Software is

the Future of Photography

Software ate the camera, but freed the photograph.

Technical notes on our shift to ever-increasingly networked lenses

Craig Mod, January 2014

“I was impressed, but impressed in the way that one might be to a dog that can talk. Not so much for what it has to say, but that it can talk at all.” — Michael Reichmann on the Nikon D1, 1999

Chomp

Boy, oh boy, is software ever hungry. It’s eating everything. The world, most famously, but also books, CDs, DVDs, and now cameras, too. Or, so I propose in my recent The New Yorker article, “Goodbye, Cameras.”

The piece was originally titled the subtly more intimate, “Cameras, Goodbye.” It's meant to be a eulogy for a relationship with an old friend that had largely ended, but the end of which I had yet to fully acknowledge. Because, in short: I love cameras a whole lot, but I love photography even more. And in an effort to explore what the networked lens means for photography, I seemed to have largely, unknowingly, left cameras behind. Could a smartphone really be the best photographic tool for me? This question was both frightening and intriguing.

My love for cameras — as objets de désir — hasn't and will never completely wane. I get far too excited following camera news, and dpreview.com feels not unlike an infinite Christmas tree. But, the point of “Goodbye, Cameras” was to articulate something deeply personal I felt welling up inside of me as a someone connected to photography, technology, and image making. As someone who cares about telling stories alongside pictures.

So, if you’re interested in this topic — please join me. I'd like to dive into more technical detail here than seemed prudent in “Goodbye, Cameras.” I'd like to poke deeper into the idea of the network and its implications on the photograph and photography, more precisely define photography’s role in my life, ponder digital archives, and layout some thoughts on dealing with technological sea change. You know, just a few light topics.

Because while our relationship with so-called traditional cameras is fading, there’s never been a more interesting and, indeed, complicated, time to be involved with the photograph.

The convergence

In “Goodbye, Cameras” I wrote:

After two and a half years, the GF1 was replaced by the slightly improved Panasonic GX1, which I brought on the six-day Kumano Kodo hike in October. During the trip, I alternated between shooting with it and an iPhone 5. After importing the results into Lightroom, Adobe’s photo-development software, it was difficult to distinguish the GX1’s photos from the iPhone 5’s.

The iPhone 5’s images hadn't yet risen to the level of the GX1’s images, but a shocking convergence was undeniable. Furthermore, I found myself pulling more and more magic out of my iPhone than I previously thought possible.

Four years ago, when I set off for Annapurna Base Camp with my GF1, there was no question: the GF1 was leagues above the then iPhone 3GS in terms of image quality. I took not one single photo with the 3GS. Here, in stark contrast, I sat in Lightroom and was hard pressed to say the GX1 was significantly better than the year and half old iPhone 5. And even then, it was very often a wash. This paralleled my experience in Nepal regarding my dSLR and the GF1 — the GF1 was good enough. But most importantly, the GF1 brought with it enough value in simplicity and usability to displace the quality disparity between it and the dSLR.

This was the ah-ha! moment — as a traveling photography instrument, my iPhone 5 was doing to my GX1 what my GF1 did to my dSLR.

I then concluded with what I took to be a rather obvious statement:

… it seems clear that in a couple of years, with an iPhone 6S in our pockets, it will be nearly impossible to justify taking a dedicated camera on trips like the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage.

An aside: So close, RX1

I had the pleasure of trying out a friend’s RX1 (where all these Xs and 1s come from, I know not) last February. Needless to say — I was smitten. In an early draft of “Goodbye, Cameras” I had written the following:

The RX1 is beautiful. Stunning. An ideal of what Panasonic set out to achieve — but fell short of — with its GF1. The RX1 is solidly built with a single, fixed focal length. No zoom. No interchangeable lenses. Just a full-framed, professional grade, pocketable camera with an uncompromising point of view. But at nearly $2,800.00 USD, it’s far from cheap or very consumer friendly. Still, how I have lusted for it. More than the Leica M Monochrom (no matter how hard I try to convince myself, I simply can not justify that Leica price tag).

The RX1 though — my mouse-cursor has hovered above the Amazon one-click purchase button enough times to send shivers down the spines of AmEx executives. But, yet, I’ve never pulled the trigger.

My inability to buy that camera — to come up with a justification for how it was better than my GX1 — shook me up. All of my photographic fetish senses were on fire, and yet, could I really not find the value proposition in what Sony had on offer?

Archival what?

“I say there is no species of technology that have ever gone globally extinct on this planet.” — Kevin Kelly

A general — and now obvious[2] — rule for the digitization of any medium is that analog will always have a place, however niche. There is an undeniable warmth of listening to vinyl, just as there is a paper-aware rhythm to sentences pulled from a typewriter, just as reading a beautifully produced physical book will — as a pure reading experience — beat out a glaring iPad screen, just as, of course, taking pictures with mechanical cameras or printing in a darkroom will be meditative in ways a networked lens will never be.

For those who print, pixel data is everything. For those who live and die by the screen, the cap on useful pixel data is actually quite low. Around ten megapixels,[3] if that. Of course, more megapixels means more cropping opportunities, but it also means larger files.

In dropping the need for ultra high-resolution pixel data, what is gained? What’s lost?

In thinking about this, a question I was drawn back to time and time again was: What constitutes an archive? What makes something so-called “archival quality?” Large format photographers laugh at dSLR or micro four-thirds pixel data. Just as dSLR aficionados laugh at the notion of a smartphone as producing archival data. Where are the real lines drawn? What defines the scope of the kinds of data that should be — and could be — included within the idea of an archive?

These questions, of course, span all disciplines. Harvard held a conference focused on digital archives related to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. Kyle Parry, writing for Contents Magazine, sums up how the Japan Disaster Archive “expands, or even violates, the accepted bounds of the archive.”

For a start, it stores almost nothing. Instead, it is networked: nearly all of its over 1 million items—documents, websites, tweets, images, audio, video—are not actually held on Harvard’s servers. They come instead from a federation of “content partners” like Yahoo! Japan and the Internet Archive. The archive is also “participatory.” It provides its users with the means to annotate and geo-locate items and enables them to build “collections.” These collections can either stand on their own or form the basis for multimedia interactive narratives.

Limiting the scope to photography, I wrote in “Goodbye, Cameras:”

While we’ve long obsessed over the size of the film and image sensors, today we mainly view photos on networked screens—often tiny ones, regardless of how the image was captured—and networked photography provides access to forms of data that go beyond pixels. This information, like location, weather, or even radiation levels, can transform an otherwise innocuous photo of an empty field near Fukushima into an entirely different object. If you begin considering emerging self-metrics that measure, for example, your routes through cities, fitness level, social status, and state of mind (think Foursquare, Nike+, Facebook, and Twitter), you realize that there is a compelling universe of information waiting to be pinned to the back of each image.

As more images touch the network, and as the information orbiting those images becomes more compelling, the archival value of the standalone picture as a social artifact — no matter the megapixels — will continue to diminish. If you view photography as a medium of record, then it’s hard to overvalue this shift.

Once you start thinking of a photograph in those holistic terms, the data quality of stand-alone cameras, no matter how vast their bounty of pixels, seems strangely impoverished. They no longer capture the whole picture.

In fact, photography itself begins to split into two entirely different beasts: the networked image laden with metadata but possibly lower pixel density, and the silver gelatin print, a static, hidden artifact of high visual value.

The value of discomfort in the march forward

My favorite place from which to ponder technological change is personal experience. Practice grounds thinking to reality. And with that grounding comes the greatest chance to illuminate the near-now for those others who also love something, but perhaps can't see changes imminent.

I try to keep a sensitive heart about these matters.

When I felt certain inevitable shifts in books, I wrote “Books in the Age of the iPad.” When micro four-thirds blew my hat off, I published the “GF1 Field-Test.” As I finished a Kickstarter campaign with co-author Ashley Rawlings for “Art Space Tokyo,” I wrote up the experience in “Kickstartup.” As simplicity found its way into iPad publishing, I published “Subcompact Publishing.” And after finishing work on Flipboard for iPhone, I made “Flipboard for iPhone, the Book” to help us think about the value of giving form to the formless.

All of these pieces teeter on the edge of a slope leading away from some incumbent mode of thinking — physical only publishing, SLR based photography, traditional publishing, clunky magazines as apps — towards a new mode — digital and physical hybrids, smaller mirror-less photography, sustainable self-publishing, simple and light tablet publishing.

Those invested in the old will rightfully take issue with the new. Because anyone who loves and has invested in a way of doing something will not — and should not — give it up without good cause. But that doesn't mean the changes aren't real.

What’s fun about straddling these technological shifts is that it automatically places you in an uncomfortable position. This is exactly where you want to be though, because discomfort is where potential lives. Potential rarely rests on a chaise lounge by the beach. Potential almost never lives in the systems cradled by the incumbents.

In fact, discomfort and change go hand-in-hand. That’s why there are those able to extract crazy, seemingly unfair wealth from change — they’re willing to postulate and endure great discomfort (high-risk) for potential payouts. They look forward, objectively beyond nostalgia.[4] It’s not magic. They’re just not complacent.

So when I wrote that we’re saying, have said, or will soon say, Goodbye (depending on who you are), to cameras, I was writing from that place of discomfort, but was also simultaneously filled with a budding curiosity. Because part of me would much rather be on the beach with my Hasselblad. And, certainly I don't want to say goodbye to that, not really. Why would I? They’re wonderful machines. Machines with which I share a storied and intimate history. And the beach is really nice. But, I have to step back and ask myself two things:

- What greater photographic potential lives within this discomfort?[5] And, more importantly …

- To what service do I create images?

Rather than dismiss the discomfort, I find it more rewarding to look within it for nourishment and some unexpected delight.

Phototrope: All story

Photography, for me, has always been about story. Has always been about placing markers in my mind to which to later return. It was, long ago, about obsessing over the mechanics of process and geekery, the zone system, about perfect black and white saturation and gradients. But that period was short. And throughout the years, I’ve found myself returning to — with each tick of my photographic journey, each incremental tick of technology — the story. The who, what, when, where, why, and how of the thing before the lens. And how capturing that image would inform some future version of my self, or, god willing, something larger.

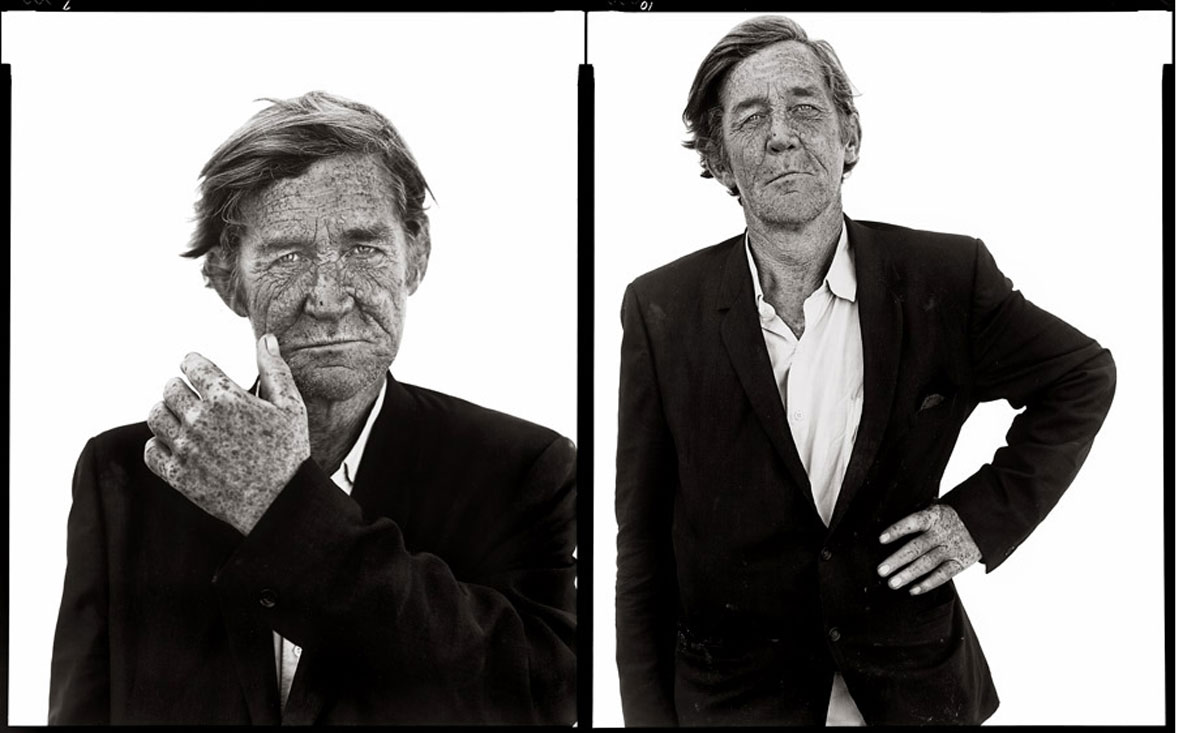

Avedon

I return again and again to Avedon’s portraits, not because they’re beautifully exposed (though they are) or because he used large format film, but because within each face lives branched lives, alternate universes. And I get lost in those universes. They speak to me, are full of myth — pull me in and demand attention like a bracing short story.

But the most poignant or moving, certainly most intimate, of all of Richard’s images are those of his father. Made more powerful because of the following letter and story accompanying them:

Dear Dad,

I’m putting this in a letter because phone calls have a way of disappearing in the whatever it is. I’m trying to put into words what I feel most deeply, not just about you, but about my work and the years of undefinable father and son between us. I’ve never understood why I’ve saved the best that’s in me for strangers like Stravinsky and not for my own father.

There was a picture of you on the piano that I saw every day when I was growing up. It was by the Bachrach studio and heavily retouched and we all used to call it “Smilin’ Jack Avedon”—it was a family joke, because it was a photograph of a man we never saw, and of a man I never knew. Years later, Bachrach did an advertisement with me—Richard Avedon, Photographer—as a subject. Their photograph of me was the same as the photograph of you. We were up on the same piano, where neither of us had ever lived.

I am trying to do something else. When you pose for a photograph, it’s behind a smile that isn’t yours. You are angry and hungry and alive. What I value in you is that intensity. I want to make portraits as intense as people. I want your intensity to pass into me, go through the camera and become a recognition to a stranger. I love your ambition and your capacity for disappointment, and that’s still as alive in you as it has ever been.

Do you remember you tried to show me how to ride a bicycle, when I was nine years old? You had come up to New Hampshire for the weekend, I think, in the summer when we were there on vacation, and you were wearing your business suit. You were showing me how to ride a bike, and you fell and I saw your face then. I remember the expression on your face when you fell. I had my box Brownie with me, and I took the picture.

I’m not making myself clear. Do you understand?

Love, Dick

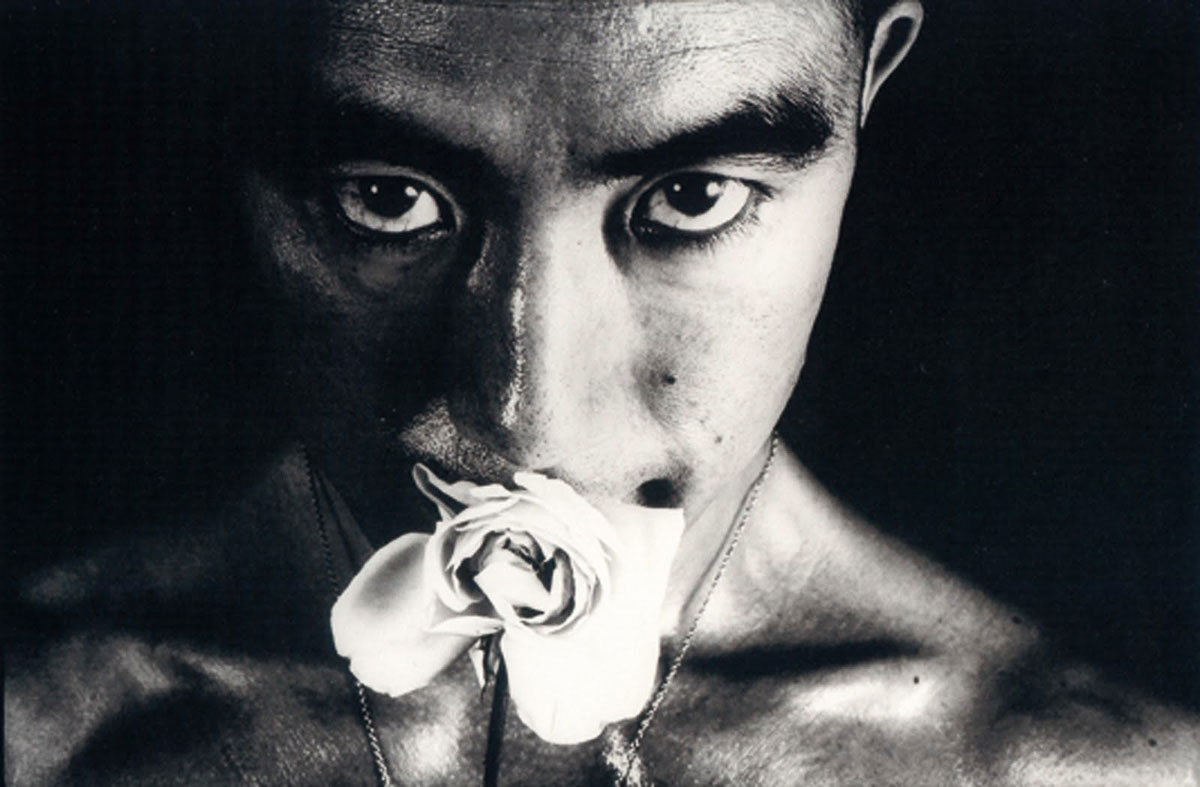

Hosoe

I return to Hosoe and his portraits of Mishima. To be privy to such an intimate relationship with that powerful, complicated artist, and then share with us that access is truly a gift. The fact that the images were beautifully exposed and black and white is secondary to that greater story. And, indeed, it's atop that greater story on which these images live and die.

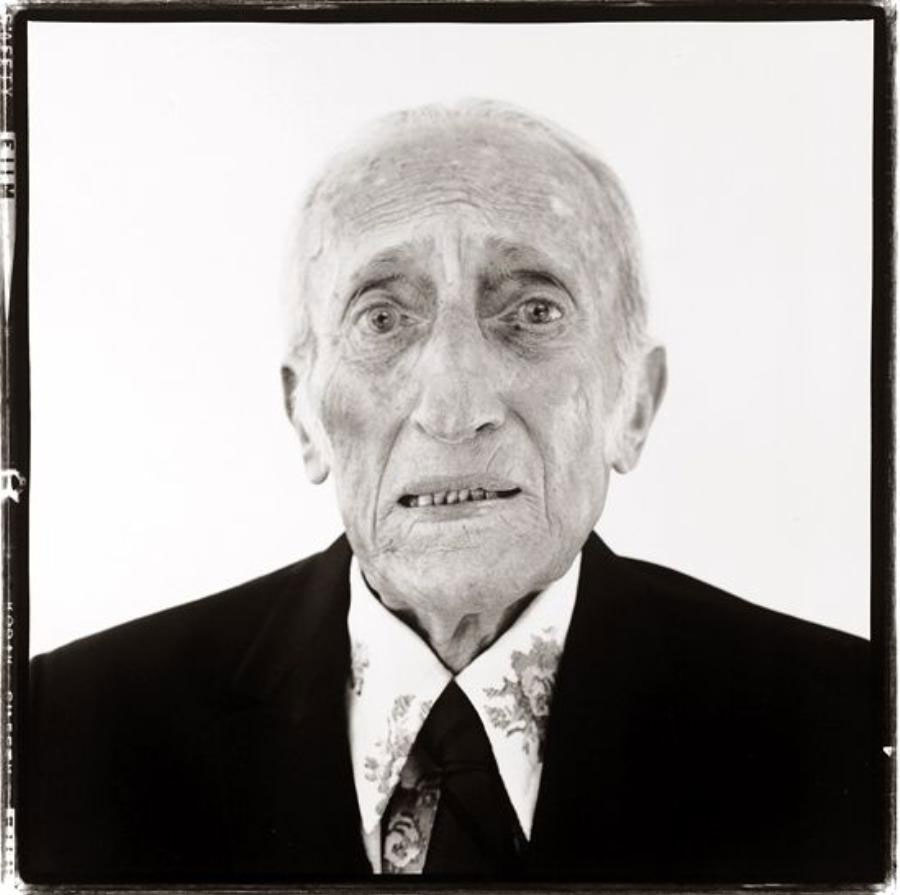

Toledano

I return to Phil Toledano and the images of his father.[6] They bring me back to my own images of my late grandmother, shot with some random medium format device I borrowed from a friend, in my attempt to capture the last few moments of her life as she was pulled under and made increasingly incoherent by the dark tide of Parkinson’s Disease.

In those moments the machine did not matter one bit. And I am grateful — indeed, I owe so much — to those images for helping me and my family better understand just what was happening, however fleeting, inside of a mind made impenetrable by disease.

This is my lens: Moments, memory, story, beauty. Basically in that order. Humor is also in there, above beauty. Beauty has some intrinsic value, but, in my opinion, beauty shrouded in thin story is not worth as much as great story encased in the dregs of the world.[7] Story, for me, gives purpose to the beauty.

This is why Cartier-Bresson can take blurry masterpieces (although this was greatly, hilariously, mortifyingly debated by the Flickr community) — because they are first and foremost story or documentation, and secondly technical achievement.

The shift to a smartphone for photography scares me because I love the boxes. Love their purpose. Their simplicity. So dearly love knowing I’ve captured all that detail. Love their constraints and all the potential packed within them. But in the end, for me, photography has never been about a box. The box was always a means.

Tools and craft

Over the last decade, my rule as a creator — be it as a programmer, writer, designer or photographer — has been to use the simplest possible tool for the job. Use the simplest tool until you breach its potential. If you think you’re using the simplest tool and find one simpler yet, switch to that.

Connected to that rule of simplicity is a bias toward constraint. I’ve always shot with one lens. Obsessed over a single type of film. Worked for years with one type family. One specific CMS. A single scripting language. I am deeply suspicious of technology and find the easiest way to keep from creating is to trick yourself into believing some other tool — just that shiny thing over there — will make all the difference in how you work.

With the endless permutations of lenses and bodies and film types and developing methods, photography has always been a hacker’s playground. So it’s with no small dose of irony that in order to distill the entire spectrum of the photographic process, we’ve had to create one of the most complex pieces of consumer technology ever. Believe me when I say, I approach it with trepidation.

If your relationship to photography revolves around story, and a direct connection to the network implicitly brings with it more who, what, where, when, why, and how, and the smartphone touches the network in the most indigenous, simplest possible way, then the smartphone may be the photographic tool for you.

I say “may” because until this recent trip, I didn't think it could be for me. I had formed biases against the kinds of images possible with a smartphone. In service to story, a certain amount of quality or potential within a tool is inherently necessary. I didn't think that an iPhone had crested the baselines for quality or potential. But when I took a closer look, I realized how wrong I had been.

Most smartphones don't presently handle low-light well, or produce great bokeh, or output high-density, high-quality pixel data. If you're used to the spectacular bokeh of a 50mm f/0.95 Noctilux, then you'll be hard pressed to find value in the cheap lens of a smartphone. But I hesitate to agree that all of these complaints will remain valid for very long.

Five years ago we had no network in the pocket. Now we have full HD video and high-quality image capabilities with us at all times.[8] Five years from now, I would be very surprised if many of the technical complaints — especially those around megapixels, low-light performance, or indeed, even bokeh (update Jan 12, 2014: in-chip selective focus) — remain.

One of the unexpected joys of shooting with my iPhone has been finding out just how much craft exists in a place supposedly bereft of craft. It’s an oddly rigid assessment to assume a smartphone somehow denies craft from the user. In fact, the argument that craft dissipates as modalities simplify or digitize is so old as to be a running joke for any new media practitioner. From physical to digital film editing, from physical to digital graphic design, from anything to the iPad, and from physical to digital photography, we’ve heard it before: Craft is lost!

My belief is is much simpler: craft inhabits whatever medium or tool you work with, if you let it.

What the network means

Being close to the network does not mean being on Facebook, though it can mean that, too. It does not mean pushing low-res images to Instagram, although there’s nothing wrong with that. What the network represents, in my mind, is a sort of ledger of humanity. The great shared mind. An image's distance to it is the difference between contributing or not contributing to that shared ledger.

When the iPod came out, it was decried as “lame” because it wasn't as technically powerful as other mp3 players. But what the iPod did that no other player did — and what, in the end, proved to be the seed set to shift our relationship with music — was minimize the distance between the wanting to carry a lot of music and the doing. iTunes simplified a few steps. Not many, just a few. Just enough to significantly alter that dissonance between the promise of digital music and the application of it. The iPod solved, as many Apple products do, a user experience issue, not tech issue.

Android-based cameras are on the market. There are lens hacks to plop atop our iPhones. But in the end, these are far less elegant solutions than those built into the very devices they are trying to mimic or augment.

The smartphone brings the network close to photographs in a way similar to how the iPod brought digital music closer to our ears. By removing a few steps (bluetooth sync, extra batteries, another device), the smartphone drastically decreases the dissonance between wanting and doing. It’s the simplest lens, at the shortest distance to the network. Regardless, if you look at the arc of technology and the difficulty of interface design, there’s good chance that the iPhone or Nexus camera will overcome their shortcomings more quickly than Nikon will produce an Android-based camera with an easy to use, networked interface. Even smartphone RAW support is soon to come.

The smartphone deceives because it is a tool for the masses. A doodad for posting to Facebook. But for those photographers among us interested in plumbing the depths of the network’s effect on images, it’s a far more serious tool — because it’s so native to the network — than most anything else available today.

The use of the network maps to a sliding scale. Unsurprisingly, this mimics book writing atop the network, too. In much the same way an author can choose to use the network as they wish — from posting chapters serially on Wattpad, or funding a book's production on Kickstarter, or carrying on conversation with readers via Readmill once a book has been published — so, too can a photographer choose their level of engagement.

One extreme of the scale is to post everything you do in real-time to all your social networks. The other extreme is to use the network for the aforementioned data collection, but keep the images close to your chest, and then release them where you see fit, as you see fit. Not unlike what I’ve done with the photographs in this essay. Not unlike how photography has always functioned.

Infinite lenses

There’s another side to this conversation that tends to get overlooked. The most transformative side. It’s the side of accessibility and of giving voice to those hitherto voiceless. For, if you peek into any emerging world — India, Africa, South East Asia — you realize many have never known a camera, and never will. But increasingly they will grow up with a pretty good lens in their phone, and an even better one in just a few years to come. So, yes, the networked lens means selfies — in the same way Twitter means, “Just had some awesome coffee” — but it also carries with it the chance for storytelling on a global stage by those who have never before had that chance.

Software ate the camera, but freed the photograph. It makes me uncomfortable, and if you care about cameras, it should make you uncomfortable, too. But — and here’s the trick — try to see if there isn't something valuable in that discomfort, if it doesn't bring with it a way to look at photography with fresh eyes, with new excitement.

As Richard said: “You are angry and hungry and alive. What I value in you is that intensity.”

You are hungry and angry and alive, indeed. What, of your stories, will we tell? And how will we best tell them?

Cameras, goodbye — sure.

But, photography, hello — you haven't been this exciting in years.

- ---

- It wasn't always obvious. Those on the forefront of change love to think we must throw it all away. That anything outside of the new is soon to be dead. For example, even the book as a format — not just a physical object — was declared weirdly dead in the early 90s: the death of the novel by Hypertext was an actual phrase in academia. There are enough examples now to know that digital doesn't completely obviate analog. Which brings up another corollary of these shifts: We tend to overestimate the death of something, only to return to the supposedly dead thing later, with a greater love, but in far fewer numbers. Maybe, even, with more respect. I know I’ve purchased — much to my surprise — far more physical books in the last year than I'd ever have ever guessed five years ago.↩

- 4K barely needs eleven megapixels: Megapixel calculator.↩

- Without, necessarily, throwing *away* nostalgia. Instagram was successful because it wholly embraced our new modes of capturing and sharing images while bringing with it incredible amounts of filtered nostalgia.↩

- There is always the possibility that there is no value in the networked lens. That it bring with it no service to photography. That it will take over as a fad, and in taking over destroy all that has come before. All film will be lost. All camera equipment melted down into smartphone bodies; lenses ground into shot glasses. Printing equipment will be wrenched from the hands of those who love printing. Books detailing ancient photographic processes will be burned, those processes forgotten. And someday, far into the future, the slightest hint at the craft filled epoch defining classic photography will glint in our review mirrors, and, sure, we'll try to dig it up, try to figure out those chemical mixes once again, but fail. The art having been lost forever. I suppose that’s possible, but probably not likely. The more likely scenario: most photography will be networked, a small amount won't be. And neither the two shall worry about the other one bit. ↩

- Is there a more universally complicated, culturally transcendent relationship than that between father and son? ↩

- Story need not be explicit; in fact you can be as selfish as you need with story. The image can whisper its story to you and you alone and that’s fine.↩

- Super duper privileged pockets.↩