Tools and Creative Permission

On the feedback loops between our work and the objects around us

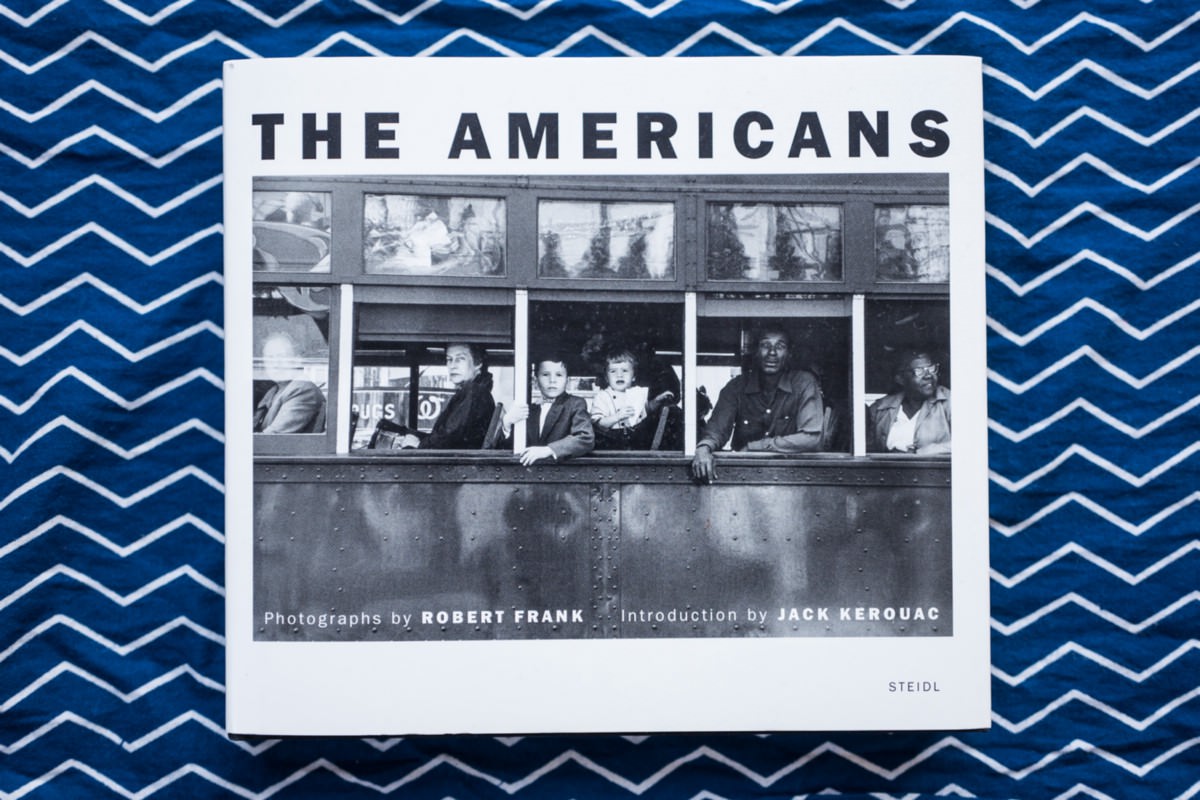

Originally published by: MediumWhen Robert Frank finally sat down to divine his seminal photography book, “The Americans,” he had to sift through more than 28,000 images.

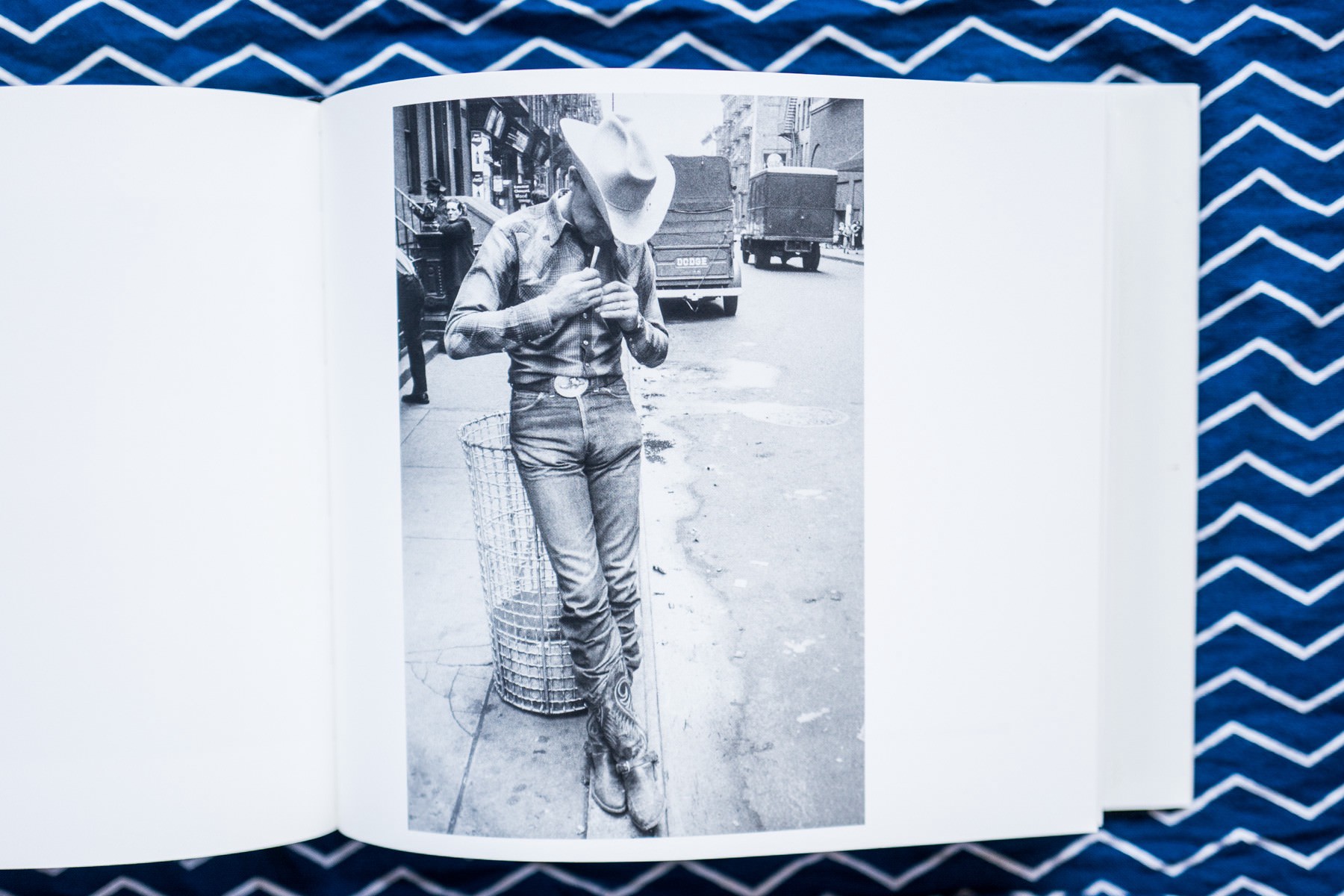

In Frank’s vast collection were snapshots of an America that had rarely before been caught on film: snaps of Manhattan cowboys sitting atop garbage cans, snaps of suspendered men in straw hats chatting in a courthouse square, snaps of teenagers making out on picnic cloths, snaps of a segregated trolley in New Orleans, snaps of a lone elevator-operator girl from within the elevator. Technically thematic between these snaps was the feeling that they were, indeed, snaps. Fewer slow compositions, more clandestine shots.

Frank produced those images over the course of a year and change, but this was in 1955 and 1956, the heady days of analog, back when taking a photo meant committing to a certain physicality, of affecting silver halide crystals with photons inside a box, and then developing and eventually printing those captures to see what was or wasn’t worthwhile. Today, individually we may capture hundreds of images in a single day—collectively billions, many ephemeral within apps like Snapchat—and see the results immediately, the cost of a shot having been whittled to essentially nothing. But back in 1956, 28,000 images over a year represented a few rolls of film a day and a lot of time in the dark room. It was a serious investment.

Frank managed to distill those 28,000 images into an astonishing 83, representative of an intimate gestalt of his cross-America trip as filtered through the eyes of an outsider. He was a Swiss citizen who had come to the United States to see what could be seen and thrust his discoveries upon the American people like a funhouse mirror to the face. So arresting were Frank’s images in the moment that Jack Kerouac wrote in the book’s introduction, “After seeing these pictures you end up finally not knowing any more whether a jukebox is sadder than a coffin.”

What’s most extraordinary about Frank’s images is how banal they now seem. He set a precedent, and we’ve been awash in copycats for the past 60 years. But when reflecting on Frank’s work, it’s easy to ignore the tool that enabled him to “snap,” to be discrete enough to take, for example, the photo of that elevator girl, the candid shot inside a bar in Gallup, New Mexico. He was using a Leica IIIf rangefinder, which had been released just a few years prior to his trip. At the time, it was one of the smallest and most capable 35mm cameras you could buy.

Kubrick and his Leica III

In a way, you could say the Leica (and more specifically, 35mm film) gave Frank the permission to go on that trip. Of course, he still could have traversed the states on his Guggenheim fellowship, taken a different set of images with a different kind of camera — but it’s unlikely he would have captured 28,000 images with a large-format camera. Those tools were simply too onerous to deploy, too conspicuous, and the cost per image too high. And so the parameters (a nearly silent shutter, inconspicuous size) and technology comprising the little Leica bestowed Frank with a strange permission to shoot abundantly, in new and sometimes weird ways, from the hip, brazenly, in a way no other camera would have. It made him a spy. To see ourselves as we were — like suddenly coming upon a mirror for the first time in middle age when you’ve hitherto seen yourself only in oil paintings, posed and composed — shocked us all.

I’ve come to think of tools as granters of permission. Things from which an artist can divine permission — the permission flowing either from the formal attributes of the tool to artist, or from the artist’s perception of the tool back into themselves. Either direction gets you to the same place. Many of us, to varying degrees, fetishize certain objects as having magical powers that enable, most often, creative processes.

The right kind of hand plane can inspire someone to build an entire table. The right antique sewing machine can be the prime catalyst begetting a new pair of jeans. Behold the cottage industry of notebooks: How many Moleskines or Field Notes notebooks have been the function that forced the hand of a writer or illustrator down some otherwise unexplored creative path? This is not to say that the right notebook or camera or sewing machine produces brilliance — of course not. But the right tool in the right hand might be the very thing that whispers to that artist. “Hey, what about this?” A dollop of permission.

Me and my GF1 just outside of Machhapuchhre base camp, November 2009.

The first time I experienced a distinct sense of the connection between tool and permission was back in 2009, hiking to Annapurna base camp in Nepal. I had taken with me Panasonic’s new GF1 model camera, a micro four-thirds camera, named for the size and aspect ratio of its sensor (4:3). A standard SLR or DSLR (digital single-lens reflex) camera has a pentaprism and mirror aligned in such a way that allows a photographer to compose shots through the lens. Remove this contraption, or go “mirrorless,” and you get a much smaller camera. The GF1 was such a tool. It worked much like a smartphone camera works today — you compose your image on a small LCD screen on the back, with no dedicated viewfinder (pretty innovative at the time!).

Climbing out of Pokara

As my Nepalese guide and I made our way up from the township of Pokhara toward Machhapuchhre and base camp beyond, I found that the people in the villages we passed through seemed far less intimidated by the GF1 than any other camera I had traveled with before. As a corollary, they seemed far less intimidated by my presence. I was no longer an avarice-laden white male having come from afar — lifetime fortunes spent on a box fitted with kilograms of bulging glass strapped to his face — to photograph the “others” and take their images home like trinkets. Instead, I was a goofy white male, smiling, with an actual face, holding a funny little box — relatively inexpensive — at chest height, with a pancake lens that projected no airs of seriousness, but rather a kind of impoverished curiosity.

Eye contact

In other words, I felt I was perhaps a commiserable human — in a way I hadn’t felt with other cameras — as the people I met led me into their homes, shared food, posed, laughed with me. I think they may have even felt pity for me. Clearly I was projecting, but it was astounding how a few small tweaks to the modality of a tool made all the difference with internal and external perception.

Basecamp at night

The overall experience of using the camera — a tiny, toylike contraption that captured professional-quality images — was so joyful that upon returning home, I immediately wrote up the experience in an essay, “The GF1 Field Test.” In the end, the tool was a two-part gifting of permissions. The first permission: to hike up to Annapurna base camp and document the journey (and have a blast doing it). The second: to share that experience with the world.

That GF1 Field Test was the first time I had wholly committed myself to an essay. I spent more than a month working on it, designing it, refining it. The moment I published it, a journalist friend asked me over beers why I published it on my website instead of selling it to a magazine. He didn’t understand the potential power of an Amazon affiliate link properly deployed. The piece did incredibly well: I sold thousands of GF1s. (I remember the strangeness of sitting down on an airplane soon after hitting publish and spotting a guy across the aisle holding a GF1. He recognized me, thumbs-upped the camera, and winked.) Those referral fees from Amazon? They paid my rent for years. Would just any tool have inspired this chain reaction? Probably not.

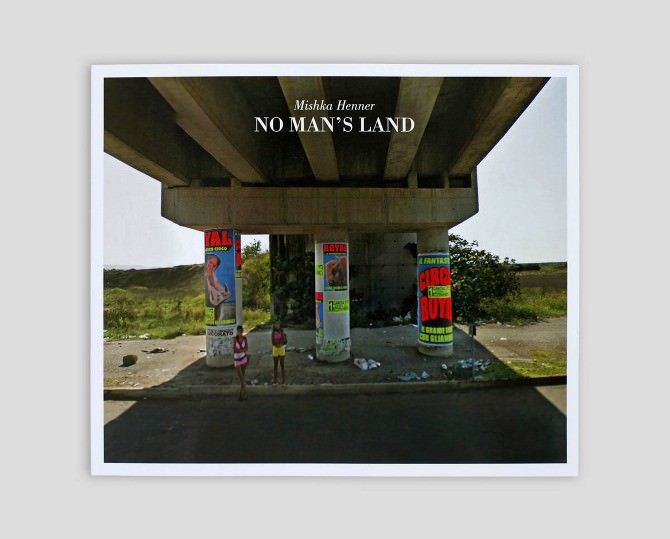

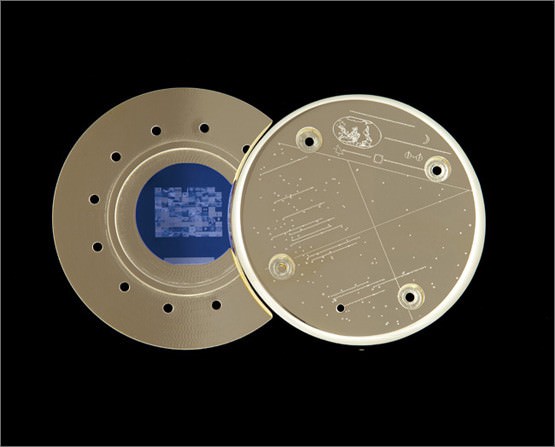

The images in artist Mishka Henner’s book “No Man’s Land” feel intentional, unwavering. The shots bring to mind a similarly deliberate stillness you’d find in a scene from an Ozu film. A camera plopped down on a tripod, the figures assembled just so, and then a shutter release.

But no shutter was ever consciously released to produce Henner’s images. They were culled from Google Street View — a thoughtless, emotionless, relentless sensor affixed to a car or helmet, a computer stuffed in the back seat or backpack, capturing as a human navigates a city or landscape, filling in data black holes on a map. A machine disregarding of form; pure information collection.

Google Streetview Car

Filtered through the eyes of an aesthete, this set of data can be sliced and reconstituted into something beautiful, even meaningful. And this is just what Henner and his ilk (Street View Portraits on Instagram, for example) have done and continue to do — the data cullers, photographers as hunter-gatherers of precaptured images.

Still from No Man's Land

According to Henner, “‘No Man’s Land’ represents isolated women occupying the margins of southern European environments, shot entirely with Google Street View.” I love the phrasing “shot entirely with Google Street View.” A smile-inducing headstand of a way of looking at things; choosing images from Street View is photography with the time element removed. (A universe frozen, the photographer picking angles and crops.)

Still from No Man's Land

Henner has built a career as photographic subversion artist on these found or refound images, leaning on large data sets. His collection “Fifty-One U.S. Military Outposts” contains images of “overt and covert military outposts used by the United States in fifty-one different countries across the world. Sites located and gathered from information available in the public domain, official U.S. military and veterans’ websites and forums, domestic and foreign news articles, and official and leaked government documents and reports.”

From 51 Military Outposts

From 51 Military Outposts

There is a latent permission in Google Earth—an incredible tool if there ever was one—the same flavor of permission granted by a Leica III or GF1. The same whisper in the ear: “Hey, what about this?”

These data sets comprise a staggering collection of private information about public places. Data from which we are unable to easily opt out — private citizen or, in the case of the military bases, the U.S. government. The collection of information being so vast that even if you opt out, it’s likely that some other collector, some other private set of public imagery, has taken up the slack, captured the very thing you don’t want captured.

We look into the courtyards of neighbors, otherwise hidden from sight behind walls. The emperor’s roof of the imperial palace resolves from Gaussian blur to individual tiles with each zoom tick. Through artists like Henner dedicating time to these troves, we begin to understand what they contain.

The Imperial Palace, Tokyo

Henner’s otherwise digital work also gained a kind of corporeal authority by leveraging print-on-demand (POD) book making. We tend to forget that the streamlining of physical book production is as much a product of the digital revolution as any iPad or Kindle. To be able to make a single copy of a full-color book, hundreds of pages long, and have it arrive in just a few days for less than a fortune is nothing short of a miracle. Even 20 years ago, this was a nearly impossible ask.

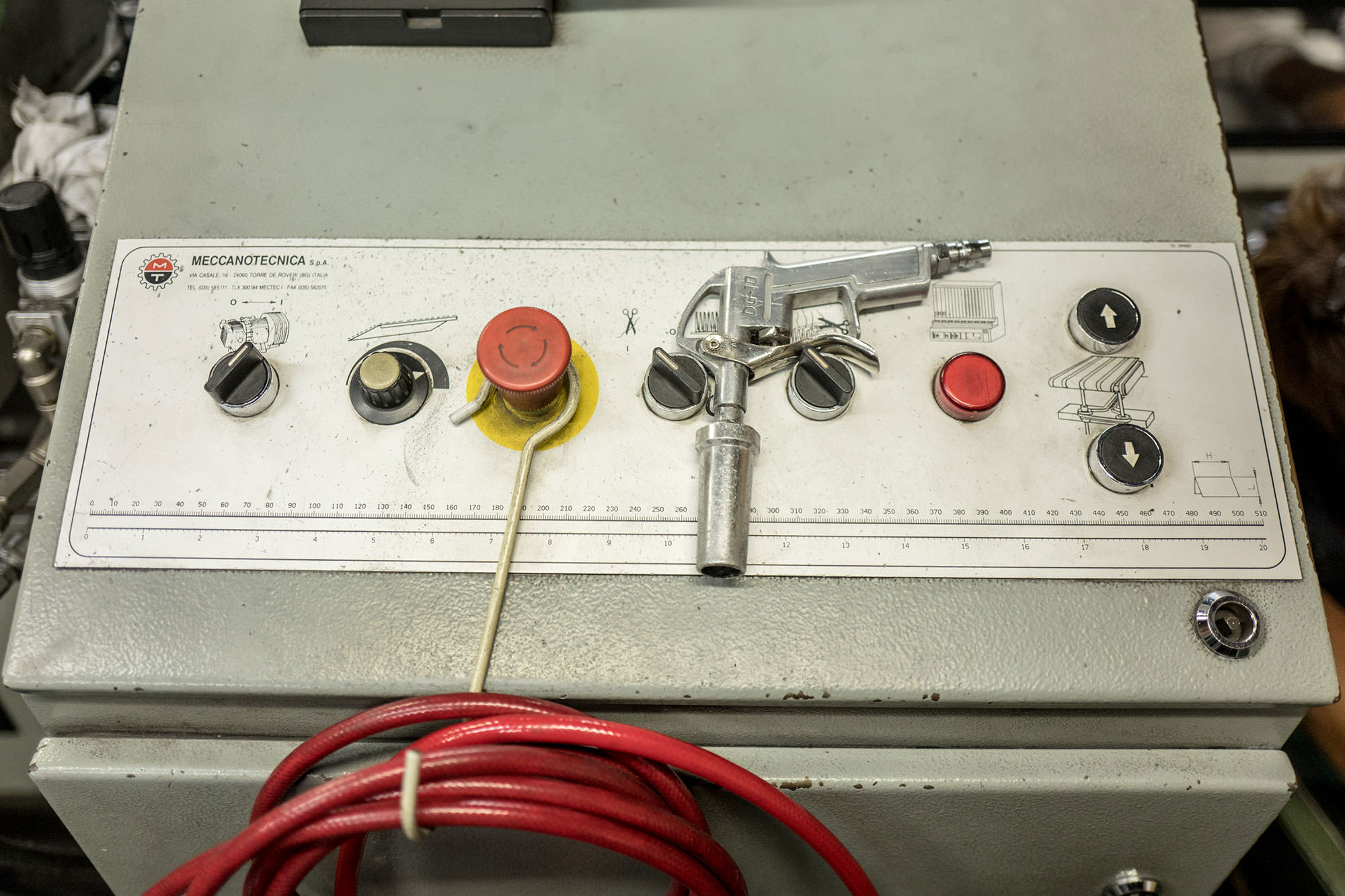

Espresso Print on Demand machine

POD uses digital printing to produce single copies of books as needed. Offset and letterpress printing methods produce higher-quality output, but because of the up-front costs in time and labor, they aren’t economically viable for one-off or small-run editions.

Although POD was available in the mid-1990s from companies like Trafford Publishing, it didn’t hit its stride until the mid-2000s. With mass-market-focused companies like Lulu (founded in 2002) and Blurb (founded in 2005), suddenly the permission to produce a single copy of a book, and at a reasonable price, was available to anyone with a computer and internet connection. Many of the first POD companies focused on text. Blurb distinguished itself by focusing on high-quality, full-color photographic reproductions that looked and felt great.

Over the past decade, the more our lives have become digital, the more we seem to act on some primal need to hold things in our hands. Although nearly every album in the world is available online, sales of physical records continue to grow. And although printed book sales slumped in the early 2010s, they’ve since rebounded — along with the health of indie bookstores.

I’ve lectured at the Yale Publishing Course for the past seven years, and questions from publishers around the world — big and small — shifted from “What do we do about digital books?” in 2011 to “Should we be making apps?” in 2013 to “Should we care about anything but Kindle?” in 2014 to “What kind of paper did you say you used in that book?” in 2016. The lack of worry about — or even interest in — digital books or about the future of traditional publishing has been illuminating and, in some ways, shocking.

And so Henner, who has produced print-on-demand versions of many of his projects, used the cost-effective book-making process as part of a one-two punch: a bitwise data set mixed in a digital crucible and poured into the container of a book. Suddenly these fleeting images made by a Googlemobile in the Italian countryside were tangible, burned into an artifact that could be held in the hand. Much like Frank’s collecting and editing of his tens of thousands of snaps, Henner holds up a mirror to our world under the constant watch of a lens.

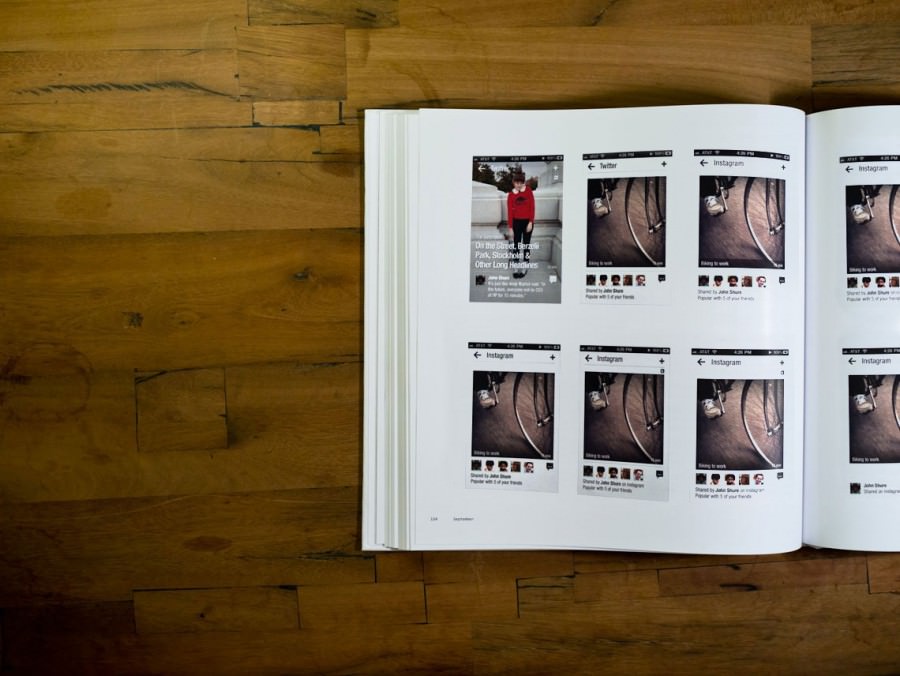

In 2011, I printed a book using an iPhone app. Permission from POD to make single-edition books had been growing, normalizing, and my sense of the extreme ephemerality of digital things was building to a mild crescendo.

The book was titled “Flipboard for iPhone.” I made only two copies.

Flipboard for iPhone, the book

At the time, the team at Flipboard — of which I was a member — had spent the previous ten months working on the highly anticipated Flipboard for iPhone product. Flipboard was a startup that had released an iPad app in the summer of 2010 to critical acclaim. It turned your social media streams into something akin to a magazine. It was perhaps the first aha moment for the iPad. As in: “Aha! Now I can see why this slab of glass and processors should exist!” Flipboard, when it was released, felt like promises of media’s future rendered real, and it was soon clear that the future of media demanded not just an iPad version, but also an iPhone version.

Making an app leaves little trace: Most of the production happens on the computer, hidden in folders. Like many computer-based activities, the months and long hours of making the iPhone edition of Flipboard had yielded little in the way of physicality, presence, or what you might call weight. A folder with one file is a folder with 10 files is a folder with a million files: weightless. At the end of 10 months, it was difficult to assess just precisely what it was we had done — how much design or engineering work had gone into the production of the app soon to be publicly released.

Flipboard for iPhone, the book, spread

I had made a dozen books as a publisher and designer over the decade leading up to working with Flipboard, but they had all been within relatively traditional channels — offset-printed books with 2,000-plus print runs, distributed nationally and internationally, months of work spent just on editing and design. And so at the end of the Flipboard for iPhone process, while sipping a mojito alone at a Cuban restaurant on California Avenue, feeling burnt out, I thought, “What if I spent a weekend, culled together all our digital work into a simple template, and printed it using POD?”

I collected every asset we produced in designing the app, and the company’s co-founder, Evan Doll, wrote me a script to suck out all of the commit messages left by engineers over the course of development. In the end, the book measured one by one feet and contained 300 pages, with 80 pages of commit messages in four-point font. If you look at those commit pages from afar, they seem like robot gibberish, but upon close inspection, they’re lush with an intimate and bizarre humanity: “Add shadow to bricks.” “Now we should be safe to call the back button Favorites.” “If we’re testing, go totally nuts and customize the modal account setup navigation bar tint color. Boom, headshot!”

Flipboard for iPhone, the book, spread

The app publicly launched. The book was printed. I presented it to the team at a post-launch meeting, and some of us started to tear up. It seemed that for the first time throughout a long process, we had a sense of what the hell we had made. It was an object that — like Henner’s books — would have never existed were it not for POD, for the strange permission granted by the confluence of technologies enabling fast, cheap, digital printing.

As time has passed, the book has become even more important to me. The Faustian bargain you enter into in developing for Apple’s App Store is that Apple will handle sales and distribution, but you can never go backward — you can never install or touch an old version of an application. And so that version of the app we released in December 2011 — an app composed of tens of thousands of person hours — exists and can be viewed in only two places: “Flipboard for iPhone” in the company offices in Palo Alto and “Flipboard for iPhone” on my shelf in my studio.

Flipboard for iPhone, the book, cover

Art stands on the shoulders of engineers and geeks. Contemporary art, especially (but so too, for example, the Sistine Chapel, the mathematics of its arches, the alchemy of cobalt oxide and copper-bearing minerals comprising its stained glass). Photography, video, and computer-generated art are all beholden to some degree to curious scientists working within the the machinations of capitalism or academia. (This is why, for example, if you look at computer art in the 1960s, 1970s, or even early 2000s, the people creating it were often the scientists or programmers who designed the platforms.)

Light L16, a 16-lens camera

What represents the forefront of photographic technology in 2017? It might be a 16-lens camera announced in 2015 called the Light L16. It begins shipping in the summer of 2017. It has 16 lenses. Sixteen lenses? I know, it sounds ridiculous. Why would you need 16 lenses? Here’s the thing, though: Most everything innovative in technology seems like an extravagance at the beginning.

The oldest surviving photograph is monochromatic, blurry, geometric, taken in 1826 or 1827. The atavistic image is of the Le Gras estate in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, France. The exposure took several days to complete.

‘View from the Window at Le Gras,’ Nicéphore Niépce.

It would be almost a hundred years before the now-common 35mm format was popularized by Oscar Barnack of Leitz Camera (“LeiCa”). The 35mm format proved to be so popular and standardizing that even when we talk about full-frame sensors in our digital cameras, we’re talking about sensor size relative to a single full frame of 35mm film.

Compared to large-format photography, handheld or 35mm photography was seen as a gimmick, the resolution minuscule, details lacking. Being of no use for “serious” photography, it was relegated to family photo albums and miscellaneous snapshots. It’s easy to construct a straw man: Who needs to be able to take so many low-resolution photographs in rapid succession? (Well, responds our straw woman, how about someone making a movie?) But it was precisely from this gimmick that Robert Frank eventually divined his permission, that we learned to look anew at the United States. And it was those same shrinking impulses of efficiency that spawned our current crop of smartphone sensors (the research into and production of beginning as far back as 1968) and lenses, all the way into the 360-degree camera atop a Google Street View car. And — taking it further — our desire then to print these many images, combined with desktop publishing software and improved printing technologies, provided the business plan for a company like Blurb to acquire the capital to start printing books on demand.

There is a strong thread between the invention and standardization of smaller, more accessible film types a hundred years ago and a one-off printed book of satellite images. Which is to say — the trickle-up (assuming time moves forward or up) effects of technological advances are mostly impossible to predict. As Steve Jobs said in his widely circulated commencement speech, “You can’t connect the dots going forward. You can only connect them going backwards.”

Light founder Rajiv Laroia has an incredible 45-minute technical talk about his company and the nature of its 16-lens camera. It’s well worth your time if you’re curious about how creative technologies evolve. Laroia goes into fascinating detail about how the camera works and the unique benefits of this device — conferring upon photographers even more creative control than any standard single-lens camera possibly could.

The L16 leverages the economies of scale resulting from Apple and Samsung market competition their one-upsmanship drive to produce better smartphone cameras and the insatiable appetite around the globe for smartphone ownership. In the case of the L16, the company’s engineers-as-artists were given permission to see what they could produce if lenses were effectively free ($1 each) and accompanying sensors a rounding error ($3 each). From no phones in cameras a decade ago to being able to put 16 cameras into a device the size of a phone for $70 today.

These many cameras have clear purposes. First, they allow tremendously high-resolution images to be captured in the small device through smartly overlaying exposures using computer-vision algorithms. The result is a 52-megapixel image — higher than that of most full-frame professional DSLR cameras. But perhaps even more exciting is that the various angles captured by these offset lenses provide depth information for in-scene objects. This allows post-facto bokeh rendering at any point in the image — effectively giving the photographer full creative control after the image was captured.

This video summarizes it well:

Had Google Street View used this device to capture images, Henner would be able to choose the angle and the crop of the image as well as the depth of field, the focal point. Technology atop technology granting unexpected permissions.

As technology normalizes the production of an abundance of images and books, the value of our work increasingly becomes connected to curation or selection.

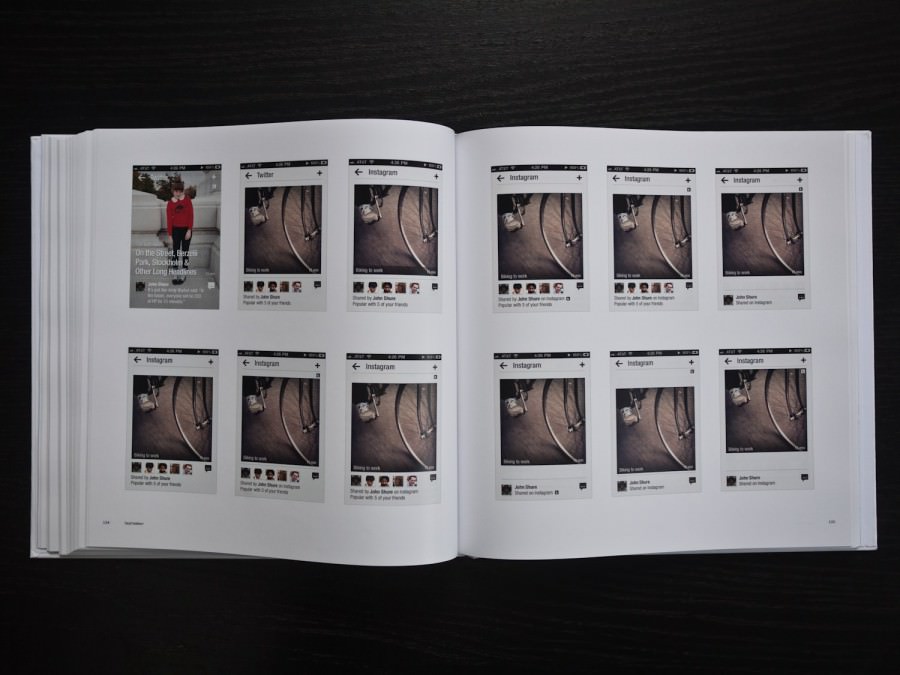

Trevor Paglan’s ‘The Last Pictures.’

In 2012, artist Trevor Paglan micro-etched 30 photographs onto a disc “encased in a gold-plated shell, designed to withstand the rigors of space and to last for billions of years.” The project is called “The Last Pictures.” The disc is on a satellite locked into an endless geosynchronous orbit, with the hope of it remaining after we inevitably destroy our world.

The Voyager Interstellar Record.

But Paglan’s work of taking permission from space technologies to shoot photographs into the cosmos is nothing new. The most famous disc in space is the Voyager Interstellar Record, produced in 1977 by Ann Druyan and astrophysicist Carl Sagan. The record contains “a selection of Earth’s greatest music, a photo gallery of our planet and its inhabitants, and an audio essay of terrestrial sounds, both natural and technological.” While Trevor Paglan microetched onto a substrate, no such technology existed in 1977. And so, looking around at what they had, radio astronomer Frank Drake decided on a phonograph record:

Extraterrestrials would stand a good chance of figuring out how to play back such an old-school technology — and phonograph records were tough. By one estimate, the etchings on a suitably-shielded metallic phonograph record could last for hundreds of millions of years in interstellar space, eroded mainly by a slow drizzle of micrometeoroid impacts. A copper record coated in gold would satisfy the thermal and magnetic requirements of the Voyager probes.

Katie Paterson’s ‘Earth Moon Earth’ before and after transmission.

The Scottish artist Katie Paterson’s “Earth Moon Earth” piece transposed Bach’s “Moonlight” Sonata into a series of Morse codes. Those codes were then reflected off the moon in a radio transmission and recaptured. The resulting moon-bounced data was imperfect, the Morse code slightly garbled. This garbled code was then retransposed into music and played on a player piano. The “Moonlight” Sonata was now, truly, composed of light from the moon.

The final image in Frank’s The Americans is a head-on shot of the passenger half of a car filling 80 percent of the frame. A single visible headlight is lit. Its curves are those of cars from the 1950s, rounded and smooth. In the car sits a woman — in the front or back seat, it’s unclear. The image is somewhat out of focus, the resolution and grain of the film making most everything vibrate with fuzziness. A boy’s head rests on her shoulder. He is presumably her son. The car is stopped on a dirt road in what appears to be the desert (the caption reads: “US 90, en route to Del Rio, Texas”). Why is Frank standing in front of this car? Why doesn’t the woman with the tired expression acknowledge the camera, Frank standing before her? We don’t know; we can’t know. All we have is this image, a miracle in and of itself of some instant in time filtered through hundreds of years of technology and through the eyes of Frank, who chose, among many moments, this very one to pull forward to today.

Henner culls Google Maps to expose the edges of data collection. Patterson beams songs into space, creating a poem and dialogue with long-dead composers. Print on demand allows us to print out our iPhone apps to understand what they’re made of. A well-made tool in the right hand, a dollop of permission.

“Hey, how about this?”