Episode 2

Notion — Tribecca — Rob Giampietro

Craig Mod in conversation with Rob Giampietro at Notion in Tribecca, chatting for fifty-three minutes on May 04, 2025

Rob Giampietro — Rome Prize winner, MacDowell fellow and all around design mensch — and Craig discuss his new book 'Things Become Other Things,' his walking journeys across Japan, and his unique approach to publishing and community building. Supported by the gradual evolution of his walks into a literary and photographic endeavor, Craig discloses how his solo treks and companionship with mentors like John McBride have shaped his narrative style. He also delves into his innovative 'SPECIAL PROJECTS' membership program that funds his creative pursuits and offers a personal reflection on the transformative experiences of walking and connecting with people in varied landscapes. The conversation wraps up on the note of Craig's experimentation with bespoke digital spaces that foster community engagement beyond conventional platforms.

Guest Links

Chapters

- 00:00 — Introduction and Welcome

- 00:15 — Craig Mod's Background and Friendship with Ross

- 02:23 — Craig's Walking Adventures in Japan

- 04:02 — The Evolution of the Book

- 05:48 — Reflecting on Childhood and Bryan

- 08:57 — Walking Rules and Daily Structure

- 09:58 — Capturing Stories and Voices

- 12:13 — Impact of COVID

- 15:57 — Unexpected Fame in Japan

- 23:51 — Group Walks and Mentorship

- 28:06 — The Influence of John McBride on Walking and Art

- 28:56 — SPECIAL PROJECTS Membership Program

- 30:55 — The Birth of CraigStarter and Its Success

- 33:18 — Navigating the Publishing World and Creative Independence

- 40:01 — The Power of Walking and Mentorship

- 44:39 — Future Walking Plans and Creative Projects

- 48:53 — Closing Thoughts and Reflections

Subscribe to the Podcast

Transcript

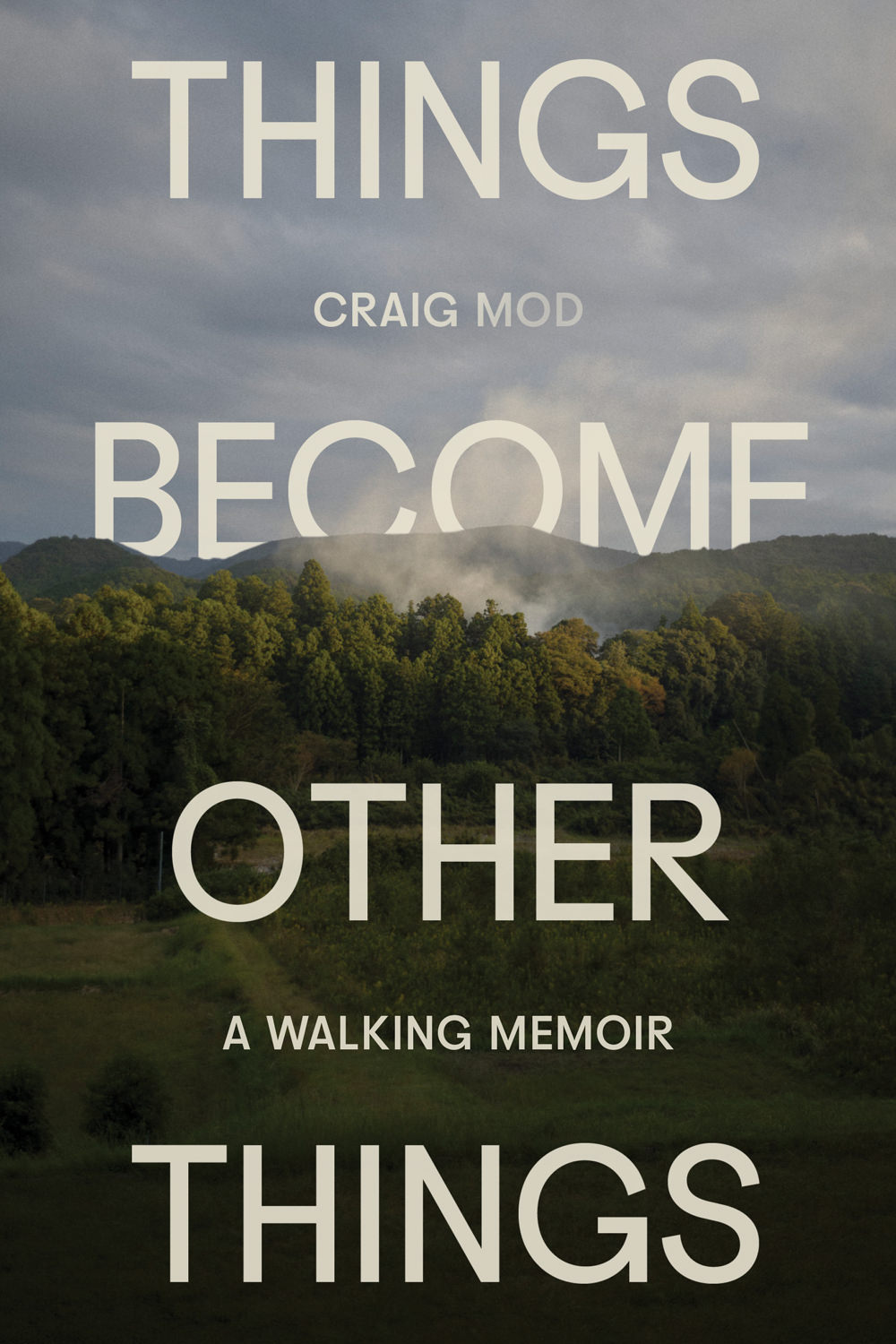

Rob Giampietro: Okay. Hi everybody. All right, we’re about to get started. Welcome, welcome to our wonderful author Craig Ma. Very excited to have him here on the week of his, the publication of his new book. Things Become Other Things which we’re gonna talk a little bit about. But I just wanna introduce Craig briefly.

I, there’s a saying I love that books Make Friends. And that is certainly true for Craig and I. We’ve known each other for 23 years. We met. Through his first book, ku, which was published in 2002 and was admired by my former boss, bill Ell because it had the same printer that we were using.

Then we finally met in person in 2005 and we were jurors for the Art Directors Club Awards. And that led to a whole bunch of things that we’ve done over the years, like writer retreat with our friend Frank Ro. We also organized a conference in Tokyo together. And after that we got to do. A walk and talk that involved a lot of the places that he writes about in this book.

So I, it was fun to not just read about them, but also get to experience ’em. Craig is a music fan design and product guru, a community builder, and many more things. But above all, I think a storyteller. If you dive into his newsletters, rodent and ridgeline, you’re liable to find, book reviews, camera recommendations, all kinds of meditations on the future of publishing and dispatches from his incredible long walks in Japan.

And he’s got some great notion connections too, including the wonderful Rafael Shad who would be here if he was not on paternity leave with his new baby. But they’re old friends as well. Over the last month I’ve been really delighted to be able to dive into this new book, which we have some copies of here.

Definitely let Brittany know if you would like one. But now we’re gonna chat a little bit about it. Welcome, Craig.

Sounds good. Thank you for having me.

Yeah, so I think maybe just to start, and for those who aren’t as familiar with the book. Wanted to orient. This book brings a lot of different styles of book together.

There’s like a viewbook, there’s a guidebook, there’s a guidebook aspect to it. It’s like also a book of letters, sort of letters to your friend Brian, letters from John to you who’s the mentor, a mentor of yours, and someone who’s guiding you on your walks. There’s a quest aspect to it.

There’s a journalistic aspect to it, it’s a memoir, so it’s like many things together. And it also has this really wonderful experimental quality. It’s very like dreamlike in parts and associated. So could you talk a little bit about how it developed and how it came together and a little bit like also what the editing process was like?

Yeah probably the easiest way to explain a lot of what I do is I do these giant walks across Japan, through Japan, and I’ve been doing those for about. 10, 11 years now. I’ve lived in Japan since 2000 and I’ve had a couple of little one year, two year stints outside. But for the most part I’ve been in Japan since 2000.

So this is my 25th anniversary this year, which is pretty bizarre. So I’ve spent more than half my life in Japan. And and about 12 years ago I started doing these walks. And so I’ve walked Tokyo to Kyoto three times and that takes about, if you do it slowly, it’s a month Last year, right about, actually at this moment, I was in the middle of the walk.

I did it at the rate that they did it. In the 17 hundreds. I wanted to see what that felt like. And so they were doing 40 KA day, so I did it in 16 days. That was not fun. It was pretty painful. 40 KA day. I was carrying three cameras and I’m interviewing people and as I’m doing these walks, I’m talking to everyone I see along the way.

I have a whole set of rules we can talk about later maybe if you want. Yeah, totally. And I’m just collecting, photographing, collecting stories, essentially looking for archetypes of ways of living. That’s what I’ve realized. Is the main goal of what I’m collecting. Like how to, what are the different shapes of life that you can have and what are the good lives that you can live out in the world?

And, seeing all the different shapes of that. And then putting that together. In a lot of the walks I’d run what are called popup newsletters. So it’s a newsletter that starts and ends with the walk. You can, you opt into it, and then every night I send you a newsletter about the day. And so I’ll do eight hours of walking and then I’ll do 3, 4, 5 hours of writing and photo editing every night and send that out.

And by the end of the walk I’ll have. 30, 40, 50,000 words, which is essentially like a book. So this book started four years ago, pretty much on today, May 10th, 2021 is when I started that walk. And I did that walk for about 30 days, sent out a bunch of newsletters, and then I thought, oh, I’m gonna edit the newsletters into a book in three weeks.

That was kinda my plan. And then it ended up taking four years. But that was the. The broad strokes of it to turn this into a book.

Yeah. And I mean it’s, I was the recipient of many of those newsletters and it’s really fun to be able to follow you on your journey. But it’s also really interesting to see how this book evolved from newsletters to your readers, to your newsletter subscribers, into really like a set of letters to your friend Brian who is someone who was part of your childhood.

And, helps you compare the experience you’re having on the walk a little bit to the experience of growing up. Do you wanna maybe talk a little bit about him and about that kind of process of comparison?

Yeah. So when you’re doing the pop-up newsletters, you’re writing in real time and the deadline I find to be really generative and important.

When I’m doing the walks after eight, eight hours, 20, 30, 40 k of walking, you’re really tired. Last thing you wanna do is. Three or four hours of writing. But it turns out you can do it. And not only can you do it, but being in that kind of slightly exhausted physical state and then really, creating this covenant or whatever this like this promise to yourself that you’re gonna do this other work and then doing it, you get to go to really interesting, weird, creative places, but at the same time, you’re holding back a little because it is.

Essentially first drafts real time. So when I was on the walk four years ago, I wasn’t writing about Brian, but I was thinking about Brian a lot, and Brian was basically a kid I grew up with. And we met in first grade. We’re best friends in elementary school, that sort of thing. And I’m adopted. I’m an only child.

So this idea of having a brother, pretty powerful. And so he was essentially my brother, he had two older sisters, but the town we grew up in was a, at that point, early eighties entering post-industrial. Reaganomics gutting a lot of stuff in America. My town was an airplane engine factory town across the river was the cult factory for putting together guns.

And there was like Coca-Cola bottling factory, so it was very blue collar, kind of salt of the earthy town. And people were, struggling. There was difficulty with jobs. There was a lot of violence. There was gang stuff happening. There’s this kind of ambient sense of violence throughout our childhood and.

Brian and I were best friends all through elementary school, and then we tested differently. I tested a little better and that put me on a different path inside whatever the system of that, of our town. And we graduated high school and basically a week sort of spoiler, but you get a sense of it.

Early on in the book, a week after he graduated, he was murdered with another kid. This was not a huge surprise in my town. So the last, that was almost 30 years ago. And the last 25 years I’d spent carrying a kind of a weird guilt. Could I have helped him? Could I have averted this?

‘cause we were side by side all through elementary school and then getting split and you just realize how little control you have over how the system pushes you. And it was after doing the pop-up newsletter and then re and then revisiting the popup and rewriting it and going back through thinking about what the book could be that Brian started to pop up.

Because as I’m walking this peninsula. I’m walking this area south of Kyoto and it’s also industrial. Very blue collar, socioeconomically, really aligned with where it came from, and yet the violence isn’t there. There’s a systemic support you feel. Obviously in healthcare, all these like fundamental social safety net things are in place so people don’t fall as far, you can’t fall as far and as I’m walking and I’m seeing little kids run around, you just think what would it have been like if we grew up here?

It’s inevitable. And that kind of just more and more got pulled outta me. And then it felt like maybe finally this is all happening during the height of COVID. So there’s a silence to the world and kind of a solitude. And it just felt like maybe this is the time to revisit the thing with Brian, that friendship, and think about it in the context of, how my life has gone over the last 25 years since he was murdered.

Yeah. And really you start with catching him up on your, the last few years of your life and how you’ve integrated into Japan, how you’ve really become adopted Japan in a sense, and Japan has adopted you and I think the kind of the warmth and the kindliness of people that you meet there.

A lot of your encounters throughout the book are with strangers in cafes, strangers on the road. I think you have a rule of that you need to meet someone before 10:00 AM or photograph someone before. Do you wanna talk a little bit about, the structure of your day going

up? Yeah, so the rules of the walks are essentially no teleporting, so no news, no social media, no podcasts, no music.

The goal is to be just there in the walk and also really bored. It makes you really bored. Like you, we forget. What boredom feels like, every, literally half a second of free time we have, we reach for the phone, we start pulling, look, pull the refresh, try to get more dopamine, all this stuff, and we take that away.

It’s radical how much of a void. Is left in your brain getting rid of the smartphone. And so part of that is, is just what fills that void. And for me, writing fills that void. As I’m walking, I’m just writing, writing, I can’t stop my brain’s just already writing sentences, writing paragraphs, what are we, so I’m dictating a lot into AirPods and you can kind use a a shortcuts script to a pen, to a note so you don’t have to touch the phone.

So you can be like, I

use this too. It’s actually fantastic. Yeah,

It’s pretty cool. And. Transcription’s. Okay. But it works well enough. So I’m transcribing as I walk, and then I’m meeting people and then snippets of conversation come in and I’m trying to really grab all of this especially because a lot of people I’m meeting are elderly.

A lot of these areas are depopulating. Japan has a, the birth rate right now is 1.2. I think, it’s one of the lowest in the world. South Korea’s 0.7. Gideon Lewis Kraus just wrote a big piece for the New Yorker about. The lack of children in South Korea it’s pretty amazing.

It’s scary. We’re all trending in that direction and so a lot of the Japanese countryside, depopulating, there aren’t that many kids. And then you talk to the elderly people who are running these shops and you realize that in 10 years almost everything I’m walking through will be gone.

So these old cafes, these old Tami makers, a lot of the villages, it’s. In 10, 15 years gone. So there, there is this kind of anthropological component of we have to grab this as quickly as possible and I’m trying to photograph and get these conversations and there is, for me in the book, I trans translate and transcribe this countryside vernacular Japanese to North Carolinian English.

That’s in my mind what, it’s almost like Appalachian English. And so that’s a part of how I’m transcribing in the book as well.

Yeah, all the voices are so incredible. The voices of some of the people you meet. And I also think it’s interesting the role that the landscape plays in the book as well.

As you’re walking through the landscape, you’re capturing these incredible encounters almost like August Sonder or WG Zeal. Like you’re finding these finding these people and using them to remember experiences in your own life or capture them as reactions. The landscape is also incredible.

There’s a kind of opening section about a typhoon that then you learn more about later in the book. And it, I think the way I interpreted it anyway was like, it’s this thing that tosses all these pieces up into the air and then they land in different configuration and that’s a little bit the fragments of the book and the fragments of the memories and the way they come back together and the connections that you make back with them.

I also think there’s COVID going on in a lot of the book and you as a foreigner and wearing a mask or trying to, adhere to protocols that are maybe different from the ones you were thinking of or expecting. So I maybe just talk a little bit about like the role of the environment in the book too.

‘cause I think it’s really interesting.

Yeah. I mean it was Haida COVID and yet Japan still only had a couple hundred cases. I mean it was like, in this area I was walking in Mier prefix. Sure. And WI, a pre fixture were, six cases, something like that. But everyone was being very careful and I was, testing and being very careful as well.

And but a lot of the shops would’ve signs on them saying, we don’t accept out of pre fixture customers. And so I would, I’d, been walking for several weeks. I’m like, when do I become. In group person, and I would open the door and be like, is it okay if I could? And no one really cared.

But it was more about truck drivers. The Peninsula has a lot of truck drivers coming through, and I think they just didn’t want these sort of transient work related people who might be going to bars or something at night. Then coming to these little cafes for lunch and transmitting COVID. That’s what they’re mainly worried about.

But the. To get back to the earlier point about not having social media, not con not being online, not looking at the news, cre, creating that void, allows me to, I think, connect with these people in a way that I wouldn’t otherwise. Because you are so bored and you’re so desperate to connect to someone or something.

So you’re more I’m more primed to talk to people I wouldn’t talk to normally. It’s real easy when you have your phone to just go into a place, hide in the corner and just be in your phone. But when you don’t have that and you’re just sitting there.

Audience: Naturally,

Craig Mod: people start talking to you or I find myself so desperate for stimulation that I wanna know the story more, and it’s this weird catalyst.

It really does get me to be more social, to be more extroverted, just by having that off in a way. And then you come you get to the end at the end of the day and you’ve collected out of this day where you’ve planned nothing. The only thing I plan for my walks is where I start and where I end.

And I do this all before I leave because I don’t wanna think about this on the road. I just wanna be fully present and just focused on the photography and the storytelling. I don’t wanna think about where am I gonna eat, where am I gonna stay? None of that stuff. And you get to the end at the end of the day and you realize you just have this wealth of experience that you couldn’t have planned for, you didn’t expect.

And then you can write 2, 3, 4, 5,000 words and you get into bed and you just, you feel like the cards that you were dealt in the morning. You couldn’t have played a fuller hand. That’s the experience I started feeling. That’s what got me addicted to doing this. More and more long walks and you do that day after day and you have this kind of physical rigor and then this creative rigor at night and you just ring as so much out of a single day.

And that becomes an archetype of what’s possible and you can carry that back to your normal day-to-day life. And when I’m back at home. I don’t talk to that many people, and yet I think, I’ll be walking around Tokyo and I’ll be like, it’s crazy. I, all these folks, I could be stopping, I could be, having a conversation with, I’m like, why don’t I, why don’t I feel like that same sort of impetus or catalyst on my day to day, life?

And I think we do close ourselves off. And I think being overly connected online, touching the phone too much, closes us off as well. And so having that, knowing I’ve not had hundreds of days where I’ve just had this total fullness. And being able to tap into that when I need to is, it feels a little bit like a superpower.

And

one of the genres I didn’t mention is reporting or reportage and obviously that collection of stories, that hunger for stories, even stories of everyday life is something that really drives you. I know. But also you’ve done some really interesting reportage outside of kind of this book.

You’ve written about pizza in Japan. You’ve written about tourism in Japan for the New York Times. Do you wanna talk a little bit about how those experiments and writings also figure into this type of text? Yeah. I started doing, or your practice maybe more generally.

Yeah. Yeah. I started doing these long linear walks. So it would be, no trains, no bikes, no car, nothing, just what you have to walk the whole time. And I thought, okay, this is interesting, but does it always have to be linear? And I started thinking about all these kind of flyover towns, like towns that you would.

Take the sheen to go to Kyoto and you’d stop at three or four stations along the way, but you’d never get off. And I just started thinking what if I went to these weird little midsize cities that no one really goes to? And so I set up a walk through 10 mid-size cities where I’d spend three nights, four days in city, and I’d have to walk, I’d have to walk 50 K in each city.

And the idea being like if you force yourself to walk 50 kilometers and like a mid-size city, you’re gonna touch most. It, and you’re gonna meet a lot of people. They would meet, and you’re gonna go down, you’re gonna be looking for little roads and alleys. And I did that and I went to Ate and Hodo moca, akata, Matsumoto, Suga, Amichi Matama, karasu Yamaguchi and Kago.

And in doing that. There were a couple cities where I was like, why? This city’s amazing. Why has no one ever in 23 years, this is a few years ago now. Why has no one in 23 years ever told me to come to the city or told me about the city? And so one of the cities was Mor Yoka and the New York Times, I’ve been writing little pieces for them, freelance.

And three years ago they came to me and they said, Hey, we’re doing our 52 places to visit. They do these lists every year. You just had the 20th anniversary today this year. And, and they said, Hey, do you wanna submit something? And I thought, yeah, like I, I’ve been to these 10 cities, the city, Mor dca.

It was pretty cool. Great independent shops, cafes, music stores, music clubs, jazz clubs just this incredible richness. And some I don’t wanna, I don’t wanna make it sound overly. It’s simplified, but there’s a, just a richness and simplicity of life,

like an essential quality.

I think there’s

an essential quality. There you go. Rob’s very good with words. Essential quality. That’s what I got

from your writing.

Essential. But there’s an essential quality of life and I pitched it pretty hard to the times and you just write this 200 word little pitch and they don’t tell you if it’s gonna be in the list or not.

They don’t tell you where it’s gonna be. And then the list comes out. And number one of that year was London. And then number two was more yoka. And Japan. Just freaked out. Like they were just like, what

number one? That’d be, it’d be like you were like a lo-fi celebrity in Japan before that. But I think I was, I think that was when things changed.

I was not on, no, I was not on the radar of Japanese people. All of my writing has been in English and most of the stuff I’ve done has been in English, and that came out. It would be like Hoboken, it’d be like saying Barcelona is the number one place to go to this year. And then number two is hobo I, or like number two is, a random city in Alabama.

It’s just very bizarre. And they found out that I could speak Japanese and then suddenly it was this avalanche of media. People just coming to my house, coming to hotel rooms. It was bananas and it culminated last year in the most famous TV personality in Japan, this guy Tom Modi’s son who wears sunglasses, his team reached out and they wanted to do a TV show.

And it was, I didn’t know who this guy was. I don’t have tv. And before that the mayor, the article came out and, the mayor reached out and I was like, okay, I’ll go meet the mayor. And I go up to meet the mayor and I think this is gonna be a very casual meeting in a back room with the mayor.

And they leave me to the mayor’s office and then they go, okay, Mosan, here we go. They opened the doors and they had invited like every TV station in the country. It was just a wall of cameras. Rapid fire, paparazzi, like DSLRs, it just flashes going. It was so bizarre. I go in, I meet the mayor, we sh, I shake his hand, he goes, thank you for recommending us.

And he goes, good luck. And he leaves. And I hadn’t prepared anything. I haven’t prepared a speech. I, and I’m in front of all of these journalists and they open I make up the speech on the spot. I’m like, know. Thank you. I’m honored that you guys are happy about this. I hope it doesn’t cause too many problems.

I’m thinking of, over tourism issues. I’m actually quite nervous and, I feel vulnerable in the sense that I put these people on the map. And the reason I agreed to do a lot of the media was because I wanted to help them understand why I feel. There’s a good quality about their city, which can be hard to see for yourself, but also to get the most value out of this as possible for them to really bring the most value out of this.

And the, it’s opened up to questions. And the first question is, the guy, a guy comes up and he goes, Mosan thank you for recommending us. How do we solve poverty? And I was like, I, you’ve got the wrong guy. I just think you have awesome cafes. I like your coffee.

I don’t know how to solve poverty. I’ve just, I’m just some ding dong who walks and I pointed at your city. That’s all I’ve done. So it was a very ego, try to be egoless as possible. And this Tam thing, this celebrity guy who reached out and wanted to do a walk with me. In the city. I also, I didn’t really wanna do this, it was a pain, but one of the guys in the city reached out to me and said, Hey, he won’t do it unless you come.

And it would mean a lot to us. And so I went up there to do this thing, to do this TV show, this two day shoot, we got this crew of 40 people, there’s six cameras on us. It was like the

opposite of your normal walk situation. You’ve got like a roving camera crew.

It was bananas, he’s kept in like a vault in a van.

He’s 80 years old. He’s literally been on TV every day for the last 50 years. He’s there’s not one person in Japan doesn’t know this guy. He wears sunglasses. He lost vision one of his eyes when he was a kid. And so he always has sunglasses on. He’s this comedian, but he is also, versed in history.

He is considered a really intelligent comedian and, and they’re like, you stand here and then there’s another announcer who’s kinda helping us. You stand there and then they’re like, all right, call out Tom Modi. And he comes out of this van, he’s he’s four feet tall. He is a really tiny guy, and he stands next to me and there’s there’s no introduction at all, and the camera guy goes, all right, action.

It was like lost in translation. And I was just like, what the

Audience: fuck?

Craig Mod: What am we gonna do? And Tam Modi goes, I’m Tom Moori. And then the girl, woman next to him goes, I’m Morsa. And I just go, ah. And I grabbed Tom Modi and I start shaking him. And I’m just like, I, dude, we gotta say hello before we start this.

I don’t know what I’m doing. And like the camera crew just looked mortified. Three guys killed themselves. Like it was, I don’t think anyone’s touched to MOA in 50 years of him doing tv. And and it went fine after that, but it was, it was so stressful. You broke the ice. I broke the ice, and then walking through town with him was insane.

I’ve never felt. Celebrity at this scale. Before it was like beams of love coming off every single person. People were, construction workers were screaming downtown Sun, everyone’s like old ladies were hopping up and down. We went to the morning market. There were a few hundred people in the morning market.

It was like Moses partying the Red Sea. It was just. Unreal. 80-year-old women crying. Oh my God, it’s dumb boy. And then people coming up to me going, thank you all aside for bringing him to town. It’s, it was goosebumps walking next to this guy and just feeling that bizarre adulation, and, but, and feeling how much it meant to the city to have him there.

And so it was cool to be able to do that. And then I could slink away and just, and disappear.

I guess maybe, I think that’s a good moment to this older man to talk about models or mentors or kind of figures in the book. One of those is John who helps get you started with walking in Japan.

Maybe different, but Kevin Kelly is someone that you’ve walked in groups with and I know that’s a different format and maybe something that would be great for you to talk about too. ‘cause I think not every, not everybody wants to. Walk alone, although some people may. But but maybe just to talk about those two figures and maybe contrast the two, the solitary versus the group setting.

Yeah, the me walking alone is weird. It’s definitely weird to go for 40 day walk alone. It’s weird and, I see it now as a response to the violence of the town. I think what happened to my friend Brian. Getting murdered and me feeling like I had to move across the country and kind of create To be safe.

Yeah. To be safe to, because the first thing I felt when I got to Tokyo was how taking care of everyone was. And I think that, not consciously, but almost ambiently, subconsciously, I felt, oh, this is a place where people are to be are taken care of. And that was shocking to me. And that’s part of what kept me there, throughout my twenties.

And and these walks, these solo walks too, I think are also a response to all of that and trying to process it and find a way to transmute it into something interesting and find meaning, why am I living there? Why is this, why have I created a home in this place? And all that stuff. But I’ve also done these walks with other people and Kevin Kelly, co-founder of Wire, written a bunch of interesting books, kinda a, a techno optimist.

And I met 15 years ago, actually in New York at an event. O’Reilly Media event and we started doing walks together and then we had so much fun doing walks together. We started doing these things called Walk and talk. So we’ll invite six or seven other people and we’ve done eight or nine of ’em now in Bali, Thailand.

We just walked in Spain two months ago, COWA England. And we walk for about 20 KA day. We’ll do this for six days, and then we have seven dinners. And every dinner is a Jeffersonian dinner where you sit around the same table. It’s one conversation, one topic, and we talk for about three hours and kind of everyone participates in, one conversation.

And these walks have become some of the most profound weeks of my life, being able to spend time with these incredible archetypes of people. And Kevin himself being an amazing archetype as a father, as a creator, as someone who knows enough. I think there’s a there’s an issue in Silicon Valley that you can see where people don’t know where their lines are of enough, what you know, when am I full?

And you see a lot of folks go off the rails, especially as they become richer and richer. I think Kevin is one of these people who had the opportunity to become. Far richer than he is, and he is doing fine, but far richer than he is because he knew where all these enough lines were, and he knew what to focus on, what was fulfilling for him.

And so to feel that from this guy, he’s 73 now. And to be able to spend all this time together and then invite these people, we love artists, writers, photographers, actors we had a really interesting actor, neuroscientists, these really incredible people to spend a week with them. And you’d spend all day talking.

It’s like adult bootcamp in a weird way. And you come away, people are crying. It’s very emotional. But to have those kinds of weeks as you, the polar opposite of my solo walks, and there’s a richness to my solo walks where I can meet people in a way that I can’t when I have even one other person with me.

And I, I can think, and I can photograph, I can only photograph when I’m alone. I can’t, if we’re in a group photograph, I can’t get into that mind space. And so it’s good to have these, it feels like a good balance. And John, who’s in the book. Features in the book. Quite pro pro prominently.

John is an Australian guy who got a scholarship to study in Japan. When he was 16, 17, he went to Japanese university, did everything fully in Japanese, wrote his, ro bo graduation thesis, by hand in Japanese, has been studying tea ceremony for 40 years. He ran, he was the CEO of Sky tv.

This thing found it with Rupert Murdoch in the early nineties. He was, anyway, this total, wonder, wonder Kin, impress, RO amazing amazing guy. But he was walking when he was 17, 18, 19. All a lot of these old roads that I’m walking now. And he started walking them again in his fifties and he started inviting me.

He’s connected with the art world. He did a lot for getting aboriginal art to display around the world. I remember 20 years ago there was a couple of big exhibitions that kind of tried and he catalyzed a lot of that. And so he was involved with art. I was involved with art in Tokyo, and we connected through that.

And then we had this sort of shared love of walking and this history, and John really showed me how to do these walks in a way that. There’s a richness there. And I describe in the book how he showed me, but a richness there that I would’ve never been able to imagine on my own.

Yeah. There’s these old pilgrimage roots really, that he that he walked himself and then reintroduces you to and you even have a, like a GPS connection at certain points, right?

He can track you and send you little notes. You call it the Book of John. But it’s wonderful to have that kind of dialogue that’s maybe not interrupting your own thought process throughout the day, but is something there for you to come back to and reor to. But I actually wanted to go back to Kevin for a minute.

‘cause one of the other things I think about in terms of Kevin, is this idea of the thousand true fans which I think is an idea that we’ve talked a bit about in our friendship. But you have launched this thing called special projects that really in between all of these different publishing ventures and things like that really supports your practice.

And I, I think it’s so unique. I guess I would love for you to talk a little bit about it too.

Is anyone here a special projects member? Awesome. Great. I get to this opportunity to convert all of you. You can join today, lifetime membership 1500, but it’s just a

different way of interacting with your readership or something

like that.

Yeah, so that I started my membership program and it’s, it funds everything. It funds my entire life. It is the financial basis for me to do everything that I’m doing. And it also gives me a kind of permission to do these big walks, which, I started because I had been, I’d been writing these big magazine pieces and I wanted to write about walking in Japan and I’d been doing this huge, working on this big piece for the Atlantic for months and months.

And then I got ghosted and it was really painful. It just sucked. And there’s this moment of, okay, what do I do? Why is this happening? Do I know how to, do I know how to write in a certain way? Do I, and I talked to a bunch of my journalist friends who were all saying look, you have an audience already.

You know what you wanna write about. You’re in this perfect position to launch some kind of membership thing. And so that was the catalyst. It wasn’t because I wanted to do a membership program, it was because I couldn’t, I was rejected by traditional forms of publishing. And this book too is a weird, a milestone for me to have random miles.

Publish something of mine. I’ve been doing indie fine Art limited edition books my whole life, and so this is quite bizarre to have a big five publisher publish it. But it was really starting special projects was just how do I give myself the permission and how do I create a financial basis for me to do this kind of work?

And it took a while. It took about 18 months before it really became something. And 18 months into it, I COVID hit. And I put together this book called Quia by Quia, and I thought, okay, I’ll make a thousand copies. It’s a hundred bucks a copy. It was about a walk from Tokyo to Kyoto and I was eating pizza toast the whole way.

And it was about these Japanese old style Japanese cafes. And I thought, okay, a hundred bucks. I’ve done enough books in my life where I know a hundred dollars book, a thousand copies, it’ll take two or three years to sell them all, and that’ll be great. And I thought, okay, I also want to offer my members a discount.

And I’d done Kickstarters in the past. I did a Kickstarter for Artspace, Tokyo, 15 or 16 years ago. It was one of the first book Kickstarters actually, and that went really well. I did another one in 2016 that went really well. And then I looked at Kickstarter again in 2020, and I was like, this platform hasn’t been updated in a decade.

And I’m like, they take such a big cut. I can’t even offer a discount. I can’t even offer a coupon to people. And I was like, this is lame. And so I started looking at Shopify. I never used Shopify five before, and I’m really kicking myself because as soon as I started using it, I saw amazing.

It was, I bought a bunch of Shopify stock and I like really wish I’d done that 10 years ago, not five years ago. And I was like, Shopify’s incredible. This template system’s amazing. I wonder if I could clone Kickstarter in Shopify. And so I built Craig Starter and it was pretty easy to build.

And this is before LLMs. I didn’t use

sidebar. You’re also like an engineer, like you can code.

My degree in computer science and fine arts. So that was, I did a lot of, it was more math heavy than actual sort of trade computer science, but a lot of theory. But yes, I can jump into templates, I can do whatever.

I can make Craig Starter and launched Keys up by Keys with Craig Starter with the discounts if you were a member, and the conversion rate for members to buy the book. So the book’s a hundred bucks if you become a member, which costs a hundred dollars. You get like a $40 coupon, so you could buy the book for a hundred bucks or you could buy the book for $160 and 30 or 40%.

It was insane. Percentage of non-members converted to member to buy the book and we sold out in basically a day and I was just like, oh my God, this is weird. Talk about product market fit. I did not. I truly did not expect that to happen and that. Moment of, Shopify, the system, me setting up this distribution system in Osaka, this interest in what I was doing, physical, the physical object, the fine art object, being able to sell at that price all coming together, that set in motion everything I’ve been doing for the last five years and it created this business foundation for my life that.

I’m really proud of, because it’s completely uncompromising. It’s so uncompromising.

So many people I think, go to college, get the MFA get the agent, get, publish their first novel. And it’s starts in the classic mainstream publishing world in a lot of ways.

You did everything else first and arrived here. It’s just a fascinating trajectory.

I tried to do the other way and I just got rejected. I got rejected by everybody. Everybody rejected me 10 years ago. I was trying to sell a book. And I got gas lit by so many agents. Honestly, like I thought I was losing my

mind.

Do you have, I mean for, we have a lot of writers at Notion, we have a lot of people, creative people at Notion, maybe, do you have any advice for them?

I’ve been so traumatized by the process, right? And I think also because of where it came from. From a very early age, I felt okay, I have to own everything.

There are no adults in the room. That’s kinda what it felt like. I intuited that and so over the last decade, you know what I’ve built up in building up this special projects system and then my own fine art imprint is creating this floor where I don’t need random house to publish me because I have the system set up.

I have these super fans that, thousands of. Members, active members in the system. It is such a great community. It’s such a, like a community of so much love and support. And so for me, I needed that safety net that I had to build myself and own myself before this could happen. In the random house thing too, it was really interesting.

I pitched and everyone was silent and I decided I’m gonna do the fine art edition on my own. And then it was three months into doing the fine art edition where I committed to it, and we were pretty far along in the process. That Random House said, okay, hey, we really love this book. We want it.

And I talked to them, I said, look, I’m already doing my edition. It’s really important. I maintain fine art rights because. I can’t give that up. You were saying sinners, this new movie, sinners, the director, Ryan Kler. Ryan Kler kept a lot of his rights. Yeah,

he has I think full ownership is film negatives so that he can basically release it in lots of different forms, so like within the studio system, but also out different and more authorial ownership than the studio system would normally allow.

So for me, it was important to keep the fine art and I said, look, we’re not gonna compete. My books could be a hundred bucks. Your books can be 20 after discounts. Also, like we’ll do a full nother rev on it and the fine art edition came out 18 months ago and you know this one’s coming out now. This is double the length.

The shape of it has changed completely. And by putting mine out and feeling like I, I had done a version that I was really proud of. It allowed me to relax creatively. And so my editor Molly at Random House, who’s wonderful, who totally got the book, totally got what I was trying to do, which is why I agreed to do it.

Because it wasn’t about being blessed by Random House or being seen as official or whatever. Even though there is a weird status thing that comes with being published by Random House, I’m feeling more and more it wasn’t about that at all. It was about having a collaborator that. Really got the book and worked on this level that I didn’t work at, more of a mass market level.

And she, her response to the other manuscript was to put three or 400 questions in the manuscript. And then I spent, this book is basically a response to all our questions. And we built out from that and then reframe the whole book as a letter to Brian, which felt like this powerful moment, it’s transformative in the other book.

Yeah I

have both books and they’re both wonderful but very different. And I feel like, yeah, I would love for you to talk about some of those questions. That she asked you and what they unlock for you Because I, I found it was transformative.

A lot of it was, I, I have my. Members who are super fans who know a lot about me, so I don’t feel like I have to give context.

So I don’t give a lot of context. In the fine art edition, it’s much more minimalist, and this just it. Imagine you’ve never heard of me, you’ve never read any of my writing, you’ve never read any of my newsletters. You can pick this up and it makes sense. So a lot of it was that, and it turns out that actually writing about that stuff and fleshing out the relationship with Brian, our history, and then reframing it as a letter to Brian, allowed me to bring in all these other characters because Brian was foregrounded.

So just in terms of craft the Fine art edition, Brian kind of sneaks his way in and then appears at the end. This one, he’s there from page one. So he was there, he was protected by being there in the foreground. So I could bring in John, I could bring in Asura, I could bring in these other characters that aren’t in the fine art edition.

So unlock this whole, these other layers of narrative that I think it works really well. That’s

so cool to see. I want to pause for a second just to, I know we’re getting close. We have about 15 minutes, so we can, I have some quick fire questions for you, but I don’t know if we have any questions from our Dory, I’m just gonna check here.

Oh, I think maybe there’s a couple. One sec. I’m waiting for them to load. While I wait for these to load, I will just maybe ask you a fun question that I thought of, which was, so I saw in your Instagram the other day that you were like, you were at three lives and you were excited to be in the window of three lives at one of my favorite bookstore also in New York.

But which two books would you want to be on either side of this book in three lines? There were books on the sides already, but if you could pick, if you could merchandise the window, which two books? God, what a

good question. Probably rings a Saturn or Snow leopard. And Pilgrim, tinker Creek.

Annie Dillard. Nice. Peter Meth. And Sal,

for folks that don’t know those books, do you want to say a word or two about why you like them so

much? Yeah I think Sal, like the way we deal with photography in this book is different than the fine art edition and a lot of the photography is illustrative in line.

And Saal, I think does that really well in rings of Saturn. And he’s, his book is a book of walking and I can drew inspiration from that for this and the associative qualities of what I’m writing about. And then Annie Dillard, whenever I have a, any moment of writing write or writer’s block, I just pick up pil, tinker Creek.

It just reminds me of what writing can be and should be. It’s this kind of joyfulness, this lightness, this beauty, this pop, this poetic nature that you can give to any, almost any event in life. And I think Annie wrote that book in her earlier, mid twenties. It’s she was.

So good so early. That book reminds me of that on every page. Nice. I just love it. Nice. Okay.

Aria has a question and you’re in the room. Do you wanna ask it in person? Sure. Okay,

Audience: thank you. Hi Greg. Hi. This is really great. I was curious, I felt like you answered it about why and how you got into the process of walking, but to me it sounds like having a mentor. Being, this tradition, being transmitted to you was a big part of that. Is that true? And then if so, do you feel like you have any interest in transing that tradition to others?

Or do you feel like your work does that?

Craig Mod: That’s a good question. Japan, and I think Europe has this as well, look at Spain, you have the community of Sant. England, all of the rights of ways. I think Europe more than America has a big walking tradition, walking history. It’s implicit.

And Japan also, and most of it’s connected to pilgrimage because you couldn’t travel two, 300 years ago in Japan. You needed passports to go from one domain to the other. Everything was quite strict. And the one thing that you could say, Hey, I want to go do this, and they’d let you go do it was a pilgrimage.

So a lot of these roots are pilgrimage route. And for me, I loved walking in Tokyo when I was, when I first arrived. Just because again, the sense of archetypes and lives being lived and there’s a smallness to everything and a compactness and kind of a density to it, but a piece to it all. And I’d walked all these back streets.

I usually, I’d be drunk. I really struggled with alcohol throughout my twenties and I would be on the edge of blacking out doing these big walks in the middle of nowhere of Tokyo, just feeling a kind of love. From these, the sounds of families behind, everything’s close. You can hear every, you can hear people in baths, you can hear the radio, you can hear the tv.

You can hear people having dinner. And so that was always implicit. I was always drawn to that. And then John, because he was studying Japanese literature and because walking is so intrinsically connected with Japanese literature, like Bacho, the Haiku, he did Amichi, the narrow road to the North, it was a big walking book, so there’s a lot of walking in Japanese literary history. So John, to better understand Japanese literature, started doing his walks when he was 18, 19, 20. And then when he retired in his early fifties and he started doing it again and started inviting me, we just get along too.

We’re just like good travel buddies, like super good travel buddies. Like just so easy to, I like, I wish, John’s 20 years older than me, like I wish. I, it’ll I wish we could be married in a way ‘cause it’s so easy life, like traveling with job. We’ve traveled together probably for six or eight months of our life and it’s some of the easiest traveling I’ve ever done.

But we’re essentially like brothers. That’s what it feels like. And he’s kinda like my big brother and, starting to go on these trips with him and being so easy and immediately watching him in Japanese. His Japanese is so imperial and beautiful and ENT and watching him. Give so much respect to everyone we met along the road and seeing how that respect elevating these people we met, changed the people in real time and change how they looked at us and change how willing they were to support us that I had never witnessed before.

And to watch that again day after day for six months, eight months on the road together. That formed a huge basis for what I’m doing as I’m walking, and it took me a couple years of walking with John before I felt like I had. Earned the right to go off on my own. Yeah, that was a big part of it.

It really speaks to the, the power of language to build community, to build empathy, to build, build bridges really like it is amazing to watch. He’s like a magician in the book when he inter interfaces with people. It’s

unbelievable. And for me my default stance is let’s fight, like that’s my default.

Let’s, okay I’m gonna, I’m gonna kick you in the neck. That’s like my default. That’s like the voice in the back of my head is always ready to fight. If anyone slights me, if anyone I perceive to be a bully, to be discriminatory or whatever, it’s immediately I go to the worst possible reading of it.

And that’s just because of where it came from. And because you had to protect yourself. And then to watch John, who clearly came from this place of abundance, a family of incredible love and just resources to not go there. Treat everyone with the sort of, from the best possible assumption and then to elevate everyone and watch these kind of mean people who start off quite mean towards us.

Change and fall in love with us and offer us all these things. Just in the span of 5, 10, 20 minutes of talking, it’s wow, okay, this is a way to operate in the world as well. And just, it’s something I wish I could bring back to Brian and me as a kid. It’s something I talk about in the book if we had one person like this in our childhood, how differently would it have been to not go towards the violence?

But

Brittany, who made today don’t. You’re good. Okay. Alright. You made today possible, so we’re gonna thank you anyway. But yeah, no, maybe another question for you is about like a walking bucket list. So you. You have walked both UNESCO Heritage Route, which I’m very jealous of because I am like a nerd about UNESCO heritage sites in general.

But like what about what’s your next do you wanna do the Alps? Do you want to do, like, where do you want to go?

I like ReWalk. I like this, I read about this book. Yeah, you actually,

it’s a great part of the book where you talk about you can only know something when you’ve been there second time.

Yeah. Second, third, fourth, the Peninsula I’ve done. 20, walks of some of these roots, and I even just went back. I’m always like, okay, this version of the book, I’m done. I’m never gonna write anything about the Peninsula. I’m never gonna do anything about the Peninsula anymore.

I gotta a break. I gotta do a break. And then in February I went, I did a 10 day drive. That was pretty radical to rent a car. I, but I had to move fast and I wanted to photograph the people of the peninsula. And I shot this book, it’s called Other Thing, and this comes out next week. I shot this. In a manic sort of fuss.

Amidst all of the random house prep, because I wanted to go back and I wanted to honor the, all the people I’ve been meeting and take portraits. And also I’m really paranoid about getting creatively soggy, and there’s something that, I’ve been working on this book for four years and the fine art thing came out 18 months ago.

This thing is coming out this week. And it’s a long time to sit with one project.

You’ve rung it out like you, I’ve rung it

out and I’m like, okay, I don’t have time to do this book, but I feel like it’s almost like an aesthetic practice and I felt the need to shove it into my schedule to do this 10 day.

Thing where I’m, getting up at four in the morning to go get on tuna boats and photograph the sailors and the market people and, the, in the innkeepers and, the pearl divers and all this, all these different people, these sort of monks and stuff and of all these critical places in the book.

But producing this was a way, I felt like how do you keep sharp in the face of the softness that can come from doing something with a, with. On a bigger stage. And so remembering the roots, being really aesthetic about that,

you don’t wanna lose your edge,

basically. Don’t wanna lose the edge. Yeah. And returning to the Peninsula yet again and doing this project, I thought, okay, I’m definitely gonna be done with this thing now.

And then in the middle of doing this, I realized there’s another project I wanna do on the peninsula. So re-walk returning. Revisiting is really critical. That said, I’d love to walk the Dolomites, I’d love to walk a bunch of Ireland. I just think Irish people are amazing. I think Ireland. It is great. Plus one.

I want to, I’d love to go up there. I’d love to do some Scottish walking. I’d love to do the full Camino. I actually haven’t done the full French Camino. I’ve walked the first 150 K, the last 120 K, and I’ve walked the Portuguese Camino from the border of Portugal and Spain to Santiago. But I haven’t done the full French.

And I think if anyone’s thinking about doing a big solo walk, I would say the French Camino. It is so much better than I thought it would be. And, it’s so well known. Emilio Estevez did a movie, a really bad movie called The Way. Yeah, it’s terrible. Ter, he dies on the first day of the wa spoiler alert.

He dies immediately, by the way, that, that first day is very easy. If you die on the first day, you weren’t gonna make it that far. So he dies and then whatever. It’s a very weird movie. But I thought it was gonna be like Disneyland. I thought it was gonna be overly touristed. I thought it was gonna be terrible.

And it just turns out it’s a five week walk, basically. And anyone who commits to something of that scale, it doesn’t matter if it’s touristic or you bond in a very strange way and it’s moving. And the cities and villages are beautiful. So if you’re looking, if you’re like, oh, I need a sabbatical, or I need to, I wanna go do something, I wanna like reconfigure, rethink about life, go do the Santiago.

Alone. ‘cause you will meet so many people the way it’s set up, you organically meet as many people as you want or as few people as you want. And I think it’s really powerful and I want to do the full thing at some point. But gotta find five

weeks. Yeah. You know where to find me.

Yeah.

I wanted to, if you wouldn’t mind, close with just like a little paragraph of your book to just read one of my favorite parts of it.

So let me do that and then we’ll thank you for coming. But this is where. It’s a couple page, it’s a, it’s maybe 30, 40 pages in Craig has stayed at a bed and breakfast on the road with a family. It’s not the cleanest bed and breakfast. And there is a moment when you’re about to leave to go on your day.

And a woman appears she seems like she’s a daughter in the family. And I’ll go from there. Just then a woman who looked in her mid thirties opens the front door, strolls in as if she’s been waiting for me to finish. Oh, hey, this is our daughter. The wife says hello. Nice to meet you. Your parents are trying to murder me with bread ‘cause you were carbo loading at the time.

She laughs. We chat a bit, but I have to get to walking the distance. Loomed large, about 25 kilos with significant elevation to the next inn. As the husband drove me down to the mountains, back to the east a G path, he broke our silence by saying she ain’t our daughter. I’m entranced by something out the window beyond the fields, past a dirt road in the forest.

Something burned before I register. What he said, he comes back with more fluency. She just appeared years back, wandering the country, needing a job, somehow found us. Not a daughter, but like a daughter. Time passes, life moves, and that’s what happens. Things become other things. Thank you, Craig. Thanks.

Can I last word?

Can I add one postscript yeah, do dorky. Super technical. It was great when

I hit that, I was like, this is beautiful.

Oh, thank you for picking that. Yeah. That’s where the title comes from. But I just have one more thought about, being independent creators and thinking about owning your own space online.

I’m pretty pathological about not being dependent on obviously a lot of things in life, but also platforms. And so my membership program, I’ve coded up the entire backend for it. It’s in Flask, it’s a Python app. And I think this is really important. So thinking about things like, should I launch on Substack?

Should I do this, should I do that? If you have technical acumen and you have the ability to create a space of your own, I found it to be really powerful and. A couple months, basically a month ago, a month and a half ago, Claude Code launched and I thought, okay, I need a project for this. So I’m like, what if I cloned Twitter just for members?

And I, I have really rigid rules about how I want it to work. Only two posts a day, you can, all the photos are just in one bit, black and white. You can click ’em to get the color, but otherwise it’s quiet. And then everything disappears after a week. So it’s all ephemeral. And to have this space that isn’t discord, that isn’t slack.

And so I used Claude Code, programmed it together with Vibe Code in it or whatever, and created this space that it’s called The Good Place. Has anyone seen the TV show The Good Place so that if you add it to your home screen the icon is Ted Danson’s head? So you get to click to Ted Dan, Hey, did Ted Danson’s head, it opens up and it’s this kind of Twitter clone, and I thought, okay, this will just be fun to throw up there.

And it has turned into my favorite place online. It is such a great community. The energy there, the posts, everyone is so loving. It’s so great. And I don’t think it could have been built anywhere else. It’s because of the bespoke nature of building this thing and having this space and owning this space that people, I think, rise to it in a different way than Discord or something like that.

And so anyway, that’s just something I’ve learned over the years that I wouldn’t have thought could be that powerful. But it turns out. It

is. I love it. The publishing experiments continue. They

continue. I can’t stop.

Go visit The Good place. Yeah, the good place. Thank you Craig mod for coming. Thanks for having me.

This was so much fun.

Thank you.

Thanks Notion.

Great. Thanks Rob.