Kickstartup

Successful fundraising with Kickstarter.com

& (re)making Art Space Tokyo

— Craig Mod, July/August 2010

$24,000 in 30 days

a room full of books in 60

& a new way of publishing in 90

Where is publishing heading?

We have Kindles and iPads, iPhones and Androids. Print on demand is cheap — and good. Everyone shops at Amazon.com. Most books are a click away.

Contemporary publishing is engulfed by a forest of question marks. What defines a beautiful book? Is it printed or digital? How much does it take (time, money, energy) to produce? How do you get it to your audience?

There are so many questions because there are presently so many available options. Advancements in affordability of printing, promotion and distribution has significantly lowered the barrier to entry for would-be publishers.

We choose the medium.

We build the audience.

And now, with Kickstarter, we also raise the money.

I want to share with you a story about books, publishing, fundraising and seed capital. It's a story that I hope will change how you think about all of these topics. And it's a story that I hope will serve as a template.

In April 2010, Ashley Rawlings and I used community fundraising to raise nearly $24,000[1] to breathe new life into our book, Art Space Tokyo. My goal here is to outline what we did and why we did it, with the hope of inspiring anyone with an itch, gumption and a good narrative, to do the same. To bring beautiful, well-considered things into the world.

The story begins on March 29, 2010, 10:18pm JST, when a woman sitting in her Brooklyn apartment pushed the first domino. Her $65 pledge kicked off a monthlong fundraising effort that would culminate in a room full of hardcover books, a publishing think tank and the means to begin experimenting with books on the iPad. Oh, and this essay.

The Project: Art Space Tokyo

It starts with a book.

Art Space Tokyo is a book best described as a guide to some of the hidden galleries and museums in the city. Editor and co-author Ashley Rawlings and I put the book together in 2008. It sold out within a year and was never reprinted.

The book is important to us because we put so much work into its production. But it's particularly important to me because over time this project has come to embody much of my ethos towards publishing, printing and the book as an object.

When writing Book in the Age of the iPad,[2] I was largely thinking about Art Space Tokyo. It is a wholly formed literary object — a well-considered balance of editorial, design and physical craft. It's not perfect but I was proud of it when we completed it and I still am.

I spent a good chunk of 2009 thinking about the convergence of digital and analog in the publishing world, and this year (2010) I began to speak publicly and publish articles on the subject. I had spent time treading water in the independent publishing world and thought I might be able to inspire similar folk to reconsider the habits we had fallen into. A lot of us were thinking like mass-market publishers despite being anything but.

In the spring of 2010, a few stars aligned and I was able to buy back the publishing rights to Art Space Tokyo. This was deeply exciting. I saw this as a chance to produce what I had been writing about: a physical book that leverages the advantages of print, and a compilation of varied, definite content [3] (interviews, maps, essays, illustrations, tabular data, and so on) perfect for digital book experimentation.

Once I had obtained the publishing rights, the only question was:

How do we fund this?

The book into which we wanted to breathe new life. Spoiler alert: We succeeded, and you can get a copy here!

Your Fundraising Pal, Kickstarter.com

I wanted to use Kickstarter the moment I heard about it back in mid-2009. For what, precisely, I wasn't yet sure. But that was just a niggling detail — a detail filled by the acquisition of Art Space Tokyo's publishing rights.

Kickstarter.com is a fundraising website. You create an account, describe your project and set a money goal to be obtained within a specific time period. Anyone in the world with an Amazon account can pledge money to help fund your project. Pledges are tiered, with each tier offering different incentives. If your project doesn’t reach your pre-set (unchangeable) monetary goal in the (unchangeable) time limit, nobody pays. If you reach your goal before the time limit, you continue to raise money until the time limit is up. This system has several interesting implications.

Backers simply can't lose — if you can’t complete the project, they don’t pay. And if you can, they get both their tier award and the satisfaction of knowing they were instrumental in seeing your project through to completion.

The seamlessness of this process lies in that Kickstarter uses Amazon for payments. Amazon acts as an escrow service — if pledge goals are met, the pledges are automagically charged the moment the funding time limit is reached.

For those creating projects, there are three points to consider when setting goals:

- figure out the precise minimum scope of what we want to create

- calculate how much money is required to achieve that minimum goal

- And finally, consider the power of our social network. In other words, how much money do we realistically think we can raise?

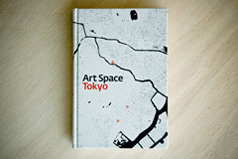

Silkscreening

The slippers are mine. I know this because my name is on them. They put the wrong company name, but I can’t blame them because I had just changed it the day before. Naturally, the slippers are too small and I spend the morning in the warehouse performing that tip-toe dance foreigners in Japan are so familiar with.

The first thing you notice about Mr. Nakamura is his kind eyes. The second is his calm — he's the buddha of silk screening. He and his assistants are endlessly amused that I wanted to come and investigate their facilities, and flattered enough that they give us an hour and half tour. They happily answer all questions as they proudly show off the silk-screening processes in which they specialize.

It’s an impressive facility — they’re able to handle jobs as small as Art Space Tokyo up to highway billboards. They have aircraft hangar sized darkrooms with exposure bulbs looming like miniature suns. And their output is prolific.

Unfortunately, they are adamant that I don't photograph the facilities. Still, I manage to covertly eke out a single photograph — that of Art Space Tokyo covers drying. Covers are hand-printed with care to ensure identical results. Watching this fragile process makes me appreciate even more the miracle that is each of these books.

Mid-tour I wonder aloud if they’ve felt a pinch from ravaged publishing industry. They haven’t, reports Mr. Nakamura. Why? Because even though the publishing world is in turmoil, designers are more than ever turning to special printing processes for covers and posters. Printing processes in which his operation specializes. In fact, he says, we've seen our output increase in recent years.

Whether this is really true or not doesn't matter much to me. The answer still makes me happy that we were able to use Mr. Nakamura’s facilities. All mass market publishing rationale lead away from producing a book with a silk-screened, cloth cover. But Kickstarter allowed us to buck that trend, to ignore the demands of mass market pricing for our niche product, and produce the book that we felt should exist. So I find myself in the bowels of a giant, award-winning, local printer, who in return for our supporting of their efforts showed a warm hospitality, and a deep appreciation for our project.

Micro-seed Capital

I had one chief consideration in defining the goals for the Kickstarter project: make enough books to generate substantial returns. Then use those returns to further expand this or similar publishing endeavors.

I never intended to just sell a few books. The last thing I wanted was for this Kickstarter project to be nothing more than the start and end of Art Space Tokyo’s new print run. Instead, I wanted it to be the jumping point for exploring more projects in a similar spirit to Art Space Tokyo; a means to explore digital books and to fund the startup of a publishing venture that could make this happen.

Which is to say, I saw this as micro-seed capital. To not look at fundraising on Kickstarter from this perspective is to miss out on the site's full potential.

With Kickstarter, people are preordering your idea. Sure, they’re buying something tangible — a CD, a movie, a book, etc — but more than that, they’re pledging money because they believe in you, the creator. If you take the time to extrapolate beyond the obvious low-hanging goals, you can use this money to push the idea — the project — somewhere farther reaching than initially envisaged. And all without giving up any ownership of the idea.

This — micro-seed capital without relinquishment of ownership — is where the latent potential of Kickstarter funding lies.

In His Underwear

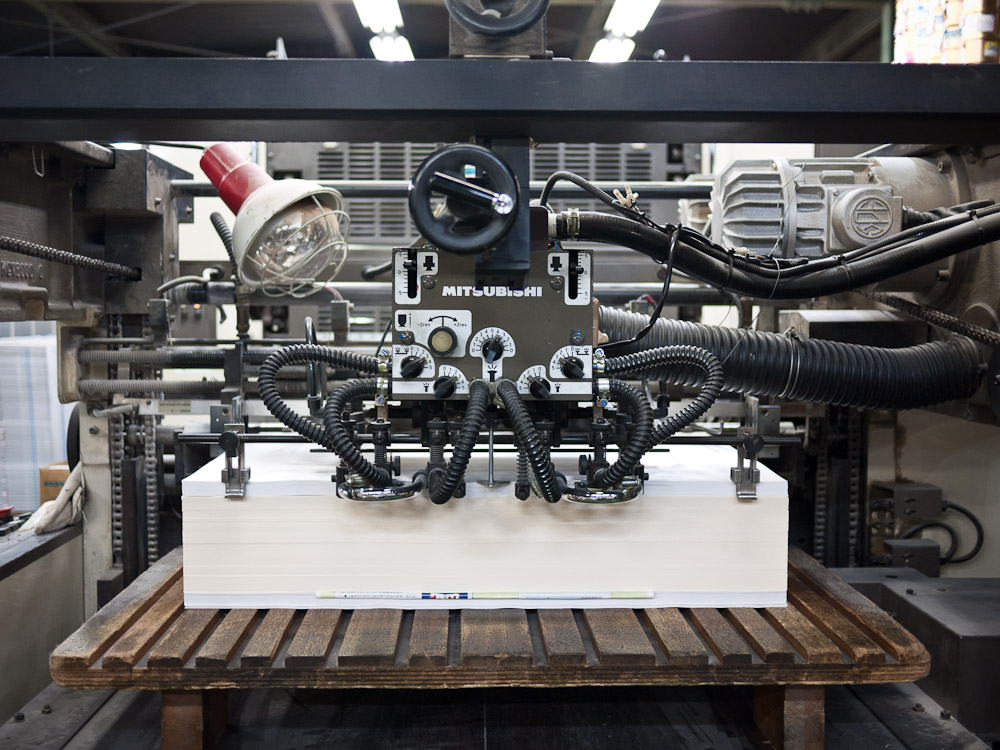

He must be eighty years old, standing there in his underwear with a lit cigarette dangling from his lips. I wave hello and he grins back, lazily manipulating dials and levers on the sprawling printer.

Eight hours in and this is our last stop for the day. The little shop is tucked down an anonymous backstreet in an anonymous apartment block somewhere just west of west-Shinjuku.

The cadre of book facilities coordinating on this project include four printers, a bindery and a stocking & fulfillment group. I’ve visited all the printers today and this — here, incongruously, in a smoke-filled first floor of an apartment complex — is the obi, or belly-band, printer. Their job: one color on cheap paper to be wrapped vertically around the back cover.

An artisanal grittiness pervades the Japanese printing world. The facilities are grimy — well used — and I’m left wondering just how the books are going to come out pristine. But, of course, they do.

A younger fellow with yellow dyed hair and thick glasses wrangles the output of the machine, which is churning out a hundred obis a minute. He slips an ink stained hand into the printing mechanism, pulling out, mid process, a sheet to check the ink spread. Somewhat satisfied he twirls a few more dials and with a wink and wave sends a signal back to Mr. Underwear indicating, "crank up the output!"

Defining the Pledge Tiers

The first step in determining the Art Space Tokyo Kickstarter tiers was to learn from the results of other successful projects. I gathered data for the top 20 to 30 grossing Kickstarter projects as of March 2010. I then mapped out the number of pledges per tier, looking for a balance between number of pledges and overall percentage contribution of funds to my data set. Here is that data with the top five grossing tiers by percentage contribution highlighted in yellow:

| Tier Amount | Pledges | Total $ | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|

| $10,000 | 2 | $20,000 | 5.58% |

| $7,500 | 1 | $7,500 | 2.09% |

| $2,500 | 6 | $15,000.00 | 4.19% |

| $2,000 | 2 | $4,000.00 | 1.12% |

| $1,500 | 1 | $1,500.00 | 0.42% |

| $1,000 | 12 | $12,000.00 | 3.35% |

| $750 | 9 | $6,750.00 | 1.88% |

| $500 | 60 | $30,000.00 | 8.37% |

| $300 | 8 | $2,400.00 | 0.67% |

| $250 | 92 | $23,000.00 | 6.42% |

| $200 | 25 | $5,000.00 | 1.40% |

| $150 | 142 | $21,300.00 | 5.94% |

| $125 | 14 | $1,750.00 | 0.49% |

| $100 | 586 | $58,600.00 | 16.35% |

| $80 | 20 | $1,600.00 | 0.45% |

| $75 | 2 | $150.00 | 0.04% |

| $60 | 40 | $2,400.00 | 0.67% |

| $50 | 1,699 | $84,950.00 | 23.71% |

| $35 | 14 | $490.00 | 0.14% |

| $30 | 489 | $14,670.00 | 4.09% |

| $25 | 1,253 | $31,325.00 | 8.74% |

| $20 | 134 | $2,680.00 | 0.75% |

| $17 | 94 | $1,598.00 | 0.45% |

| $15 | 248 | $3,720.00 | 1.04% |

| $12 | 37 | $444.00 | 0.12% |

| $10 | 352 | $3,520.00 | 0.98% |

| $5 | 391 | $1,955.00 | 0.55% |

| Totals: | 5,733 | $358,302.00 |

This data is, of course, hardly perfect (for example, not every project I looked at used the same tiers). But it's good enough to give us a sense of what price ranges people are comfortable with.

The $50 tier dominates, bringing in almost 25% of all earning. Surprisingly, $100 is a not too distant second at 16%. $25 brings in a healthy chunk too, but the overwhelming conclusion from this data is that people don't mind paying $50 or more for a project they love.

It's also worth contemplating going well beyond $100 into the $250 and $500 tiers: they scored relatively high pledging rates compared to other expensive tiers.

The lower tiers — less than $25 — are so statistically insignificant (barely bringing in a combined 5% of all pledges) that I recommend avoiding them. Of course this depends on your project — perhaps there's a very good reason for a $5 tier. More importantly, this data shows that people like paying $25.

Having too many tiers is very likely to put off supporters. I’ve seen projects with dozens of tiers. Please don't do this. People want to give you money. Don't place them in a paradox of choice scenario! Keep it simple. I’d say that anything more than five realistic tiers is too many.

The average pledge is around $62.50. This amount happened to fall very close to my calculation for the cost of production and shipping for Art Space Tokyo. And it gave me further confidence that setting the price for the book at $65.00 was the right decision.

Taking the above data into consideration, here are the tiers I chose and the corresponding results for the Art Space Tokyo Kickstarter project:

| Tier Amount | Pledges | Total $ | Total % | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $25 | 28 | $700 | 3% | Art Space Tokyo PDF |

| $65 | 155 | $10,075 | 42% | Above + physical book |

| $100 | 64 | $6,400 | 27% | Above + name in book as backer |

| $250 | 11 | $2,750 | 12% | Above + signed book + limited edition tenugui |

| $850 | 4 | $3,400 | 14% | Above + original Nobumasa Takahashi artwork |

| $2,500 | 0 | $0 | 0% | Above + day tour of Tokyo |

| Totals: | 262 | $23,325.00 |

This is a great spread. The $25 tier, while statistically weak, allowed folks who had already purchased the book (in its first edition) to contribute to the project. In a sense, it served more to bolster the community of backers than to provide financial return. This is an important point: you're not just raising money, you're also building a community of supporters through the fundraising process.

No surprises in the other tiers: $65 easily dominated, but we knew it would from our dataset. $100 provided a nice 'upgrade' tier (I suspect that almost all backers who pledged $100 would opted for $65 before considering $250). The $250 tier might have done better had I explained what the tenugui reward was earlier. And $850 was a perfect catchall for lovers of Takahashi-san's work, or those who have the means to give a project such substantial support.

I didn't sell any of my mind blowing bike/café/museum/architectural/culinary Tokyo day tours at my crazy rate of $2,500. But then again, that was there to make Takahashi's print look like a good deal more than turn me into a tour guide.

The body block

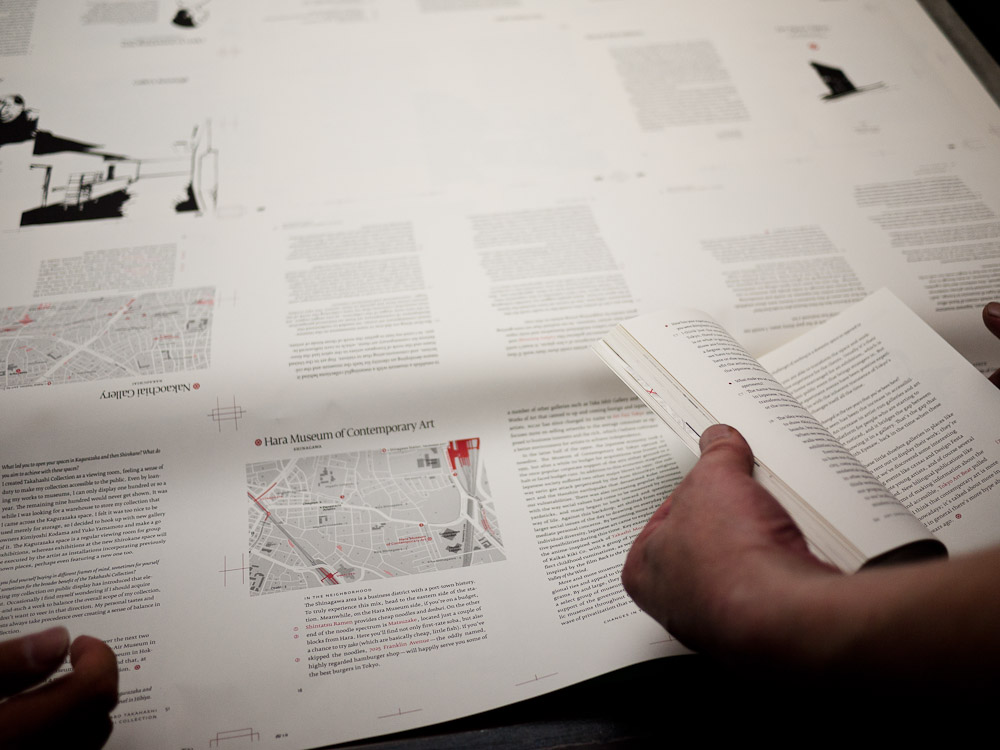

Ink density is our concern today. I don’t know the name of the technician, but he’s determined to get the density just right for the body text and illustrations. Kohiyama-san, the print coordinator, is by my side and for the first time I realize just how much he understands the aesthetic we’re after. “The back looks good but you need to open up the front a bit more,” he barks over the din of the printing machines. I agree and keep my mouth shut. The technician fingers the ink saturation levels on the giant panel and sends a new wave of test prints through the system.

The trick is to throttle the black. I was drawn to the work of our illustrator Nobumasa Takahashi for a number of reasons. I love thick, contrasty ink drawings — his specialty. But I also love his tenacity and devotion to the process. He devotes as much time to mixing his ink and drying it in just the right way as he does to drawing. By commingling inkstone and water at just the right density and drying them at just the right speed with just the right amount of heat, he’s able to pull out nuances that other illustrators overlook. He’s able to create illusions of flecks of metal and imbue his work with a depth often lost in this style of illustration.

We’re looking to protect that depth.

A testing rhythm emerges. New print checked against previous print and then checked once again against the first edition of the book. We tread lightly in tiny increments — to bring out too much detail in the illustrations will steal density from the body text and maps. Printing of this type is a balancing act of aesthetics and pragmatism. Thankfully, we're in very capable hands.

Pledge Analysis

People engage things: a) when they’re brand new, or b) when they're nearing a deadline. We lose interest in that middle space. Considering this, I was tempted to make the pledge round for AST only three weeks long. One week for the initial push, one as a ‘buffer’ week, and then one for the final push. The buffer would simply act as a psychological pause between us screaming “IT’S NEW!!!” and “IT’S ALMOST FINISHED!!!”

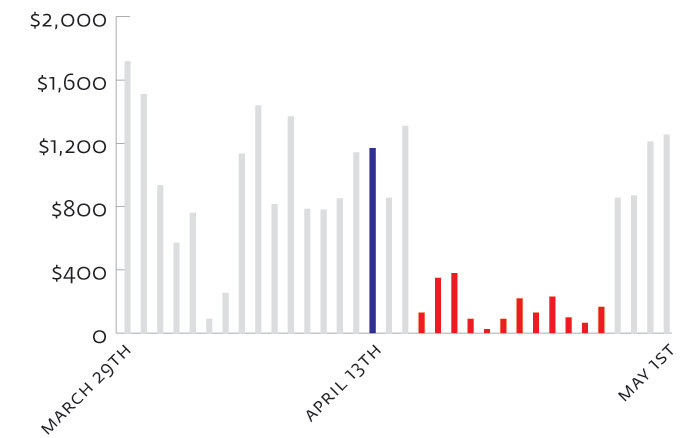

In the end we set the pledge round to five weeks, but looking back, I think four would have been enough. While the additional time allowed us wiggle room for reaching out to blogs and web magazines (which may take several days or weeks to publish a post), there’s an obvious 12-day dead period (shown in red). Doing it again, I would aim for better coverage in online media during that week.

Here's a graph of pledge amounts by day for the duration of the campaign:

Kickstarter daily pledge totals

Our top grossing day was our first day, March 29th, with $1,720.00 in pledges. Our worst day was April 20th at $25.00. The average daily pledge total was $695.88.

We hit our financing goal on April 13th, just 16 days into the campaign. The campaign then slid into the boring neither new nor about to finish zone. These combined to result in the twelve day pledge dead-zone in the weeks leading up to the end of the campaign.

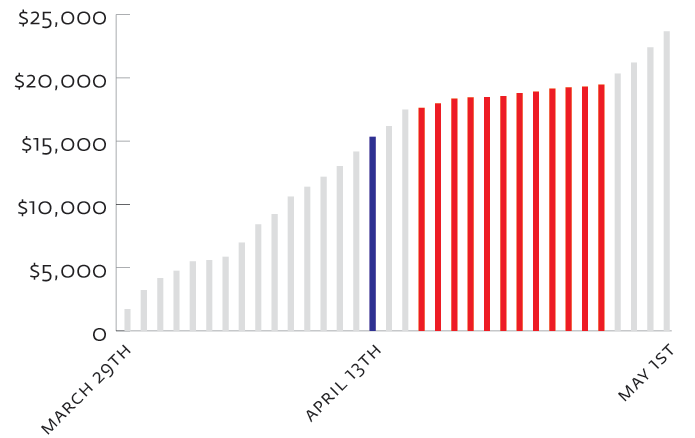

You can see we had consistent cumulative growth until we hit our funding milestone:

Kickstarter Cumulative Pledge Amounts

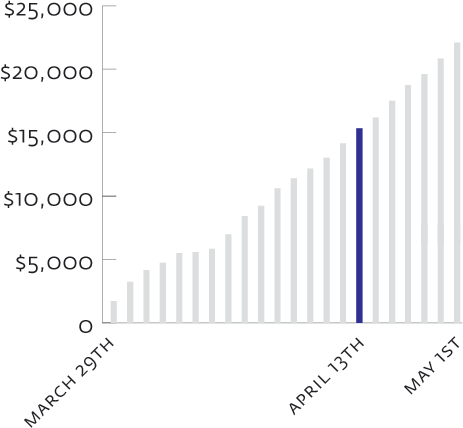

In fact, if you cut out that dead zone and readjust the totals, we get:

Kickstarter Cumulative Pledge Amounts:

12 Day Dead Zone Removed, Totals Adjusted

During that 12 day lull, we received only $1976.00 in pledges at an average of about $165 a day. This was far below the daily average of almost $700 (or what would have been almost $1000 a day without the dead zone).

Why care? Isn't $2,000 still $2,000. Sure, but if you can't push forward on your project until you have the money, then efficiency also has worth. The more efficient your campaign is, the easier it is to maintain a high level of interest. Linger too long and you risk waning enthusiasm. In other words — that $2,000 could have been more efficiently baked into a shorter campaign.

Promotion Strategy and Action

Ashley Rawlings, Art Space Tokyo's editor and co-author, and I promoted the Kickstarter project using three primary resources:

- Twitter and Facebook

- Our vast personal mailing lists of contacts in the art and design world

- Online media: a number of top art and design blogs and magazines

Our promotional strategy went something like this:

- A steady rhythm of informative Twitter and Facebook updates

- Mailing list blitzes at the start and the end of the fundraising period

- A gentle progress update to the mailing list mid-way — a great chance to highlight any particularly impressive media coverage

- Seeking relevant online media postings about the project throughout the timeline

The timing for Kickstarting this project couldn’t have been better. A lot of folks around the world had suddenly become interested in what some guy in Tokyo had to say about the future of books. With all these new ears turned in my direction (mainly on Twitter) I had a fresh, captive audience that was likely to be interested in the Art Space Tokyo project. I tried to keep any Tweets about the project relevant and to a minimum. The point wasn’t to saturate my Twitter stream with AST updates (and I’m sorry if it felt like that), but rather to gently remind folks that the project had momentum and we were still looking for pledges.

You can review the tweet/retweet timeline for the entire campaign over on Topsy.[4]

Mailing Lists

We took advantage of the vast contact lists we had built up while working in the design and art worlds over the past six years. Days on which the mailing list emails were sent, the amount pledged the day before, the day of the campaign and the day following are listed below:

| Date | Campaign | Previous Day $ | Day of $ | Following Day $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 6 | It's New! [a] | $1,135.00 | $1,440.00 | $815.00 |

| April 8 | It's New! [b] | $815.00 | $1,370.00 | $785.00 |

| April 15 | Midway Update | $855.00 | $1,310.00 | $130.00 |

| April 30 | Three days left! | $870.00 | $1,210.00 | $1,255.00 |

As you can clearly see, each mailing (1,000 recipients on April 6, 1,000 on April 8, 2,000 on the 15th, and 2,000 on the 30th) resulted in a significant jump in sales. Curious as to what we sent? Here's the mails:

- April 6/8: It's New! [a/b]

- April 15: Midway update

- April 30: Three days left!

Blogs / Online Media

My strategy for promoting projects is simple: I find a number of key, influential sites with topics that overlap with what I’m looking to promote. I then write emails specific to those blogs, magazines and newspapers, highlighting the aspects of the project I think they’d be most interested in. Oftentimes, I’m writing to blogs that I’ve been reading for years, so for me, referencing older posts of theirs and personalizing these emails is trivial, and fun.

Whatever you do, don't send scattershot emails to media outlets. Be thoughtful. The goal is to appeal to editors and public voices of communities that may have an interest in your work, not spam every big-name blog. A single post from the right blog is 1000% more useful than ten posts from high-traffic but off-topic blogs. You want engaged users, not just eyeballs!

For the Kickstarter Art Space Tokyo project Ashley and I were able to drum up coverage from more than a dozen relevant publications, including the following:

| Date | Source | Community |

|---|---|---|

| March 30 | 37Signals, SvN | Entrepreneurs |

| March 31 | Spoon & Tamago | Design, Japan |

| April 1 | Kickstarter Tweet | Kickstarter |

| April 1 | Hypebeast | Design |

| April 5 | Viewers Like You | Design |

| April 9 | Superfuture | Design |

| April 9 | Complex | Design |

| April 9 | Street Giant | Design |

| April 10 | Notcot | Design, Art |

| April 11 | Subtraction | Design |

| April 13 | We Jet Set | Design, Travel |

| April 13 | Limited Hype | Design |

| April 14 | Jean Snow | Tokyo, Design, Art |

| April 16 | PSFK | Art, Design |

| April 17 | Nonaca | Art, Tokyo |

As you can see, our campaign ended up quite top heavy — it would have been great to have gotten more coverage in the post-April 17th range. Looking back we should have started prepping the media earlier (we began almost simultaneously with the Kickstarter campaign) and tried to negotiate publication dates.

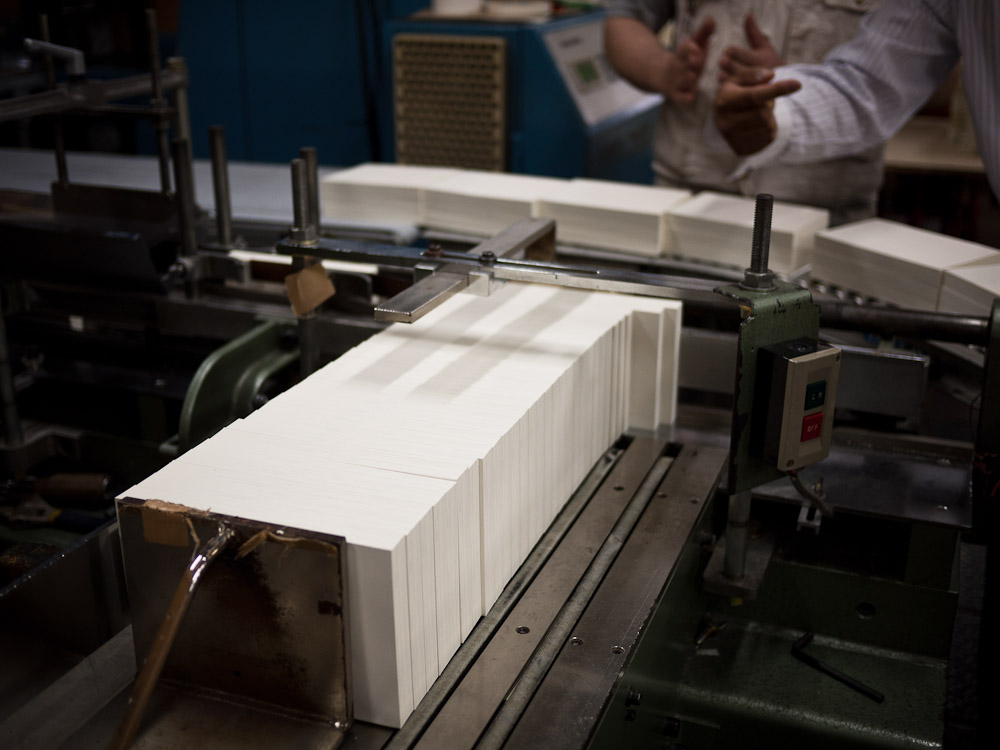

Bindery Business

The journey from InDesign file to actual book ends at the bindery. Our bindery is located in Hongo in the old printing ward of Tokyo, just northwest of the Imperial Palace. This district of miniature warehouses tucked between homes and apartments must have once been much grander than it is now. Vacancy signs and warehouses converted to non-print related uses abound. It feels like an industry morgue. It’s an area that clearly has an expiration date.

It's May and today is the first truly hot day of the year. Sweating, Kohiyama-san and I snake past a few houses down a skinny side street and arrive at our destination guided by the rhythmic clunk-clunk-clunk of the cutting and binding machines.

We step out of the blazing sun into the cool darkness of the bindery. Almost every machine has two people manning it and Kohiyama-san — my constant companion and narrator through all of this — leans over to me and whispers about how rare that is. “You’re lucky to have one guy on two machines at these places.”

There’s a pride in perfection of output at all of these print shops. True to the stereotype of Japanese excellence in craft, these printers and binders are all master craftsmen. I'm moved by the attention and care they're giving a small project like Art Space Tokyo.

At every step each book is checked and double checked. Processes you'd expect to be fully automated have just a touch of human intervention — process editors, if you will — guiding the partially made books safely to the next stage.

Standing at the end of the production line I watch the books pile up ten at a time on a giant wooden pallet. Even this process — stacking on pallets! — is given care and consideration, with every other book placed in the opposite direction to ensure even pressure on the binding when the stack gets tall.

I watch as the number of books grow. The pallet is now three-quarters full, and I turn to each of the crew, thank them, take one final photograph and then — thinking to myself how grateful we were to have had both the Kickstarter and Japanese printing community support to make this happen — walk back out into the scorching sun.

Doing it Differently

Our biggest mistake was that we set our financial goal too low. It’s inevitable that a Kickstarter project becomes less exciting and loses its ‘gambling’ element when the financial goal is met and there's still time on the clock (just look at our funding graphs above for empirical evidence!). An ideal situation for any Kickstarter project is to define a financial goal that is high enough to just be met within the allotted time.

When we started out, $15,000 felt like a stretch. It works out to $500 — or nine books — a day in pledges. Not ransom money but still nothing to sneeze at. $15,000 was the minimum required to produce enough books to make the effort worthwhile. The idea was that every dollar above that minimum would go to expanding the project's scope. In raising $24,000 we were able to increase our print output considerably and I’m happy to report the project now has very strong legs.

I hope it doesn't sound greedy to say you should set your goals high. Remember, maximizing the financial goal means simultaneously maximizing the community engagement. You're not just getting more money but building a stronger community.

What were we able to accomplish with $24,000? We've managed to nearly double the clothbound, silkscreened hardcover print run of Art Space Tokyo, update the book's maps, restaurant and cafe suggestions, perform a thorough re-edit, launch PRE/POST, setup fulfillment and shipping in Tokyo, ship out over 300 books, support one of the most important art book shops in Tokyo with a launch event and get this essay out. All in three months. I think that's pretty damn good.

This essay marks the closing of the first chapter in this experiment. Moving forward, all efforts will be focused on building the digital edition of the book. Sharing, of course, what we learn along the way.

Aiming for $1,000,000

In summary:

- $24,000 in a month

- Kickstarter = escrow made easy & sexy

- Think in terms of micro-seed capital not one-off money

- Fewer Tiers = better

- People want to pledge $25 and up!

- Plan media coverage to avoid dead zones

- Promote smart: Focus on high quality community coverage

- Be brave: Push your pledge goals to the edge

A mere five years ago it would have been unthinkable to use social media to drum up $24,000 for the republication of a book. We accomplished not only that, but have been able to price the book sustainably, launch a publishing think tank, sell direct to our audience and buck traditional distribution channels. We are, undeniably, in an era shaping the future of publishing — how it happens, with whom it happens, and on what terms it happens.

My hope is this article helps at least fifty other creators accomplish something similar. Fifty creators achieving our meager level of success means unlocking over $1,000,000 in money to flow into creative and socially important projects. All the successful projects on Kickstarter are indisputable proof that this is possible. Let us know what you create. We're eager to hear.

Notes

- Or a little over $21,000 post-Amazon (3%) and Kickstarter (5%) fees ↩

- Books in the Age of the iPad — Craig Mod, PRE/POST, March, 2010 ↩

- Definite Content, Craig Mod, March 2010 ↩

- Topsy's archive of AST related campaign Tweets. ↩

About the author and essay

About the author

Craig Mod is a writer, designer, publisher and developer concerned with the future of publishing & storytelling.

He is the founder of publishing think tank PRE/POST. He is co-author, designer and publisher of Art Space Tokyo. He is also co-founding editor and engineer behind TPUTH.com, co-founder and developer of the storytelling project Hitotoki, and frequent collaborator with Information Architects, Japan. He's lived in Tokyo for almost a decade and speaks frequently on the future of books and media. He is the worst speller you will ever meet.

An extensive collection of images of books he's designed is available here.

Where this was written

All around Tokyo — in the tatami house, Gaienmae Starbucks, Dragonfly Café, Orinoco offices, Respekt, Starbucks & that weird surfer cafe in Hiroo; down the Izu peninsula in Atagawa, on the Shinkansen in Kanagawa, on the Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka, in the mountains of Wakayama, on an airplane flying above the pacific, at Stanford D-School, Coupa Coffee, Palo Alto, Cardinal Hotel, the Tea Room (where I'm typing these very words) and a whole host of other places I can't possibly remember.

Thanks

Massive thanks to Ashley Rawlings for his excellent editorial suggestions and insights. This monster is eminently more palatable thanks to his efforts. And Liz Danzico for her invaluable time in helping me properly frame all the above.

Get the book!