Episode 7

Bookends and Beginnings — Chicago — Dan Sinker

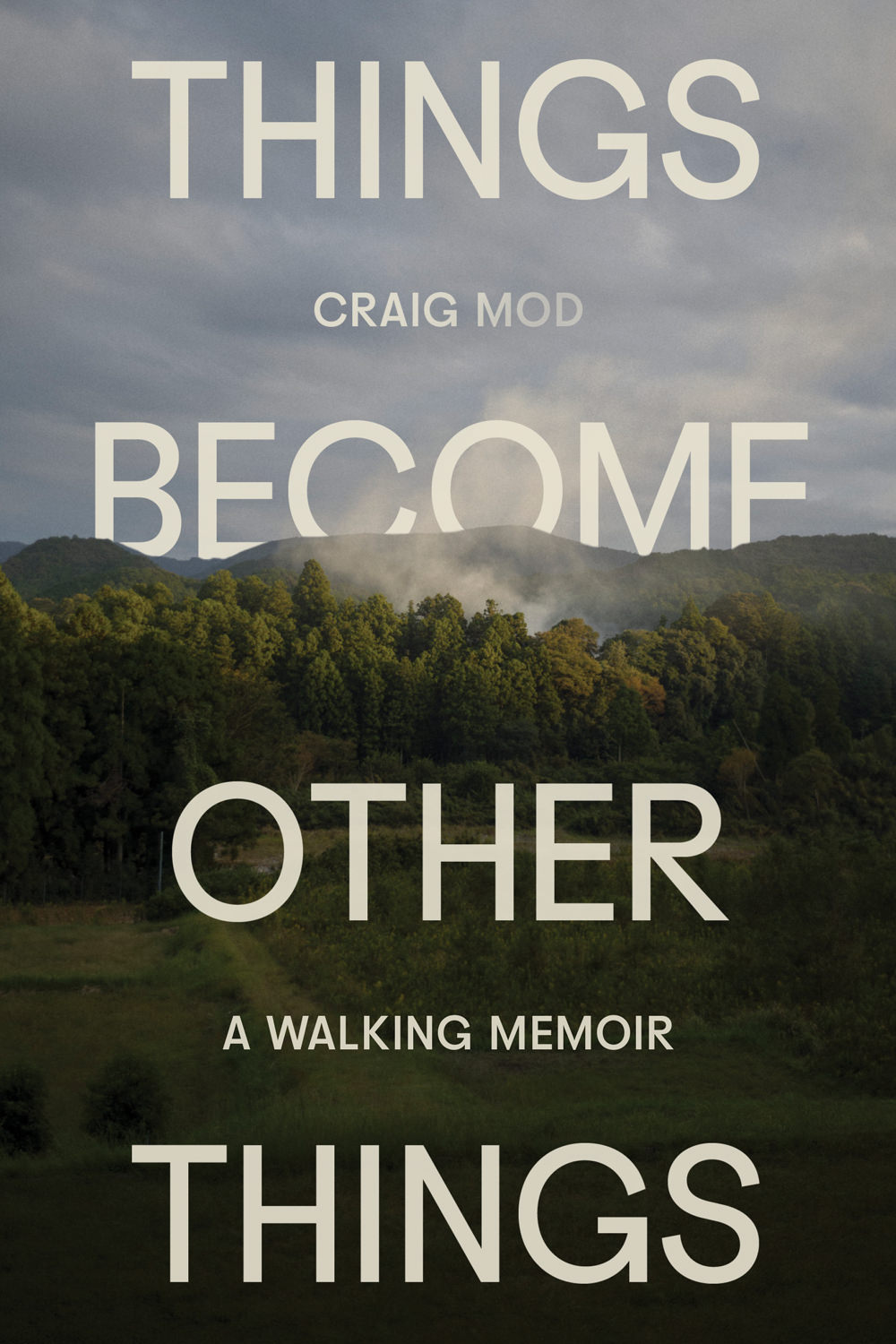

Craig Mod in conversation with Dan Sinker at Bookends and Beginnings in Chicago, chatting for fifty-nine minutes on May 19, 2025

Dan Sinker — stalwart Chicago writer, podcaster, and surrealist Twitter account maestro of @MayorEmanuel — and Craig discuss his experiences and insights on walking, storytelling, and embracing offline moments. He shares anecdotes from his walking journeys in Japan, reflecting on the impact of technology on daily life and the value of creating intentional disconnections. Mod highlights the inspiration behind his latest book, including the deeply personal process of honoring a childhood friend and the various encounters that enrich his solitary walks. Additionally, he touches on the unique community built through his membership program, the balance of utilizing technology for creativity while protecting mental well-being, and the significance of understanding and cherishing human connections through both his travels and personal life experiences.

Guest Links

Chapters

- 00:00 — Introduction and Welcome

- 01:01 — The Offline Experience of Walking

- 02:06 — Walking Rules and Boredom

- 02:49 — Cultural Observations from Japan

- 04:29 — The Impact of COVID on Walking

- 05:38 — Daily Walking Routine and Reflections

- 07:37 — Balancing Solitude and Social Interaction

- 09:31 — Writing and Transcribing During Walks

- 10:32 — Extended Walks and Their Benefits

- 16:41 — Themes of Grief and Death

- 19:45 — Cultural Differences and Social Commentary

- 28:48 — Building a Membership Program

- 31:43 — The Power of Tangible Rewards

- 32:04 — Retaining Creative Control

- 33:32 — The Importance of Membership Programs

- 33:56 — Connecting with People Through Travel

- 34:53 — Writing About Japan: A Delicate Balance

- 40:38 — Tech: From Empowerment to Hindrance

- 52:13 — The Adoptee Experience

- 59:34 — Concluding Thoughts and Audience Q&A

Subscribe to the Podcast

Transcript

Bookstore: Thank you both for being here and thank you all for coming.

Dan Sinker: Thank you. Thank you.

It’s so great to be here and it’s great to have you here, Craig, I live here in Evanston and I just wanna give a quick shout out to bookends and how they are killing the game at book events. It’s awesome to see because most of the time when authors come through. Chicago, they’re in Naperville and that’s really far away.

So it’s nice. It’s nice to have authors here and it’s nice to have you here, Craig, and to get here, I walked nice because that felt thematically appropriate. And also because we only have one car and my wife was gone and I was. Texting with you and I was texting with my wife who was coordinating with our son and I realized I was doing it all wrong, right?

Like I was walking wrong. I was like looking down and on my phone the whole time. And this book is so interesting ‘cause it is, it’s such an offline. And walking is such a kind of offline way of being and you’re telling this story and this book came out at a time where tech is has, which has already dominated our lives for so long, is trying new and fun, inventive ways of wind, its way even further into our lives.

I’m curious about what made you decide that kind of now was the time to tell this story in this way?

Craig Mod: Mainly Random House gave me a contract. That was the big, but first of all, thank you all for coming out. This is cool to see everyone. I don’t know where I am. I don’t know what day it is. I just put coordinates into a thing and go to places.

This is so cool to see and thank you Dan, for making the time and helping us figure out where to do this. That was helping us brainstorm places to go to and places to do these events. In terms of why now, it was really just. I think what, there was no real planning, but I think my, there’s probably also no coincidence that my, my interest in walking and my kind of commitment to it and then also doing it with my rules.

‘cause I have these walking rules. So when I’m doing walks, I have a few things. One is no social media, no news. I’m not allowed to read news sites. Basically not allowed to do anything fun online. So it’s all blocked. And then also no podcasts, no music. So you’re really trying to get to this place of, I, I say boredom.

People go why do you say boredom? But really I think one thing we’ve lost the, in the last few years, especially the last couple of years, is any sense of boredom. You have half a millisecond of downtime and you just reflexively reaching for the phone. And one of the things I’ve been noticing on.

US tour, I’m having all sorts of like double reverse culture shock and freaking, just freaking out seeing the state of contemporary America in a lot of ways. And one thing in Japan that I’m always mesmerized by is how service workers, and especially at the end of a movie, so a movie ends in Tokyo, right?

You go to see a movie at the movie theater, a couple things happen. One, the lights do not come on. When the movie’s done, the credits start rolling and you just sit there and everyone just sits there. Every, no one gets up and no one looks at their phone. Everyone just stares at the movie screen and watches the credits and they probably can’t even read ’em.

‘cause a lot of times they’re in English or whatever and they just, it’s like this moment of kind of reverence or whatever, respect for the thing. And then when it’s done, everyone gets up and so I, and I keep watching, this is like my little like barometer of is Japan doomed or not? Is if I go to the movies and if I see people getting up at the end of it, or.

Picking up their phones, not being able to, hold back from the dopamine hit that’s waiting for them in the pocket. So anyway, but traveling America and just seeing how everyone, everywhere, any millisecond of downtime, they have people in hotels, people in shops or whatever, like everyone’s got the phone, they’re just noses in the phone all the time.

Like to a degree that you don’t see in Japan. You see it differently in Japan, but you don’t see it in this way. And so anyway, that’s, I think you just feel this, right? This is, everyone kind of feels this pervasively. And so for the last six or seven years I’ve started doing more and more of these intense walks with all these rules.

And what does it mean to really be bored? And what does your mind do when you’re bored and how you have to create artificial boredom. And and so that it was exactly four days or four years ago to this day that I was doing the walk that became this book. And that was a walk during peak COVID. We didn’t know what was happening in Japan.

The borders had been closed by this point for about a year. We didn’t know when they were gonna open. The cases were really low. It was like 12 cases in all of Japan, and yet everyone was being super careful. And the area that I was walking in, mi and Wakayama pre fixtures. It was like three cases or four cases.

And yet everyone was like, really I’m doing this walk, no one is out, no one’s staying in the hotels. I have the road to myself, the hotels, to myself. And so it was this weird, I think, reflective moment for me. Extra reflective because of the silence, because of how you couldn’t go anywhere in the world.

Like I couldn’t leave Japan ‘cause they wouldn’t let me back in. So I was stuck, but it all felt really good. Like it’s actually for me, a relief. When everything shut down. In a strange way, I was lucky. I was able to keep working and actually I was able to start doing all the work that’s kinda led to what I’m doing today.

That the downtime, the closing of everything kind of catalyzed that. But I also just realized I’d been moving too quickly. My life was just too full of stuff. And anyway, this walk was one of the walks I was doing during that period, and it was just a silence to it all that was, that felt special.

And I think that’s why this walk has turned into this book. As, and I have. Several other walks that have not turned into books to this degree, although they’re on the docket to potentially turn into books. But I think it was that combination of the silence of COVID the world, slowing down a couple notches.

And then also I’ve been building up for a decade, this muscle to go offline. So it wasn’t a big ask internally for me to say, okay, turn this stuff off and just be present, and just photograph people every day and talk to the people on the road that I did meet the farmers that were working their fields and stuff like that.

And then at the end of the day, spend four or five hours collating. So I’d do 20, 30, 40 kilometers of walking. And one of my other rules was take a portrait of someone before 10:00 AM and so it’d be like nine 50 and I’d be like, oh shit. I have to taken a photo of someone and I’d just, whoever’s nearby, Hey Farmer in the field.

Hey, can I take your picture? And everyone was, even though it was COVID times, everyone was pretty. Relaxed about that stuff. And so I’d go into, that’s a Tommy Matt shop. And it was the sort of thing that I think when you’re habitually or pathologically online, you forget about these sort of interactions and delights that are just waiting for you every day, all throughout the day of amazing people you could be connecting with.

And the point of the portrait by 10:00 AM is to have one. Exciting, meaningful connection to catalyze all the other creativity for the rest of the day. And it really does, it infuses me personally. I get high off of having a connection with a stranger and having a mutually kind of positive interaction.

They’re excited. I’m excited. And you have a little piece of art or culture or whatever that comes out of it. It’s very cool.

Dan Sinker: Yeah, you bring up a, an interesting point. This is also a very funny it’s like we’re having a conversation on the bus. We’re both facing forward, turning toward each other.

The book has this kind of solitary ness to it, right? And the practice of the walk has a solitariness to it, and yet it’s also really alive with. With all of the people that you meet along the way. And I’m curious about and I think you’ve hinted at it at least with this, with the portrait thing, but how you shift gears from deep in your head or deep in silence to suddenly coming upon someone and engaging with them.

Like how do you shift that gear? How do you begin that process?

Craig Mod: Yeah. The thing is like even if I talk to 10 people every day. There’s still eight hours and 20 minutes of talking to nobody. So it’s like mostly, it’s mostly blank space. And then the another one of my rules is I just have to say hello to everyone enthusiastically.

So it’s just about having these stupid rules that, when I’m back home, if I’m in Tokyo or Kakuta or whatever, you just don’t do these things because I don’t know, why don’t we do these things? I guess it’s overwhelming if I, if you said hello to everyone in the city. That’s that’s exhausting.

And so when you’re out on the road, you can create these alternative personalities. And what I found is just by doing that perfor, the performance of being someone else or being a better version of the self, which I find therapy is essentially that. It’s every week I’m just, for an hour, I’m gonna try to be the best version of myself, the most honest version of myself, with myself.

And then it turns out that if you keep doing that week after week, it starts to bleed into the rest of your life. And so the walks a big part of it is just creating this archetype of what the fullness of a single day could feel like. And whether or not you’re able to bring that back a hundred percent to your day to day is secondary to the fact that you’ve experienced it.

At the end of the day, on, on these walks, I get in bed and it’s just total exhaustion ‘cause it’s, 20, 30, 40 k photographing people, hearing stories. And then when I’m not talking to people, a big part of it is transcribing. Like my mind just immediately goes to writing. To pros. So it’s just writing writing.

When you take away all the other distractions, just writing writing. So I’m transcribing stuff into my AirPods or whatever. And then I get to the end and it’s five o’clock, six o’clock, and I’ll spend the next four or five hours taking those transcriptions, using those as jumping points for essays, for pop-up newsletters, things like that.

And so then you do have this, so during the day you’re using your body, you’re whittling your body all the way down to nothing, and then you have four or five hours at night where you’re, for me to do a photo edit, rev. Processing of photos plus several hours of writing, writing two, three, 4,000 words, that really rings my brain down to nothing.

So when I get in bed at night, it just feels like I’ve had the most full day possible. It’s just, it’s incredible. And you do that. The really critical thing is doing it day after day after day. As opposed to doing it just like one or two days in a row. I’ve walked Tokio a few three times or todo twice.

Nendo once I’ve walked the Keep and Insula Bunch and you’ll meet other people that are doing these walks. So these are the Tokio and Nendo are walks between Tokyo and Kyoto and it takes, if you take your time and you’re not crazy about it, it’s about four weeks to do the whole walk. But you’ll see old kind of retired couples and they’re doing it weekend by weekend.

So they’ll come off for the weekend and do these two days and then they go home and then they come back and they do the next two days. And that’s great. But in the same way that like Vipasana doing silent meditation, you need the 10 days because it takes three days for you to arrive at the retreat mentally, and then you have a couple of days of acclimation.

And then finally on day 5, 6, 7. You get the benefit, you start to experience truly like why you’re at this retreat, why you’re doing the 10 hours of meditation a day. And then day eight comes and you start thinking about, oh, I’m gonna leave in a day or two, and then day nine come nine comes. And all you can think about is the next day when you’re gonna be released and you’ve made it.

Oh my God, I’ve made it. And so you’re not there anymore. And so the same thing with these walks. And you can do ’em weekend by weekend, but you’re missing out for me on what the real potency is, which is the repetition and the repetition over weeks. And that’s where the, to me, the main value comes from.

Dan Sinker: So I wanna touch on something you just mentioned, because I feel like my mental model of this whole book just changed, which is my mental model of the book. You are walking quietly and contemplatively for hours on end, but you are actually talking out loud to yourself. Oh, yeah. And recording. So you’re the dude walking through the forest.

I, in the shadow of COVID where no one else is around. Yes. And somebody’s, half a kilometer ahead of you and they’re like, what the fuck is coming? Yeah,

Craig Mod: okay, got it. Yeah, no, it’s very active. The offline is, I am offline in the sense that I am actively choosing not to go online.

Yeah. But I’m very, someone asked me the other day, they’re like isn’t there some sort of competition between wanting to transcribe things but also being hyper present? Being really, just being really in the moment. And for me, the transcription, the thinking, the photographing, the talk, that all makes me more in the moment actually because it makes me more observant and it makes me more sensitive to these really beautiful, weird things someone might say, it’s like there’s a passage in the book about, it staying with these, this old couple, hold on, let me find it.

It’s page 60, I think.

Yeah. So this old couple, it’s they ask me if I want a Western or Japanese breakfast. Most inns don’t offer a choice. Most are Japanese style only. So when I get the chance, I go western if only to shake things up. Big mistake. She bakes me five loaves of bread. Can’t believe I don’t eat them all.

The husband keeps gesturing for me to rip them apart and shove ’em down. My gullet, they stand and watches I carbo load. They’re unusually touchy. Squeeze my arms, check my body mass index. I use a translucent garbage bag to wrap up most of the bread. I tie it to my pack like a hobo. And while that’s happening, I’m just so hyper aware of it because I’m like, I gotta write this down.

This is really funny. This is really weird. So I find having a purpose at the end of the day of writing the essays, sending the popup newsletters, and then ultimately maybe having it be, become a book. It’s my attention across the wetstone I just feel so much more, I don’t know, willing to actively be present.

Yeah. As opposed to be passively present and. To me, that’s what, where the kind of all the fun and value of the walks lies. And it, I I sometimes in writing I’ll say, this is like an aesthetic practice, but it really does feel like that. Yeah. Like it’s not meant to be, oh, let’s go on a comfortable walk and have a good time and like just, take it easy.

It’s meant to be, let’s go and really look at the world. Let’s really be present. Let’s really, observe and try to capture it because you also forget so quickly. That’s one of the things you learn if you do design field work, research or whatever. It’s like when you’re in the field and you’re observing people and you’re doing things, you have to write that down immediately.

If you wait two days, you’ve forgotten half of it. So that’s where that rhythm of, at night, I get to the end and it’s just let’s get to work. That’s when the work starts and people sometimes go what if you meet someone cool and like you want to hang out, and it’s I live in Japan.

I’ll just call ’em after, like after the walk I’ll be like, Hey, can I come back over and then we can hang out. Then

Dan Sinker: that passage that you just read, that’s actually one of my favorite parts in the book. You end up having a con, this young woman comes in and you’re introduced to her as their daughter.

Yeah. And you crack wise with her about how much bread they’re making you eat and that kind of thing. And then later she leaves. And the elderly man says, she’s not my daughter.

She’s somebody that came and. Never really left, and they adopted her and, for lack of a better term.

And then, and that’s actually where the title of the book comes from. It ends with things become other things. And it’s a really beautiful passage because it, there’s a melancholy to it, right? And a sweetness to it that I feel like is actually very. Evocative through the whole book right.

In, in, in my many notes that I’ve written as I’ve read, I was like, this is a sad book about walking. And it is, there’s a sadness to it. Yeah. There’s, there is a level of grief in the book and it’s interesting ‘cause to me it’s written in the. In 2021. When, while at that point in America, we were like, doing beer bongs together and stuff, but like in Japan, they were still taking it seriously.

Yeah.

Craig Mod: And we still hadn’t, we didn’t have the vaccine still.

Dan Sinker: Yeah, which was just in, in terms

Craig Mod: of timeline through it. Think about that.

Dan Sinker: But death is also a main character in the book, in that the book is very much a conversation that you’re having with Brian, which is a childhood friend of yours who was murdered.

Bookstore: Yeah.

Dan Sinker: And I feel like this is again, coming into this theme of tech and analog, but the life we lead right now is so much about the denial of grief. And the denial of the idea that there is death here. And yet there’s so much of that within the book, whether it’s the direct address to your childhood friend or, walking in these ancient cemeteries and all of that.

And I’m just curious about how you managed to balance all of that.

Craig Mod: Yeah. I think Japan is very at peace with grief. That’s a big part of it. Living in Japan, you there’s kinda almost like a fatalistic sense of, obviously there’s all the WAA stuff and oh, things are gonna disappear and cherry blossoms are beautiful and death and let’s kill ourselves under the cherry tree and all this stuff.

And so there’s all of that kind of, that you’re constantly butting up against. But, just in general when you’re, when you live in a place that’s so geographically tenuous. With the, with the earthquakes and everything, the tsunamis, you just, you’re just at peace with it.

The fact that, at any moment a big, terrible thing could come and literally wash away the village. And so I think maybe that’s partially influenced maybe the tone of the book a little bit. But then also obviously during COVID and the quietude of it, but then also the peninsula itself is so silent and it’s depopulating.

And it itself is disappearing. That’s the real trigger that I started thinking. Okay. Started thinking about Brian again is, I’m walking through a place that’s socioeconomically post-industrial, so it’s logging and fishing and and other kind of there’s some mining and stuff that was happening on the peninsula and that’s all gone.

And yet there’s a kind of grace to their winding down of all that post-industrial sort of sense of things. And there isn’t the violence. There isn’t the drugs. And so the place I grew up in, which interestingly Ocean v’s. New book takes place in my hometown. So East Gladness is where I grew up, even though it’s not called East Gladness.

He, it’s just very, it’s barely, I don’t know why he doesn’t just say he’s writing memoirs. It’s very bizarre. But he essentially it’s effectively a memoir, a little case study of the town. And so you can see I think that book takes place in 2009. I’m reflecting back on basically 19, mid eighties to early nineties.

But you, it’s impossible for me to walk the peninsula, see that kind of socioeconomic parallel, and yet not feel any of the violence or the systemic failures that Brian and I grew up with. And that’s really what started triggering things. Was seeing the kids on the peninsula and thinking what would Brian and I have been doing?

Had we grown up here? How would we have turned out? How would this have worked? And that’s what catalyzed a lot of it. And then, I’ve done other walks in Japan that are, these are all linear walks. And I started to want to play around what if I picked 10 cities that were mid-sized cities that no one’s ever been to?

And what if I walked 50 kilometers in each of those cities? What would that feel like? And that actually turned into this really interesting, uplifting thing. There’s. Like a inversion of the peninsula. So the New York Times has a thing 52 places every year. They recommend 52 places you should go to.

And during that 10 city walk, I’d walk from cities in Hokkaido all the way down to Kagoshima on the bottom of Kishu. And one of the cities I went to was Mor moca. And New York Times that year was like, Hey, do you have a cool, anywhere in the world you want, anywhere in the world? It was not Japan.

They weren’t like, Hey Japan guy, tell us something cool in Japan. And I was like, Mor, this is such a great little city. And not that 300,000, that’s what you know, so it’s, decently sized. But it just had such good energy and it was because I’d been walking these peninsulas in these kind of post-industrial areas that I was actually so inspired and moved by the energy of these cities that the really beautiful active ones I found.

And I was like, amazing coffee shops, just lots of life. Young people starting businesses just had this vitality. That was undeniable. And yet no one in 23 years had ever recommended the city to me.

Bookstore: And I

Craig Mod: was just, this is bananas. So I did this really impassioned pitch to the New York Times and they don’t tell you if they’re gonna accept it and they don’t tell you where it’s gonna be on the list when it comes out.

And so then the list comes out. And that year number one was London for all the coronation stuff. And then number two was Mor oca. And so people freaked out. They’re like, why? Why? I don’t know. I guess it would be like picking Evanston or something like it have it be London number is the number one place in the world to go to.

Number two is Evanston. You’d just be like, what? We like Evanston, but why number two in the world? And then the Japanese media found out I spoke Japanese and that created this insane. Tidal wave of media reaching out to me and me being on TV and all this, and they said, oh, the mayor wants to meet you.

Come up and say, okay, I’ll go up and meet the mayor. And I go up to meet the mayor and thank God I put on a suit. I wasn’t really thinking about it. It was like first time I wore a suit in 10 years. I put on this suit and they’re like, I thought I was just gonna go shake the guy’s. And they opened the doors.

It’s oh, the mayor isn’t here. They opened the doors and behind the doors it looked like this, except you were all journalists and you all had giant network TV cameras on. It was bonnet. They totally bamboozled me and the mayor’s sitting on a little throne in the back. And I go over and I say hello to him and he says, oh, thank you Mosan, for doing this.

Good luck. And then he just left. And I hadn’t prepared, I hadn’t prepared a speech, I hadn’t prepared anything. And the first question, the guy, the journalists start lining up and they go, oh, Mosan, how do we solve poverty? And I was like, ah, you guys got the wrong guy. This is not, this is way above my pay grade.

I do not know how to solve poverty. I just think you have great coffee. And it was very weird that no one had told me to go have coffee at your, in your town before. And so anyway, that led to many more interviews. I’ve done like a hundred newspaper and TV things and magazines and all this stuff, but was what’s been great about it.

Is an apropos of this book and all this stuff is, everyone on TV wants to know what’s your favorite soba, what’s your favorite coffee? What, how many bowls of this did you eat? Da yada. They always wanna just talk about dumb food stuff. And and I’m like, they’re like, what’s your favorite soba?

I’m like, my favorite soba is national health insurance. I love national. It’s so delicious. That’s, but I, it’s turned into this conversation because no normal Japanese person would ever think about. The infrastructure that they’ve built socially, that enables a city like Mor Yoka to be so cool to allow all of these individuals to open businesses to not sacrifice anything to not.

Feel oh, I can’t afford healthcare, or I can’t do, I can’t have a family if I do this. I gotta have this job over here at this company, yada. So making none of these compromises. So you get this beautiful patchwork of funkiness, someone running a Japanese jazz bar or this kind of weird cafe that’s focused on this specific thing.

And so just making, talking about why that’s good and making, trying to make Japan kind of that stuff has been an amazing sub conversation to come out of having done walks like this. Where I see even in the worst bits, there’s still a grace that people are living by. And that’s really inspiring.

And it’s been fun to become a weird national I have a monthly radio show and stuff and I’m always like, I’m always like, healthcare is awesome. Who is Malta son? Why does he like healthcare? I’m like,

Dan Sinker: oh, that’s a good gear shift to the fact that you’ve been in the US for six weeks.

Yeah. Now. Four, four weeks. Four weeks so far. Yeah. Six week tour. Yeah. Four weeks. So a month. And it’s this month and it’s this United States and it’s 2025. And I’m curious about how being back at this moment in time with everything falling apart has hit you.

Craig Mod: Yeah, it’s weird. ‘Cause I’ve been, Japan’s have been my home for 25 years.

And there was this period, when Obama got elected it was kinda like, oh, maybe I moved back to America. This is cool, and then I did move back a little bit. I was living in Palo Alto, which was a really important period in my life, living with some really amazing people. And just, I think I talked about this on the Tim Ferriss podcast, but just having these amazing archetypes nearby and being able to be in a house with them and work with these people that were just super talented and just.

Leveling up my sense of self-worth was really critical. But in the end, I, in, after a couple of years I went back to Japan because I ultimately just felt perverted by the money situation. In Silicon Valley there’s just this incredible amount of money being thrown around and I felt all these muscles I had built up in my twenties of not compromising and not sacrificing in terms of the work I wanted to produce.

I felt them getting whittled away. By being in that environment. So anyway, that was a reason to step back. And then obviously 2016 election was complicated. Everything’s complicated now, and it just feels especially with the walks and what I’ve learned during the walks is that, look, if you stay plugged into this thing, you’re gonna lose your mind.

And I think more than ever, I think 15 years ago, that wasn’t really the case. It felt to me 15 years ago, weird Twitter. To me, the moment it launched felt weird. It felt like something I didn’t want to. Engage with necessarily. I remember like one of a couple of my first tweets were very snarky, like, why am I gonna use this thing?

And even the way it was spelled T-W-T-T-R, it just felt like it was like, fritzing out or something. But now there’s something else that’s happening. I think that is, to me, feels really corrosive. And during the 2020 election when it was Biden and Trump, I did this thing where I walked from Tokyo to Kyoto and I thought I left about a week before the election and I told all my friends, don’t tell me who wins.

I’m not gonna be looking at the news and I, and everyone was, the lead up to that was just like total mania, which the lead up to everything though. I feel like every week is just like another level of mania happening. But the lead up to that one in particular was just like mega mania. And I remember just thinking, man, this is so important.

And some farmer is definitely gonna tell me like, there’s the election’s gonna happen. And then some farmer’s gonna yell out to me like, Hey, did you hear Biden? Got it. That’s what it felt like. With being plugged into kind of general social media, English language, social media, and the election happened and no farmers yelled out to me.

No cafe owners told me anything. No one whispered anything. It was just this weird moment of realizing that you can ensconced yourself in the chaos of things. And that there, there has to be an active level of not disinterest or total disconnection, but of. That you have to engage with today.

And that walk, I finally just messaged a friend and said, okay, you can tell me what’s going on.

Bookstore: And they’re like,

Craig Mod: you don’t wanna know. It’s terrible. All sorts of bad things are happening, but it just helped remind me that not everything in the world that is true is, or the total truth of the world is not contained on a social network, is I think, the important thing I took away from that.

And knowing when to look at it. And to engage with it and to be concerned and change your course of action based on that is really critical. But also knowing when to step away and protect yourself and build up the energy to be able to follow through on that course of action feels equally critical. But the walks were are incredible platforms and tools for learning how to do that.

Dan Sinker: Totally. We have about. Eight minutes and then we’re gonna go to your questions. But I wanted to talk a little bit about, you have in, over the course of the last few years now, right? You’ve built your own social network for Oversimplified, right? Literally. Yeah.

Craig Mod: True. Who hears on my social network.

Ah, thank you.

Dan Sinker: Love it. But you’ve built up what you call a membership program called special projects. Which is. Really enabled you to some degree to be able hundred able to

Craig Mod: that to some degree.

Dan Sinker: Yeah. Completely. So I’m curious, what led to you starting that and how perfect rejection?

Yes.

Craig Mod: Yeah. What do you mean? Yeah, it was like 2018. I was trying to sell some essays. I had this huge essay for the Atlantic. About walking in Japan and I spent all this time on it, and then I got ghosted by the editor and it crushed me again. Like I, if you read this and you find out where I come from.

‘cause I have all sorts of anxiety about class anxiety and wealth anxiety and all sorts of stuff. And so I just always forever am in this imposter syndrome mode. And so when someone like Atlantic Editor ghosts me, that to me just triggers all of these kind of trauma complexes about, oh, okay, I’m not valuable.

I don’t have anything to say anyway. Oh, I was just like tricking myself into believing I should be writing this essay, yada, yada, yada. And so it was in that space. I wrote something for Wired about how digital books are. Terrible and that universe has failed. But within the kind of contemporary digital publishing world, subscriptions have done really well.

And so that, I wrote that essay, I was like, oh, maybe I should look more into subscription software and doing it on my own. And then that led to me calling all my friends who are journalists and everyone was like, dude, just, you should do it. You have stuff you wanna talk about. You have an audience, blah, blah, blah.

Do it. And so that was really it. It was great reluctance. And also I felt like I had used up all of my other options. Because it is so hard to run a membership program and to be self-initiated and self-driven, especially because you really don’t get that many members at first, and it just, it’s crushing and you really have to learn to derive from each person some kind of permission, and it really has to be like on a person by person basis, especially to start.

And I think a lot of people underestimate just how crushing that can be and how much you have to evolve and do different iterations and tests. And, it wasn’t until 18 months into it that I made Kisa by Kisa, and then I realized, oh, if I do I wanna give members a discount. And that was like the first real member thing I’d ever given members.

And Kickstarter didn’t allow you to do that? There was no coupons. And so I was like, all right. I looked at Shopify and I was like, oh, I can hack Shopify to be a Kickstarter. So I made a different version of Shopify’s and I called it Craig Starter. And I was able to give people coupons and and it turned out that to use terrible startup parlance, there was an incredible product market fit between me making cool fine art books and people wanting to be members and support my work and get a discount on the book.

But it just turns out people need that little. Something tangible makes, it’s like the tote bags for NPR or whatever. There’s a reason they do that because it really does. It’s like you just, you wanna get that one little dumb thing and it can mean the world. And so from that, that changed everything.

And the scale of it and the numbers, the, in terms of the business, it’s an incredible business. I’m feel very lucky. And so this, even this book, I retained fine art rights to it, sort of Ryan Cougar recently. Made his movie Sinners. And part of what’s amazing about his contract with the studios is that he retained some kind of special film rights or final cut or distribution format rights.

Dan Sinker: He gets it after 25. He gets full ownership of it after he gets okay, after 25 years. Okay.

Craig Mod: So he gets full ownership back, which is unheard of. And then also he was able to do seven different formats. He shot an imax, he had just total creative control. And so it was like that for me. It’s like I wanted for me retaining that.

Autonomy is so critical because I’m so afraid of people throwing me away. I’m like, so someone’s always gonna throw me away. And having the fine art rights was like a insurance policy so that no matter what happens with this and you really do lose a certain amount of control going with a big publisher, I’m really happy with how this turned out.

And Random House has been great. This really is, represents the peak version of what I think this book could be. So I’m very proud of it and I’m lucky it turned out that way, but I know a lot of people, it doesn’t turn out that way. But at the same time, I am very glad to still have the fine art rights from a business point of view, because even if I sell 50,000 of these, I still make more money just selling a few thousand fine art editions.

And so keeping that which enables me to do more work is, to me, found feels foundational. But it’s been, it’s been interesting, but my, honestly, the membership program is, I couldn’t have done any of these walks. I couldn’t do anything I’m doing, I couldn’t do this tour without the membership program.

That’s who’s, that’s what’s paying for this. Rand House has given me $0 for this tour. So this is entirely out of pocket. This is like a $10,000 tour, like six weeks on the road, Uber’s, flights, hotels, all this stuff. So that’s entirely membership funded.

Dan Sinker: So we’re gonna go to people’s questions in a second, but I feel like there’s a nugget here around.

The fact that there are people spread across everywhere that are raising their hand to say, Hey, I want to help you, do your work. And then that work involves going out and meeting. People at random and just saying, Hey, you know it, it’s people saying to you, I care about you.

And then you’re going out in the world and saying to people, I care about you. There’s a really interesting kind of circular Yeah. Humanity that’s happening in all of this.

Bookstore: Yeah.

Dan Sinker: How much of that is purposeful and how much of that is just who you are?

Craig Mod: It’s definitely not calculated.

It’s just how it happened, but I think the impulse for me to go out to the people and try to elevate those I met along the road. I think a lot about how, obviously I’m a white dude writing about Asia. That’s like a specific, that’s like a certain thing. And in the eighties and nineties there were a lot of expats writing about Asia.

I read a lot of those books and a lot of those books make me really uncomfortable. And so I spent a lot of time resisting writing about Japan. I didn’t want to be. I’m not gonna decode it for you. I’m not gonna show you Japan in a way that you couldn’t figure out on your own or that the Japanese can’t explain for themselves.

So that was always in the back of my mind and I really didn’t do any Japan writing until, really, until 19 or 2019. Yeah, it’s, God, what is time anymore until 20 19, 20 20 ish. And again, it was through great reluctance and it was only when I started doing these big walks. With this mentor, John and John, to me, modeled just such a healthy relationship with the country where nothing.

So I think a lot of these asymmetrical, toxic relationships that expats and I consider myself an immigrant, not an expat because there’s all this sort of stuff layered on top of being an expat that I don’t feel. Any of, but I feel like expats have this weird asymmetry of looking down on the place that they’re living in.

And you got a lot of that in the writing in the eighties and the nineties, and so there’s almost an implicit racism to a lot of the writing and an implicit sort of look at these fools in, just in the way people would write about Japan, even Donald Richie writing about Japan and the Inland Sea.

He hates Japanese people, and it’s this guy who dedicated his life to Japan and, uncovering, revealing awa and Ozu and all this. And so anyway, I very, with incredible reluctance, I thought about writing about Japan and seeing John my mentor and this guy who has an incredible relationship with the country, seeing him engage in this totally, I don’t wanna say authentic, but like he demanded nothing.

And he was purely interested in elevating and learning. That’s it. He’s just genuinely curious about the history of where we were going, where we were walking, and the people along the road and how they interacted with the history. And it was only after walking with John for years that I thought, oh, maybe I can do something like this in my, with my own twist.

‘cause I have a very different background than John has. And so to be able to go at this and and engage with these people in a way of, for me, looking for archetypes of just how can you live your life. That was the great search. ‘cause the place I grew up in, there were a lot of anti archetypes, anti-pattern archetypes.

Oh, the ne oh, the neighbor tried to kill himself again. Oh this friend’s daughter sister is pregnant again. This, it’s just oh, these parents dunno how to deal. Oh, this guy’s drunk this, yeah. So there was a lot of pain and there was a lot of like, how not to be a great parent, how not to be a great father.

And so for me, I was it’s out in the world doing these walks, meeting these people along the way, just looking at their lives and being like, wow, just respect what you’ve built even out here in the middle of nowhere. Even out here in what is just a very simple, not being like reductive of it, but just there’s a beautiful thing that you’ve created here and on this penins.

In this place that’s depopulating, but you still got a certain amount of grace and you still respect what you’re doing and how you’re doing it. And for me that was just powerful to see. And so my impulse was not to, and again, with the language in here too, my translation is I have a connection with North Carolina, Western North Carolina.

I had this strange connection down there and so all the translation of the people on the peninsula, I, I hear in my ear as sort of Blue Ridge Mountain people, like just outside Appalachia educated, but with all the the interesting southern inflections that you can find in kind of North Carolina, South Carolina.

And so my translation of this is I’m not, I’ve not seen anyone translate Japanese people like this because it’s always sort of Tokyo, Japanese, no matter where you are, or there’s this. Over leaning on, I’m gonna, I’m gonna make sure you know that these people are other, and so I’m gonna, I’m gonna inject all these weird Japanese words.

He went to the fuo bath to have a beru beer. It’s, you just, no, just use the language. And so I, when I meet these folks, I really try to just meet them as they are and see them as they are. There’s no oh, look at the weird, this weirdness or that weirdness. It’s look at what’s this amazing life that’s been created out along this path.

In the middle of, nowhere in some cases, and I’m just inspired by that in the same way. I was inspired by moca, which, people living in moca just think this is just a normal little city. To me it was just a freaking bastion of archetypes, of cool ways to live and the way you can have an alternative to Tokyo or Osaka and Nagoya and you can build a creative, beautiful life there.

That’s really what turned me on and that’s ultimately what made me feel like I wanna share these findings. And hopefully do it in a way that everyone who’s represented in here feels honored and loved, and in the same way, I hope Brian, is honored by the way I write about him and kinda shape the book towards him.

Dan Sinker: That is wonderful. When we were sitting in the very small room in the back, Molly was like, all right, you’ve got 6 0 5, 6 45. We need to move to questions. They’re running a tight chip here and I’m very happy to report that it’s exactly 6 45. So we’re gonna move to, yeah, we nailed that. We did a good job.

Good job. I’m gonna move to questions and who’s got some for Craig? I see hat in the back.

Audience: So I’ve read you Wax poetic about JavaScript.

Dan Sinker: Oh yeah. Talk about how important coding is. Yeah. And that sort of thing. And

Audience: so I’m wondering, in terms of things becoming other things, tech maybe being, so before being so like creatively empowering and that kind of thing, and now becoming something that you have to unplug from out of self preservation, how you.

Experienced that transition.

Craig Mod: Yeah, so the question was, tech goes from empowerment to hindrance, right? Obviously it’s very specific pieces of tech, right? And it’s very, it’s more the capitalist infrastructure on top of it, right? The stuff that’s really toxic is the dopa magenic loopy things, right?

So it’s Candy Crush or whatever. There’s something happening in there that’s terrible. It’s very toxic and gets you sucked in or Clash of Clans as I’ve written about, I got addicted to Clash of Clans. I was in Myanmar doing research and they’d just gotten cell phones for the first time and all the farmers were on their buffaloes playing Clash of Clans.

And I thought I should play this and be on a team with the farmers. And then next thing I know, I’m spending like a hundred dollars a day, like trying to buy gems or whatever it was to try to like just beat it. I was like, I just have to get to the end. So it’s this weird layer that we’ve put on top of it.

I remember as a teenager with dial up modems and stuff like that. You download a pirated BBS game or something. I’m downloading King’s Quest four or whatever, and it’s it takes four hours or three hours and you couldn’t do anything else on the computer ‘cause it didn’t multitask. So you could do computer stuff and then you’d have these natural breaks where you go play basketball or go skateboard.

So it was built into it. And now one of the things I started doing, I started smoking two years ago. I decided to take that up and it freaks Americans out so much. If I said that in France, they’d be like, why did you take so long? Americans, I love Americans. You guys hate smoking so much. But if I said I smoked weed, you’d love it.

It’s so weird. It’s so weird right now. But I started smoking two, two years ago, on a lark. I was doing this jazz tour, all these jazz cafes all around Japan, and it’s all these old guys who smoke. And I realized in order I need to ingratiate myself as quickly as possible. So if I just go in, sit at the counter and be like, Hey, can I have an ashtray?

They’d be like, oh, he’s one of us. And it worked and it was great. So I’d become very friendly with these old guys very quickly. I’d, chat, get them crying, I was like a therapist for these guys. And then I realized, wow, nicotine’s really great. Nicotine. Nicotine feels amazing.

And if you just have one cigarette a day, which is what I do, I let myself one cigarette a day. It feels you get a hundred percent of the benefit. And I feel like almost none of the negative, but I’m going with none of the negative. And you get this seven minute beautiful break in the day. And part of my rule for that is obviously I can’t have my smartphone in front of me.

And but what happens is because in Japan especially smoking is it’s like almost like pedophilia. It’s it’s you could do it in this one. Like you can’t do pedophilia anywhere, but you know what I’m saying? It’s very, it’s no, I don’t, it’s very, it’s it’s very, I just mean in a sense like, like it’s so strict about where you can smoke.

Okay. Pedophilia. You can’t do it anywhere, but except in Japan. Who knows? There’s definitely, I’m sure there’s somewhere you can do it. Anyway, let’s move on from that. This is being recorded. We’ll cut that out of the podcast. But the because of that, I have to go to these like smoking areas sometimes, and I’ll go and have a cigarette in a smoking area and I just observe all the other smokers and it is so depressing.

It’s just someone, first of all, vaping is way more depressing than normal smoking. That’s like another tear of like weirdness. And so someone just vaping with TikTok going like this to me, it just feels it’s Vegas. It’s Vegas. We’ve just given up. It’s like some weird, like cosmic teat.

We’re just, we just got our lips on and we’re just so sucking all this dopamine out of, it’s just so bizarre. So it really is how you use it. And so for me, with all these dumb rules, I’ve had to do that because I know person, like from experience, like I just can’t resist otherwise. And my other big rule and the thing I tell everyone to try to do, that kind of gets you started down maybe a less connected road.

It’s just turn the internet off when you go to bed and put your phone. Don’t put your phone in the bedroom. There’s lots of alarm clocks out there. Lots and lots of great brawn alarm clocks that are cool. They look great and they work fine. They wake you up in the morning. A lot of people are like, I need my phone for the alarm.

You can put it somewhere else. You can get an alarm clock. Put your phone not even in view of where you’re gonna be when you wake up and have it in a box. Have it in a drawer charging, and don’t touch the internet until after lunch. And just try to do that a couple days a week. And I find those mornings are, they blossom with creativity and kind of an openness and a weird anxiety.

There’s almost like an apnea that like, this kind of almost like palpations of, palpitations and you get rid of that and you, and we’re so ensconced in it, you forget what it feels like to not be in that. So I’m still generally tech positive. About a lot of things, even LLM stuff, obviously, I’m using it for the membership program and whatnot, but you have to just be hypervigilant ‘cause it’s out to get you

Audience: who has another question.

Yeah. Thanks so much for being here, for writing this book. First off, the question I have is related to something that you said about being so worn out at your end of your day. Yeah. Walking and the thinking and the writing and stuff. So the question is, did you dream. And those things when you, even if you don’t, when you think you are like doing a Japanese or an English?

Yeah,

Craig Mod: I, that’s a great question. I definitely dream, I can’t remember any specific dreams, but yeah, I dream on those trips for sure. But I have to say the anxiety is much lower. Even two weeks ago, I had a dream about talking to a grad, my grad professor, and I had to explain something and I’d forgotten everything.

I learned about the subject and I was woke up in a cold sweat. So still these insane anxiety dreams that you can have. I don’t get any of that. ‘cause it is so you, you just use yourself up so much. And I think, exercise helps reduce that as well, but Sure. I dream and I dream I’d say 70% English, 30% Japanese.

It’s about what the breakdown is.

Audience: Yeah. What did you know about Japan that made you wanna go there in the first place?

Craig Mod: Really not much. Just Nintendo came from Japan. That was sort of it. That was really it. And Nintendo was this island, this bastion of safety, this, in this town I grew up in, that wasn’t particularly together.

Nintendo was an oasis. And I just remember seeing a maid in Japan. Ooh. It was, first conscious awareness of another place. And then my family saved and saved. And then when I was like 13, 14. My I grew up with my grandparents and my mom, and when I was 13, 14, finally, we were able to do like a package tour to Waikiki and Waikiki in 93 was like going to Tokyo.

It was just owned, it was like 90% Japanese. Japanese owned everything. Hawaiians to this day, still hate Japanese people. Because of the amount of economic sort of pressure they pushed, they brought to the islands I think in the early nineties. So it’s very bizarre. We go see Don Ho.

My grandmother loved Don Ho, like crazily loved Don Ho. And so we’d always go to the Don Ho show and he would just have these bizarre racist jokes about Japan. You’re just in shock and, but it’s, I’m 13. I don’t know what’s going on, but I golfed, in America, one of the weird things no healthcare, but you can golf for two bucks or three bucks on a public course.

And so my dad would take, we’d go find balls or steal balls, I guess from golf courses. And and then we’d go to the public course and golf. And so I could golf and I was pretty good at golfing and we’re in Hawaii, and I was like, I wanna go golfing. And I went to the golf course, which was much nicer than anyone I’d been to before.

And I was 14, let’s say I was 14. And you wouldn’t let you play alone. And so they teamed me up with two Japanese businessmen. Oh. And they were maybe in their forties or so. I don’t, I have no idea how old they were. And they were just really sweet and strange, and we got to spend this entire 18 round of, 18 holes of golf together.

And they were like, are you married? I’m like, I’m 14. What are, what’s are these questions? And one guy had a hat on that, that had W-H-O-O-F and then underneath it. It said A-R-T-E-D. And if you read it fast, it says, who farted? And I was just, I was like, do you know what that means? And he’s no, what does it mean?

And I was just, I was like, who are these people? And they were so gentle and empathetic and kind with me. And I made them tell me how to say hello in Japanese. And they taught me, it was like. How, how to say, how to introduce yourself and the thing they taught me was, which is like the longest possible way you could possibly say hello to anyone.

So that was also bizarre. And I remember writing it down and bringing it to school and thinking, I was like, Hey guys, you wanna know how, say hello in Japanese? You said, ha. And so I think it was these things and seeing my tour guide. The Artur guy person in Hawaii speaking Japanese fluently to people. It was all very inspiring and I think it was the first time I had ever seen truly non-immigrant people who had not integrated in any way with America.

So it’s, it was true. There was no attempt Japanese people visiting Waikiki to pretend to even know English. It was everything was set up for Japan, everything’s in Japanese, and so that was. Exciting to see that. And I think when I was 19 and I was thinking about places to go, Europe felt easy.

I go to Europe, I’m gonna I go to England, I can be a British person. I go to Spain, I can be a Spanish person. And so to go to a place where all these things that I loved as a kid, talk about soft power, right? This is the power of doing pop culture and stuff is you in implant, you incept these ideas in kids’ minds.

I just thought it would be fun to go for the challenge. Let’s go to Tokyo. Also, it was really cheap. Like looking at university, it was like $5,000 for the year with a home stay and you could get scholarships and it was like, wow, this is free. Why not go do this? And I applied on a whim and got in and So let’s go.

Yeah.

Dan Sinker: I think we have time for one more question. There you

Audience: go. Forgive me. I incredibly nervous. So I was an explorers club. Never Like when you

Craig Mod: launched Nice. Like month one. I was like, that was the original name of the membership program. I’m here and

Audience: like at this moment is like great to have. So I’m solo backpacker, gen X, landscape photographer, all the things.

Craig Mod: Awesome.

Audience: And what’s your name? David. David. David Sweeney. Yeah. I’m also an adoptee.

Craig Mod: Oh, nice.

Audience: And like when you like, came out, like talking about that like a year ago. Yeah. I see you. I see this. Yeah. And so I think contain like in the arc of your word, like what I see is like this self-actualizing, adopting.

And like I had a son four years ago, most adoptees don’t have kids. And so I’m like experiencing this genetic mirroring Yeah. My son right now. And I know that’s what you’re going through right now too. Yeah. And do you, have you felt like that activating a part of your, like mind and brain that hasn’t been touched before?

If there’s anything that you’d like to share Yeah. Like about that. I’d love to hear that because there’s a language that you’re using and themes in your work Yeah. That yeah, I see you. Oh, I see what you’re doing. Thanks, David. And I’m so incredibly happy for you, in this moment, what you’re going through right now.

‘cause I, the struggle is real.

Craig Mod: Yeah. Yeah. It’s funny, I didn’t engage really with any adoptee. Yeah. Anything. And I think part of it is, as an adoptee, you carry this weird guilt that you don’t want to offend your adoptive parents by searching or looking or thinking even glancing in that direction.

And so you kinda suppress it. And I did this adoption podcast a month ago and talking with Hailey who’s interviewed like 400 adoptees and very interesting, wonderful things she’s doing and talking with her and. Really being the first time I ever engaged with the adoptee world Yeah. Was pretty shocking.

Yeah. And just getting stats from her, even hearing this I’m not surprised, most adoptees don’t have kids. Yeah. Adoptees are four times more likely to do self harm, have addiction problems, things like that. So there’s definitely something Yeah. Embedded in that world that I had never touched.

And part to your question about like, why Japan? Why did I stay there? A big part of it was walking through Tokyo. Passing tens of thousands of people a day through like Zuku station or whatever, and not feeling the struggle that I felt back home and feeling like everyone could only fall this far. There was like this implicit net underneath us all.

That was one of the most moving things I ever felt. And so to be ensconced in that kind of protective layer, that protective place was really important to me. Because as an adoptee, you’re constantly battling with, everyone’s gonna throw me away. That’s a huge fundamental feeling.

It’s so when the, I got ghosted by the editor, it was like dark times.

Audience: Did you know Steve Jobs was also an adoptee? Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I really, I You should tell a story. Read Isaacson’s biography.

Craig Mod: Yeah.

Audience: In that lens. Boy, you really get it.

Craig Mod: Yeah. It turns out, yeah, there’s a lot of tormented adoptees who are insanely driven.

So a big part of it has been to transmute those feelings into something positive. And for most of my toys, I didn’t know how to Yeah. And so I drank myself into the ground. Yeah. It was just like alcohol. And I get why propensity towards addiction is so high in the community because it is, it’s so hard.

And then your kind of adoptive parents aren’t really schooled. In a way to help you. Yeah. And no one is really trained to be as present because it takes so much work to, I think, bring an adoptee to a healthy place. And no, almost no parents are capable of doing that. And then especially when you compound it with, my parents got divorced when I was two and blah, blah, blah, blah, and all this other stuff.

You just constantly in this mode of. How do I protect myself? How do I protect myself? And so Tokyo also felt because I’m not Japanese, I’ll never be Japanese, and I can not be thrown away by a place that never access me in the first place. And so that was very comforting. And so in my twenties, that kept me there.

That really kept me there. And it just turned out too, that Tokyo was a wonderful place to build a creative life because cost of living was so low. So my rent was never more than $600 a month, and I was able to live in the center of the city. And so that’s been really exciting. And then the last couple of years I’ve had some interesting experiences where I’ve met family members, birth family members for the first time.

And like in Seattle, for example, my sister flew down and came to the talk. That was the first time we met at the event. And she had six months ago said, I don’t want to connect. And then three months ago said, oh, I thought about it. And she’s 28. And lives in Alaska and she’s married. And we did one video call and it was both just we were both just whoa.

Like we, she’s an only child. I’m an only child. It was like, wow, we really each other. And immediately she messaged me after she said, Hey bro, can I call you bro? And so she came down and and then we, the next day we went for a walk in the pouring rain in Seattle and it was just. It was sweet, and you kinda see this, the, this optimism in her, this kinda we’re gonna do this.

It’s pouring, it’s disgusting, it’s freezing. And she’s let’s keep going. Let’s go to the top. Even her husband who’s in the National Guard was like, Hey, I think we should turn back. And and then in, in New York, my aunt and uncle came who I’d never met before, and, they messaged me and they’re like, Hey, we wanna take you out to lunch before the event.

Can we take you to Benny Hana?

So it’s been, it is just been very, it is been very bizarre to suddenly go from zero family. My adopted family’s so small to the now suddenly. My, my birth mom has four siblings and there’s all these aunts and uncles and all these cousins. I’m getting Instagram dms from people in Wisconsin who are like, Hey, I found out you’re my cousin.

I’m 33. I run a flower shop. Like I, I’ve got one kid. I’m like, this is so weird. So it’s, as Hailey says in the podcast, she’s off, off air just saying I’m pretty lucky because not all, family kind of connections. Go pos in positive directions. Even she connected with her birth mom and then three months later, her birth mom was like, I don’t wanna talk anymore.

It’s like on both sides of the table people are carrying so much pain and trauma. So I, I’m lucky in that I was 43 when I like entered into this bizarre sort of new phase of life and a lot of the stories I told myself about my origin are being rewritten in real time and about who my people are and things like that, and feeling.

I think if I was in my twenties, I would want more out of it. And I’m really lucky in that I have a stepdaughter who I’ve had this incredible experience growing with, growing together. When she’s 15 now, we just did like a 90 minute video call last night. I had to turn the video call off which I feel like is like a very rare position for a parent in a 15-year-old.

And she was like going through her whole photos gallery and showing me every photo she had take and telling me every story. I was like, okay, great. I’m glad we have a good relationship. But like in going through things with her and growing and then through the membership program and feeling the support of you all, especially, early members and stuff like this, I think has brought me to a place of peace in a way.

It’s something I didn’t have 20 years ago and I could not have engaged with this in the way I’m engaging with it now, and I don’t need anything from it. So when my sister was like, Hey, I don’t, I can’t connect. Great. I totally get it. That’s cool. Yeah. I’m here if you need me. That’s fine. And being able to say that without any ego or any, there’s no ego involved at all in it.

It felt really good. And to be able to meet these people and to think in a non narcissistic way, boy, I’m really glad they get to meet me as I am today. They’re a part of your story. Yeah. But being able to feel that was a really profound moment. And it’s weird. You don’t think things like that unless these weird catalysts come up.

So yeah, pretty cool.

Dan Sinker: It’s,

Craig Mod: yeah.

Dan Sinker: Thanks. All right. I see Molly standing over there. I got you. I’ve got you, Molly. That brings us to the end of this conversational part. Craig, thank you so much. Thank you for taking part. Thanks all of you for.