Episode 3

Prose and Politics — DC — Ross Andersen

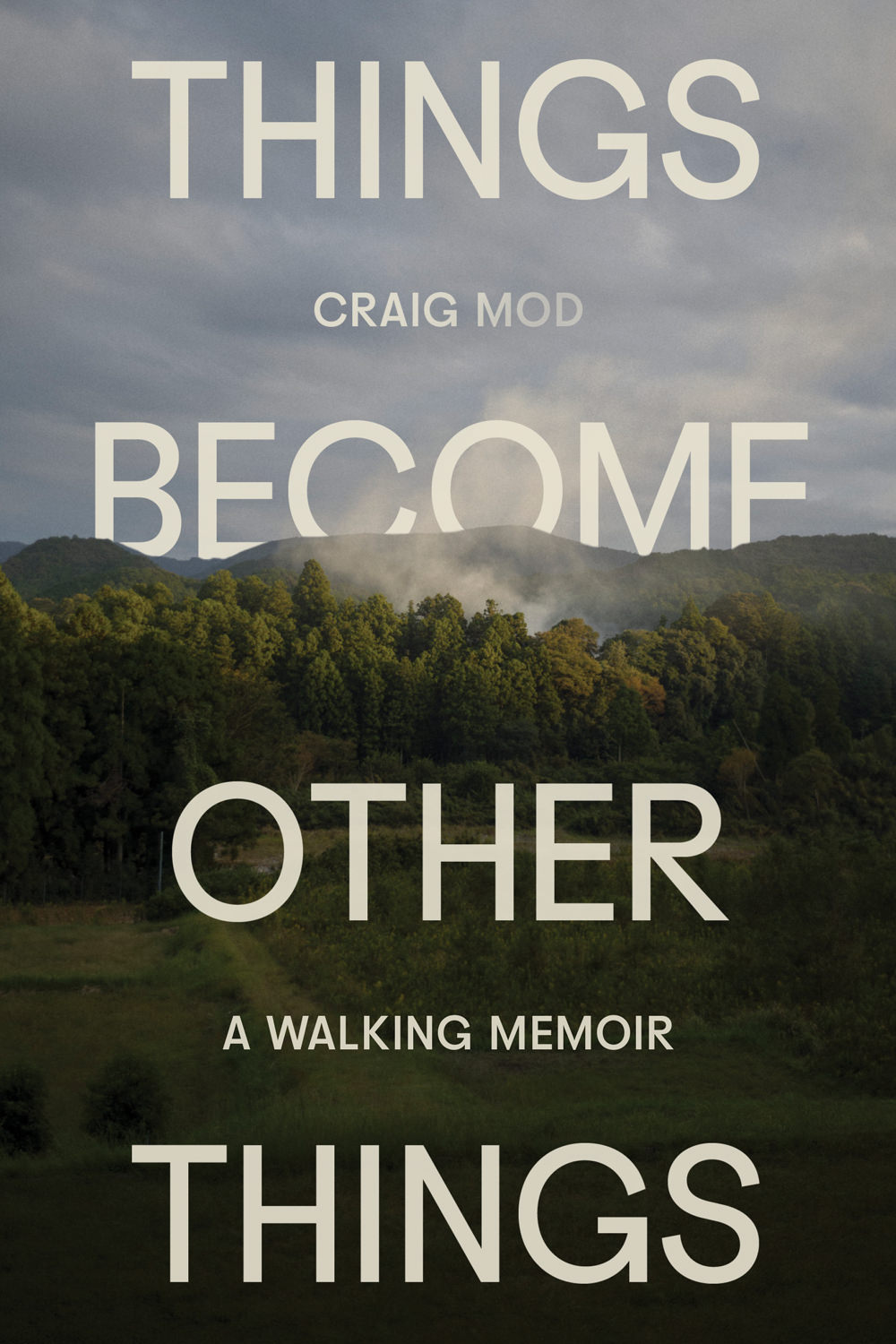

Craig Mod in conversation with Ross Andersen at Prose and Politics in DC, chatting for fifty-nine minutes on May 07, 2025

Ross Andersen — editor and staff writer at The Atlantic — and Craig discuss Craig's new book that defies traditional genres. Initially thought to be a travelogue, the book turns out to be a profound grief memoir intertwined with reflections on American culture and philosophy of walking. Craig discusses the origins and structure of his book, which was inspired by a need for stillness prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, his deep connection to Japan, and his long walks on its pilgrimage routes. Craig continues to describe his process of blending vivid travel experiences with meditative writing, the influence of Japanese cultural concepts such as impermanence, and his continuous effort to maintain creative rigor. The conversation also explores how different lengths of walks impact one's mental state, the importance of setting self-imposed deadlines, and the role of film photography in his creative work.

Guest Links

Chapters

- 00:00 — Introduction and Opening Remarks

- 00:30 — Introducing Craig Mod and His Book

- 01:24 — TBOT's Themes and Structure

- 02:37 — Craig's Writing Process and Inspirations

- 06:18 — Personal Reflections and Bryan's Story

- 11:23 — Craig's Journey to Japan

- 19:14 — Pilgrimages and Walking Experiences

- 26:59 — Philosophy of Walking and Meditation

- 28:34 — Meeting John McBride: A Life-Changing Connection

- 29:10 — Walking Pilgrimages

- 30:24 — Solo Walks and Vipassana Meditation

- 32:31 — The Profound Impact of Extended Walks

- 37:45 — Reflections on Daily Writing

- 42:37 — Embracing Impermanence and Japanese Traditions

- 45:48 — Rules and Practices for Meaningful Walks

- 50:16 — Balancing Work and Walking

- 55:08 — The Return to Film Photography

- 58:44 — Conclusion and Book Signing

Subscribe to the Podcast

Transcription

Craig Mod: Hi. Hello. Thanks for coming out. I’m always like, three minutes before I’m like, no one’s gonna show up.

Ross Andersen: I, done a lot of these and usually don’t have this kind of response. But we got Craig Madden come on in the house tonight, which is exciting. All the way here from Japan and I’ve admired Craig a long time and have had the good fortune to be his friend now for 10, 15 years,

And I’ve also been very lucky to take walks with him both in this city and in Tokyo. And yeah, he’s just a wonderful guy and I. As a fan of his, I was so looking forward to this book, I really was, but I think I had a boxed in idea of what it was gonna be. Like I was, I’ll write, Craig could go down to the convenience store, to get a coffee and I’d read an essay about that experience and I thought that was be like a kind of straightforward Craig travel log in Japan.

And I was really astonished when I read the book, how much is in this I dunno if, has anyone read it in here? Okay, we got. A few. Yeah. This is like a grief memoir, it’s a philosophy of walking, it’s a kind of soul level critique of American culture and why one might wanna leave it.

And it’s written in just really beautiful language. Anyway, it’s an achievement. I’m excited to dig into it with Craig tonight. I know that Craig, in dc. And in kind of any city worth mentioning, there’s a big Craig BOD fandom and I want to make sure that some of you all get to ask some questions.

And so he, and I’ll go between kind of 30 and 40 minutes and then I’ll open it up to the larger crowd. Craig, congratulations, Ben.

Speaker: Thanks.

Ross Andersen: I wanna talk about Brian. I want to open up talking about Brian. As I said I had first thought this book was a travel log and. In fact, it’s a grief memoir and it’s really epistolary, which is to say that it’s directed at this character, Brian, not a character, a friend from your formative years.

And I just hope that you could talk about why you thought to structure the book that way, and also tell us a little bit about what was going on in your life in 2021 when you started writing this book and what kind of called Brian back to your mind.

Craig Mod: Yeah. So you know this book, I’m sure some of you have been following along.

This book has been through many stages. I started it essentially on the walk. The walk that became, this book began exactly four years ago, tomorrow, so May 10th, 2021. So it was the height of COVID. Everything was shut down. Japan was basically Ed closed. No one could enter. If you left, you couldn’t come back.

So I was kinda stuck there, but I loved it. I really loved it. I was, because I was able to I wanted to stop moving for a long time. There’s this kind of momentum that life picks up and in 2020 I had, I think 11 international trips planned, and then suddenly it was all shut down.

It was all closed. And for me, I think I needed that kind of third party, that almost like natural intervention to happen. And then that was when I started working on Kea by Kea and had that book come out. And then a lot of momentum came outta that. And I think I, I drew a lot of kind of permission and. I don’t know, just excitement about that energy.

And so I did a walk when Biden and Trump were going through the election bit in my, I had a rule where I was like, no, no news, no social media. And my theory was that I’d be walking, my walk started like a week before the election and the election would happen and then some farmer would yell to me the results.

I had this idea. ‘cause we were also so obsessed with it.

And no one in Japan. Yelled me the results. And so finally, a week after the election I said, what’s going on? I texted someone, I texted my friend Sam. So I was doing those things. And then the walk four years ago was, I wanted to go back to this peninsula that I’ve been visiting for years and years.

I’ve been many times, and this was a walk where I was trying to connect all these disparate paths that previously walked and do them all linearly to a certain degree. And so the world was just, there was a quietude. To that stage, and Japan was counting, how many cases of COVID and all that.

And mi pre fixture, this is a peninsula south of Kyoto and Osaka. So MI and Guama and Nada. And MI had three cases. It was like, it was very, it was just a strange energy.

Ross Andersen: Yeah.

Craig Mod: But we were all really concerned. And I was testing and I was making sure I was careful.

And I was like, all right, lemme go on this walk. And so it was in this landscape of real. It surpri, like extra silence. It’s already a pretty quiet peninsula ‘cause of depopulation, aging population, things like that. But 2021, it was extra silent. I think every inn I stayed at, I was the only guest and all the cafes and restaurants had signs on them that said, we don’t accept out of pre fixture customers.

So it was very, it was a weird energy. Yeah. And so I was just in the middle of that and I was doing my pop-up newsletter for that walk that I started essentially drafting. What became this book? But it went through another whole drafting sequence. I thought I was gonna finish this in 21 days.

Started, so I did the walk, came out of the walk with about 50, 60,000 words. And then I was like, all right, I’m gonna take these 50,000 words, I’m gonna turn them into a book, and I need to do that quickly. I need deadlines. And so I set this deadline of 21 days and I started a newsletter called Nightingale Andal that was gonna document it.

I was, oh, diary, every day I’m gonna, for 21 days, I’m gonna write about what I did, and the book will be done. And I just sent out issue 298 or something out of 21. But during the process of revisiting the source material and then turning it into kind of book form, I had one reader, Ali Chance, who’s a old friend from college, and he’s a incredible translator and writer.

He was reading drafts and Brian was starting to sneak in.

So he wasn’t present explicitly in the pop-up newsletter. Because it is so personal. So Brian was basically, I’m adopted, I’m an only child. You want brothers and sisters when you’re a kid, and so Brian, we met in first grade and we just fused as kids can do sometimes.

It was just, okay, this is my person. I love this guy. And all through elementary school, we were just totally fused. And then you start testing and if you test better, you go into a slightly different section of the world of certain places. And my town was not well funded. And there’s a lot of struggling.

And if you didn’t test well, you ended up in this dangerous, more dangerous area. The whole place was to a certain degree, dangerous. And we just were cleaved by the system apart. And then when we graduated high school, a week after we graduated, he was at some party, got in a fight and was murdered.

And this other kid. And so we were 17, we just graduated. Life is, oh my God, we’re done with high school. Can’t wait. Let’s go out and be adults. And he’s. Finished just like that and in, in such a stupid situation. And when I was 17, I didn’t have the tools or the people in my life to process that with.

And I, in that moment just lost half of my, essentially my childhood heart. All these memories that I won’t be able to access. ‘cause it’d be through conversation with him that they’d come out. And I think for many years I tried to write, the first short story I ever published was actually a short story about Brian.

And so I was trying to go there. I didn’t know how to, and 25 years passed and I was four years ago doing this walk. And I think it was in that silence, the concoction of COVID, the stillness of all that, that I finally felt like, okay, maybe I can revisit this. And then Ali, who was that reader, was saying, Craig, this is, Brian is poking out here, and that’s what I want to know about, I wanna know about Brian.

So he really helped draw that out for me.

Ross Andersen: One of the lovely things about that is that your relationship to Brian serves both as a kind of a spiderweb that like you, you can attach other relationships that you had during your childhood too. So it works. Brian works as like a real vehicle to excavate your life when you were younger, but also, which had many difficulties as you say and which the relationships you had then were not ones that you wanted to.

Reproduce in your later life. And so the other nice thing about this book is it’s also about the kind of relationships that you’ve been able to form since, and I wonder, as Brian was emerging as a stronger theme in this book, when did you start to realize that he would be the map to all these other relationships?

Craig Mod: It only happened after I finished one version of the book. So it was I, my random house deal is unique in that two years ago when we inked it. I was in the middle of producing the fine art edition because I didn’t think anyone was gonna wanna buy this. So I just decided, all of my life, I’ve been working in indie publishing and doing fine art books, and I just know how to do that.

And I have relationships with printers and I have a distribution network. It’s very easy for me to do that to a certain degree. And so I was deep in producing the fine art edition and then Random House said, Hey, we love it, we want it. And I said you could have it if you let me keep fine art.

And they were like hold on, give us a couple days to think about that. And we were able, look, my, the fine art edition’s a hundred bucks, yours is gonna be 25, with discounts on Amazon or whatever. We’re not competing. And so they let me do that and I put out the fine art edition 18 months ago, and I didn’t realize that, finishing that, completing that, and then, there’s a kind of tension that you can have when you’re writing certain things.

And by doing that, I was like, okay, I got the version out that I wanted to get out. This is like minimalist. We really pared it down. There’s almost no characters except for me and Brian doesn’t. The epistolary component of this book doesn’t appear until the last, say, 30 pages of the fine art edition and going back and working with Molly Turpin, my editor, random House, and our kind of strategy was she went through that edition and asked questions throughout the whole thing.

So she littered the manuscript with three, 400 questions. And then to get to this version, I was responding to all those questions. And then also going back to that, having given it, six months, seven months of kind of space, the energy of the last 30 pages that turned to Brian. I just said, this is crazy.

What if we obviously pull this up? It’s like Annie Dillard, it’s don’t save anything. Don’t, if you have something good, put that in the front. So I pulled up the entire framing of the book from the fine art one where it tiptoes towards Brian, and then the last 30 pages.

Turn towards him to the first page of this book is Brian. And it’s a story to Brian and then in being able to do that, because he is foregrounded, I’m able to bring in these other relationships without it diluting Brian.

Speaker: Right.

Craig Mod: So the whole thing can be talking to, explaining kind of the memoir component of it as a letter to essentially this friend who I’ve lost and now I’m catching up with for the first time in 25 years.

Ross Andersen: Yeah. During that time in your childhood, when was I, when you were in this environment that you’ve come to see as being deeply flawed, you were anxious to get out. And eventually, and I’ll let you tell the story, it’s not my story to tell, but you decided to up and move to Japan, and this is more than 20 years ago now.

And I wonder having had many versions of youthful naivete, myself. What was your image of Japan at that time? Like, where did you think you were going? And you have this great detail in the book where you talk about seeing a Nintendo cartridge, like a Zelda cartridge and it saying made in Japan on it and this having this kind of futuristic glamor to it.

But talk about what did Japan represent to.

Craig Mod: Almost nothing. It really was. I had no, we were, yeah. I grew up in, in a very inward looking place, so there’s no international element to anything. And like you say, Nintendo was everything to me as a kid, and for Brian as well.

And it was our escape. And I think, video games are great at this. If you’re in a situation you don’t like being in, you can escape into this kind of virtual world. Books work that way too. Video games are maybe even more accessible and, so for me, it just represented this place that created a thing that I loved that was so dear to me.

One of my earliest memories, this is a psychotic memory to have, but super Mario two was coming out and my, my parents, I was adopted and then my parents divorced almost immediately. It’s like kind of bizarre that they decided to adopt and then split. And then I was coming home. My dad was driving me back after a Saturday, after Burger King eating at Burger King with him.

We were driving back over the Connect Connecticut River. And I just remember it was Christmas Eve or something and I was just going, Mario Madness. Mario Madness. It’s I had this, I was just so excited to get this game. I know we were gonna get this game for Christmas, so it was this beacon of joy from this place that was far away.

And I managed to somehow subscribe to video game magazine from Japan somehow. And it came and I thought it was gonna be in English for some reason. It was obviously not in English, it was in Japanese. And so it was, anyway, it was this mysterious place that was interesting and. Through random chance.

My I was raised by my grandparents and my mom and everyone worked at the airplane engine factory in town. My mom was an elementary school teacher and everyone just saved. And when I was 13, 14, my grandparents had this sort of bizarre desire to go to Hawaii. And in 1993, this is the height of the Japanese bubble, Japan owned Waikiki.

I don’t know if any of you are familiar with the history and how Waikiki sort of the ownership has shifted, but in the early nineties, everyone was worried Japan was gonna buy everything. It was buying golf courses all over the world, buying, movie studios and so we landed in Waikiki on some.

Extremely cheap package deal, like everything inclusive for a week. And it was essentially like visiting Japan. It was just, it was very mind blowing because it was 50, 60% Japanese people from Japan, like real Japanese. My, my town is really diverse, the place I come from, but everyone sort of first generation, second generation, it’s a big mix with Vietnamese and Laotian Indian, Puerto Rican.

It was just like this really interesting melting pot, but to go to Waikiki in 93. It was vis like visiting Japan. Anyway, that, so that really stuck in my mind is these people are really interesting. I went golfing in, in America you can golf on public courses for five bucks for 18 holes.

And so I went to go golfing in Hawaii and they don’t let you do it alone as a 14-year-old. And so they paired me up with two Japanese businessmen. So I’m 14 and it’s these two 40 year olds. They could have been. 28 for all I know, but they felt 40 to me. And they’re asking me things like, are you married?

And I was just like, who are these guys? And they were super sweet. And they, and I said, teach me how to say hello. And that’s that’s what they, that’s the, they taught me like the longest possible you could say hello. And one of ’em had a hat on that, that it said W-H-O-O-F. Yeah.

I said, do you know what that means? He goes, I, he goes, I don’t know. I don’t know what I just bought this brand hat and it said it had W-H-O-O-F and then the second line. A-R-T-E-D and if you read it together, it said, who farted? And I was just like, who? Who are these people? There’s there. They were so nice and it was so bizarre.

And I, I think that also stuck in mind when I was 19 and I was thinking about dropping outta school and I was looking for, okay, what can I do? What are certain options? I looked at Japanese universities because I wanted to study abroad and I thought it’d be more interesting to go to Asia as a challenge and it was cheap.

I think it was like 5,000 bucks for the whole year with a home stay or something, and you could easily get a scholarship. And I was just like, oh yeah, why wouldn’t I, why wouldn’t I go do this for a year and see how that goes? And so I did. 19,

Ross Andersen: I was gonna ask you how your sort of thinking about Japan has changed and the time since, but that’s like the subject of 10 books.

So why don’t I narrow the question just a little bit and ask you, you’ve come to know Japan. To a really uncommon depth, I think for a westerner like I’ve walking around Tokyo with Craig. It’s funny because you’ll go to a little market or something and someone will be like, like messing with groceries and their back will be turned and Craig will ask them a question in Japanese and then they’ll turn around and see him and just be astonished.

And so you’ve got to know this culture really well and what. I guess your image of it, how is it different than the image that most Americans have of Japan today?

Craig Mod: It’s not futuristic at all. It’s like the big, everyone thinks Blade Runner and it’s just so hopelessly not technologically that competent really interestingly, there’s a lot of things they were really ahead of the curve on, but I think in 1985, Japan felt like it was living in the year 2000.

And then today it still feels like Japan’s living in the year 2000. So it’s this sort of bizarre concept of contradictions. And there, the reason when I landed at 19, I think what I felt intuitively that really kept me there or made me think maybe I should spend more time there was, I’m commuting from my home state, family’s house to school, and I’m passing through Shinjuku Station, which is the biggest station I think of the world by in terms of passengers.

And I’m passing tens of thousands of people every day. And I just had this sense. That people were taking care of this ambient sense oh, I had never felt that before. People being taken care of, ‘cause a lot of thinking back on, on my town where we grew up, everyone was suffering.

Everyone was like just barely scraping by. This neighbor just tried to kill himself. This guy’s an alcoholic. This, this friend’s sister is pregnant. Oh, that person’s pregnant. Oh, this person, got shot or whatever. This guy’s in jail. It was a sense of. No one was there to protect us.

And then I go to the city, this giant massive machine of a city that’s bigger than anywhere I’ve been in my life. And all I can feel is this ambient sense of everyone I’m passing can’t fall that far. Of course, it took me like 20 years to realize that’s what I was feeling. But yeah, that’s, that was a pretty profound thing to feel and I think it made me want to explore and it made me feel safe and protected and that was a place where I could.

I feel like I, I felt like I didn’t have the archetypes or the resources to rebuild myself in the way I wanted to, or to become the person I wanted to become back where I came from. And it felt like Japan, even though it would never accept me, I’d never become part of Japan fully. There was a foundation there and the cost of living was so low that there, there’s a freedom out of all that felt potent and exciting, and that’s why I ended up spending my twenties there.

It just felt like a good place to do that.

Ross Andersen: Yeah. It seems to have worked out. Yeah. This walk that you take in this book takes place on the peninsula and, I was gonna try to pronounce it, but there’s like a big riff in the book about pronouncing it and screwing it up.

So I’m gonna let you do it key, but like with the x-ray. See, tell him though. Tell him the trick. It’s just,

Craig Mod: it’s got two eyes.

Ross Andersen: So

Craig Mod: you elongated a little.

Ross Andersen: There’s this pilgrimage route, right? The cuo codo pilgrimage route, and it’s one of two in the world that have UNESCO World Heritage designation as like pilgrimage routes.

The other one being of course, the Camino de Santiago in Spain. And Craig is one of the very few people, you actually get a button if you pull this off, who’s done both. And I was hoping that as someone who’s now. Thought deeply about pilgrimages and what goes into a good pilgrimage, if you could compare and contrast them for us.

Craig Mod: Yeah I got the badge. I’m on the website. If you search the website for dual pilgrims, I’m on the Dual Pilgrim website. That was a very exciting moment, but actually I didn’t walk the full French Camino. You only have to walk a hundred, like a hundred KA bit. So I feel like I’m a little bit of a charlatan.

Yeah. I didn’t do the full stolen Valerie, the full Camino, but I went. To do the Camino parts of it. And I was really su suspicious of it because it is so popular, and there’s that terrible Martin Sheen movie the Way where Emilio Este Estevez dies on the first day of the Camino. And I’ve walked.

The day that he died on. And you just have to be terrible at walking to die. So it’s just a weird movie. It’s such a bizarre movie. And then someone keeps yelling, you’re a boomer. You’re a boomer. So like to one of the characters, it’s so bizarre. So I had this image of it just being terrible and Disneyland esque and overly scrubbed and not really having that much juice to it.

And I started in French, I walked over the Pyrenees and I did basically 120 30 K of that. The first bit of it. And it was just magic, man. It was magic. And no matter how popular or how many books, everyone’s I think everyone’s telling me that it’s more popular than ever.

Now. It’s popping up on TikTok and social media more and more. But to do it takes five weeks to do the whole thing. To do something like that, to set off on something like that and to commit to it, it doesn’t matter how scrubbed the path is, that’s a huge undertaking and you feel it, and everyone feels like you’re part of this incredible.

Bizarre family where you don’t know anyone, but you’re all doing the same thing. You’re all moving towards the same goal. And I left, I’d only scheduled the first, that first 120 K or so and I left, had to extract myself from it. ‘cause I was gonna meet Kevin Kelly and we were walking the Portuguese way.

So the last 110 K from the Portuguese border up to Santiago. And I was heartbroken. I didn’t wanna leave. I was really ified. I was like, oh my God, I just wanna stay. I wanna keep doing this. So that was a shock. And then Kevin Kelly and I, we did another walk and talk just two months ago, and we walked the last 110 20 k of the French Camino.

So now I’ve walked the Hun first 120, the last 120. And even the last 120, which is the most touristic, it’s the bit that everyone just goes to and walks. ‘cause you can get the pin if you do Yeah. If you do that bit. But even that bit was pretty good. Was pretty good. So I’d say if you’re thinking about doing a pilgrimage or doing any of these walks, the Camino, and if you can do the full Camino.

Do it and do it alone, because it’s really constructed for the solo walker. And you’re gonna meet people and it’s gonna be incredible. Now, the, like the Camino de Santiago Kano Codo also it’s not one route, right? So when people talk about the Camino, there are the 99.9% of the time talking about the French Camino.

And when people talk about Kimo Codo, they’re mainly talking about this root called the naka hiti, which is just one tiny bit of Kimo cordo. But the whole thing is it spiders out from Hong, this area, this shrine, Hong Taysha, Hong Grand Shrine, like the Santiago. Also, everything kind of spirals out from Santiago.

So there’s a Portuguese route, there’s the English route, there’s the French route, there’s a northern route. There’s all these different route to the San, to the Camino de Santiago. And so like that, the Kimo is similarly complicated and it took me years to understand and be into to hold in my mind what all these different roots were, which is part of what this walk was about, connecting a lot of those disparate bits. But when people talk about, I walked to Kudo, they’re really 90 most of the time saying they walked nakai. And the big difference is, the Camino is full of all these villages, the ancient villages, tiny villages with these incredible cathedrals that took generations to build that have been there for a thousand years.

And Japan is all about wood. And wood just disappears. And a lot of Japan is about rebuilding. And so you don’t have that ancient village component on the kimono, and it’s much more animistic and in conversation with nature itself. So a lot of the shrines are shrines to a waterfall, to a rock in the mountain, things like that.

And so those objects have been there for millennia. But the structures of the shrines themselves, the inns, you stay in the towns you visit. It doesn’t quite have that same epic historical resonance that you get on the Camino,

Ross Andersen: huh? Yeah. You talk about all the, sort of the long tradition of pilgrimages in Japan and in thinking about what previous pilgrims had written about those journeys, like how did you think about yourself?

Could have been conversation with them

Craig Mod: in, in 300 years ago, 400 years ago, if you wanted to travel in Japan. It was actually quite complicated. You needed a passport. They’re dio and they’re the domains and everyone was it was a lot of civil war happening. And then post civil war, everyone was worried about more civil war happening.

So it was fairly strict to go on a trip if you wanted to go on a trip. And so the easiest way to go was, say you wanted to do a pilgrimage, and anyone, if you had the money to do it, they would kinda let you go. Yeah. So a lot of the, a lot of the old roots in Japan are these pilgrimage roots and I am not interested in.

Walking, say the Appalachian Trail. That’s not interesting because I want to talk to people, I want to meet people. I wanna see lives being lived. That’s really important to me. And so the cool thing about these pilgrimage trails is because they were so frequently walked, they were the highways of Japan.

There is this all of the main, cities and a lot of, mid-sized cities today that remain, are along these roots and a lot of villages. And there’s a lot of, especially on the KI Peninsula, you get a lot of. Fishing villages lumber villages. There’s a lot of, there’s a lot of working class kind of blue collar energy to, to the roots.

And so you get that spiritual component, but you also get to meet people that feel like, that they’re embedded in the land themselves. And so for me that’s critical. It’s not just about going into the mountains and doing some kind of mountain aesthetic training or something like that, which I’ve done and is interesting, but it’s really every day I wanna talk to, a dozen people if I can.

And even if it’s just a hello or short conversation or whatever it might be. One of my things is that I try to take a portrait of someone by 10 in the morning. And so if it’s 9 45, I’m I have all these rules that no one’s holding me to, but, I have a covenant with myself and it’ll be 9 45.

And it’s a, it is just a good forcing function to yell out to a farmer. Hey, can I take your picture? Or, knock on someone’s door or, open a to Tommy’s shop, knock and see if they’re getting going in the morning yet, and to start that conversation.

Take that photo and catalyze the energy that comes from connecting with a stranger that then infuses the rest of the day. It’s such a powerful thing to feel that.

Ross Andersen: As I mentioned at the top, this book doubles as a sort of. Thoro Vian philosophy of walking. And I want to read one very short passage in particular.

Craig says, there’s no quieter place on earth than the third hour of a good long day of walking. It’s alone in this space, this walk induced hypnosis, that the mind is finally able to receive the strange gifts and charities of this world. I wanted to know, Craig, at what point in your walking life that really clicked in for you?

And also how that experience compares to known you a long time when you’ve experimented with various types of meditation. What do these things have in common? How are they different?

Craig Mod: Yeah. I had all, when I moved to Japan I spent many a night very drunk, walking around Tokyo, and I think that was when I started to notice that there was something potent.

About the walking. Yeah. But it took me a long time for it to be formalized in any kind of real way. And I had to kick alcohol in my late twenties as well to get to that place. And it was really through my friend John McBride, who’s this Australian guy. He is long history with Japan. He’s been there for, or he is, been connected to it for 40 plus years.

He helped, he was the CEO of Sky TV in the nineties when he was 34, I think he became CEO, this real magical, pulsing brain of, but also so generous and such a beautiful guy. And we connected because I did an art book about the Tokyo art world. And he was involved with the art world.

He’s gifted many pieces to galleries around the world and he catalyzed the whole when aboriginal art in the early two thousands was making his way around the world. This is all sort of John McBride behind the scenes making this happen. And we connected. We sat down for breakfast about 17, 18 years ago.

And we didn’t get up till yesterday. Basically we didn’t stand up until 5:00 PM or something. They ended up kicking us out ‘cause they had to get ready for dinner. And it was just one of those immediate, okay, this guy, we get each other. It’s, it was really nice. And so he started inviting me to the peninsula.

He’s the one who I had never heard of Koto. I didn’t know anything about these pilgrimage roots. I was about 30, 30, 31, I think, when I was first invited. And I spent a couple years just walking with John. We’d spend a few months a year walking together. Just the two of us and doing these roots. And he was doing research.

He works with this company W Japan and a lot of WP Japan’s roots Koka pilgrimage, the AKA route, the OK mic, ba route. A lot of the Koto stuff, John built those walks and helped establish them for w Japan to helped build those relationships. And so I was watching John do this work, and he studied tea ceremony for 40 years and like he’s, his classmates became like prime ministers.

It’s this level of. Almost like Forrest Gumpy in life that this guy’s lived. And so watching him talk to these farmers in sort of tea ceremony Japanese, which is pretty elevated, but just using these phrases that, no one has ever used on these farmers before. And watching them flip over the swing set of disbelief and just fall in love and want to help us immediately switch from being circumspect of us or suspicious of us to John just deploying historical fact.

And doing in such a way, in such an elevated way with so much respect to them becoming total allies, like in, in just minutes. And so I watched that for years before then I thought, okay, let me, lemme try walking on my own. And and then I was walking on my own where I thought, okay, this is something interesting is happening here where I can’t access this place where I’m with John and or when I’m when I’m with anyone.

And I just started riffing from there. I think the first big walk I did on my own was 20. 16, which I did right after Vipasana retreat. So I did, I went and did a 10 day vipasana because someone invited me to this talk by some guy named Yuval Harari and at Stanford like 12 years ago. And they said, oh, you should come.

This guy’s gonna give a little talk. We invited him and it was, I was in a room with 10 people in Yuval and he comes out and he’s laser beam brilliance. Come, this. Just who is this guy? And I, looked him up and he does two months of vipasana year, two months every year.

And I just thought, okay, if this guy who’s Obama’s singing his praises about his book and all this stuff, if he can find in his life two months of time to go do this, I can find 10 days. ‘cause I’ve been putting it off for a long time. And so finally in 2016, I did it. And it was pretty profound to sit for a hundred hours over 10 days and sit and focus your attention, scan your body, and just think about how the physiology of emotion happens before the psychology of it.

And and becoming good, really attuned to what you’re feeling in your body when you’re feeling it, and short circuiting those physical sensations from going straight to the brain and causing you to react. So basically vasa is almost like this training. Ground where you’re using your body as the sitting for a hundred hours as this kind of training ground to have an experience, have an emotion and say, wait a minute, okay, I wanna make sure my response to this is aligned with my goals instead of just letting yourself respond.

So the physicality. So I had just done that and then I set off and I think I did eight days. That was my big walk on the Kimon cord, going back to roots I’d done before. And so I was in that mindset and so the two sort of merged, began to merge. Yeah.

Ross Andersen: Huh. I want to make sure that there is time for other folks to ask questions.

So I’m gonna ask one more question and then turn it over to all of you. It seems to me that, at least in these last 10 years, you’ve become an expert on the quaia of walks. And I wondered if you’d tell us how an eight day walk differs from a two week walk, differs from a 30 day walk, and then culminating in this 40 day adventure.

Craig Mod: Yeah, it’s the same thing with the Vipasana. I’ve had a lot of people ask me, can I just do three days? Can I do four days? And I’m sure Yuval would say you have to do two months to really get to the special place. But the 10 days, for example, in Vipasana, the 10 days, you spend the first two or three days struggling, angry, going through information withdrawal, smartphone withdrawal, frustrated, confused, and then it’s not until day 5, 6, 7 that you finally arrive.

And that you really start to get control over your attention and you start to have these really trippy moments where your body kind of breaks into particulate. It’s really trippy some of the places you get to, but you only get to those places on day seven, eight, and then by day nine you’re thinking about tomorrow’s the last day, and you start to be pulled out of the moment.

So in order to get to that two or three days of really special time you need. There’s an entry and an exit kind of tax. It was amazing the coming out of it, by the way. It was, I’m getting goosebumps actually now just thinking about the, how it felt to have made it through and then also looking around and seeing people who, there’s we, the group clearly was cleaved into two, one group got it, and embraced the experience.

Another group just sat in the frustrated state the entire time. And they just wanted to complain about, oh, the food wasn’t good enough. This wasn’t good enough. Or why they did this badly or this badly. Anyway, it was interesting to step back almost like a body and just be like, oh yeah, that’s the wrong path.

You’ve taken the wrong path. One guy, one guy who was, who annoyed everybody, he annoyed, everyone shaved his head in the field. There was, I did this in Kyoto and it was some. Very stinky man, young man. He was 22. VIPA is free, so you get a lot of, you can get these hippie folks. Anyway, he shaved his head in the field and then we were all, it was the last day he shaved his head in the field off, out of view of everyone.

And we’re having, we’re eating our final meal in the dining room. And we’re all, the joy was just so elevated. It was incredible. It was really special. And this Japanese guy comes in. And we’re eating and he walks over to the guy, the young guy who had shaved his head.

He was sitting in front of me and he had collected all of his hair and he just put it on his plate and you were just like, wow, man. People have really held in some crazy emotions. It was like the most violent thing I’d ever seen happen in my life. And we were all just, in this blissful shock.

Anyway, you need that and doing the kind of walks that I do, the, so for example, I’ve walked the Nao Tokio a few times, and what you’ll see is a lot of the people who walk the Tokio, it’s to, it’s from Tokyo to Kyoto. It’s about 600 kilometers or so. It can, slow. You can do it slow in a month.

What a lot of people do is they do it when they’re retired and they do it weekend by weekend. So two days, two days, two days, and they go and they leave and they go, come and they pick it up. And that I, that you fine do that if you want, but the real quality is doing it for a week or two weeks, or three weeks or four weeks, and then having this rigor that you commit to which for me is the, I’ll do 20, 30, 40 k of walking a day, and then I get to the end and I’ll do 3, 4, 5 hours of writing and photo editing every night.

And you just do that day after day and you don’t think you’re gonna be able to do it. And actually the last chapter in this book was written on the last day, the draft of it was written on the last day of the walk, the big walk I do in this book. And I got to the Inn, I think it was like a 40 5K day.

I got to the Inn, I was the hotel, I was just destroyed. And it was like 11:00 PM and I had to start writing at 11:00 PM And I just, okay, I’ve committed to this, I’m gonna do this. And it’s my favorite chapter in the book. And I don’t, it’s quite beautiful. I don’t think I could have gotten to that place without that commitment.

And also that, that weird relationship between using your body up completely during the day and then going to these kind of reserves to use the mind at the end of the day and then getting in bed at the end of all of that. And just feeling how much fullness can be rested from a single day. And that’s what I’ve learned probably the most outta doing these walks.

I’ve have hundreds now, hundreds of. These days of just extreme total fullness, like where the hand I was dealt in the morning, there couldn’t have been a richer way to play it. And to get in bed and feel that day after day is a pretty powerful thing. And then you’re able to, and like the Ana, in the same way you control your attention, you can bring that feeling of fullness back to a normal day and try to get a little, EA little more out.

But it’s hard to do that if you’re just doing a weekend and then going back to your real life and then going, doing another weekend of walking and then extracting yourself. So there’s something about that continuousness of it. And the continuous offline, this of it, which is also pretty critical.

So being dis disconnected from the teleportation that our smartphones are so good at. So forcing you to be present, forcing you to be bored. Sit with that boredom, sit with the physical pain of the boredom, and psychic pain as well.

Ross Andersen: We’ve got a moving mic somewhere there. It’s right there. Yeah. Any questions?

Raise your hand.

Speaker 4: So going on that theme that you were just talking about, are you able, or what is your practice for reflecting on back on those full days? So where I’m going with this is that since you’re doing them back to back, right? So if you’re doing ’em for 40 days, how do you think about, or how do you teleport back to day 20 or the experiences of day 18 at some point in your life?

Because otherwise it’s just. Those days are so rich and so full. What does that look like?

Craig Mod: And I think this is why it’s critical to do, to have this practice every night of writing and reviewing the photographs. And it’s gotten a little complicated. ‘cause now I’m shooting mostly film. So the photographic loop is a little longer.

It’s a little more extended, but that’s why you do the writing in that moment. Yeah, and I’m dictating for most of the day as I’m walking. I can’t. Stop myself from writing, essentially. So when I take away the teleportation, the social networks, the news, all these things that kinda take you outta the moment, my brain just fills that void with writing and just writing, thinking about things or reflecting on things, or if I have a conversation with someone, there’s almost this heightened super tastes or sense of like interestingness about what people are saying.

And so then I, you forget these things very quickly. Very quickly, if you’ve ever done field work or design ethnography, field work. I’ve done some research in Myanmar and I was out there, trying to basically see how they were gonna use smartphones. ‘cause they had just been given smartphones and farmers had just gotten smartphones and we were trying to figure out how can we, I was working with an NGO about disseminating farming techniques and information and education in real time through smartphones so they could get better yields, things like that.

And I was, I lived out there in Myanmar for, in the countryside for a month. And one of the things I learned, and this is why I think the popups I started doing this, and this was in 20 15, 20 16, I wrote a piece for The Atlantic about this. Actually, the Myanmar smartphone people, was that you learned anything you were observing in the field.

Get that down as fast as possible. You’re gonna lose it. If you wait till tomorrow, you’ve lost it. And so someone else asked me like, is this writing. Or this capturing desire at odds with being living in the moment. And I’d say it, it’s in conversation with it and it enhances it. And if I wasn’t doing the popups, I’m really glad I started doing them when I started doing the big walks because I wouldn’t be able to remember anything from these old walks and having that resource to go back to.

And now if you’re a member of my membership program, I, all of the pop-up archives are there. So you could go back and you could read the popup for this book actually, and then read the fine art edition and then read this edition if you want to be like really crazy about how do you get to this place with it.

But there’s five, I think there’s four or 500,000 words in that archive now. And without that I wouldn’t be able to revisit these things. So I have walks, I’ve done in Tokyo, I have walks, I’ve done in 10 cities around Japan. And the plan is to turn those into books. And by having that archive, I feel like I can go do that.

Gotcha. Yeah. Cool. Thank you.

Speaker 5: I’ve been reading a lot of haiku play and so I’m curious to what extent to you view your work as in competition? Hy and some extent looks to me like you have the owl sketches and you have images instead of pole, so

Craig Mod: Yeah. So like Maso ba is the. Grandfather of Haiku, and he was a famous walker.

He’s really who established this literary tradition of walking and writing and being in the moment. And his haikus are, like photographs in a way, these little moments. He wrote tens of thousands of them. And OK Mechi and the, actually the diary of his apprentice is something that John translated.

And so I have that as my archive in my archives as well. And I draw a lot of inspiration from their work. The days and the opening of OK Michi is really poetic. God, I wish I, this is something I should definitely have off memory, but if you search for the opening of the narrow road to the deep north, the first few sentences are so beautiful.

And this is hundreds of years ago, this guy setting this tone of how to do travel writing and how to think about, doing those sketches in real time. And I definitely draw on that I think in my work as well. Thanks.

Speaker 6: So obviously the Japanese don’t just accept, also embrace this idea of permanence and letting things go so that you can welcome Morgan and of. And I’m just curious if that’s something that’s slowly come in or something you embrace right away and how it’s changed you as an artist and as a explorer in water.

Craig Mod: Yeah, so one of the big examples of embracing impermanence is EZ Shrine, which is one of the most important shrines, if not the most important shrine in Japan. And it’s this really a shrine complex. There’s hundreds of sub shrines and but ES is famous because every 20 years they knock it down and rebuild it next to itself.

So it just keeps shifting 20 meters this way. Build the new one, keep the old one up. They sit side by side for six months and you can see they’re built out of, he nochi cedar and he nochi cedar kind of ages in this really beautiful way with a nice patina. And you can kinda see the old and the new next to each other for six months.

And and then they tear it down and then 20 years later they do the same thing. And they’ve been doing this for millennials. So there, there’s, it’s amazing, like the Colosseum has been there as the Cossum was. When the Romans were running around, but in maybe recently we figured out how to make the concrete.

I think that was something that you guys wrote about. We figured out Roman concrete finally. But that was like this mystery. We didn’t know how they made their concrete for thousands of years, whereas you say every 20 years you’re having three generations work together to rebuild. And so this carpentry, this knowledge is being passed down in real time.

And there’s something to me far more profound about being able to keep that going for 2000 years. Without losing the knowledge. So that’s interesting. That’s just interesting to feel and to not be like, how old is this building? How old is this church? How, you step back from that and you just think, okay, why this rock?

What’s special about this place? And you think more about power spots and energy actually. Koya Sun, is this also in the book? It’s this incredible, almost lotus configuration of mountain peaks and the co area is the, in the center of it. And that’s where Shingo and Buddhism established itself.

1200, 1200 years ago. Kuka, the head, head priest who established that, built that there and you, you go there and 1200 years ago to get to that spot would’ve been. Impossible. Just the, this peninsula is so cued and rich and wet and disgusting, and the leeches like the mountains are not friendly and the boars and the bears and everything.

You really have to want to get to that spot and to think about them doing this work, to build this incredible infrastructure and the cemetery up there is just unbelievable. And to walk, to go up there and walk through it. You realize why they picked that spot. You just feel that, and I think Japan has made me sensitive to that in ways that maybe Western classics and things like that didn’t.

Speaker 6: How have your rules for walking changed? That you’ve discarded as not being as helpful for the meditative aspect.

Craig Mod: So my main rules have stayed the same. And I started building up the no internet rule about 15, 16 years ago. I wrote something for a magazine, a publication called The Manual.

And that was about, and this would’ve been 2010, and it was about turning the internet off when you go to bed. So around like 10:00 PM turn the internet off and don’t turn it back on until after lunch. And I wrote about how that felt so radical in 2010 and how lunch would, the mornings would be so quiet.

And that was when I was able to do what I felt was real work and real focused work. And then lunch would roll around and I could feel like my brain was a gold. Like a bowl of goldfish and the guppies and do, they’re just waiting for the dopamine to be dropped down from Twitter and, whatever.

And tech meme and hacker news or whatever the heck I was reading. And and I think understanding that the power of that helped me get quickly to the no internet, no social media, no news on the walks. And the first walk I did, I actually had no real time feedback. I built this SMS system. So instead of using email.

I built this weird, complicated, expensive, it was because you have to pay to send SMSs system where you could subscribe. And then every day at the end of the day, I’d send you a little SMS and a photo and you could reply. And I didn’t see any of the responses. They were all put in a database that was hidden from me.

And so I’m walking blind. I don’t know how many people are subscribed to it. I don’t know how many people are responding to any of this stuff. And at the end, I hired a designer and I just had my friend send him the database and I said, okay, lay out a book. Here’s my little things I sent. Here’s my photos.

Lay out a book with all the responses in, and have that we’ll print one copy a blurb book. It’ll be waiting for me when I get home from the walk. And we did that. And that project, which was six years ago, right about now, is what set in motion everything else with the book stuff.

Because I got home and this beautiful book was waiting for me and I opened it up and it was hundreds of pages of long and it was just thousands of these responses. And because I told everyone I was gonna see, I wasn’t gonna see it in real time. And because I told everyone it was gonna be anonymous, I wasn’t gonna who.

So the con, the confession quality of Yeah. These notes was really astounding. Yeah. And but things like, my mother died yesterday and reading, following along and knowing where you are. Whatever was powerful to me this morning. Things like that, it wasn’t like people admitting to murder or anything like that, but it was this other level of kind of profundity that giving these people and saying, look, this isn’t gonna be a real time conversation.

I think unlocked a kind of intimacy, paradoxically, this kind of intimacy that you don’t get in real time on Twitter, Instagram, and things like that. So experiments like that, playing around with publishing, like that just made me think more and more about the power of those rules. And so then establishing.

No, no news, no SNS what are my other rules? The other big rules. Everything is planned in advance. So I’m not doing any logistics on the fly because. Logistics take up a tremendous amount of brain space. If you have to think about where am I gonna stay tomorrow?

A lot of these places I’m going to have only one place to stay anyway. And so if you don’t book it, you’re not gonna get it. I just want it to be, I have spreadsheets of where I’m gonna stay, if they’re gonna provide me with food or not if they have laundry or not. I know the kilometers I’m gonna walk each day.

I have that all set up so then I don’t have to think for one second about that and I can just be fully present. The fundamental rules of being offline. The portrait rule, I am a little bit flexible on, and I’ve done other things where I’ve recorded binaural audio every morning at 9 45 or 10 in the morning and done that, or I’ve done video.

I’m flexible with where you can play with ’em. But the fundamental rules of creating this sort of boring space for creativity to flourishing, hopefully, ideally, and again, like you don’t know if you’re gonna meet anyone interesting on the road, you don’t know if anyone interesting is gonna be out there, but having now done this.

Hundreds of times, day after day, you realize the, if you don’t find something interesting, that’s the onus is on you, that’s you failed. It wasn’t the universe not providing you with something interesting. ‘cause there’s always something weird out there, no matter how boring you might think it might be.

Speaker 6: Just reflecting on that, what is it like when you’re not walking? So is there a balance and what kind of structure does that look like?

Craig Mod: Right now, it’s just chaos, right? It’s is total chaos. I see this tour, it’s, I’m on the road for six weeks, which is a long time to do something.

And this stuff, this is a lot of energy to do. If I normally do one of these events, I need three weeks to recover. So to like slam ’em all together. It’s a different kind of aesthetic practice, but I see this trip as drawing on the walking practice of trying to figure it out and draw from different energy reserves.

But I, I found that I just am better at clumping work into chunks and saying, okay, these months are for this project. This is for this project. And then when I’m not in that space, I’m okay with being more flexible. But, these walks fundamentally are. Self-imposed deadlines slash forcing functions to get me to write.

All throughout my twenties, I struggled with alcohol was a thing I kept turning to because I didn’t know where to turn. And then I really wanted to be more prolific and I wanted to write more. I wanted to work on bigger projects. I didn’t know how to, and I think a lot of people struggle with that.

And just the fact that when I launched my membership program, I had this. A group of people who stood up were giving me money and essentially permission to go do big walks like this, that, that changed the formality of it in this strange, really important way where I felt I had a sort of ethical duty to, to, to show up, to really be there, even though no one would’ve cared.

No one was holding me to account at all, but just having those people out there, seeing that money come in. Having it be funded by this anonymous group of supporters anonymous to me in the sense of just there, there are so many people out there. That was critical to believing that I could abide by the deadlines and that I could do the walks, and that I could push through the walks and that, my feet are bleeding, my shoulders are bleeding, and I find a way to get past that and figure out how to wear the pack better, figure out how to tape my feet better.

All of those things came out of. Those deadlines and that support and drawing from that permission. And so when I’m not in the walks, I try to be gentle with myself and, okay I’m okay if I don’t, I’m not as prolific as I am on the walks. My goal isn’t every 30 days to write 50,000 words or 60,000 words.

But there is something nice about setting those deadlines and hitting those deadlines. It’s like Jerry Seinfeld and all these, all these sort of super prolific people. They have the thing where they cross it off. They cross it off every day. I’m gonna, I’m gonna do this thing, I’m gonna do this thing.

And there’s something powerful about that. So I try to just take as much of that. As is gentle to my soul back from the walk and and when I feel like I’m getting weak or I feel like I’m losing my edge, it’s time to set up another giant walk and go out and do it. And this is kind of part of that.

And also next week, I have a new fine art book coming out on Monday, which is insane to do during this. I’m messaging with my distributor and trying to set up, get stock set and make sure shipments are in place. But I went and I shot for 10 days on the Peninsula in February because I was so worried about what I’m doing now, which I don’t see.

I see. This is a, this is important and interesting and this I’m learning. I’m gonna learn a lot on this tour, I’m sure. And to go out and be able to talk about this is an honor and it’s amazing that everyone has come out. But at the same time, I know this isn’t the work. The work is the work. And so I got really paranoid at the beginning of the year.

I just thought, oh my God, am I gonna be doing any work? Work? And I just shoved a crowbar this 10 day photographic odyssey into my schedule. And I called all these, all the people in the, in this book essentially, and said I wanna come and photograph people. Can you introduce me to, divers and truck drivers?

And everyone was, delighted. They couldn’t wait. Please come. We’ll introduce you to everyone. I went down there and I did these days where I was getting up at 4:00 AM photographing all day and doing it all on film, not knowing if I was really getting everything and just ringing myself dry.

And I, and actually I cheated. I rented a car and it was just, it was quite nice to have the car and the cover all that ground, but I kinda went through, did all that, and then laid out the book in March. Sequenced in March, and then we went to press in April and it just arrived literally yesterday at the warehouse.

And I’m gonna announce it on Monday. But that was critical for me to do that, to stay sharp, to feel like I was staying sharp because I am just in this state of total paranoia that I’m gonna lose the edge, that you get, the gift that you get from the walk. And and so I’m constantly balancing that out, but also not beating myself up too much about it.

Speaker 6: Yeah. You mentioned that you take the pictures of film. I’m just wondering if you’ve ever felt a draw to digital photography or if there’s a reason why you stayed

Craig Mod: with film. I, so I started on film 25 years ago. When I got to Tokyo and then I had a dark room in my apartment. I was, developing, I was totally fully committed.

And then digital got really good, DSLRs got really good in the mid to late two thousands, and I just shifted to that. And then I saw film as being a hindrance to creativity because it was overcomplicating things. And I, I just wanna get to the photos, I want to edit, I wanna sequence that’s, that to me is the work.

And so from basically 2000 7, 0 8, 2 thou, probably 2004, five actually, to. Two years ago, I didn’t touch film at all, and it was only digital. And I was shooting like a queue, like M 10, M 11, and it’s great, beautiful, incredible. But two years ago, I had this weird moment where I, my hassle Blad was sitting on the counter.

It’s this beautiful object. I’d sold all of my old film cameras. I, it kills me. It was so stupid. I did this seven years ago. I was in this minimalist I gotta get rid of everything. I’m not touching, not using. Mode and I sold them all for a song. It was just, it’s heartbreaking to think about it.

All these cameras I used in my early twenties are now in some, hopefully someone’s using ’em, they’re in used camera shop. And I pulled the, has blad off the counter and I thought, okay, let me throw a roll through this. It was inspired by, by someone in my life and I took it out and it’s.

Clunky crazy thing, has bla the square box and you open it and it like snaps open and you take it out. And I took it out and I went to some cafes and I was like, Hey, can I take your photo? And just, everyone changed the energy of everyone when you take this thing out, you open it up, it’s real.

And they’re like, is that you’re shooting on film? Oh my God, this is a serious thing. It’s everyone stiff into a certain degree, but then also performed a little better. And I got those photos back and I was like, Ooh, this was fun. And then I took it on a 300 kilometer walk across England.

That was the only camera I brought was this has blad. I put it on a peak design shoulder strap, snappy thing. And so I had this giant medium format camera on my pack. I looked insane. All these British people were just giving me side eye. And and I shot with that in the cowa, not the co walls, but the lake district and up there I walked Wayne Wright’s path.

And I got those photos back and I was like, holy crap, this is fun. And I like the delay. And so as soon as I got back to Tokyo, I was like, but this thing’s too big. I bought an M six I went straight to the used camera shop, grabbed an M six and haven’t turned back since then. And so the new book that’s coming out on Monday called Other Thing, which is a, this, there’s so much complexity around this book, this peninsula for me.

There’s the popup newsletter, there’s my fine art edition, there’s the Random House edition. Now there’s this photograph only. Addition responding to this edition, it’s in full color, that was shot with a Maia seven two, like a M six and a like a mp, and that was great to do that. And the thing I’ve taken away, the real thing about film that you can’t deny, ‘cause there’s a lot of woo, but you can’t deny getting the negative, which is this physical, immutable thing.

Also it’s plastic. It’ll probably last a thousand years. It just doesn’t, it doesn’t go away. And having, and now my life as a photographer is split into these two worlds of everything I shot before 2022 digitally. And now I have this archive, this corpus of negatives that’s building up. And I’m heartbroken that I didn’t start earlier.

So it’s been an interesting emotional journey, but it’s fun.

Ross Andersen: All right. I think we are over time and Craig has some books to sign, I hope. Yeah, I’m getting the yes. Okay. Where is he gonna set up? What’s the timing? Oh, there’s the table right over there. All right, give it Craig. Craig on a big hand.

Thank you.