On Margins is a podcast about making books and book-shaped things, hosted by Craig Mod.

Subscribe on iTunes, Overcast, Google Play, Spotify, and good ol’ RSS.

007

Lisa Brennan-Jobs and the design, production, and writing of memoir

Lisa Brennan-Jobs

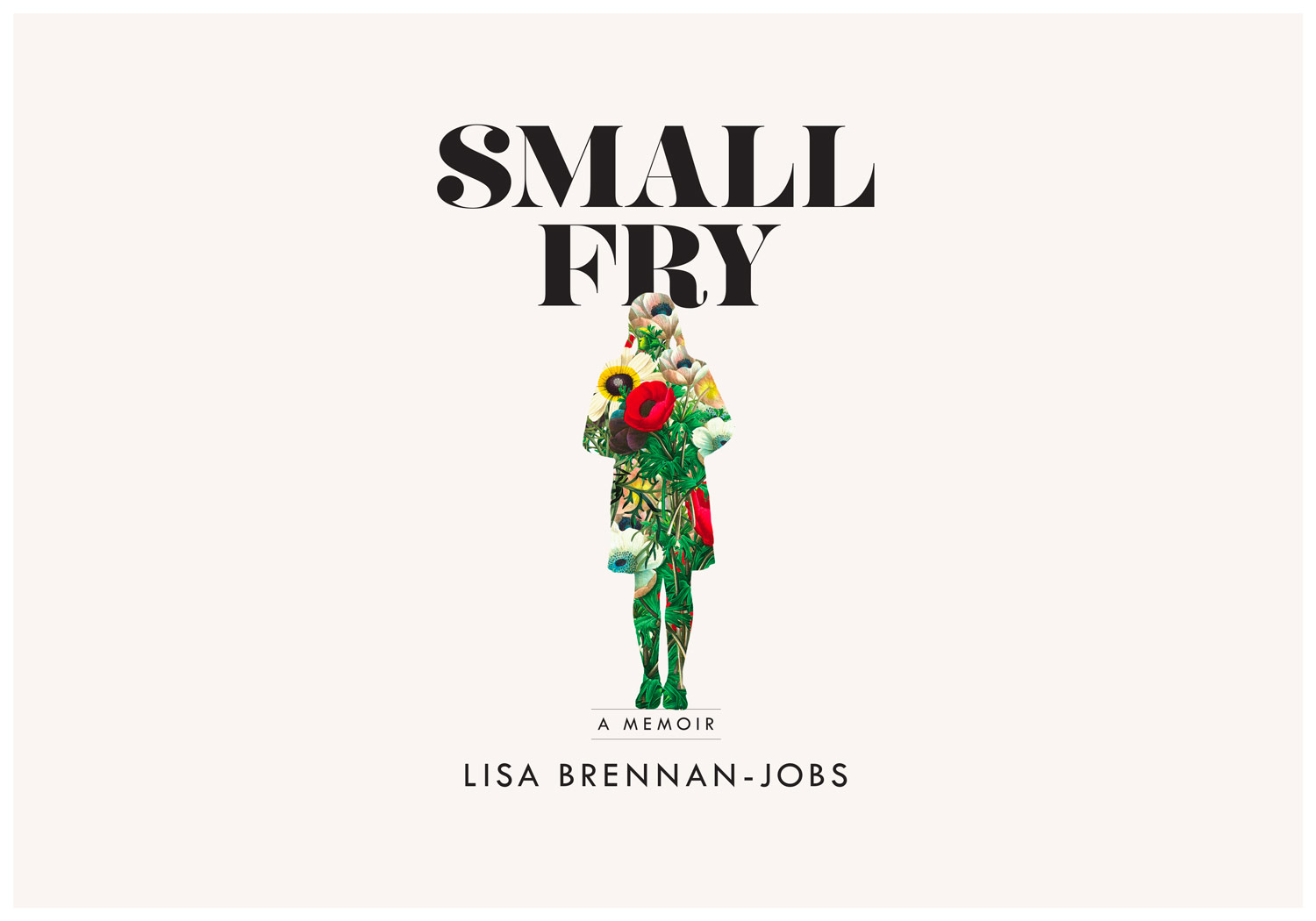

Small Fry

An interview with Lisa Brennan-Jobs, author of the best selling memoir, Small Fry. Lisa and Craig Mod discuss the design, production, and writing of this fascinating book about family, identity, and the complications of growing up in Palo Alto as the daughter of Steve Jobs.

Show Notes & Links

- Lisa on Twitter

- Small Fry the book

- Hera Big font

- Book designer, Alison Forner

- "The Subtle Genius of Elena Ferrante’s Bad Book Covers"

Full Transcript

Craig Mod: You’re listening to On Margins.

I’m Craig Mod, and this is episode 007.

Today I’m talking with Lisa Brennan-Jobs, the author of The New York Times bestselling memoir, Small Fry. It’s a beautiful, delicate portrait of the struggle one sometimes has with the fuzziness of family, especially the fuzziness around blood, who’s in or out, who is true family or false family.

Even though the book is mainly about the self-actualization of a young girl, it resonated with me at a very fundamental level. Personally as an adopted person, I’ve spent my whole life grappling with where and how those lines of family are drawn and how they can shift unexpectedly beneath your feet, sometimes in truly tragic ways.

There’s a tenuousness to life when blood doesn’t explicitly bind you to anyone. Small Fry digs into these sorts of thorny issues. It just so happens that Lisa’s dad was Steve Jobs, so there’s this added surrealist element to her exploration.

It also turns out that the book has a killer cover. Lisa and I dive into how the cover and design of the book came to be, how she ended up choosing her publisher, and what the writing and publishing process felt like. Here’s today’s episode.

Craig: Good morning, Lisa. Thanks for joining me today.

Lisa Brennan-Jobs: Thank you so much for having me.

Craig: Let’s just start on the outside of the book and work our way around it before going into it. First of all, it’s just beautiful.

Lisa: Thank you.

Craig: It’s just a gorgeous book.

Lisa: That’s high praise coming from you.

Craig: It really is. It’s striking. It’s got all these qualities of what I think make beautiful covers, beautiful kerning, wonderful typography. I think you’re using Hera Big on the cover there?

Lisa: That’s right. It’s a new font, and I was actually worried about it because it’s not very chic in a certain way. It’s not very modern. It’s not like italic Helvetica Bold.

Craig: No, it’s definitely not.

Lisa: Already I was dealing with a major, major exposure of myself in the work, and so I was hoping there would be something about the cover that would be unassailably fine, ordinary, normal, or something like that. I worried about this Hera a lot actually.

Craig: Because you thought it was cut of a too contemporary cloth?

Lisa: Yeah, and I was worried that it was based on an old font but that perhaps it hadn’t yet stood the test of time and it might not have the same refinement. Did it have extra on it? What were those balls? What were those dangly, dongly things?

The one thing that I knew I wanted to do was have a large title because I was already naming my book a diminutive. Small Fry means insignificant as well. I thought I can’t name my book small and then have the title also quite small.

[laughter]

Lisa: It’s like what am I doing, trying to disappear? I wanted that to be big for contrast, but then I also just wanted it to be stylish. I worried that the Hera Big and my name were different fonts, that there was a serif font and a san-serif font.

Actually one of the things that put my worries more to rest was that when we adjusted the kerning of the title then somehow…You know how kerning is…I personally, you probably can do it yourself, but I wouldn’t know how to do it, but I can tell when it’s done. When it’s done it feels like an eyeball massage.

Craig: [laughs]

Lisa: Like aah.

Craig: That right. It’s OK, it’s fixed now.

That’s good.

Craig: That thing that I didn’t even know what was wrong, but it feels good.

Lisa: Now I will feel acceptable when this is out there in the world.

Craig: You worked with designer Alison Forner on this?

Lisa: Mm-hmm.

Craig: She’s got a great collection of work behind her as well.

Lisa: She does. I liked the fact that it seemed like on the masculine-feminine balance. It didn’t seem like it was either one particularly. I also liked the way that she seemed to be comfortable playing with fonts and incorporating them quite well into her designs.

Craig: That Small Fry font, that Hera, to me it feels perfect for the book because it’s vibrating in this weird space.

Lisa: Exactly. [laughs]

Craig: Your book looks like it came from 1978. It really feels like something that came out of a different era, like a different “Bonfire of the Vanities” could have had some cover that was in that class. It almost feels like it’s of that Tom-Wolfe-kind-of-novel era.

Lisa: There was a great cover actually that I had sent the designer that I liked of Sylvia Plath’s “The Bell Jar” where there’s a fabulous ’70s font. Maybe that was part of the reason she was inspired to use this. I don’t know.

The other thing for me is that in addition to wanting the title not to be so small that it would cause the book somehow to disappear, I also was terrified of being misleading. This is not a book about my father. This is a book about a girl coming of age. I really didn’t want my father’s picture on the cover.

I also, in retrospect, it might not have been a great idea to have Helvetica Sans on the cover because that might have also seemed as if it was borrowing from him. That was really important to me.

Also in terms of representing the book correctly to not have it be sad. Some people are taking sadness from it, or they’re taking, some people have said, “I’m laughing. Am I supposed to?” I’m like, “Yes, please. Laugh. It’s supposed to be funny.”

It was important that there was a certain playfulness. There always is really good design. It’s so playful. That’s what I love about it. It’s so fresh.

Craig: How much of a battle was that to keep your dad’s face off the cover with the publisher? I’m sure they were just like why don’t you just call it, you know, Steve’s Daughter?

Lisa: The Steve Jobs Daughter Story, but daughter and story are really tiny. They were amazing actually. My publisher has been amazing. I switched publishers later in the process. I switched from a larger publisher to a smaller, independent publisher, partially for that reason.

To be honest, even the larger publisher had been quite clear when they bought the book that it was going to be a literary memoir. I had control in both cases. I had final say in both cases over the cover.

There’s a tricky thing that happens, and I wonder if you’ve experienced this or even perhaps been on the other side of this. It must be frustrating if you’re working with someone creative and you have some idea of time, and they don’t. You have no control over their process. One of the ways that business interacts with creatives is that they run out the clock.

They’ll say, “You know, we’ll just do a few covers, and then we’ll get them back to you. If they don’t work, then we’ll find a new designer, and we’ll redesign it.”

Having worked on the book for what I’m saying was seven years, but I’m sure it was more than that, I had become savvy to the ways of the publishers a little bit. In this case I thought no, what might happen in that case is that we run out of time.

Literary people, especially these incredible publishers that I have, their field is not design so that perhaps they don’t think of it as taking so much time. What I worried might happen is if we didn’t find the right designer right away, we might try to find a good designer at the last minute and then tell that good designer to work quickly, which doesn’t work well.

Craig: Also there’s a disconnect between the amount of time spent on the manuscript and then the amount of time spent on the container for it. That doesn’t feel right either.

Lisa: That’s always going to be true in this case because they couldn’t spend seven years on a cover.

[laughter]

Craig: No, you don’t want to spend seven years, but you also don’t want to just at the last second be like, “Wow. Well, we’re out of time. Let’s just, OK, we’re going to throw this person on it.” That’s not healthy either.

Lisa: It’s similar to the way we were talking about reviews. Books are so time-consuming to write often, and it’s such an incredible process that the idea of being hard on a writer, of writing a scathing review of a writer is just, it’s so problematic why wouldn’t you just turn away?

I do agree with you about a cover. After all this work, the writer should be happy with their cover. Design is often, you don’t know why you’re happy, but you know when you are.

You’re one of these rare people. You have a background in design.

Lisa: I hope so, but I never could have designed a cover. I certainly did not tell the designer. You might tell me something was wrong with a scene in my book, but you wouldn’t necessarily know how to fix it. Sometimes that mistake is even made with writers where people say maybe you could do this, and this, and this, and that would fix it. Occasionally that could work.

The rule I’ve often gone by is if someone notices something wrong, they’re almost always right that something is wrong, but their way of fixing it probably isn’t. To listen to the problem, but you have to find the solution for your own work yourself.

Similarly with designers, it can be tempting to say, “Well, what about you try this. Or what about…” Obviously, that can work with spacing in between letters, but before the design is fleshed out, it’s really just a conversation of what, you find the good designer, and then it’s a conversation of what is the book about, what does it mean. Then it’s their job to translate meaning into visual imagery.

I didn’t ever present any ideas. The one thing that I did talk to her about is her original designs were a bit negative. I wanted a more balanced and positive interpretation to be on the cover because that’s how I feel about the book. I did tell her that. Aah, don’t be too negative.

Craig: That kind of direction’s really important. What I was saying earlier just about writers having taste around the sense of what’s going to work in a market or not work in a market.

Lisa: They don’t know what works.

A lot of people don’t. Your point about time is really important because that’s what define that place where both the publisher, who ostensibly has some insight into how to position a certain thing in the market to get the most traction and have the widest audience in a positive way, and finding the balance between the cover that achieves that and then also the one that the author is pleased with.

That’s where the time component, that’s where you’re really smart to push for things not to be held off until the last minute.

Lisa: Again I’m not sure if we know how design really relates with market appeal. People do gravitate toward beauty. You can’t ever sell people short on their taste. Sometimes they don’t get the pretty thing maybe because it’s too expensive or because they can’t find something they actually like.

In general sometimes this idea of marketability is fashioned, and isn’t researched, and isn’t necessarily true. Another thing is sometimes a book is so good that it doesn’t really matter what the cover is, and maybe then they think it was the cover that did it, but actually it was the book. I think…

Craig: Like…

Lisa: Yeah?

Craig: I was going to say, just to that point, like Ferrante’s…

Lisa: Right.

Craig: Those covers, I haven’t read those books because of the covers.

Lisa: Because you can’t stand the covers, and so you don’t read the books?

Craig: Those books have been recommended to me so many times. They’re a little bit outside of my normal reading universe.

Lisa: Fiction, women.

Craig: No, I read lots of female fiction writers. I’m actually just finishing right now “Asymmetry.” It’s by Lisa Halliday.

Lisa: I’ve heard that’s great.

Craig: It’s so totally blown me away.

Lisa: I keep on hearing that one’s great.

Craig: It’s so good. That’s also got a gorgeous cover, this beautiful, folded, paper airplane cover going on. Also “Crudo” by Olivia Laing. Lynne Tillman’s latest novel.

Lisa: What is it about the Ferrante book that seems – I’m pronouncing it in my Italian way, the Ferrante…

Craig: [laughs]

Lisa: that seems outside of your reading universe?

I read mostly novels of ideas. The female part of it is, none of that is a turn off. It’s like I look at it, and I go, “OK, that’s a novel of story.” It just feel like intensely story-driven.

Lisa: It is.

Craig: I haven’t read any of the Harry Potter books either, which I should. I’m sure. It’s just funny. With the Ferrante novels in particular, the covers made me feel like they were intensely novels of story in a way that pushed me away from them.

Lisa: It’s true. They’ve leaned into their genre so much.

Craig: There’s probably a bunch of people who did read it because of that cover that wouldn’t have read it otherwise. It’s a weird process.

Lisa: We definitely do judge books by their cover.

Craig: A little bit.

Lisa: I’m still not sure the publishers understand all of the complicated calculations that go into that judgment. I think sometimes when they push people to do something for marketability, it can be a false certainty, just the way sometimes when they have people cut certain parts out of their book for marketability, it can also have a false certainty to it.

Sometimes they do know, so it’s hard, it’s really hard to know.

Craig: [laughs]

Lisa: What I would try to do with my book is, certainly the inside and what needed to be cut and what could stay, is just to have a gut feeling with certain things. There were certain things that my editor had said, “I think you can let that go,” and I couldn’t.

Finally, when I read it over for the last time, and I was only allowed to make changes to one percent of the book or something like that, finally then I would say more than half of those sections – there were only a few left, maybe four or five left – I thought, “OK, now I can cut this.” It wasn’t until I knew.

I felt the same about the cover that I…I, in part, had moved to a publishing house that’s independent and had changed to a much lower book advance so that we could make decisions based on the book, not based on the quick marketability.

The marketability, of course, was always going to be based on my father. That would be tricky for all the people that were dearly hoping to pick up a book about Steve Jobs and were going to end up reading about a young girl.

I felt especially worried about that in the beginning. Now I feel less worried. Now I feel like I’ll trick them, and then they’ll be happy, and they won’t know why. In the beginning I thought they would just be so terribly disappointed. I had to save my book from false disappointment. The way I had to do that was somehow show some degree of joy and show a girl. That’s what I was hoping for.

In the beginning, the cover’s she had produced, there was a girl spinning in the darkness. The girl seemed too pretty, certainly prettier than I was or am, but also pretty in a way that somehow didn’t seem like a child. I like the way that she did the flowers. They feel at the same time sweet, and reaching, and longing, and also sinister.

Craig: There’s something very melancholy about it.

Lisa: Do you think?

Craig: Again it’s this vibration between two spaces here that’s going on. You feel the youthfulness, the youngness, of this silhouette of the girl. It’s funny the way the flowers are placed. It almost looks like she’s holding them.

Lisa: It does, doesn’t it? Holding them out almost.

Craig: Yes, holding them out. There’s a quietness there that could almost be on her own in a field somewhere or in some ways a little bit like a funeral.

Lisa: That’s interesting. There are chrysanthemums as well. Aren’t there chrysanthemums, or are there…Maybe there aren’t. They’re anemones and poppies. Anemones might have something to do with death. I’m not sure. They’re certainly a more bold and dramatic flower, and then the leaves of the poppies look a bit like veins.

Craig: They totally do. It all connects so well with the book. Your big trick with this book was you didn’t want people to get a false expectation for what the book was about, but it almost didn’t matter because you pulled that dirty trick of writing well.

Lisa: I know, ha ha. Thank you.

Craig: It’s like when you have a great professor, it doesn’t really matter what the topic is, you want to follow that person into the deepest folds of their minds about the stuff they’re interested in.

Lisa: It certainly doesn’t matter what they’re wearing.

Right. I just feel like, and a big part of the book is obviously coming of age, and it’s, there is this kind of mourning for again this vibration between being part of a family or not part of a family. Should I be elated? Should it be a party, or should I be again mourning the loss of this connection?

It’s a very hard act to pull off, but I feel like this cover hits all the notes. It gets the time right in terms of when a lot of the book takes place.

Lisa: California, ’70s, ’80s.

Craig: Totally. It just completely nails all that. It’s really one of those rare, lovely covers that it feels as smart as the book that it’s covering.

Lisa: Thank you so much. Thank you so much. Oh, my God, Allison will be so thrilled about that.

Craig: [laughs]

Lisa: She really did so well by me. She just had an idea and went with it. It was great. She also wanted to do the rough paper. I, for some reason, got worried that it would be too expensive and lavish. The other problem sometimes with that – I’m forgetting what it’s called, what the stock is called – it’s very matte.

One of the problems can be that it becomes dirty quite easily, and that the sticker is this just…author-signed stickers won’t come off. Presumably, you’re getting something signed by the author is that it has some value, a value which is completely ruined by the sticker that won’t pick off the front of your book.

I was worried about that. She was right that the texture, especially if you have so much white space, the texture becomes important. I feel so grateful that they were willing to pay for this significantly pricier paper. The truth is I don’t know how much pricier it is.

I think it’s pricey. The publisher also went to the printers and sat there and made sure they got it right, the colors, and the alignment. I don’t know if they always do that with hardbacks, but I was very moved that they were willing to do that.

Craig: The paper of a cover, I think is hugely important. It is the thing that gives you an emotional connection to the object. It’s the thing that you feel when you’re searching for it in your bag. It’s the thing that your fingertips are against the entire time you’re reading it and you’re holding it.

Lisa: It’s true. I didn’t think about it that way. You’re right.

Craig: It’s so important.

Lisa: I talk about Franny and Zoey in the book. You know that Franny and Zoey copy, that addition, that is that matte paper that has just a few lines. I don’t know if you have that copy, but I think they still have it in the bookstores now. It’s true that I have a relationship with it also through touch. The haptic smell, it’s underestimated, I think, in how powerful it is.

Sound. I sometimes wonder if we like people and have a feeling of closeness with people sometimes because of their voices. We often think it’s the way they look, but maybe it’s also their voice. Anyway, maybe it’s the way their skin feels, who knows. [laughs]

Craig: I’m sure that helps.

Lisa: That’s the other podcast.

[laughter]

Craig: You’re very, I believe, perceptive about the dirt thing, because it’s true. The cover will get more dirty if it’s not glossy.

Lisa: I was totally neurotic. I went to the bookstore four times, “Do they get dirty? What do you think? Which paper should I use? What about the stickers?” I made them promise not to put the just signs stickers on my book, the signs.

Craig: That’s all important because this is why publishers are reticent to do things like this, because if a book has the smallest smudge on it, people won’t buy it. They’ll get it sent back. It’ll be a return.

Lisa: I know. Apparently, the publishing industry has not negotiated terribly well for themselves. They take their books back.

[laughter]

Lisa: I think they might just want to say, “You buy it, you keep it.”

Craig: That’s what I did. For many years I played by the rules, and then eventually I said, “Any new books I produce, or that I’m publishing or producing, they’re going to be sold 90 percent online, because that’s fine. Then they’re going to be sold in a select number of small bookshops that I love.”

With those small bookshops, basically I just said, “Look, I can’t follow up on invoicing every six months or whatever. You just have to buy them. I’m sorry. Look, you can buy a small number. You have to buy them upfront.” Man, that removes a lot of stress of book selling. [laughs]

Lisa: It is funny how picky you have to be to get things right. How much you have to decide what things you’re going to follow, what things you’re not going to follow, and what rules. See, I had a baby right before the book tour. It’s been wonderful. Actually, the whole thing’s been wonderful.

One thing that was frustrating was that I felt I was having to push back a lot when that energy of pushing back was exactly what I didn’t have.

Craig: What do mean push back? Against the publisher, or…?

Lisa: There was an article in a magazine that came out originally from the book, and the magazine wanted to put in something that wasn’t right, so I had to try to find a compromise with them. I compromised with them. They took my compromise, and then put in the rest of what they wanted. I said, “No, no. You can’t take the concession, and then…”

I was having to be a little bit of a fighter. Even worrying about the spacing in between the letters of the title made me feel like a diva and a fighter, and all the wrong things in a certain way.

[laughter]

Lisa: The reason I was fighting was that I felt – I’m sure other authors have felt this way – that it wasn’t about me anymore, that I had worked for a very long time on this book. Then I had to make sure it had the best life that it could have, that the people that needed and wanted and would enjoy reading it, it would somehow find their way to them.

It would be represented as much as possible in an accurate way. It was a lesson in the way the world works because I published an excerpt that was already chopped up, and that excerpt was then excerpted and excerpted into little pieces of things that didn’t mean anything.

Part of the reason the cover had to be as close as possible to right for the book and for who I am is that every element had a lot of heavy lifting to do. There were already going to be a lot of ideas about this book and about me that were going to be wrong. I couldn’t fight it in every place.

In the places where I could insist and insist for something that felt true to the book, I had to go overboard. The cover is an amazing place because you see it and you don’t see anything that leads you to believe this is going to be hagiographic tell-all, I hope, if you do, tell me. [laughs]

Craig: No. Like I said, I think it’s very, very true to the content in a way that is not always the case with a lot of covers. It’s not being stylish for the sake of being stylish. It’s not being poppy for the sake of being poppy. Everything works on that cover in a way that feels very satisfying.

Lisa: That’s what I worried about with the font, is if it was too poppy.

Craig: No, it’s of that moment.

Lisa: It seems to work. Yeah, it’s of the moment.

Craig: California in the 70s and 80s. It would be weird if you had put a medieval script.

[laughter]

Craig: If it was something like a illuminated manuscript, or something like that. That would be pretty strange.

Lisa: Think about this. I read a long time ago, I read Paul Rand…I actually saw Paul Rand speak the last time that he spoke publicly. I saw him at MIT. Then he died, I think, a month or two after that. He didn’t seem ill. He seemed great. He was just giving a lecture about his career. It was interesting. I didn’t know much about him.

He talked about how this idea of you don’t need a script that recalls China for the font of your Chinese restaurant. You don’t need to use a font with timber logs on it for your Montana lodge, that you can simply use a beautiful font. I don’t know if he was saying an anachronistic.

You don’t need to have it blend or refer to another cliché. Really, the great thing about design is looking at something with fresh eyes.

You don’t have to be, like, “Hey, it’s a Chinese restaurant.” People are going to understand that.

Lisa: There’s something cheesy and weak about having to overkill your theme with your font. That’s what I worried about with my huge ’70s font. I thought, “It seems a little on the nose.”

Craig: I guess so. For people in the…

[crosstalk]

Lisa: I’m making you reassure me, “Do you think it’s fine?” [laughs]

Craig: No. Lisa, I think we have to go back. Let’s get the time machine. Let’s get rid of this hair of foolishness. No. For people who don’t know, it’s just evoking an emotion. Not in the same way, like, “Crazy Chinese font evokes the sense of otherness, or China, or whatever.”

This is just evoking emotion in people. That’s what really important. For the most part, people are going to spend half a second looking at the cover.

Lisa: I know. Isn’t that amazing?

Craig: It’s going to barely register in their vision. It’s going to either compel them to go, “Oh, well, something is going on there, that hidden note that’s interesting to me,” or they’re going to just walk past it.

Lisa: It is interesting how many things we encounter in our lives, and which ones make a difference to us. I’ve been thinking about this with my son, because I think what actually will interest him. He’s going to have so much stimulation. Then what will pull him in one direction or another. This idea of giving children opportunities, I’m not sure it’s the opportunities that matter. It’s creating receptivity in someone.

My husband listened to this podcast. There was a man who is now a famous chef. When he was young, I think he was poor, and I think he was working in a restaurant in Queens. It was really late at night. One of his fellow restaurant workers noticed he was hungry and brought him a bowl of hot rice with a raw egg mixed in.

For him, it was a revelation. He’d never had anything like that. It was so delicious and so simple. From that, he started his whole restaurant empire. I’m probably misquoting some part of this story, but this is what I remember of it.

Craig: Isn’t this Ivan Robin?

Lisa: Probably. [laughs]

Craig: I think it’s Ivan.

Lisa: I think it’s Ivan Robin. From that story, I was thinking, it wasn’t the bowl of rice and egg because you could’ve given that bowl of rice and egg to a hundred people. It was that he was ready for that bowl of egg and rice.

That was mind-blowing.

Lisa: Right. It’s the same with a cover. It’s not always the cover. It’s just whether somehow for some reason this particular cover calls to you.

Craig: It also gives just, like, “Have you been beaten over the head with the notion that you should get this thing yet or not?” Which…

[crosstalk]

Lisa: That’s what I’m hoping.

Craig: [laughs]

Lisa: I’m hoping people have been beaten over the head that they should get it.

[crosstalk]

Craig: You must read this.

Lisa: If they’re going to look at the cover, they’ll feel like just numb and beholden to…They’ll be, like, “I must buy…” It’ll feel like a robot.

Craig: Zombie readers.

[crosstalk]

Lisa: Yeah, zombie readers. That’s what I want.

[laughter]

Lisa: The other thing that Paul Rand said during that lecture, which I thought was cool, was that if you have beautiful things, and I think he meant in your house. When you say something like that, when I say something like that, it might imply expensive. I don’t mean expensive. I mean well-considered.

" If you have beautiful things," he said, “you don’t need to worry about their compatibility because they will all go together.” I think about that a lot. Is he right? Was he right or was he wrong? [laughs] I’m not sure that’s true. That was his theory. Maybe he just meant mid-century furniture, who knows.

Craig: To peel back a little bit more the creation process of the book in general, I’m curious about a couple of things. For example, what was the first vignette that you wrote? Did you start working on this with your MFA, or was it before you started the MFA? What was the genesis moment for producing this book?

Lisa: I did not think that I would do a memoir, or I desperately did not want to do a memoir while I was working on my MFA. I did feel, at a certain point, because of the steady drum beat of due dates and essays that needed to be done, that I might as well do an essay about what had happened around my birth.

Because of that, I actually had to go and get the court records. I living in England at the time I was doing a non-residential MFA. I started actually when I was in London, and then moved to New York for the rest of it. I had my mother go to the courthouse and get the documents. [laughs] Then we got in a fight, I think because it was really stressful and awful.

open up."

Lisa: Not only that, I have this horrible wound that I’d like you to help me with, and you’re involved, and you were the one who was there.

She was trying to fax me the papers. I think that we were actually faxing papers. I think that that maybe is the most important or the most interesting part of this whole story. You’re faxing papers. She was getting them all out of order and missing pages, and then I was getting upset with her, and then she was yelling.

She very kindly did this favor for me. Then I found out that the dental records of this other man had been subpoenaed during this trial. Then I found out that it hadn’t been my mother that had sued. It was the state. I was just trying to reconstruct what had happened in a very dry way so that I could understand it for myself.

It turned out to be very lucky that I had done that because much later after I had written a full draft of my book, I gave it to my friend and my mentor, Philip Lopate.

He said, “Lisa, you just need to tell people. You do need to tell them just what happened. You just need to give them the lay of the land. Obviously the whole book doesn’t need to be a sort of essay and exposition on the past before you were there, but you do need to tell them.”

I thought, “Perfect. I’ve got it.” I plopped it in. That is the mostly in one piece explanatory essay that gives me the permission, I think, to go more slowly in the rest of the book and to not worry so much about placing you in time and space as much as I’m concerned with placing you in my own emotional life, which is more fun and which is more delicate.

I had done that in my MFA, but I was definitely trying not to do a memoir because uh, how awful, the kid of a famous person doing a memoir, barf.

Craig: [laughs]

Lisa: How was that going to be received? Also, how was I going to have the ability to make something that would merit existing, that wouldn’t just fit into this celebrity memoir category? Even if I had the ability, who would ever see it that way?

In some ways all those questions were a cover for a deeper fear, which was I feel quite ashamed about certain things, and will I have to feel those feelings again because I don’t want to. [laughs] I’d like to get through them. Is there a way to get through them without understanding them or feeling them? The answer probably no.

I thought perhaps I would do another nonfiction book first, but I just couldn’t seem to find something that was drawing me to it. I didn’t commit to writing the memoir until after the MFA. What I started with were a few scenes.

Actually, I didn’t really understand how to write scenes because I’d been writing essays up to that point which can be much more dense and much more expository than you could be in a book of this length. It would get very heavy very fast to do this book in an essay form. Also, it’s not the convention. The convention right now for a memoir is to write it in scenes.

I do understand that. It gives the reader a feeling that they’re there, and they get to parse out the details, and they get to decide what things mean. It feels more free. It feels more delightful as a reader to read that.

Anyway, I didn’t know how to write a scene, and so I started out, I think the first one I wrote was that time my mother and I went and took a couch from my father’s house when he wasn’t there.

Craig: Where you broke in basically.

Lisa: Yeah. In fact, one of the tricky parts about the book was that when I started writing these scenes, I wasn’t really in them. My editor would read them, and she would say, “It’s good. I can sort of see who your parents were, but where are you? Like I don’t even know where to place you in the room. I don’t even know what you’re thinking. I don’t know.”

I didn’t know what to do with that problem. I felt embarrassed to use the word I too much because I thought, “Oh god, how mortifying, I, I, I.” That was also telling if you’re writing a memoir and you’re worried about the word I, maybe you haven’t gotten over your problems yet.

After a while, I felt like I had to explore the more devious sides of myself, any situation where I’d done something maybe I shouldn’t have done or felt a way I shouldn’t have felt. When I started exploring those scenes, that’s when I started appearing on the pages.

Even now that scene where me and my mom go and get that couch, I like it, but I haven’t really read it at readings, and I haven’t really thought it was a standalone piece so much because actually I’m not, as a character, fully there. That’s how you can tell it’s one of the first ones I wrote.

Craig: Interesting.

Lisa: It didn’t change very much.

Craig: That’s a very common pattern when writing about your history. In a weird way, writing yourself out of it is a common technique because touching those emotional, high-intensity wires again, going back to those places can be scary.

One of the things that’s really interesting about your book is that you do get there. Even if some of those early scenes you feel like you weren’t there, it feels like an extremely emotional, vulnerable story, genesis.

Lisa: It’s funny though because now that it’s written, now that all my embarrassing stories are out there, I feel less vulnerable than I’ve ever felt. It’s almost like when they’re inside you, when there’s a drop down, and you don’t know when it’s going to fall, and you don’t know what it means, it’s harder. Now that it’s out there I think, “Eh, I guess I’m human. I guess this is humanity.”

Craig: You’ve been extremely lucky, too. Like we were saying, you don’t know how books are going to do.

Lisa: Oh my god, I’ve been so lucky. It’s so much luck.

Craig: You can pour a decade of your life into something and six people see it.

Lisa: I know, and it can be so good.

Craig: It can be so good. Six people see it. If you get one review and the review is like uh, just dismisses it or something, that is totally, completely a potential outcome for spending an insane amount of time and pouring your heart, and blood, and soul, and everything into a book.

Lisa: The way that I think about that sometimes if that happens is the positive aspect of that could be you don’t actually know how much you can change the world, or how much you have changed the world, or how much you have delighted someone, or what impact that has, or even the right book to the right person at the right time can change generations. Even if it seems small, it might not be. Yeah, I know. Man. God.

It’s so terrifying.

Lisa: It can be so terrifying that you can express yourself so painstakingly and that it wouldn’t even get out there.

Craig: Also you can be so insanely vulnerable. You’re putting your beating heart…

Lisa: [laughs]

Craig: basically on the…you’re putting it on the world stage, and you’re saying, “Hey, if anyone wants to come over here, I have a pile of axes…”

Lisa: And trample.

Craig: like if you want to chop up my beating, vulnerable heart, like come on." Of course that’s what happens to a lot of things.

Watching your book go from those excerpts where obviously the tech world looks at it and goes what’s this? The story about Jobs, and Bono, and the provenance of the Lisa name for the computer, and things like that, going from that to getting the thoughtful reviews to getting now in the last, we’re at the end of 2018 now, in the last month or so ending up on all these best of top 10 lists.

Lisa: I know. I can’t even believe it. I can’t even believe it. I haven’t read any of the reviews by the way. I haven’t read a single review.

That’s very smart.

Lisa: My husband has been great. He’ll sometimes read me snippets, or he’ll say, “Oh, it was a good review for the book, but I don’t think you’d like the way they took it.”

I didn’t want to read the reviews at all because I just had a baby and the idea of going on some roller coaster didn’t sound good. I don’t like roller coasters anyway. I have a responsibility to keep my equanimity.

I think that some of the reviews have been quite positive, but if I were to read them, I would hit the roof because they are drawing conclusions about my life from my book that they find unassailable that are not my conclusions.

Craig: Also we’re programed in such a way as, especially when it comes to things like this where it is us as much as it can be us on the page, we are programed to ignore all of the positive and pick up on the one-one billionth of a millimeter of negative. [laughs]

Lisa: Why is that? Why is that? Why could that programing be advantageous? I know. Why is that?

Craig: We’re all broken. That’s why. We’re all suffering from impostor syndrome. We’re all worried we’re going to be caught at any moment, and the curtain’s going to be lifted, and we’re going to be revealed for the frauds that we are.

Lisa: Actually this whole process, it’s felt like it’s happening to someone else. Sometimes I think it’d be nice if I could be more receptive to the good things. I’m not exactly sure how to take them. It feels very detached, but I feel happy for the book. I feel actually relieved because I didn’t really fully consider what it might be like to be savaged when I also had a little baby.

I think I would have just ignored it just as I did, and we would have just ignored it all the more. That would have been really hard.

With any large, creative project, there is so much terror along the way, and it’s so gut wrenching. If it’s not, maybe it’s not working. At least that’s from my very limited experience.

, which is basically you’ve been beaten into a lullaby peace, things are too peaceful. A lot of the post-war generation…

Lisa: Complacency.

. You guys don’t have the…We had to scrounge for rice.

Lisa: You don’t have the fire in your belly.

Craig: Yeah, or the fire in your city to motivate you. There’s totally a truth to that.

Lisa: We spend our lives just so much trying to get comfortable. That’s the last thing that matters to the soul. On your deathbed, the last thing you might say is maybe I didn’t love or I didn’t work, but I was comfortable. I don’t think you’d say that. I think what you want to know on your deathbed is nothing about comfort.

It’s something like did I love the people I loved? Did I really love the people I loved? Did I do the work that I felt meant to do, not someone else’s work but my work. Those two things don’t have anything to do with sheet thread count, or how comfortable you are, or how big your house is, or anything. It’s so strange that these things are at odds.

Craig: Comfort is, you could think of a definition of it as being avoiding anxiety. We spend so much time avoiding things that will make us anxious or avoiding stressful situations. Part of why this book feels so powerful and it’s resonated in the way it’s resonated is that this whole book is a big leaning into anxiety.

Lisa: I know. It was like if I didn’t lean in, I wasn’t going to get out. I had to go all the way in. Sometimes I didn’t know if I would ever get out.

Craig: You feel that. For me one of the most powerful things about the book was getting in the head of a young girl in a way that I realized I just hadn’t. I’d never had that framing before obviously. I wasn’t a young girl. I have lots of friends with daughters, and I play a role in a lot of their lives as uncles, and godfathers, and things like that.

It was just so powerful to read these details that stood out that I wouldn’t have expected in that, in your revealing of them made me realize that oh my god, this is from a very vulnerable place.

You had this moment where Steve gave you some attention or something and you said, “My heart beat like a bird’s heart quick and light in my chest. It was what I wanted, all his attention focused on me all at once.” In another moment you write, “How close are you supposed to be with your father? I wanted to collapse into him, to be inseparable.”

Lines like that and moments like that where I felt like I was learning something and I was experiencing something truly new in the best possible way that only a book can let you experience.

Lisa: I was talking with my friend who’s a father today, with Phillip Lopate actually. We had a coffee, and he was saying, we were talking about fathers and daughters, and I have the sense that like many people have a sense that I’m terribly unique with my father-daughter relationship. It’s unique in its unfulfilled aspects.

I think actually there’s something at the core – I’m probably just repeating Freud and telling myself that I’m original – but I think that there is something at the core of the father-daughter relationship that is unfulfilled. It’s hard to find another person who can love you so dearly and so completely in that way. Then you have to grow up yourself, and you have to go find your own people.

I don’t think it’s just me. It must not be just me, this feeling of it’s not enough. It’s not enough. It gets so close to being just so incredibly right and then it falls away again. Of course this is a more dramatic version of that in some ways, but in some ways it’s not.

Craig: The stuff with Steve and Steve being who he was was interesting just in the sense of there’s only one person in the world that could write about him from that point of view which you had, but the more general qualities of that connection were incredibly universal. People struggle with this even in families where the father is living with them.

Lisa: This is what I’m saying. People struggle with this even where the father’s relationship with the children is quite good.

Craig: Totally.

Lisa: Where it gets close but is never…It cannot be fully completed because it doesn’t have forward motion to it. My mother says, she used to say when I was complaining about my childhood, “Uh, no one survives childhood. They just grow up.”

Craig: Right. [laughs]

Lisa: There’s another phrase about artistic projects which is no project or no artistic work is ever finished. It’s just abandoned. There is this quality of out of your childhood you don’t tie it up into a bow. It’s not complete. There’s always this longing or existential gap.

Craig: There’s always more work to be done.

Still I find myself now that this book is done thinking, “Oh god, it’s done.” I want to just cozy up here forever, but at some point, it’ll be important to get uncomfortable again.

Craig: For me reading this, it was emotional experience for a lot of reasons, but it was also a weirdly physical experience. The book opens with you stealing stuff, grabbing the lipstick and things like that. The reality is I was literally two blocks away from you when you were doing that.

Lisa: What?

Craig: I was living on Santa Rita.

Lisa: You were living on Santa Rita?

Craig: Yes.

Lisa: No.

Craig: Yes. Yes, I was living on Santa Rita, two blocks from that Waverley corner. I moved there in 2010 to work with FlipWord. I ended up living there two blocks from that house for three years. Steve passed away right in the middle of when I was living there, about a year after I moved there. I was walking by that house all the time. I walked by the house on the way to work.

Lisa: You’re like and who is that strange girl nicking things.

Craig: I was like that woman looks like she would be stealing stuff.

Lisa: [laughs]

Craig: It was so surreal for me to read this because…

Lisa: You felt yourself in the place.

Craig: I felt myself there but also it was unpeeling all these questions I had for three years of I wonder what’s going on in there.

Lisa: What’s happening in that house. [laughs]

Craig: It really is this weird, unassuming hobbit’s house on the corner.

Lisa: It’s so beautiful, that house.

Craig: It’s so cool, but it’s not a crazy, giant mansion with machine guns and lasers outside either. It’s just there.

Lisa: It’s wonderful.

Craig: It’s just there. That adds more to the mystery to it. You’re just walking by going, “What’s really happening in there.” It was just this very strange, surreal sense of living in that old Palo Alto area. It was all like Larry and Sergey from Google live there, and Paul Graham is there. It was just weird.

Lisa: That’s so funny because when I was living there, not visiting but living, there was no Google.

Craig: Right. [laughs]

Lisa: All those people weren’t living there.

Craig: Now it’s basically like Disneyland of, startup Disneyland or something.

Lisa: I know. I feel like the Palo Alto City Council maybe was a little behind on setting up regulations.

Craig: Maybe. [laughs]

Lisa: Part of the beauty of the town was all these wonderful, fairly small houses that were all different from each other. To let people tear them down to build compounds, it perhaps was a mistake and cannot be rectified now.

Craig: I moved there totally by chance, knowing nothing. It just so happened a couple friends of mine found a house that at that time in 2010 was still not that expensive. It was three of us, we paid less than a thousand bucks each for rent there.

Lisa: Wow.

Craig: Which is insane to think now. It just so happened to be in the middle of all that I fell backwards into a really beautiful grove. Old Palo Alto is gorgeous. As I’m reading the book, I can picture all of this.

Also even the hills and those drives, there’s this moment where you and your father are driving in his Porsche in the hills up behind Sand Hill Road and up in Woodside.

Lisa: It’s so beautiful there, isn’t it?

There was this…

Lisa: You haven’t been in those hills unless you’ve been in that Porsche.

Craig: Right. You need…

Lisa: No, I’m kidding. [laughs]

Craig: You need that old Porsche or it’s not real. There’s this weird synchronicity of the reading experience and my own experience. Also I’m adopted, and so what was fascinating to…

Lisa: You are. I didn’t know that.

Craig: Yeah. What was fascinating about reading this was just how so much of your book was about the lines of who is in or out of family. When are you allowed in and how much of a struggle that can be even with the blood connection, and also in a weird way how the blood justifies it.

There were these moments where Steve would say things about you, just about your DNA, the DNA connection, the pride in the DNA connection.

Lisa: Then other times that he didn’t believe in genetics.

Right.

Lisa: There was definitely a tussle there. He would come out quite stridently on both sides. Even after we were connected definitively, pretty definitively, the most definitively we could be at the time with the DNA test and even after, he’d notice that we looked similar. Still there was a way he was pushing me away. I was desperately trying to be comfortable in a place of belonging.

If I can’t belong there, can I belong because I construct my own story so much and understand my own story so well that I don’t feel like I can at least be pushed out of that. I felt like the deeper I got into my own story the more it became universal in the sense that it had the kind of arc that stories have, beginning, middles, ends, searching, no resolution, resolution.

The only resolution to the question of belonging is that in order to get this book to a place where it felt like I was honest, I felt more comfortable in my own skin. In that sense, it didn’t matter if I was pushed out of some other group because I felt OK with who I was.

That was the search. That’s what was the impetus for this book was to not feel so badly anymore. Everything was worth that, all public vulnerability, all shameful moments. That does make you question belonging and think about how powerful that is.

Craig: It’s so scary how powerful it is. This book, in your vulnerability and your going to that place, and asking these questions, and creating that arc, gives a lot of other people permission to explore that.

Lisa: Books make you feel sometimes less lonely in your loneliness. They don’t eradicate the loneliness, and they don’t make it go away, but they change its tenor. Of course I hope to change the tenor of some people’s feelings about themselves because I changed my own.

Craig: That’s true. Your father’s celebrity, you shifted it from cliché to huge asset in this book. Because…

Craig: Yeah. Like you said the worry is that it becomes cliché, right?

Lisa: Right.

Craig: What happened in this book because the story was not about that, it wasn’t about his work or whatever, it was about that relationship, and it was about the complexity and the conflict of that relationship.

The reason the celebrity was an asset is because the outward persona of that person was so confident and so knowing, just I know what thing, I know what this thing has to do. I know how this has to work. I know how this should be designed. Then to see…

Lisa: So often right.

Craig: Absolutely right, but what’s often missed in that narrative is the messiness of getting to that rightness.

Because the persona is so strongly confident that to see someone like that struggle with something so fundamental as being present for his daughter was hopeful in a way, because it makes you realize [laughs] that he of all the people who seem to have the strongest sense of movement in the world, still this is so messy. It is so emotionally messy.

Like you just said, not knowing is OK. Not knowing, “How do I be a dad? How do I take my daughter roller skating? Like what am I supposed to say to her? Am I supposed to…Should I be making out with my [laughs] girlfriend in front of her like…

Lisa: It was so valuable to do this book for things like that. There were revelations for things like that. When I looked back without really thinking about it, there were a lot of long awkward silences, and maybe I had thought as a girl that he didn’t want to talk to me, and maybe I thought as an adult that he didn’t care to talk to me or didn’t like to talk.

It wasn’t until I spent the time thinking about it that I realized he was younger than I am now, and he might not have known how to talk to a kid.

Craig: Totally.

Lisa: He was awkward and that he was ambivalent, and that that ambivalence didn’t have anything to do with me and might have had to do with him. Then I’m looking at another person with much more compassion, and I get to have a new relationship with my father and with myself as a girl.

If you change your perspective of your own past, your future changes in some ways. I think there were a bunch of places where I had assumed I know what something meant, and it had become fixed in my mind, maybe even from my childhood perspective.

It was only digging under the skin of it with the perspective of an adult that I was able to realize [laughs] that many of the things I had understood were just incorrect, that there was more confusion and not knowing in a situation than you imagine when you’re a kid.

The confusion doesn’t hurt so much. It’s intriguing and it makes you curious. If someone is malicious, you feel badly. If someone doesn’t want you, you feel badly, but if they don’t know what they’re doing and they’re trying, it changes your perspective of them.

It has been interesting from what I’ve heard, “She doesn’t understand she’s in an abusive situation, or she doesn’t understand her own story.” I think that’s probably true for parts.

One thing I’ve wanted to say was, “No, I’m the person that wrote the scenes that made you feel that way.” [laughs] I might not be telling you what to think. I’m the one who’s making you feel, so don’t think I don’t know what I’m doing.

[laughter]

Lisa: I put those scenes in. There were many scenes. I chose those.

Craig: To tie it back to the cover, the feeling that I got reading this, and maybe my perspective is unique because, like I said, I am adopted. I don’t know any of my blood family. I’ve never known genetic connection to someone.

I lean very heavily on this idea of fluidity in family and how friends can be absolutely fooled into family, and that there’s no difference in the end. Reading this book left me with a sense of hope. It wasn’t a dark book at all, to me.

Lisa: Oh, good. I’m so glad.

Craig: It’s a hopeful portrait of how hard it is. It’s so freaking hard to believe in connections, even when they’re explicit.

Lisa: It can be perilous. People are trying to protect themselves from such dangers sometimes.

We’re so hungry for black-and-white concrete answers.

Lisa: Complexity doesn’t stop connection.

Craig: No. Connection is not either an on or off switch. It’s not binary. There’s insane, crazy, heart-wrenching gradients of connection over the course of your life. It’s going to wax and wane between all different people. It’s constantly modulating. I think I also felt your catharsis in having produced this artifact, which I don’t know if is true or not.

When I finished the book I thought, “OK, this was not only really important for me to read for a bunch of reasons, but this was clearly super important for Lisa to write.”

Lisa: It was so important.

Craig: You feel that.

Lisa: It had jewels all along the way. I hope it will be a book that I’m happy with in 10 years and in 20 years. Obviously, you would write a different memoir at different decades of your life. I’m so glad I didn’t publish the one I would’ve written in my 20s.

[laughter]

Lisa: I’m, like, “Ha.” It took me a decade to be the person I needed to be to finish this one. I had to grow up while I was writing because the perspective of the woman who started writing this book wouldn’t have worked. It was cathartic because there were so many realizations, revelations, and new understandings that cast different light on my story.

Also, just fitting your own story into the arc of traditional narrative is incredible. Maybe, also, you find you belong there, or you find connection there that you a part of this. There must be something about the story that is deeper and more hardwired. That a story, if you get really honest about it, starts to look more universal.

There’s something consoling and comforting about belonging to humanity in that way. It’s comforting in an existential way, not just in a personal way, that you’re not so alone in your most alone moments.

Craig: I’ve experienced this as well where someone who was part of your life passes away, and you maybe have a bunch of unresolved stuff with that person, and you write about it. In doing so, you unlock this whole new conversation. The cruel irony of it is that after having completed that writing…

Lisa: They’re not there to talk about it.

…they’re not there to talk about it. You’re, like, “Oh, my God, if only I could’ve been here when they were still around, the things I would’ve talked to them about.”

Lisa: I did have a few moments of that before my father died because I’d already started thinking about certain things. To whatever extent, I’d started thinking. It was actually helpful. I thought, “Oh, that changes it. I see him slightly differently and better. We can talk a little more.” He seemed to respond to it well.

Yeah, of course, I think, “Oh, that would be fun if we could talk about what I think I learned and you could tell me where I’m totally wrong and where I’m not, from your perspective.” Mostly, now, because I have a baby, I think, “Oh, you missed out. Darn. He would’ve liked this part.”

Craig: I think the cover, the type, the girl…

Lisa: [laughs]

Craig: with the flowers…

Craig: The flowers up here, a bunch obviously, flower children and things like that, but also your couch and I think your chair both had flowers.

Lisa: It’s true that couch and that chair had flowers. The couch and the chair were more abstract flowers, because you can imagine were more hideous, were hideous.

This is beautiful.

Lisa: It’s another example of where…It’s connected to my book now, but the cover art was its own separate creative process. The flowers were not my invention, but I like them. The outline, my mother said, “Is that you? That must be you. I know that looks exactly like you, and you were 12 or so.” I said, “Mom, that’s not me. I think that’s a stock outline of a girl.” I didn’t wear knee socks. I would have liked to but I didn’t.

Craig: It just speaks to how much we project onto things, you know?

Lisa: I know it does, right?

Craig: The cover is connected to the inerts of the book. As a whole package it really is a truly satisfying and successful literary exploration of family and the complexities of it in life, and just how as much as we want to think we know what we’re doing, we don’t.

[laughs] That’s OK, and actually the process of getting to the place of knowing is messy. I feel like this book gives a lot of permission.

Lisa: Thank you so much.

Craig: I’m really grateful that you pushed through, because I know there are always points in the genesis of a book where you’re like, “OK. I’m going to give up on this thing.”

Lisa: Yeah, like every day.

[laughter]

Craig: Every morning.

Lisa: You would know, you know.

Craig: Yeah, just what a gift.

Lisa: Thank you so much.

What a great cover.

Thank you. Thank you so much, and thank you so much for having me.

Craig: Absolutely, my pleasure. Thank you, Lisa.

Lisa: Thanks.

Craig: Hey! You still there? Thanks for listening. As always, the full transcript of this episode lives on craigmod.com.

This episode is kind of special episode, because it’s the first episode I can say was sponsored by you, those readers and listeners out there part of my newly formed, as of 2019, SPECIAL PROJECTS. On Margins is funded and produced entirely by me, Craig Mod. If you enjoyed this episode and others and want to see more of this in the world, consider joining the Explorers Club.

More info on craigmod.com/membership.

If you don’t have the means to support with membership, consider popping on over to iTunes and leaving a review. It would mean a lot to me.

Also, a big thanks to our other sponsor today, blood.

Not red blood cells. Beautiful may they be, colored by hemoglobin, transporting oxygen and nutrients, metabolic waste, body grunts five-million-per-microliter pillow doughnuts when electron scanned, round, delicious-looking little nubs filled to the brim with life particulate, but without nuclei, and therefore, no … no, they have no DNA.

When we speak of blood, B-L-O-O-D, of ties of blood, of being connected by blood, we are speaking of not red, but white blood cells. The sprinkle covered Jujubes of blood. Well-formed nuclei, protectors of the body, carriers of our … code.

Thank you, white blood cells, although sometimes you can make things a little more complicated … than need be.

On Margins is a podcast about making books, hosted by Craig Mod.

Subscribe on iTunes, Overcast, Google Play, Spotify, and good ol’ RSS.