropping the ball on a simple, exceptionally useful technical feature. Carrying an extra battery charger while traveling is a burden, especially when you're hiking and need to pack light. USB charging also means you can charge using external batteries in the field (with an Anker battery pack, for example) — something not possible with a wall charger. All in all, it’s a shame that the Q is stuck in the past when it comes to this feature. Fingers crossed they can fix this with firmware but I suspect it'll require a hardware refresh.

- The ON/OFF continuous / single shot switch: Decades and decades ago, Apple desktop designers made the astute decision to stick the menu bar to the top of the screen. This bestows the menu bar with a unique attribute: It is effortless to click. You simply “throw” your mouse up and you will always land on the menu bar. Contrast with Windows, for example, where the menu bar is fixed to each window, floating, requiring a certain pin-point precision to hit. The Q’s power switch feels a bit like Windows to me. It has three modes: OFF, S, and C. S is for single-shot mode, and C is for continuous-shot mode. 99.99% of the time I want S mode. C mode on the Q is so good (10fps!) that it’s almost impossible to take only a single photo when using it. And yet it’s easier to quickly turn the camera on into C mode than S mode because C sits at the “edge” of the interface. C is at the “top” of the screen. There is no precision required to choose C, but S — plopped in the middle — requires delicacy. Exactitude. Twist too much and you're in C, not enough and you're still in OFF. I admit, this sounds slightly insane, but the ON/OFF switch is a primary interface element, and bestowing it — in whatever ways possible — with more “solidity” can only be a good thing. If you like to shoot in C, then it’s perfectly designed. For me, my heart sinks just a fraction of a micron each time I turn the thing on.

view 1:1

Final thoughts

A product has to earn its place in the world. Especially a product that’s being commoditized and attacked from all sides. It has to function not only at absolute peak performance (in this case, infallibly take great photos), but it has to do so while simultaneously delighting us. I’m a stickler for that: the delight.

The contemporary camera market is such that lots of kits operate at this so-called point of peak performance. But are they fun? Joyful to use? Are they light enough to carry with you all day without feeling burdened, but heavy enough to feel substantial, to take a beating? To depend on?

And what is delight? For me, delight is born from a tool’s intuitiveness. Things just working without much thought or fiddling. Delight is a simple menu system you almost never have to use. Delight is a well-balanced weight on the shoulder, in the hand. Delight is the just-right tension on the aperture ring between stops. Delight is a single battery lasting all day. Delight is being able to knock out a 10,000 ISO image and know it'll be usable. Delight is extracting gorgeous details from the cloak of shadows. Delight is firing off a number of shots without having to wait for the buffer to catch up. Delight is constraints, joyfully embraced.

The Q feels like it’s created from delight itself. The camera is minimal, intuitive, and imposes little compromise to deliver great images. Images that stand toe-to-toe with heavier, clunkier, far less mobile, “professional” kits. Those behind this tool deserve recognition. Especially Vincent Laine, the lead designer of the Q. This is apparently the first camera he’s worked on for Leica. If Leica can find and retain talent like Mr. Laine, then they have a fine future, indeed.

On a macro, industry-wide level, Mr. Laine and his team have struck an impressive balance between not over-technosizing the Q and also not leaning too hard on the anachronistic legacy of the M. Next to the Q, Leica’s other offerings now seem a bit lost — For whom is the touchscreen-only T? The waterproof X-U?[11] The Q, on the other hand, with its lightning autofocus, gorgeous Summilux lens, and fast electronic brains and viewfinder, all built atop the granite-set soul of an M, feels like the arrival of a Leica — indeed, a refinement on an entire class of full-frame cameras — many of us have been waiting for.

If you’re looking for a stripped-down kit — one body, one lens — that will bring home remarkable pictures every time, then this is it. The Q is an unbeatable companion. One I hope to be adventuring with for a long time to come.

Thanks for reading.

Follow me on Instagram for more Leica Q shots.

Thoughts? Spelling error? Egregious logic gap?

Email me@craigmod.com

view 1:1

Recommended

Postscript

This was not a studio test. Not an afternoon walk-about test. Not a weekend lender test. This was a field test. Which means the Q came out with me into the so-called real world, was part of my life under no auspices of clinical examination or safe environment. In short: I used the thing, this is how it felt.

If you can’t tell, I had a blast — both with the camera and the writing and designing of this essay. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I began taking notes months ago, assuming my enthusiasm would peter out. But, no! It only grew. I can’t spill 8,000 words and spend weeks designing an article unless I’m driven by maniacal inspiration. This camera lit me on fire. All the more potent taking into consideration my disavowment (in The New Yorker, no less) of cameras just a scant two years back. Two years ago the landscape felt dismal and the iPhone increasingly — and excitingly — formidable. Today, I still think the iPhone is special, magical, even. But this Q — more than anything Sony or Fuji have on offer — feels like something that shouldn’t exist. The best kind of aberration in the market and, well, it demanded some attention.

All of the photos in this field test were taken by me between September 2015 and February 2016. Many have been cropped. Most have been processed lightly in Lightroom (exposure and white balance tweaks, clarity, levels). There is a 1:1 example detail view link in the description of each image. But this writeup isn’t about pixels, it’s about feel and experience.

And, finally, in the last few months, a few of these Q photos have been published in The Atlantic and California Sunday Magazine. Take a peek.

Noted:

- I fully realize this reads like a parody: I took the Q with me shooting elk from a helicopter, on my ice barge traversing the North Pole, while meditating with hibernating bears. But, the reason I splurged on the Q (and, let’s be clear, this was most definitely the most money I’ve ever spent on a single object outside of a car and Leica didn’t pay me a cent or loan me the camera to review this thing) was because I had such an unusually textured and dense set of work-related travel on the horizon. I mean, I try to optimize for curious adventures that pay for themselves, but these last six months were an aberration even for me. I figured — hell, if I’m going to buy this thing, I might as well do it now and use it to maximally document this collection of experiences. But, yes, I know, I know: parody-esque. ↩

- The cat was an accident. (Well, and the farmer, too.) And then it bit me. (The cat, not the farmer.) So I guess we were even in the end. ↩

- The GF1 was so very special — it was a miniaturization of the DSLR while sacrificing only a bit of visual panache. It felt new — not like a pocket point-and-shoot, but something more capable. The lenses were cute but powerful. A valid bridge, then, between a smartphone camera (which was photographically underwhelming in 2009) and a “professional” camera. The big surprise was just how professional those micro four-thirds images could look. But, in hindsight, it feels like Panasonic had no idea why the GF1 was so popular. Based on marketing in Tokyo at the time and the tenor of their followups, the GF1 seemed meant mainly for some imagined Japanese female consumer who wanted a dainty camera, not for the geeky boys and girls that embraced and joyfully hacked and extended its lovely constraints. ↩

- One could, for example, imagine a worry or tension within Leica of the Q cannibalizing M sales. But, really, anyone who wants an M and can afford the $10,000+ USD investment into the M system is not only not going to be seduced by the Q (probably), but will wholeheartedly reject it as an affront to their own photographic philosophies. Will say autofocus is antithetical to the Leica experience. Will complain about the single lens. One does not buy a $10,000 camera without hard-and-fast opinions. And so worrying that the Q (and I realize I’m just hypothesizing this concern) will eat into M feels largely nonsensical. That said — Do I think this Q points to the starting point of a certain curious, potential future within Leica? ... absolutely. ↩

- Focus Peaking is an in-camera implementation of edge detection algorithms that help emphasize the parts of a scene which are in focus. As you manually shift the point of focus, a laser-like red or white or blue shimmer attaches itself to the various edges allowing you to quickly and confidently know what you’ve locked on to. This is especially useful in darker scenes and, paired with magnification, in many ways makes electronic viewfinders superior to optical ones for manual focusing. ↩

- This includes daylong hikes in -5°C where my iPhone stopped working because the battery got so cold. ↩

- I don’t say this pejoratively, but simply because so few camera-companion apps impress. I’ve played extensively with Fuji’s and it’s thoroughly underwhelming. I had limited experience with Sony’s in early 2015 and it wasn’t anything special. And so to see Leica — Leica! — a company that isn’t known for being technologically progressive, deliver a simple, functional, reliable, and stable app is a true delight. ↩

- You can always layer [Neutral Density](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neutral-density_filter) (ND) filters over the lens, of course, but the immediacy and seamless engagement of the electronic shutter is a mighty tool in the kit. (Also, hilariously, the photo of the farmer above was shot at 1/2000 a second — using the mechanical shutter. For some reason I had always assumed it took advantage of the electronic shutter. For an example of something that only an electronic shutter could capture, take a peek at the shrine dog photo up above.) ↩

- Right?! Heretical! This camera is so beloved. And though I, too, was initially seduced, I found it didn’t hold up in the long run. The buttons felt flimsy, the rear screen cracked within the first week of owning it (a first for me and any device), the manual focus haptics were atrocious (diaphanous, with little feedback, almost unusable, especially compared to the Q), and though the images were nice and all and of that special Fuji je ne sais quoi, they didn’t knock my socks off. *ducks!* ↩

- This is the curse of the iPhone. Now that we’ve used iPhones, no touch screen matches our tactile expectations. Touch has to respond quickly. Unlike hardware buttons, capacitive touch offers no immediate affordances to let you know activation has occurred aside from something on the screen changing. And so if there is a lag between a tap and reaction, the user is made to constantly secondguess taps. Whereas lag with a hardware button isn’t such a big deal — you feel the nub depress, the latch click, some mechanism inside the machine activate and even if the on-screen response is delayed, the overall experience is one of solidity since the tactile feedback is instantaneous. ↩

- (Please just weatherproof the Q.) ↩